Gas prices, other factors indicate changes in North American/shale play fiscal systems

Jerry Kepes

PFC Energy

Washington, DC

Barry Rodgers

Rodgers Oil & Gas Consulting

Edmonton

Pedro van Meurs

Van Meurs Corp.

Nassau, Bahamas

This article provides the highlights of an extensive 450-page study that sets out detailed investor favorability ratings and descriptions of 188 North American oil and gas fiscal systems in 35 jurisdictions (10 Canadian provinces and 25 US states).

A special rating of shale plays taking technical as well as fiscal factors into account is included. These ratings will assist investors in identifying profitable opportunities across North America because the study demonstrates how favorable royalty and tax terms are an important factor in making high cost and unconventional oil and gas resources attractive investment opportunities in some areas.

Governments can use these ratings to judge the effectiveness of existing and possible new fiscal systems.

The detailed analysis of fiscal terms in the study, identifying their strengths and weaknesses, provides the basis for major recommendations for substantial changes in fiscal terms in order to facilitate the continued rapid expansion of production from the huge unconventional oil and gas resources of North America and importantly enhance gas production under low gas price scenarios.

Introduction

Since 1997, when Oil & Gas Journal published the results of the rating of world fiscal terms produced by Van Meurs & Associates, the fiscal environment in the world has changed dramatically.

Many nations and areas that the Van Meurs study identified as having favorable terms have since seen significant developments, such as Brazil, the US Gulf of Mexico, Australia, Newfoundland, and deepwater Nigeria.

Fiscal systems have become more differentiated and complex. There is now a great variation in sliding scales and special features with the general aim to make a wider range of investments attractive. Significant technological developments have resulted in the introduction of special terms in some jurisdictions.

These new terms account for high cost conventional and unconventional resources, such as coalbed methane, shale oil, and shale gas, deep gas, and heavy oil in addition to the technologies utilized to develop these resources. Also, liquefied natural gas has become a widely traded commodity, and therefore links are established between the various markets that make a comprehensive fiscal gas analysis more important.

As a result, it is now appropriate to do a new worldwide rating. This exercise will rate 700 fiscal systems and is being produced jointly by Van Meurs Corp., PFC Energy, and Rodgers Oil & Gas Consulting with the assistance of Barrows Co.

Ernst & Young is providing assistance under contract with Van Meurs Corp. Five separate volumes will be produced. Vol. 1 of this study relates to the rating of fiscal terms for North American oil and gas wells and the rating of shale plays.

This article provides some of the highlights of the study. More information about the world rating study and the North American study can be found on the web site www.petrocash.com.

Vol. 1 (North America) rates and analyzes 188 oil and gas fiscal systems in 10 provinces of Canada and in 25 states of the US.

Rating methodology of oil and gas wells

The relative attractiveness of the various fiscal systems can be best measured by using the same production, costs, and prices for each system.

Standard typical oil wells are used with reserves ranging from 10,000 bbl to 1 million bbl, and typical dry gas wells with reserves ranging from 100 MMcf to 10 bcf. It is assumed that all oil and dry gas wells have the same costs and production profile for a particular reserve level. Gas prices include a differential relative to the Henry Hub price in order to net back the gas price to the field.

The base case for oil is a 100,000 bbl well at a capital and operating cost of $35/bbl. The base case for dry gas is a 100 MMcf well at a capital and operating cost of $2.90/Mcf.

It should be noted that within the various jurisdictions there are often various fiscal systems. In the US, fiscal systems in each jurisdiction depend on whether the petroleum rights are owned by the federal government, state government, or are held privately. In Canada most petroleum rights are owned by the provinces.

Various states and provinces have differentiated their fiscal terms to provide incentives for gas versus oil, horizontal wells, marginal wells, deep wells, high cost operations, and unconventional resources. Each of these fiscal systems is rated separately for oil and for gas. For this reason, in sum there are 188 fiscal systems in 35 jurisdictions in the US and Canada.

The yardsticks used to rate the various fiscal systems ("the yardsticks") are:

• Internal Rate of Return ("IRR").

• Net Present Value discounted at 10% ("NPV10").

• Profit to Investment Ratio discounted at 10% ("PIR10").

• Undiscounted Government Take ("GT0").

• 10% Discounted Government Take ("GT10").

The government take includes revenues earned by private royalty owners, Native American tribal governments, university lands, etc.; in short, everything the investor must pay to obtain and produce the lease. The government take from the production of an oil or gas well is based on the following formula:

GT = [(Government and Resource Owner Revenues) ÷

(Total Gross Revenues – Capital and Operating Expenditures)] x 100%

The government take can be determined on an undiscounted basis or a discounted basis. In this article we use real (constant) dollar values on an undiscounted and 10% discounted basis.

In addition to an individual ranking based on each of the yardsticks, the fiscal systems and shale plays were also ranked using a weighted combination of the yardsticks, in order to produce a single overall result.

Rating results for oil fiscal systems

Most jurisdictions in North America have a preference for attracting investment on an ongoing basis.

In order to attract investment, fiscal terms have to be competitive. In this framework, one would expect that the toughest fiscal terms are obtained in those areas that have the best geology and lowest costs, while the most favorable fiscal terms would be offered in areas with poor geological prospects and high costs. In general, this is indeed the case in North America.

The toughest (highest government take) fiscal systems for North American oil wells are in Louisiana, Alabama, and Texas with GT0 values over 70%. Texas and Louisiana have considerable onshore oil production.

The most attractive fiscal terms are the new discovery terms for oil in British Columbia and the horizontal well terms in Manitoba and Saskatchewan with GT0 values of less than 35%. However, the regular terms in British Columbia and in Eastern Canada and New York (on state lands) are also attractive. British Columbia, Eastern Canada, and New York have low levels of oil production and therefore, the attractive fiscal terms are consistent with the poor oil resource base in these areas.

Of the major oil producing jurisdictions the best rated systems out of 90 oil fiscal systems are:

• Rank 10: Saskatchewan horizontal oil well terms.

• Rank 16: California oil terms on federal lands.

• Rank 30: Alberta regular oil well terms (ARF 2011)

Gas fiscal systems based on dry gas wells

Currently, the relationship between costs and prices is unfavorable for dry gas wells. Assuming a Henry Hub price of $5/MMbtu and a negative gas price differential of 30¢/MMbtu, the available margin for the base case dry gas well is only $1.80/Mcf. In the majority of the jurisdictions in North America most of this margin is used to pay royalties (often $1/Mcf or more), severance taxes, property taxes, and corporate tax.

Under low gas prices, governments take comprises the vast majority of this margin. Therefore, GT0 values are high in most jurisdictions.

The toughest gas fiscal systems are in British Columbia, Louisiana, Texas, and the systems on Native American Lands in Alberta. In all these areas the GT0 values are over 90%. British Columbia, Louisiana, and Texas are all major gas producers.

Low GT0 values of less than 45% are seen in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia as well as for CBM and shale gas terms in Alberta. Other low government take values are in the other Eastern Canadian provinces and New York. The Eastern Canadian provinces have no or little gas production.

Of the major conventional gas and shale gas producing jurisdictions the best rated systems out of 98 gas fiscal systems are:

• Rank 9 & 10: New York on state and private lands.

• Rank 11 & 14: California on federal and private lands.

• Rank 15 & 16: Alberta CBM and shale gas incentive terms.

• Rank 19 & 27: Pennsylvania on state and private lands.

• Rank 25 & 26: Alberta exploration incentive terms and regular terms (ARF 2011).

The relative rating of gas fiscal systems is highly dependent on the gas price differential. Fiscal systems in jurisdictions with a positive gas price differential all feature in the top 30.

Fiscal systems in Canada vs. the US

The structure of the Canadian fiscal systems of the major producing provinces is rather different from the fiscal systems in the US. Furthermore, on average, Canada offers substantially more favorable conditions than in the US.

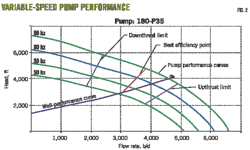

Structure. The differences in the structure of the fiscal systems can be best illustrated by comparing the two largest producing jurisdictions: the new Alberta Royalty Framework 2011 with typical terms on private lands in Texas (Figs. 1 and 2).

Alberta has a royalty that has sliding scales based on price and production; the lower the price and the lower the daily production from the well, the lower the royalty. The minimum royalty is 0% for oil and 5% for gas. The maximum rate is 40% for oil and 36% for gas. Canadian provinces do not have severance or production taxes, and property taxes are minimal.

Texas has typically flat royalties. In Fig. 2 a royalty of 25% is modeled. Texas has an oil production tax of 4.6% and some other small taxes. Marginal oil and gas wells qualify for severance tax relief. Furthermore, there is a 2.5% property tax based on the net present value of the well. This property tax therefore changes with the level of price.

Fig. 1 illustrates how the Alberta system protects the investor under low prices, because the royalties automatically become less. Therefore, even with costs of $35/bbl for the base case well and a price of $60/bbl, the investor still retains about $12 cash.

Under high prices the Alberta system is also more favorable. This is due to the low combined federal-provincial tax rate. The investor retains about $54 in the case where oil prices are $140/bbl.

Fig. 2 illustrates how the royalty and severance tax shares become very high in Texas under low prices of $60/bbl because the royalty and severance tax do not adjust downward. Therefore, the investor retains only about $3.50/bbl based on a cost of $35/bbl. Under high prices of $140/bbl, the total fiscal burden in Texas is tougher, and the investor retains about $38/bbl.

Therefore, the Alberta system is more attractive to the investors over the entire price range.

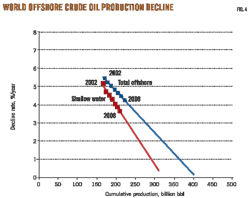

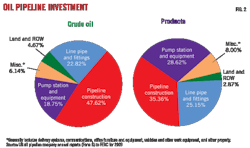

Overall level of government take. The overall government take burden in Canada is on average considerably less than in the US (Fig. 3).

This chart displays the distribution of the undiscounted government take ("GT0") for the base case oil well. The chart contains the distribution of all 90 fiscal systems reviewed: 21 in Canada and 69 in the US.

The very interesting aspect of this chart is that the systems in Canada and the US barely overlap. Canada has only a single system with a GT0 higher than 55% (Alberta Native American lands), while the US has only a single fiscal system that has a GT0 that is lower than 55% (Utah Shale Oil terms). The Utah shale oil terms would typically be used in the context of large shale oil projects.

The arithmetic average of the Canadian GT0 for oil is 42%, while the average GT0 in the US is 65%. The average GT0 for gas is 61% in Canada and 79% in the US.

In the 1997 studies of Van Meurs, Canada rated on average equal to the US. Royalties were similar. Canada had higher corporate income taxes, but the US had severance taxes and significant property taxes.

Canada increased the attractiveness to investors significantly from the typical government takes in 1997 while the US did not. This is the result of a number of factors.

Firstly, the corporate income tax rate has been reduced from a typical federal-provincial rate of 45% to a rate anticipated to be 25.5% (average for all provinces) in 2012, while the US has maintained on average a combined rate of about 38.5% for federal and state income taxes.

Secondly, several Canadian provinces created significant special incentives by lowering royalties for various reasons, such as for marginal wells, deep wells, or horizontal wells in order to encourage investment. In the US some states made improvements to encourage investments, but these improvements relate largely to severance taxes which have a lesser positive impact because severance taxes are usually a lower share of the revenues than royalties.

The Alberta improvements in gas royalties are so substantial that shale gas terms on wells with the same costs now result in a higher IRR in Alberta than in Pennsylvania despite the fact that Alberta has a strongly negative gas price differential to Henry Hub and Pennsylvania a positive differential. In other words, Alberta made its gas terms highly competitive in the North American framework.

Interestingly, the only US state that lowered royalties substantially is Utah with respect to shale oil formations on state lands. The development of such shale oil in Utah is still in the research stage. The lower royalty terms should accelerate such research and development. This is important, since the huge resources contained in the Green River oil shale formation represent the best opportunity for US self-sufficiency in oil from a supply perspective.

The overall conclusion is that Canada during the last 14 years has established a strongly investor friendly environment for the petroleum industry, while the US has remained essentially at 1997 levels in terms of fiscal burden. In fact, some of the states intend to increase government take. For instance, California and Pennsylvania are considering establishing severance taxes and Colorado is considering increasing royalties on state lands.

The difference in fiscal systems between Canada and the US is especially remarkable since Canada is the exporter and the US the importer.

North American and international government take range

As a result of the changes in Canadian fiscal terms over the last 14 years, the range of the GT0 for oil in North America is now remarkably wide.

These ranges extend from 31% in British Columbia for 3rd Tier oil discoveries to 83% in Louisiana on private lands. These ranges are in line with international ranges. Few countries have lower government takes. A number of fiscal systems in North Africa and the Middle East have higher government takes. But most countries outside North America would have fiscal systems that fit in this range.

The GT0 for gas ranges from 35% for CBM terms in Nova Scotia to 99% for terms on private lands in Louisiana. The GT0 values for gas in North America are high by international standards due to the current low gas prices.

The fact that the range of government takes in the US is similar to the worldwide range is of interest to international investors. These investors often assume that the US has a friendlier overall fiscal environment.

Many petroleum companies working internationally are headquartered in Canada or the US. The US is a large importer of oil. This is a framework in which one would expect federal and state governments to be supportive of their oil and gas production industry through more modest fiscal terms (in terms of government take).

However, governments and royalty owners in the US seem to be more focused on extracting the resource wealth from oil and gas. This is in part driven by the large private resource ownership in the US. Private royalty owners care only about their royalty and rental payments. They are the typical extractors of economic rent, and unlike governments they do not have to balance other objectives, such as employment creation, national self-sufficiency, and environmental protection.

The government take in the US therefore depends on the resource ownership. The US federal government has royalties of 12.5% on all federal lands. States and private royalty owners have higher royalties.

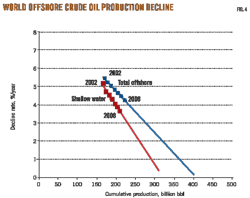

In the US the average levels of GT0 are provided in Table 1.

Investment in high cost wells mostly discouraged

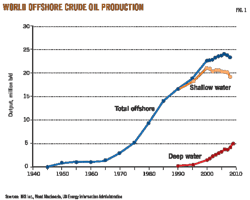

The vast majority of wells drilled in North America are wells with low cumulative production.

Wells that ultimately recover no more than of 10,000 bbl of oil and 100 MMcf of gas are common. This low recovery means that these wells are often high cost on a per barrel or Mcf basis. Yet, most North American fiscal systems discourage the drilling of such marginal wells due to the fact that royalties and severance taxes are too high for such wells. This is despite the fact that many states have so-called "stripper well" royalties or severance taxes, and some provinces have lower royalties for low productivity wells.

This is illustrated in Fig. 4, which provides the IRR for three typical wells: 10,000 bbl at a cost of $50/bbl, 100,000 bbl at a cost of $35/bbl, and 1 million bbl at a cost of $20/bbl. The chart illustrates how only about 20 fiscal systems provide material support in order to make a 10,000-bbl high-cost well economic; most of these systems are in Canada.

Most North American fiscal systems provide attractive economics as long as costs per barrel (or Mcf) are not higher than 45% of the price (for instance, $36/bbl for total capital and operating costs relative to a price of $80/bbl). At a higher ratio, such as 50%, economics rapidly deteriorate.

Once costs become 55% of price ($44/bbl costs at a price of $80), most fiscal systems in North America do not provide for attractive economics. Most systems create uneconomic conditions for high-cost wells as soon as costs are in excess of 55% of price. Therefore small wells that are at the same time high cost are typically uneconomic.

The observation that for most North American fiscal systems, wells become uneconomic at a cost of 55% of price applies actually to all wells regardless whether they are small, average, or large wells.

Fig. 5 illustrates that a 100,000 bbl oil well becomes uneconomic under the vast majority of the fiscal systems between a cost level of $42/bbl and $49/bbl, or about at 55% of price (costs of $ 44/bbl).

It should be noted that several international fiscal systems of importing nations permit fully economic operations at cost levels in the 55-60% range of price.

Most North American fiscal systems are therefore harming the level of oil and gas production by not permitting economic operations as soon as costs are 55% of price or more. However, as will be demonstrated below North America also offers considerable "upside" to low-cost operators.

At this time, the situation for dry gas wells is more serious than for oil wells. At $5/MMcf Henry Hub and a 30¢/MMbtu negative gas price differential at the field, dry gas wells become uneconomic under most fiscal systems when total capital and operating costs exceed $2.58/Mcf. Unfortunately, today many vertical dry gas wells have costs in excess of this level.

In addition to the problems related to high cost wells, most North American fiscal systems are excessively "front end loaded." This means that governments take most of the cash early in the life of a well through the use of bonuses, rentals, royalties, property taxes, and in the case of Canada, slow depreciation for bonuses, rentals, and tangible well expenditures. This dramatically delays the payout for the investor for such wells.

This is the main cause why the level of drilling of conventional vertical wells in North America is much less than it could be.

Some governments have already taken steps to reduce front end loading. British Columbia has introduced a so-called Net Profits Interest ("NPI"), which is a royalty based on profit sharing. Due to this fiscal initiative, shale gas drilling is now taking place in the Horn River basin despite the very high costs and the strong negative gas price differential.

North American fiscal systems offer considerable upside

There are no or only modest "rent-skimming" systems in North America even though such systems exist in a wide variety of nations internationally.

It is common internationally now to find production sharing contracts whereby the profit oil sliding scale is based on an R-factor or and IRR based scale or other sliding scale with the objective to increase government take under more profitable circumstances.

Also special resource taxes increase the government share substantially under higher profits. In the absence of "rent-skimming" systems, profits increase much faster than the rate of price increases or cost decreases.

Canadian systems with sliding scales based on price or production are not structured in a way to take a considerable share of the upside.

Therefore, if oil and-or gas prices would increase substantially over the coming years all fiscal systems in North America offer very substantial "upside" for investors.

Such upside also applies to "sweet spots" in North American petroleum reservoirs that offer low cost operations on a per barrel or Mcf basis. Investors that are able to identify such attractive conditions will be rewarded with levels of profitability that are highly attractive.

An instructive test to carry out is the so-called "bonanza economics" test. This test evaluates a very large well under low costs and high prices. Following are the "bonanza economics" results for gas. In this case a deep, 10 bcf dry gas well is selected under $8/MMbtu Henry Hub and 60% of the base case costs ($1.75/Mcf for capital and operating costs). Fig. 6 provides the top 20 fiscal systems in this case. The NPV10 values range from $24.7 million to $16.7 million for a single well.

Of the major producers, Alberta has established favorable conditions for shale gas that include a 5% royalty for the first 3 years of production as well as a deep well credit with a maximum of $8 million. Shale gas plays in Alberta therefore offer tremendous upside. New York and California also provide favorable upside.

North American shale plays

The considerable interest in shale plays in North America is directly driven by the attractive upside that some of these plays offer.

It is not unusual to have shale gas wells with expected ultimate recoveries in excess of 3 bcf or shale oil wells in excess of 300,000 bbl.

In order to identify the most attractive shale plays, a special study is included in the report on 16 shale plays based on 64 different applicable fiscal systems. This rating is based on assessments of the actual costs, prices, and production profiles of typical wells in each play. Various plays cross over in various jurisdictions that in turn have different fiscal terms depending on the resource ownership. This results in the applicability of 64 fiscal systems.

The study indicates that the most attractive shale gas plays are the Montney in Alberta and the Marcellus in Pennsylvania and New York.

Nineteen shale gas plays are economic, using a 10% real discount rate, at a Henry Hub price of $4.50/MMbtu (Fig. 7).

All core areas of shale plays, except for the Woodford play, are economic at $5.50/MMbtu based on typical average costs in this study on a risked basis.

The fiscal incentives provided by Alberta play an important role in the favorable rating of the Montney play. BC also provides incentives for the Montney play, through its special marginal gas well terms, but these incentives only apply to relatively modest producers in this play.

The most attractive shale oil play is the Bakken formation in Saskatchewan. This rating is in large part the direct result of the strong fiscal incentives provided by Saskatchewan. However, the Bakken plays in Montana and North Dakota as well as the Eagle Ford oil play in Texas have very attractive NPV10 values.

Few fiscal incentives for new technologies and unconventional resources

Although currently some of the "hot spots" of shale gas and shale oil drilling offer excellent economics, the vast majority of the unconventional resources provide more mediocre profitability.

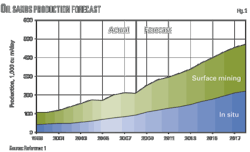

Yet, the production potential of these new resources is huge.

Despite the huge potential of unconventional resources, few governments offer incentives for the development of these resources.

The only jurisdictions that offer significant incentives are:

• Alberta for shale gas and CBM.

• Manitoba and Saskatchewan for horizontal oil wells in the Bakken shale oil play.

• British Columbia with a novel Net Profits Interest scheme to develop the Horn River shale gas deposits.

• Utah with reduced royalties to develop shale oil projects.

To provide an example, Fig. 8 illustrates how the horizontal well incentives in Manitoba reduce government take by about 14 percentage points to a level of 33%.

Several US states offer some incentives through severance taxes, but the effect of these incentives is often very modest. Usually the decrease in the overall GT0 is 2 percentage points or less.

Fiscal systems for gas are dysfunctional

Gas prices are delinked from oil prices, yet fiscal systems are still linked. This means that fiscal systems for gas have now become dysfunctional in most jurisdictions.

The North American gas market is now almost completely delinked from the international oil market. At the same time gas prices relative to oil prices on a btu basis have dropped significantly since 2003, which was the year in which oil prices began their increase. In 2003 one could divide the oil price by 8 to arrive at the gas price. Today one needs to divide the oil price by 20 or more.

Given that the price relationship between oil and gas has changed dramatically since 2003, most fiscal systems for gas in North America have now become dysfunctional.

It has been a tradition in North America for more than a century that royalties and severance taxes are the same for both oil and gas. If the royalty for oil is 12.5%, the royalty for gas is also 12.5%. This overall concept is deeply ingrained with governments in North America.

This policy tradition can no longer be maintained if North America seeks to benefit from its extensive gas resources through increases in gas production for enhanced self-sufficiency, improved environmental conditions, and sustained low prices for consumers.

Governments have yet to fundamentally recognize that natural gas from an economic perspective is now a different resource than oil. Therefore, it is time that governments start to differentiate their fiscal terms by providing more beneficial terms for gas than for oil, in particular under low gas price conditions.

Alberta is the only jurisdiction in North America which has created a framework that matches the new economic circumstances for gas.

Recommended fiscal changes

If North America wants to benefit from the production of large unconventional and high cost conventional resources, significant change in fiscal terms is required in the US and some Canadian provinces. North American jurisdictions need to implement two concepts:

• Differentiation between oil and gas terms.

• Reduction of front end loading for both oil and gas.

Differentiation between oil and gas. With respect to the differentiation between oil and gas the following recommendations could be made:

• The US Bureau of Land Management has consistently maintained a royalty of 12.5% for oil and for gas. This policy should change. The royalty for gas should be set at a much lower level as long as Henry Hub prices are low.

• States should reduce gas royalties on state lands in a similar manner despite the fact that often higher royalties are earned on private lands.

• States and provinces that have already price sensitive gas royalties should bring their gas price levels in line with current gas price conditions.

• States should start to differentiate between severance tax rates for oil wells and for gas wells, with lower rates for gas.

Reduction of front end loading. The following recommendations could be made to reduce front end loading:

• The Canadian federal government should reduce the relative front end loaded nature of the corporate income tax system as it applies to oil and gas.

• States and provinces should provide an exemption or lower royalty rate for gas and for oil for an initial period, initial volume of well production, or initial level of gross revenues.

• More states of the US should provide an exemption or lower rates for severance taxes for an initial period, initial volume, or initial level of gross revenues.

For large unconventional or high cost resource projects it can be recommended to introduce profit sharing royalties or taxes, similar to the Alberta royalties for oil sands, the net profits interest for shale gas in Northeast British Columbia, the royalties in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia offshore, or the petroleum profits tax in Alaska.

The authors

Gerald Kepes is a partner and head of PFC Energy's Upstream & Gas practice. The company's upstream and gas consulting practice and expertise focus on regional and global gas and E&P strategies, portfolio management and fiscal systems, international oil and gas companies, national oil companies, the oil field and drilling services sector, and competition and performance therein. Kepes has an MA in international relations from Johns Hopkins University, an MS in geology from the University of New Mexico, and a BS cum laude in geology from the University of Dayton.

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com