Alaska's oil crossroads: lucrative OCS prize and TAPS pipeline fuse

Steven R. Kopits

Douglas-Westwood LLC

New York City

Alaska's oil business faces an uncertain future.

Alaskan production, principally from giant Prudhoe Bay field and shipped south through the trans-Alaska pipeline, began in 1977 and peaked in 1988 at just under 2 million b/d (Fig. 1). It has been in decline in all but 2 years ever since, with production falling by half every 12 years. For 2013, production is expected at only 510,000 b/d.

From the perspective of the Alaska state government, this should matter. Oil revenue represents some 90% of the state's budget, eliminating the need for state income and sales taxes while affording Alaskans such luxuries as the nation's lowest gasoline taxes. However, declining production had been until recently masked by surging oil prices.

Changing economic fortunes

Whereas Alaskan oil production (valued at the Brent blend price) was worth about $10 billion in 2003, by 2008 a smaller volume of production was worth as much as $23 billion at global prices (although somewhat less at the price regimes pertaining in Alaska).

Even as production was flagging, oil revenues continued to balloon. This in turn encouraged the administration of then Gov. Sarah Palin to institute in 2007 a new tax regime known as ACES (Alaska's Clear and Equitable Share), which succeeded in bringing in about $5 billion more in the next 4 years than would have been expected under the previous law.

Alas, the ACES regime also had the effect of stalling oil industry investment in Alaska. Even as surging oil prices were stimulating investment in deep water and shale oil, Alaska's business lagged. Partly as a result, the state's oil production decline rate accelerated.

In the last 3 years, observed decline rates averaged 6.8%, up from 4.4% in the previous decade. While this was acceptable when oil prices were rising, it became problematic as oil prices stalled after 2011. ACES, which had looked like a winning proposition before the recession, now appeared a liability. It threatened to kill Alaska's golden goose of oil revenues.

And what a golden goose it is. The State of Alaska received a total of $9.2 billion in oil revenue in 2012, about 56% of the oil and gas sector's total revenue in Alaska that year. Furthermore, this sum is spent on Alaska's small population of only 725,000. As a result, the oil business provides more than $12,000 in state spending per person per year, or about $50,000 for a family of four.

Alaska has, unsurprisingly, the highest level of state spending per capita in the nation. Thus, the debate about declining oil production and revenues for Alaska is not a peripheral issue; it is an existential debate about the future of Alaska.

Faced with falling production, confiscatory tax rates, and hostility from the oil industry, the administration of the current governor, Sean Parnell, in 2012 reformed the oil law, reducing tax rates to 35% from the theoretical maximum of 75% under ACES.

The new tax regime, known as Senate Bill 21 (or SB 21), was passed in April 2013. BP and ConocoPhillips promptly announced new programs of $1 billion and the intent to evaluate up to $3 billion of new projects in the Greater Prudhoe Bay area.

It is hoped that lower tax rates will stimulate increased oil production beyond just the promises of investment, and indeed, activity levels appear to be rising. Permits to use the Dalton Highway, a 300-mile gravel road leading to the North Slope, have increased by 30% in recent months. The question is whether this will translate into increased production volumes.

Not all Alaskans are happy with the lowered tax rates, and various groups have gathered the signatures necessary for a referendum to restore the higher ACES brackets. At issue is not the desirability of producing oil. It is all about splitting up the oil revenue pie. Alaskans are well aware that any profits earned by the oil companies will go to shareholders outside Alaska, principally to pension and investment funds in the Lower 48 states, as well as to the foreign shareholders of companies like Shell and BP.

Therefore, whatever profits Alaskans do not keep will flow out of the state. This would be no tragedy, if Alaskans also believed that lowered tax rates would stimulate oil production, but they harbor doubts about whether reduced rates will actually lead to materially higher production. In this, the oil majors themselves are less than sanguine.

Uncertain oil production upside

Alaska's unique features dictate why this is so.

Unlike Texas, for example, Alaska is a much more difficult place to extract oil. The federal and state governments (including native lands) own 59% and 40% of the state, respectively. Private landowners own less than 2% of all land.

As a result, access to virtually all prospective acreage involves obtaining state or federal permits, and this can be enormously time consuming, if it is allowed at all. For example, ConocoPhillips is still in the process of securing all required permits for a satellite development near the company's Alpine field on the North Slope 8 years after it first initiated the permitting process.

Climate and geography are similarly challenging in Alaska. On the North Slope, exploratory work must be conducted in winter (because the ground is wet, spongy tundra in the summer, making it impassable for most vehicles). Therefore, field delineation must occur during the winter, with access provided by ice roads. These in turn cost $1 million/mile to construct, only to melt without a trace the following spring. Whereas delineating a field in Texas might require a pick-up truck and a few months, in Alaska it typically requires 3 years, including annual road building, as well as the costs of operating in extreme temperatures without meaningful logistics or infrastructure support.

For this reason, activity in Alaska is dominated by just a few major companies: BP, ConocoPhillips, Shell, and ExxonMobil. Only these have the technical sophistication and deep pockets necessary to match the regulatory and climate challenges of the state.

This is not to say that independents are entirely absent. Pioneer Natural Resources, Apache, and Anadarko, to name a few, have interests in Alaska. Pioneer, for example, invested about $1 billion over time in its Oooguruk field, which is currently producing around 4,000 b/d. But it is cheaper, easier, and quicker to obtain such production from shale plays in the Bakken or Texas, and the activity levels of independents therefore are relatively muted in Alaska.

At the same time, the majors themselves do not see more than a few thousand barrels per year in upside. Forty thousand barrels per year—enough to offset decline rates—is thought ambitious, and the industry regards 20,000 b/d of new production each year as a more realistic target.

Moreover, the focus will remain on light oil even as billions of barrels of heavy and viscous oil lie stranded on the North Slope. If this heavy oil could be processed at acceptable cost, the volumes could be formidable, and BP has, in fact, examined the issue. Unfortunately, the company's analysis concluded that processing heavy oil, while technically feasible, was not economically viable. Consequently, BP will continue to focus on light crude, and the heavy oil will remain in place.

Taken as a whole, therefore, the outlook for Alaskan onshore production is guarded at best and uninspiring at worst. And Alaskan voters have some sense of this, which is the driver of the referendum on raising oil taxes. The number of eggs the golden goose may lay in the future has come into question. And if there will be no more eggs, then the fate of the goose itself is on the table. Alaskans are beginning to think they should get all they can, while they can, and reconcile themselves to a day when Alaska will no longer be an oil producer.

Beaufort-Chukchi oil ambitions

But the future may not be so dark: Alaska may have a few more eggs to give, and they are huge.

One of the key lessons of Alaska is that scale matters. Prudhoe Bay worked because it was a monster, large enough to justify working on the frigid, dark, and inaccessible shores of the Arctic Ocean; large enough to justify a 789-mile pipeline; and large enough to justify the massive investment to bring it all together.

New projects onshore lack this scale, and they struggle as a result. But as it turns out, Alaska may yet have two unexploited monster opportunities—offshore, on the Alaskan Outer Continental Shelf (OCS).

The Chukchi and Beaufort seas lie north of Alaska. The Beaufort is directly north from Prudhoe Bay, and the Chukchi lies to the northwest, curving around toward Russia. Both of these regions are thought to contain oil, and indeed, a lot of oil, as much as 27 billion bbl of potential resources.

The potential of these regions was known to the operators, as Shell and others has drilled wells in the OCS back the 1980s and 1990s. Although interest waned during the low oil price years of the late 1980s and 1990s, operators began to reconsider the plays as oil prices began to rise a decade ago. This in turn led to lease auctions from 2005, with Shell winning the lion's share of both the Beaufort (2005) and Chukchi leases (2008) for $2.2 billion (Fig. 2). The company perhaps had the advantage of having drilled the plays decades earlier and had an inkling of what might be there.

Nevertheless, Shell's move at that time could only be described as visionary. In 2005, the global oil supply was beginning to lose its resilience, but there was no clear sign yet of the high oil prices that have become commonplace. At a time when consultants such as IHS CERA were proclaiming that world oil production capacity would be 100 million b/d by 2010 (it is barely above 90 million b/d in 2013), Shell went all-in on thehigh-cost Alaskan OCS.

The scale and ambition of Shell's proposed venture is breathtaking. In the Beaufort, Shell sees seven smaller fields, each to be mounted with a fixed platform. These will be tied back to Prudhoe Bay with some 235 miles of offshore pipeline. Shell hopes to produce 600,000 b/d at peak from these platforms, about 100,000 b/d/platform. Thus, Beaufort output alone would equal literally half of US Gulf of Mexico production today.

Plans for the Chukchi are even more ambitious. The play comprises four large fields requiring 680 miles of onshore and offshore pipe. Shell hopes to produce 1.2 million b/d at peak—almost as much as Gulf of Mexico production today.

The Chukchi sites would likely be developed using gravity-based platforms of the sort found in Atlantic Canada's Hibernia field. These would be towed to the site and lowered to the seabed. Development drilling would be performed through the platform and involve 30-40 wells with long laterals. Such platforms have a maximum capacity of 250,000-300,000 b/d. Thus, four or five of these would be enough, in principle, to develop the Chukchi.

All of Shell's OCS sites are in shallow water (140 ft) and represent relatively low pressure wells, about 3,000 psi according to media reports. This is a far cry from Gulf of Mexico wells where 10,000+ psi wells are common and the industry is testing the 20,000 psi limit.

The Burger prospect, located 70 miles northwest off the Alaskan coast in the Chukchi Sea, is considered the most promising play in Shell's Alaskan portfolio. In 2012, after a number of delays related to ice encroachment and problems with completing inspections of its containment system, Shell was granted the necessary permits and drilled a "top hole" (half depth) well at Burger. After 5 years and nearly $5 billion dollars invested, Shell had half a well and was yet to encounter hydrocarbon-bearing layers. It was a disappointing outcome.

And the trouble did not stop there. As it was being towed to Seattle for maintenance, Kulluk, the drilling rig Shell had intended for use in the Beaufort, ran aground off Sitkalidak Island in the Gulf of Alaska, on the last day of December 2012 (Fig. 3). With that, Shell concluded a frustrating year.

Shell had finally started drilling but was victimized by mishaps left and right. With the Kulluk grounding, Shell would choose to sit out the 2013 drilling season. Shell's troubles did not go unnoticed: Both ConocoPhillips and Statoil decided to defer their OCS programs pending greater clarity on Shell's situation.

The 2013 economic pinch

Meanwhile, back in Houston, the economics of the oil business were coming under pressure. Exploration and production costs had been rising inexorably at the pace of 11%/year, but oil prices peaked in April 2011 with the Arab Spring and had been trending down since.

The operators were finding themselves in an uncomfortable wedge, with increased costs not recognized in selling prices. These pressures culminated for the oil majors in a disastrous 2013 second quarter.

ExxonMobil saw profits drop by 57% for the quarter and subsequently announced it would discontinue its share buyback program. Statoil announced it was "putting the brake" on new projects. Across the industry, capital intensive projects were being "pushed to the right" as current capital budgets were cannibalized to pay for cost overruns from previous initiatives.

For its part, Shell posted numbers which equity analysts at Bernstein Research described as "one of the worst set of Shell results that we can remember." In response, Shell CEO Peter Voser declared that the company was dropping production targets to focus on cash flow growth targets with "a sharper focus on fewer projects."

For Alaska, this has a specific interpretation. Whereas the oil majors had previously committed to increasing production, the reality of rising costs and flat revenues means that the oil majors will do what is necessary to create profits, even at the expense of becoming smaller companies.

Shell has repeatedly reaffirmed its desire and commitment to Alaska. But the sobering truth is that Shell now reserves the right to abandon any project that fails to improve cash flow, and Alaska will clearly not generate cash flow for Shell for the next 15 years or so. Indeed, it will consume a prodigious amount of cash, particularly in the 5 years preceding first oil.

Shell's OCS development costs are likely to be impressive. At present, a flowing rate of 1 million b/d of new crude oil production has a capital cost of $100 billion, using an industry rule of thumb. If we allow Shell intends to produce 1.8 million b/d at peak from the Alaskan OCS, the associated capital cost would be $180 billion.

Perhaps the cost will be lower. Unlike the Gulf of Mexico, the OCS wells are low pressure and in shallow water. The fields are also large, lowering unit costs. But still, the logistics and permitting in Alaska are forbidding. Could Alaska come in at half the cost of a comparable Gulf of Mexico project? Perhaps, but even that would represent a development cost of $100 billion for the OCS.

Of course, not all investment would precede oil production. Nevertheless, according to industry experts, first oil is likely to cost $50 billion, including leases, drilling, pipelines, and platforms. Such an investment would fund a 300,000 b/d platform, which would likely bring Shell only to breakeven. Additional platforms, leveraging off of existing infrastructure and project development, would bring profits thereafter.

This suggests that neither Shell's incoming CEO nor his successor is likely to see Alaska increasing the company's cash flow during their tenure. Rather, Alaska will be a cash drain.

When operators had the luxury of focusing on production growth and taking the long view, this might not have mattered. In today's world, it very well might. No matter what the lure of the treasures of Alaska's OCS, if the profits are not there, Shell may abandon the initiative, even if it means the company will shrink in the long run as a result.

The timeline has also shifted. First oil was expected for the early 2020s, but given delays and additional regulatory requirements, after 2025 seems more likely, and for some projects as late as 2030. But will it arrive in time?

All North Slope oil production, including that of the OCS, must flow through the 789-mile, 48-in. Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) connecting Prudhoe Bay to Alaska's southern port of Valdez. Designed with 2.1 million b/d of capacity, the TAPS, as the pipeline is called, will operate under 25% of rated capacity for the first time in its history in 2013. And this in turn is causing a variety of operational problems.

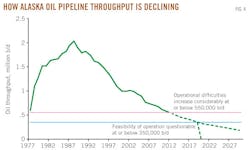

Whereas crude traversed the pipeline in only 4 days 20 years ago, now it requires 20 days. Maintenance and flow assurance are ever greater issues. No one is sure when the TAPS will lose viability, but there are doubts the pipeline will remain viable below 300,000 b/d (Fig. 4).

As TAPS is the only route to market, Shell must factor into its plans the likelihood that the TAPS will remain in operation when it reaches a point of being able to refill the pipe. At recent decline rates, the TAPS will reach the 300,000-b/d threshold by 2020.

Even if the hoped for 4% decline rate is attained, the TAPS will reach the viability threshold in 2024, just about the time that Shell begins OCS production.

The August 2014 referendum matters for just this reason. If Alaskans vote to reinstate the ACES tax rate, then incremental upstream investment is likely to be minimal, decline rate high, and the TAPS may lose its viability by 2020. Shell then would have to consider whether it wants to take on responsibility for the pipeline preemptively (assuming the current owners of the pipeline would assent).

But should it do this when Alaskans themselves have voted against the future of their industry?

Lucrative but fateful OCS prize

For Shell, the Alaskan OCS would be an unmatched prize.

There is no other play like it. It would propel Shell past its peers for a decade or more. It could be unimaginably lucrative, as well as a feat for the ages. However, balanced against this is the sheer scale of the challenge, the risks and capital invested, a state and federal government seemingly more intent on obstructing or killing the project than helping it succeed, and perhaps most importantly, the long time needed to bring the project on line.

At the end of the day, the fate of Alaska hangs in the balance. If Shell succeeds in the OCS, the pipeline will be refilled and Alaska will enjoy the benefits of oil wealth until the middle of the century. If Shell withdraws, the days of the TAPS are numbered.

If throughput drops below 300,000 b/d and the pipeline has to shut down, 1 billion bbl of proved reserves–which could otherwise be produced economically–may be stranded underground. Were the TAPS to close, the Alaskan economy would be forced to adjust literally within weeks. The sobering truth is that Alaska is one bad board meeting at Shell away from seeing the end of its oil age.

Given the stakes, one would think that the issue would be more high profile. Shell might be expected to trumpet its plan as critical to the Alaskan economy, as the key source of incremental US oil in the postshale age (because the US will be years past anticipated peak shale production by the time the OCS comes on line), and as the single most important economic initiative in North America. All of these are true. Nevertheless, even within the oil industry, few know that Shell's plans in the OCS could exceed the entire production of the Gulf of Mexico.

And we would expect no less that the State of Alaska would champion its cause in the Lower 48 states to create understanding about the stakes and the need for government and public support. But oddly, none of this has happened.

Alaska, largely invisible in the Lower 48, has not made its case. No one has any idea of how important oil revenues are to the government of Alaska, and the long-term risk to the viability of the TAPS is unremarked. It is a strange situation.

Perhaps the parties will become more vocal or the story better covered by the media. But one thing is clear: Shell and Alaska will share a fate on Alaska's Outer Continental Shelf. They succeed or fail together, and the stakes are extraordinarily high.

The author

Steven Kopits ([email protected]) is managing director of Douglas-Westwood LLC (USA) in New York City. Since joining the firm in 2008, he had led dozens of projects on various oil field technology and service projects. He has a background in strategic management consulting and investment banking, having assisted more than 100 companies in market analysis, business planning, and related financial modeling throughout a range of industries including energy, manufacturing, power, and maritime shipping. He writes frequently on issues related to energy and the economy.