A new Gulf of Mexico offshore damage prevention and notification “one-call” system, operating in conjunction with existing onshore systems, offers a cost-effective means of preventing damage to offshore infrastructure. The system is entirely web based, with all incoming locate requests addressed on line. It services four of the US Minerals Management Service planning areas for the US Outer Continental Shelf.

Background

All states have some form of one-call system excavators and the operators of buried facilities can use to avoid excavation damage. These systems provide a centralized communications platform connecting excavators with the operators of buried facilities in the planned excavation area. State and federal laws and regulations codify the requirements governing these systems. While these systems have proven their worth in preventing excavation damage and incidents, until recently a notification system addressing offshore excavation activities has not been available.

In February 2009 GulfSafe LLC, Dallas, a wholly owned subsidiary of Texas Excavation Safety System Inc. (TESS), started a web site addressing offshore damage prevention and notification with the goal of eliminating preventable damage to subsurface infrastructure in the Gulf of Mexico and Straits of Florida. TESS operates one of the largest one-call centers in the US, processing more than 2 million incoming notifications/year, and has more than 20 years of notification system experience.

RCP Inc., Houston, provided appropriate GIS datasets for development of the Gulf of Mexico one-call notification system. This article discusses how the databases were acquired and prepared for implementation into GulfSafe’s system and describes how the system functions.

Increasingly crowded

America’s critical infrastructure, including energy and communication systems, is expanding offshore, with the Gulf of Mexico one of the most active locations. Innovative technology is required to address the potential threats from this rapid development. Protection of this crucial energy source is a matter of economic and national security.

The roughly 43 million leased OCS acres in the Gulf of Mexico account for about 15% of US domestic natural gas production and 27% of domestic oil production.1 More than 33,000 miles of pipelines crisscross the bottom of the gulf, connecting more than 4,000 platforms to the coast.2 These production platforms range in size from single well caissons in 10-ft water depths to large complex facilities in water depths greater than 7,000 ft.3

Leases for wind farms and wind-produced electrical energy are under development in the shallow waters of the gulf. The first wind farm agreement in the GOM with the Texas General Land Office and wind developer Galveston-Offshore Wind LLC to construct a wind farm about 7 miles off Galveston Island was signed in October 2005.4 Leases will likely expand into deeper waters.

StatoilHydro recently allocated 400 million NOK ($78 million) to floating a Siemens turbine in more than 200 m water in the North Sea about 10 km off Karmoy, on Norway’s southwestern tip. The installation took place atop a conventional oil and gas platform in water about 10 times deeper than conventional offshore wind-turbine foundations.5

Tentacles of electrical wire from turbine locations will eventually abound on the ocean floor, joining the thousands of miles of telecommunications cables already traversing the ocean bottom. Three communications cables affecting web and telephone services were severed recently, affecting much of the Middle East. A ship’s anchor cut one of the cables. Repairs require pulling cable ends to the surface and can take several days.6 Several government agencies have jurisdiction over areas of the Gulf of Mexico, with some overlapping. No one agency or organization, however, is available with a centralized, automated method to coordinate new developments.

Offshore one-call

Unlike a traditional one-call operation, the offshore notification process is completely web-based. All notifications travel through www.gulfsafe.com and all member or facility operator notifications are made on line. Technical and user support occurs online or by phone.

Use of the service to request notifications of activity is free. Member companies pay the costs to help prevent damage to their structures. The service shares notification requests with all five traditional one-call centers on the Gulf Coast, ensuring continuity between onshore and offshore operations. The new system services four of the MMS OCS planning areas: the Western Gulf of Mexico (Texas); Central Gulf of Mexico (Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama); Eastern Gulf of Mexico (Florida), and Straits of Florida (Florida Keys).

The offshore notification system uses GeoCall software for its web-based service. The software manages member information, incoming tickets, and transmitting tickets to members. The platform has been expanded to operate in a maritime environment and integrate with Gulf of Mexico land-based one-call systems.

Data acquisition

Acquired data sets filled the following categories:

- Boundaries.

- Blocks, tracts.

- Pipelines.

- Wells, platforms.

- Biological areas, including fisheries and wildlife.

- Artificial reefs.

- Wrecks, obstructions; e.g., Fisherman’s Gear Compensation Fund obstructions, marine debris.

- Ordinance disposal areas.

- Military warning areas.

- Archeological sites.

- Fairways, designated anchoring areas.

- Telecommunications systems.

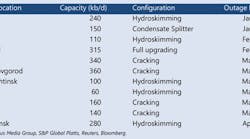

State or federal agencies provided most data and a hard copy manual documented the paper trail for both future updating and reference purposes. The accompanying table provides a summary of file types available for the five Gulf of Mexico areas and the number of providers.

Key federal agencies contacted included US Army Corps of Engineers (ACOE), US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), National Marine Sanctuaries Program (NMSP), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), and the MMS. The MMS website was a key source for OCS information.

Downloading databases in each format occurred during the data collection phase. Using a .pdf format allowed easy access and review of the information. Potential terrorist activities have prompted the National Pipeline Mapping System (NPMS) not to release pipeline information to the general public, raising the importance of its inclusion in this restricted system.

Key state agencies included:

- Texas:

- Louisiana:

- Mississippi:

- Alabama:

- Florida: Texas Land Office, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Railroad Commission of Texas (TRRC). Louisiana Geographic Information Center, Louisiana Digital GIS Map, Louisiana Oil Spill Coordinator’s Office, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Louisiana Department of Natural Resources Coastal Management. em Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality, Mississippi Department of Marine Resources, Mississippi Fish and Wildlife Service, Mississippi State Oil and Gas Board (MSOGB). Alabama State Oil and Gas Board (ASOGB), Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Florida State Oil and Gas Board.

A direct correlation existed between oil and gas activity in a state and availability of searched data. Texas and Louisiana had an abundance of information.

Texas has 16 gulf-front counties, and a plethora of information was available from the TRRC and Texas Land Office for building the databases. Louisiana accounts for about 90% of the nation’s offshore oil and gas production and has land and water interstate gas and liquid pipelines totaling 32,514 miles and intrastate pipelines totaling 11,267 miles.7

Mississippi has three counties, Hancock, Harrison, and Jackson, bordering the gulf. The state’s oil and gas board has stated no oil and gas production or pipelines requiring permitting are allowed in near-shore waters, but several OCS pipelines come ashore in Mississippi. The state has since delegated oil and gas activity to the Mississippi Development Authority.

Alabama has two counties, Mobile and Baldwin, bordering the gulf. NPMS says ExxonMobil, Shell, Legacy, and others own the offshore assets that include 9,424 miles of onshore and offshore hazardous liquid, gas transmission, and gas gathering pipelines. Alabama’s oil and gas board said these pipeline data were proprietary.

Florida has 13 counties adjacent to the Gulf of Mexico with only one offshore pipeline so far entering the state landing in Manatee County. Owned by Gulfstream Natural Gas System LLC, the line connects south Alabama to Tampa Bay, Fla., covering 419 offshore miles. No oil and gas wells exist in Florida’s state waters and all oil and gas leases have been purchased by the state.

Standardizing data

Checking acquired data ensured consistency and accuracy. Sources often provided data in multiple tables that were combined into one. Importing the resulting files into Environmental Systems Research Institute Inc’s. (ESRI) ArcInfo as coverage files and converting them into shape files, allowed them to be viewed and checked in GIS.

Tables with X and Y coordinates were standardized and screened for corrupt data. Data with errors that could not be corrected were eliminated. Converting X and Y coordinates into decimal degrees and storing them in numeric fields with Y data (longitude) changed to negative values allowed importing the data into GIS as an event layer on a map. Viewing finished data projected and defined in the proper geographic coordinate system on the map provided additional quality control.

Placing all data into a geodatabase format created a base map of the Gulf of Mexico with layers designed to be easily turned on and off in the table of contents. Layers linked the path to the data within the geodatabase and provided labeling and symbology information.

A contracted commercial source provided pipeline, platform, and interconnect information for the system, updated every 6 months. When database information was client-privileged or restricted, GulfSafe agreed to acquire the data directly from participating clients.

Updating the various databases on a regular basis is key to the proper functioning of the one-call system. The MMS database information on pipelines, platforms, blocks, well completions, and company information is available monthly. The potential for updating other databases varies.

References

- http://www.mms.gov/offshore, Offshore Energy and Minerals Management (OEMM) (last update Feb. 18, 2009).

- http://www.gomr.mms.gov/homepg/whatsnew/, Feb. 2, 2005.

- “MMS: 52 production platforms, 3 jackups, 1 platform drilling rig destroyed by Ike,” http://www.drillingcontractor.org., Sept. 29, 2008.

- Texas General Land Office, Oct. 24, 2005.

- “Wind Power Moves into Deep Waters. A floating wind turbine is planned for 10 kilometers off Norway.” Peter Fairley, Technology Review. June 4, 2008.

- Fort Worth Star Telegram, Dec. 22, 2008.

- “Improving the Safety of Marine Pipelines,” Committee on the Safety of Marine Pipelines, Marine Board, National Research Council, The National Academies Press, 1994.

The authors

Kenneth T. Palmer ([email protected]) is a senior compliance consultant at RCP Inc., Houston. He has more than 30 years’ experience in the oil and gas, government, and chemical industries. He holds a PhD from the University of Missouri (1992).

W.R. Byrd ([email protected]) is president of RCP Inc., an engineering and regulatory consulting firm headquartered in Houston. He has 29 years’ experience in the oil and gas industry and is actively involved in several industry committees. He has a BS and MS in mechanical engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology (1981, 1982).

Jack Garrett is director of regulatory services at GulfSafe LLC, with 18 years’ experience working in damage prevention and utility management. Garrett spent 8 years of his career before his current position working for Texas Excavation Safety System Inc. (DigTESS). He earned a BS from the University of Missouri at Kansas City (1990).