Iraqi's ambitious production aims supported by progress in oil fields

Stan Harbison

Ben Montalbano

Lucian Pugliaresi

Energy Policy Research Foundation Inc.

Washington, DC

Iraq's 2009 announcement that it planned to increase its oil production by 10 million b/d attracted global attention but received broad dismissal by oil observers. Iraq had not established a firm national political authority in the wake of the overthrow of Saddam Hussein and the long and violent period of US military occupation. Security problems appeared to make progress difficult. Iraq had proposed grand oil production plans at least five times in the past 30 years but never delivered visible results.

It was only in mid-2010 that the International Energy Agency included a longer-term forecast reflecting Iraqi production gains—an increase of 1 million b/d over 5 years, making Iraq an important but not central factor in the future oil market. This continues to be the consensus in the oil market.

Work in Iraq has proceeded on a very large scale, in most cases on or near the schedule set in detailed contracts let to international oil companies. The companies have invested over $5 billion within the past year, a meaningful portion of it unrecoverable bonuses. Announcements from operators of three major field-development projects—BP, ExxonMobil, and Eni—in the past few months confirmed that they had achieved or exceeded contractual targets. Production increases under these contracts have combined to boost Iraqi exports by 300,000 b/d (Fig. 1).

Iraqi ambitions

Iraq's oil reserves may rival those of Saudi Arabia. Iraqi geologists and engineers, citing field data and conservative estimates of recovery from oil in place, place the number at well over 200 billion bbl.

Yet Iraq ranks 12th in the world in oil production capacity and recently has produced about 2.4 million b/d, about 25% of Saudi output. Its cumulative production is just 25% that of Saudi Arabia's. Average annual output peaked in 1979 at 3.5 million b/d and has never again exceeded 2.8 million b/d, despite very low costs of development and production. Iraq's oil costs were estimated to be the lowest in the world in a 1995 IEA report.

For 30 years following Iraq's ill-fated 1980 invasion of Iran, the Iraqi oil industry concentrated on rebuilding war-damaged infrastructure and attempting to maintain production levels rather than raise them. By 2010, 85% of Iraq's cumulative production had come from just two fields. After 1980, funding was never adequate. Access to foreign equipment and contemporary technology was cut off. Iraq's annual average production was 1.7 million b/d between 1980 and 2009 and reached 2.5 million b/d or greater in only 5 of those 30 years.

Immediately following the US overthrow of Saddam Hussein's government in 2003, Iraq's oil leadership developed plans to invite capable foreign oil companies to lead a rebuilding of the industry. But the plans were stymied by governmental gridlock and the deep suspicions of the broader Iraqi public toward foreign control of Iraqi oil. By 2008, visions of an industry renaissance had been replaced by several failed attempts by the Ministry of Oil to bring in foreign companies for 1-2 year service contracts.

The auctions

The establishment of the government of Nouri al-Maliki enabled several of Iraq's most senior oil professionals to write an oil law by early 2007 that could serve as a legal basis for oil development. But Kurdish opposition, given a veto by the structure of the Iraqi constitution, blocked its passage.

After 2 full years in this stalemate, Iraq's central government found a way to effectively sidestep the Kurdish veto. It linked a 1989 Saddam-era law to the 2005 constitution, which provided a tenuous but successful way to move forward on a grand plan to invite large foreign oil companies to lead development of Iraq's giant fields. The government implemented two auctions allowing foreign oil companies to assume technical service contracts to develop the country's largest oil fields.

The auctions were seen to be politically risky and unlikely to succeed. The terms were very tough from the bidding oil company point of view. Terms had to be tough to accommodate the deep political aversion to foreign control of Iraqi oil. International companies demonstrated their displeasure by offering bids in the first round for producing fields that were generally far lower than the government's minimum thresholds. The only successful bid, made by a consortium of BP and China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC), rescued the government's initiative. It opened the door to later acceptance of government terms on the two other giant producing fields on offer.

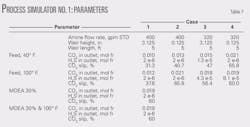

This led to an intense competition for the offered nonproducing fields in the second round. By mid-December, the government had in hand the successful bids on contracts to operate 10 fields (Table 1).

The contracts

The oil ministry offered rights to develop Iraqi fields on the basis of contracts that were tough enough to diffuse nationalist objections yet allowed companies to achieve acceptable returns. Less than 1% of oil revenues after recovery of capital costs accrue to the operating companies as profit. But provisions for very rapid reimbursement of nearly all capital costs—for field investment, production expenses, and other costs such as security and training—create the prospect for returns of roughly 15%. BP and ExxonMobil have said they are confident of achieving returns of close to 20%.

The absolute size of the profits is small in the portfolios of the large companies involved, but that is offset by limited exposure of capital to risks at any one time. Importantly, the contracts contain no oil price risk to the companies. The contracts, detailed and thorough, mandate a complex bureaucratic structure that assures meaningful participation in operating decisions by Iraqi oil professionals and politicians representing interests in areas around the fields.

Iraq's goals do not match the efficiency-focused approach that major oil companies take toward large projects. In a competitive environment, the lowest-cost producers prevail. But Iraq's national interests demand that revenue increases be large and occur as quickly as possible. The country faces an economic challenge similar to those faced by Germany and Japan after World War II. Because rebuilding and expanding the Iraqi economy will require large and reliable funding, the contracts are geared to achieving ambitious production targets on time.

The emphasis on volume and speed separates Iraq's oil industry from those of the large Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries producers, which seek above all to minimize the long-term depletion of oil reserves. Core OPEC production has changed little from levels of the late 1970s. Iraq has the potential to break this mold. Its reserves-to-production ratio will drop from well over 100 to 30 if it approaches its production targets. Envisioning the production of tens of billions of barrels of reserves, the oil ministry is developing long-term plans to accelerate an exploration effort to replace produced reserves. Iraq is functioning more like a western investor-owned company than as a traditional gulf oil producer.

Six of the world's eight largest international oil companies (IOCs) participate in the Iraqi projects, four as operators. Lukoil, Russia's largest oil company, and CNPC of China each operate a development. Intended or not, the result is that all five United Nations Security Council permanent members have major interests in Iraq. It also validates Iraq's potential for additional international oil company participation. Large companies that did not seek or win an interest in the projects say they retain strong interest in participating in the Iraqi oil industry.

Drilling, seismic, construction, and other types of project work are offered by a typical tender process, as is typical in the industry. Oil service companies have identified Iraq as having the potential to be one of the largest in the world. The largest companies entered Iraq quickly after the auctions were completed. Internationally prominent service companies with contracts in Iraq include Schlumberger, Halliburton, Baker Hughes, Petrofac, Weatherford, and Cameron (Table 2).

Role of technology

The introduction of contemporary technology provides enormous leverage when compared not only with current practices in the Iraqi industry but also with contract assumptions about productivity, efficiency, speed, and recovery factors. International oil company representatives with whom we talked reported that they were uniformly impressed with the quality of senior Iraqi professionals in the industry. However, they found the oil-field technology used in the fields was 3-4 decades out of date. Saddam Hussein's regime subordinated even its oil industry's interests to Iraq's foreign conflicts. Access to equipment, dialogue with oil professionals and further training outside of Iraq were largely closed

Iraqi oil fields are of very high quality with very high potential recovery rates. The ministry's proved oil reserves are based on historically established estimates of oil in place with an applied recovery factor of 35%. BP's supervising geologist has said he expects recovery rates of 65-75% in the principal reservoir of BP's field. We spoke with one of Iraq's leading petroleum engineers who reported recovery rates as high as 80% and initial flow rates of 80,000 b/d/well. The Iraqis expect estimates of oil in place to be revised upward.

Most of the companies are or will be using 3D seismic, heretofore unavailable, to assess reservoirs and target drilling. With two exceptions, Iraqi oil fields are largely undeveloped and provide much greater growth potential than their counterparts elsewhere in the gulf. The application of new technology, under elevated standards of execution, to resources as large as exist anywhere in the world creates potential for large increases in Iraqi production. A difficult industry history has delivered a reward for the current government.

Challenges and bottlenecks

Iraqi infrastructure was put in place during the 1970s, the last time capital was available. It is inadequate in scale and often in need of replacement. Much Iraqi oil infrastructure was damaged or destroyed in the wars that followed Iraq's two ill-fated invasions–of Iran in 1980 and Kuwait 10 years later. The Iraqi army itself laid enormous quantities of mines in southern Iraq, blanketing several of its oil fields as well as its port area.

Oil production growth will require a new pipeline from the Southern oil fields to the port at Basra. The current line is corroded and subject to leaks. It is running at effective capacity. Additional productive capacity at the fields must wait until a larger new pipeline is in place. Funding decisions are key. Once those are taken, work will likely move quickly.

Until more is known, pipeline capacity to the port should be considered a bottleneck to incremental production volumes.

A quick and large upgrade of Iraq's oil port facilities is needed. Work is contracted, funded, and under way. But completion of an initial increment of capacity is at least a year away until a series of four 800,000 b/d single-buoy moorings is installed. This will raise southern export capacity to nearly 5 million b/d when all the moorings are installed. A large initial umbrella contract was awarded to Foster Wheeler a year ago, and several subcontracts have been let. The pace of this work is not fully transparent at this time and will be an important near-term regulator of Iraqi production capacity.

Like their predecessors, current officials are planning large investments in major pipelines between southern and northern Iraq. There is excess export capacity of nearly 1 million b/d on the pipeline between northern Iraq and Ceyhan, Turkey, on the Mediterranean. In 2010 Turkey and Iraq signed a firm agreement to upgrade and expand this line.

Another possible outlet for Iraqi oil is the Iraqi-built and financed IPSA 2 pipeline alongside much of Saudi Arabia's large east-west trunkline with a terminal on the Red Sea. IPSA 2 has been closed since Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1990, and Saudi Arabia has shown no sign of reopening it. Iraq and Syria have discussed rebuilding the 700,000-b/d export line to Banias on the Mediterranean and have conducted physical surveys and estimates. A final commitment has not been reached, and political turmoil in Syria may make this project problematic in the near term.

Waterflood capacity

As with nearly all onshore production, the long-term maintenance of higher levels of production in Iraq rests on the capacity to conduct secondary recovery. While at least one consortium has considered using natural gas to support part of those needs, a massive water system is required.

Water will have to be moved from the gulf through a complex pipeline system to producing fields. The oil ministry tapped ExxonMobil to head up the planning. The project will be enormous; a capacity of 12 million b/d of water is foreseen. This is on par with the huge Abqaiq system in Saudi Arabia.

Costs have been estimated at over $10 billion. It is not certain how the project will be financed. Initially, a completion date for the project was set at 2013, but a more conservative timetable is likely.

Other issues

Enormous numbers of unskilled, skilled, and professional workers will be required. Operating oil companies are unlikely to provide large numbers of people from their own organizations. Locating, hiring, and training workers will be a key task and will take time and effort. The quality of Iraqi companies that act as subcontractors in providing services and doing basic tasks like construction is typically not up to international standards. Most foreign companies report difficulty finding good Iraqi workers. Where Iraqi workers are considered to be adequate, their own "infrastructure"—clothing, technical computer skills—are inadequate and will require time and training.

Most materials and equipment for the projects will be sourced outside of Iraq. Drilling companies in most cases will be able to tap their existing delivery infrastructure to procure what is needed. Incoming port capacity will be challenged but is unlikely to be a major bottleneck. Kuwait's government made provisions to allow equipment to be sent to its ports for transshipment to Iraq over land.

Thousands of landmines remain in southern Iraq. Two of the supergiant fields require considerable demining work, which is dangerous and time-consuming. Organization of the work will take time and will most likely put pressure on the timetables of a number of the field developments.

Congestion is certain. Six multibillion-barrel fields have schedules that run side by side, taxing operations and construction infrastructure that ordinarily would be straightforward. It is clear that companies will be cooperating to avoid delays. Congestion issues will become more pronounced over the next several years as development activities expand.

The limited capacity of Iraq's government bureaucracies will be a major problem. Bureaucracies everywhere are inherently rigid. An overlay of a culture of regulation in Iraq will make this a tougher problem. Bureaucrats working in Saddam Hussein's regime, particularly those at high levels, were exceedingly cautious. A small mistake carried the potential penalty of prison and torture. Small issues quickly become big ones if they are not addressed. Oil companies have been frustrated by the difficulty of obtaining entry visas for their staff. Complaints about this have been loud and repeated. The government has publicly acknowledged the problem more than once. But bureaucracy will remain a central concern.

Security, politics

Security in Iraq remains an issue, but operations in the southern fields have not experienced any severe incident. In general, security incidents in the south are low-level. Particularly in central and northern Iraq, security risks remain high.

In the south, unforeseen sectarian attacks have been at extremely low levels for 2 years or more. Normal security problems now mostly relate to kidnapping for money and to occasional resistance by local tribesman to oil company presence. Expatriates in nearly all instances require the protection of competent security firms. Good security is easily available but is expensive. There is no sign that security conditions will undermine the oil projects.

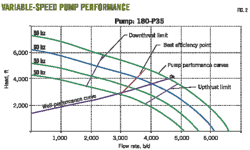

Sectarian politics, imbedded in Iraqi life, are highly important and at present seem unlikely to diminish. But to date, EPRINC has observed that the oil developments have progressed steadily despite political paralysis and sectarian conflict. The two appear to be on separate paths (Fig. 2).

Once terms of the oil contracts became publicly understood, it became clear that the Iraqi government was entitled to more than 99% of future oil revenues. There has been no serious political opposition to the framework of the oil contracts. In a country that has suffered long-term and severe financial deprivation, the prospect of sharply rising oil revenues is not something a politician wants to undermine.

Kurdistan oil

Kurdistan has enhanced a longstanding ambition for political autonomy by aggressively pursuing early exploitation of its own resources, the potential of which is very large. The region, in northern Iraq, holds oil reserves certainly approaching 10 billion bbl.

The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) has created its own oil contracts and begun its development separately from the central Iraqi government. But development of Kurdish reserves requires a frontier format because of the complex challenges of the reservoir geology.

Oil company participation depends on a contractual format that accommodates the large risk inherent in wildcat exploration. Kurdish officials established a production-sharing contract in 2007 that was acceptable to many small international exploration companies. Instances of early success and the assumption that the Kurdistan PSC format would withstand challenges by the Iraqi oil ministry attracted larger companies, which either took interests in existing leases by offering financial support or embarked on their own exploration programs. That group includes Sinopec, OMV, MOL, and, more recently, Marathon and Murphy.

Iraq's regional politics

Iran remains an important wildcard for Iraq. Ties between Shia Iraqi religious and political life and their counterparts in Iran are significant. But declining Iranian production implies an opposition of interests between the governments of Iraq and Iran. Iraq's declared interest in aggressive volume increases has the potential to moderate world oil prices—a threat to Iran.

Iran's foray into Iraqi territory a few weeks after conclusion of the oil auctions in December 2009 suggested its concern about Iraqi oil plans. Whether, how, and when Iran plans to interfere with Iraq's development in the future are not known. Iran faces ongoing declines in its oil production.

Kuwait's posture toward Iraq remains defined by the 1990 Iraqi invasion. The UN mediation following the first gulf war left Iraq heavily indebted to Kuwait. Iraqi oil sales remain subject to a 5% charge that stems from that debt. Kuwait dominates the marine entrance to Iraqi ports. Use of its waterways would be very helpful to Iraqi trade. Iraq has the capacity to supply Kuwait with at least some of the natural gas it needs for additional electric generation. Serious negotiations on any of these issues and other issues have had to wait for the resolution of Iraq's government formation.

The US and Iraqi governments have both committed to end the US military presence in Iraq at the end of 2011, in line with political opinion in both countries. For the US, a strong position in Iraq is consistent with its interest in world oil supplies and with its hostile relationship with Iran. A US withdrawal as planned will increase the vulnerability of Iraqi oil infrastructure to Sunni radical violence and any interference to oil developments that serves Iranian interests. Since Iraq's production growth will occur in the south, Iran presents the stronger potential threat to Iraqi production increases.

Acknowledgment

EPRINC has been engaged in a long-term assessment of Iraq's production potential since the announcement of the oil auctions' results in late 2009. This analysis is based on a careful look at Iraq's resources, the country's oil industry history, the state of the sector's operating institutions, the contracts that governed the proposed developments, and the potential for foreign oil and oil service companies to add value by contributing capital, technology, staff, and management capacity. Equally helpful have been discussions with Iraqi oil officials and representatives of the oil and oil service companies involved, a number of prominent security firms operating in Iraq, and US government officials.

The authors

Stan Harbison ([email protected]), vice-president, research and analysis at EPRINC, has spent nearly 30 years developing an expertise in the global petroleum industry. For 20 years he led investment decisions of a $3 billion energy portfolio at the oldest investment management company in the US, Scudder, Stevens & Clark. More recently, Harbison has served as manager-investor relations at BP, senior energy analyst at HSBC Securities, and director-global oil and gas supply demand analysis at Louis Dreyfus Energy Services.

Ben Montalbano ([email protected]) is a senior research analyst at EPRINC. He is a graduate of the University of Colorado at Boulder, where he studied economics. Montalbano joined EPRINC in January 2008 and earlier provided research support to the foundation during his college years, covering world energy markets and oil and gas production developments. He speaks Russian. In addition to his research efforts in the oil and gas market, he has worked in the information technology industry.

Lucian (Lou) Pugliaresi ([email protected]) has been president of EPRINC since February 2007 and managed the transfer of its forerunner, Petroleum Industry Research Foundation Inc. (PIRINC), from New York to Washington, DC. He served on the board of trustees of PIRINC before assuming the presidency. Since leaving government service in 1989, Pugliaresi worked as a consultant on a wide range of domestic and international petroleum issues. His government service included posts at the National Security Council at the White House; Departments of State, Energy, and the Interior; and the Environmental Protection Agency.

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com