Black Sea region stands at energy crossroads

The Black Sea energy landscape is going to change dramatically over the next 5-10 years, as the region's nations pursue aspirations not only to become transport hubs for oil and natural gas supplies moving into Europe but also to boost their own hydrocarbon output.

Divergent or even conflicting paths, however, still need to come together if the region is to reach its full potential, Black Sea events having ripple effects on Southeast Europe, Russia, the Caspian Sea, Middle East, and ultimately the European consuming markets.

The Nabucco and South Stream pipeline projects are just the visible part of the energy game emerging in the region. Statements in the context of the first Black Sea Energy and Economic Forum (OGJ, Sept. 21, 2009, p. 50, and Oct. 12, 2009, p. 27) and other recent events in the region allow greater understanding of the often divergent interests and strategies of the countries bordering the Black Sea. This article examines each country in turn.

Ukraine

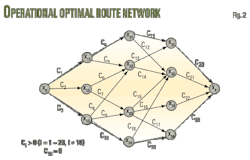

Ukraine remains the main transit country for Russian oil and gas exports to Europe through the pipeline infrastructure developed by the former Soviet Union. About 22% of total Russian oil exports cross or are consumed in Ukraine. The natural gas percentage is even higher at more than 80% (Fig. 2). Although Ukraine has stepped up exploration efforts, its oil and gas production have remained flat for the last decade, covering slightly more than 20% of domestic oil consumption and almost 30% of gas consumption.1

Ukraine's strategic goals include retaining its position as the main energy transit hub for exports to Europe, decreasing its dependence on Russian oil and gas by increasing domestic production, and diversifying its import sources by directly importing Caspian oil and gas.

The country, however, faces a number of obstacles in reaching these objectives. Economic and financial woes coupled with domestic political strife and deteriorating relationships with Russia endanger Ukraine's status as the main Russian export transit country. The Soviet-era oil and gas pipeline infrastructure is old and deteriorating rapidly, and Ukraine cannot afford to maintain and upgrade it. National oil and gas company Naftogaz is technically bankrupt and cannot support development of domestic oil and gas.

Pipeline projects initiated by Ukraine to diversify oil and gas imports, such as the White Stream (Georgia-Ukraine-EU) gas pipeline and the extension of the Odessa- Brody oil pipeline to the Baltic Sea port of Gdansk (Poland), have stopped moving forward.

Ukrtransnafta, operator of the Ukrainian oil pipeline system, stopped Russian oil shipments in the Odessa-Brody pipeline in October 2009 for several weeks—forcing Lukoil's Black Sea Odessa refinery to halt activity—and reversed its flow to import oil directly from Azerbaijan instead. SOCAR, the Azeri national oil and gas company, opened an office in Kyiv on Oct. 12 and has confirmed negotiations to buy another Black Sea refinery in Ukraine, the Kherson refinery.

These actions worsened Russian-Ukrainian relationships, already strained by nearly continuous natural gas import volume and transit fee disagreements. Russia and Ukraine signed a new gas supply contract after the winter 2008-09 supply crisis, but in October 2009 Ukraine announced a desire to reopen negotiations in an effort to reduce contracted volumes to 33 billion cu m/year in 2010 from 42 billion cu m/year in 2009.

Ukraine also seeks to renegotiate gas transit fees, considering Naftogaz's current annual transit revenue of roughly $2.5 billion to be less than adequate. Gazprom is strongly opposed to reopening the contract and the Ukrainian government has warned that, although it will not disrupt gas transit to Europe during winter 2009-10, it cannot guarantee transit for 2010-11 without a new contract.2

In its bid to increase domestic oil and gas production, Ukraine has also antagonized Romania regarding the exclusive economic zone boundary between the two countries in the northwest corner of the Black Sea (Fig. 3).

Ukraine faces an uphill battle the next 5-10 years to maintain its preferred transit country status, as internal political fights continue, competition intensifies from southern corridor projects bypassing the country, and Russia continues to block direct access of Caspian producers to Europe through Ukraine.

Romania

Romania is a traditional oil and gas producer and was for a long time an oil exporter. Domestic production, however, is declining rapidly. The country produced 99,000 b/d of oil and 11.5 billion cu m of natural gas in 2008, covering 80% of domestic gas consumption, but only 44% of oil consumption.

As a member of the European Union since 2007 with more than 500,000 b/d of oil refining capacity and a well-developed oil and gas pipeline infrastructure, Romania presents an interesting potential access point to European markets for non-EU suppliers, especially Caspian producers.

Romania spent the past 20 years without a clear long-term energy strategy, other than opposing any large Russian-led project. The Romanian Energy Strategy Plan for 2007-20 does not mention any regional or European strategic objective for the energy sector.

Signs of a more structured energy strategy, however, have recently emerged. The main tenets of this strategy seem to be close cooperation with Caspian producers to allow them to access to EU markets while Romania diversifies from Russian supplies, coupled with an increased push to revive domestic oil and gas production and diversify the primary energy mix.

KazMunaiGaz, the Kazakh national oil and gas company, acquired Rompetrol in 2007. Rompetrol has distribution networks in 13 countries. Romania also signed a strategic partnership agreement with Azerbaijan and negotiations between Romanian authorities and SOCAR have intensified, SOCAR promising during October 2009 talks to supply Romania with 7.3 billion cu m/year of gas if Nabucco is the first-built among the competing regional pipeline projects.

SOCAR is also interested in investing in refining capacity in Romania and, although the Romanian government has privatized all refineries, it has also announced a large state subsidy for RAFO Onesti, a money-losing privately owned refinery, intensifying speculation regarding cooperation with SOCAR regarding the facility.

Romania has unconditionally supported Nabucco since its inception and was not invited to be part of South Stream. It was also one of the initiators of the Pan-European Oil Pipeline (or Constanta-Trieste pipeline), shelved in September 2009 as Croatia reconsidered its energy project priorities and focused on projects along the Adriatic coast. Romania has also started negotiations to participate in the still-nascent White Stream project, strongly backed by Azerbaijan.

Romanian business leaders discussed the possibility of shipping LNG across the Black Sea during the Black Sea Energy and Economic Forum, an option also mentioned in late October by Azeri officials. But this option seems to be a long shot without switching to cheaper, quicker CNG instead (Fig. 4). In the meantime, the Romanian government earmarked €2 billion over the next 10 years for upgrading the country's gas transmission network, connecting it to neighboring countries, and increasing underground storage capacity.

Romania on Sept. 3, 2009, launched its tenth oil and gas production licensing round, with permits to be awarded early-2010. The round offered 30 oil and gas exploration blocks, 11 of them offshore in the Black Sea.

A February 2009 decision by the International Court of Justice in the Hague settling competing claims by Romania and Ukraine regarding a 12,000 sq km offshore area thought to contain as much as 100 billion cu m of gas and 73 million bbl of oil reserves allowed opening of previously unavailable offshore blocks.3 The ICJ awarded 9,000 sq km to Romania and the balance to Ukraine4 and both countries accepted the decision.

Romania could become a bridge to Europe for Caspian production if it can separate internal politics from the management of its energy sector, improve the transparency of the exploration licensing process, and implement energy infrastructure projects geared toward helping it become a viable oil and gas transit country.

Bulgaria

Bulgaria, the other EU member in the Black Sea region, imports more than 85% of its gas and 95% of its oil from Russia. Bulgaria and Slovakia were the worst hit states during the January 2009 gas crisis in Europe. Domestic oil and gas production remains marginal (Figs. 5 and 6).

The 2002 Energy Strategy of Bulgaria document says the country should become the energy center for the Balkans. Domestic politics, however, have prevented updating this strategy to account for new energy trends and the country's 2007 integration into the EU.

Previous governments strongly supported Russian-backed projects such as the South Stream gas pipeline and Burgas-Alexandroupolis oil pipeline, while also participating in competing projects such as Nabucco or the AMBO (Burgas-Vlora) oil pipeline. The government installed in July 2009 started to back away from these projects, only to restate interest in October 2009.

A new draft of the national energy strategy document met with resistance from interests concerned it will create energy production overcapacity and encourage corruption in state-owned energy companies. A report published in September 2009 by the Center for the Study of Democracy says the energy sector "remains one of the least transparent and of highest corruption-risk sectors in Bulgaria."5

The report recommends, among other things, revising the new national energy strategy draft, energy supply diversification in the nuclear sector, and improvements in gas storage facilities and the gas transmission network, as well as more transparency and openness in general.

Bulgaria is well-positioned to become an energy hub for the Balkans, and the region has a promising potential for oil and gas infrastructure projects,6 7 but the country has to define both its Balkan cooperation projects and how it will reconcile this Balkan-focused strategy with participation in wider-reaching energy projects.

Turkey

Turkey's growing economy depends on imports for almost 95% of oil consumption and almost 90% of gas consumption.8 Turkey's pipeline and LNG terminal infrastructure, however, allow it the most diversified range of oil and gas imports in the Black Sea region, accessing supplies from the Middle East, Caspian Sea, Russia, and Africa.

Turkey's energy strategy centers on four main axes:

• Becoming the main energy transit hub between oil and gas producing regions and European markets.

• Diversifying oil and gas import sources.

• Diversifying its energy mix.

• Dramatically increasing domestic oil and gas production.

Turkey lies in the transit routes from Caspian, Russian, and Middle East producers to the European markets. Besides its existing oil and gas pipelines and LNG terminals, Turkey has been involved since the beginning in the Nabucco project and in 2009 joined the South Stream project. Turkey officially approved laying South Stream in its territorial waters and began preliminary route survey work Oct. 20, 2009. Turkey and Russia have also discussed a potential Blue Stream 2 gas pipeline in the Black Sea to Samsun.

Turkey also has two oil pipeline projects—Trans-Anatolia (or Samsun-Ceyhan) and Trans-Thrace—competing against the AMBO and Burgas-Alexandroupolis pipelines to bypass the Bosporus. The Trans-Thrace pipeline, promoted by local Tun Oil, is dormant, while the Trans-Anatolia pipeline, promoted initially by Italy's Eni and Turkey's Calik Holding, received a boost Oct. 19, 2009, when Russia joined Italy and Turkey in signing a joint agreement for building the pipeline. Russian companies Transneft and Rosneft have cosigned with Eni and Calik Holding a memorandum of understanding for construction of the pipeline (see table). On Oct. 27 Russia and Turkey also signed an agreement to build a refinery on the Samsun-Ceyhan pipeline.

Turkey's state Turkish Petroleum Corp. is a shareholder in the Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli and Shah Deniz fields in Azerbaijan and has exploration and production interests in other countries in the region, such as Turkmenistan, Syria, Iraq, Egypt, and Georgia. Turkey is also using its historical and cultural ties to the Middle East region to try to secure gas supplies for the planned pipelines, holding 2009 discussions with Iraq, Iran, and Qatar to secure gas for Nabucco.

Turkey has also improved its relations with Armenia, which is starting to be viewed by some as an alternative to Georgia as a transit route from the Caspian Sea. The move angered Azerbaijan, which has a long-term conflict with Armenia, prompting Azeri threats in October 2009 to avoid Turkey as a transit country for gas from the Shah Deniz 2 project and instead study an LNG or CNG route to the western coast of the Black Sea.9

Turkey is actively diversifying its energy mix, having ratified the Kyoto protocol and adopted laws encouraging investment in renewable energy production. Renewable sources, mostly hydro, already meet 20% of Turkey's primary energy needs and Turkey has three nuclear plants planned.

TPAO is leading Turkish efforts to increase domestic production of oil and gas, particularly from the Black Sea. In 2006 TPAO initiated a $350 million joint venture with Petrobras covering two offshore Black Sea blocks and has also actively explored the area on its own.

Its other major Black Sea exploration partner since 2008 is ExxonMobil.10 TPAO's CEO stated as recently as October 2009 that 10 promising areas in the Black Sea could contain recoverable reserves of up to 10 billion bbl oil and 1.5-2 trillion cu m gas, enough to allow Turkey to cover its domestic consumption and become an oil and gas exporter.11

TPAO started gas production in the Black Sea in 2007 but still has a lot of work to do to prove reserves of the most promising prospects and finance exploration and development, needing at least $100 billion and advanced deepwater technology. TPAO does not expect production from these fields before 2020. ✦

References

1. US Energy Information Administration, "Ukraine Energy Data, Statistics and Analysis," August 2007.

2. RIA Novosti, "Ukraine cannot guarantee Russian gas transit next year," Oct. 13, 2009.

3. Deloitte Petroleum Services, "10th Romanian Bidding Round," September 2009.

4. International Court of Justice, "2009, 3 Feb., General List No. 132—Case Concerning the Maritime Delimitation in the Black Sea (Romania vs. Ukraine)—Judgment," 2009.

5. Center for the Study of Democracy, Brief No. 18, "Better Governance for Sustainable Energy Sector of Bulgaria: Diversification and Security," Oct. 8, 2009.

6. Economic Consulting Associates, Penspen, European Integrated Hydrogen Project, "SEE Regional Gasification Study—Draft Final Report," 2007.

7. Kovacevic, A., "The Potential Contribution of Natural Gas to Sustainable Development in South Eastern Europe," Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, NG 17, March 2007.

8. US EIA, "Turkey Energy Data, Statistics and Analysis," April 2009.

9. Jewkes, S., and Yevgrashina, L.,"Turkey says ready to pay more for Azeri gas transit," Reuters, Oct. 19, 2009.

10. Turkish Petroleum Corp., "TPAO Annual Report," p. 11, 2009.

11. "Turkish state firm to drill Black Sea in January," Bloomberg, Oct. 5, 2009.

The author

More Brand Name Current Issue Articles

More Brand Name Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com