EPRINC: Cap and trade will hurt and help oil industry

A carbon cap and trade system and other initiatives to curb greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions will hurt the petroleum industry overall but also will create opportunities for some oil companies to cash in, said officials at Energy Policy Research Foundation Inc. (EPRINC), Washington, DC.

Political momentum is building in the US for legislative and regulatory action to constrain greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

“Some actions, such as the mandating of large quantities of ethanol, may have other purposes, but their policy rationale in part is to control GHGs. Others, such as cap and trade, are directly aimed at curbing these gases,” EPRINC reported.

The report acknowledged, “Climate scientists have generally concluded that the Earth has been warming and that anthropomorphic activities, mainly the combustion of fossil fuels, have contributed to this warming. Though there remains considerable uncertainty regarding the magnitude of the anthropomorphic effect and only limited understanding of natural climate variation, model projections indicate that if current trends continue, there are significant chances that the Earth will experience a warming climate with adverse consequences such as increased numbers of severe weather events, rising sea levels, drought, and the spread of tropical diseases.”

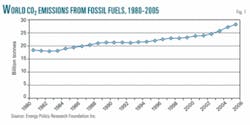

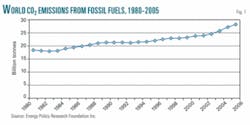

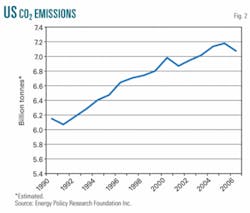

According to those scientists, annual emissions rose to 28 billion tonnes from 18 billion tonnes in 1980-2005 (Fig. 1). “Since carbon dioxide emissions represent better than three quarters of worldwide GHG emissions, the trend in GHG emissions is roughly similar to that for CO2,” EPRINC said. “The absolute level of GHGs increased steadily in most years between 1990 and 2000 but has increased only slightly since.” During 1990-2006, US GHGs increased by 15% (Fig. 2).

“In the US, petroleum use generates the most CO2, coal the next most, and natural gas the least,” EPRINC reported. CO2 emissions from all three sources have trended upwards in the US since 1990. Yet despite that trend, the report said, “The GHG intensity of US gross domestic product has steadily dropped since 1990 and is now more than 27% below what it was in 1990.” During 2002-06, US GHG intensity dropped almost 10 percentage points of the 18 percentage points that President George W. Bush set as the national objective through 2012.

The report argues that the US record on curbing GHGs “has been as good or better” than that of most other developed countries. But concern among policy makers has grown with successive reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change emphasizing potential dangers of climate change. “While questions about the science of climate change are not fully settled, there is growing sentiment both at the national and state levels that strong, binding measures are necessary to curb increases in US GHGs and then to reduce them,” EPRINC said.

As a result, legislators are pushing to reduce GHG through new laws and regulations at the state and federal levels. “It appears increasingly likely that some will be promulgated or enacted into law. Prominent among these is ‘cap and trade,’ in which the nation’s GHG emissions would be capped, allowances to emit these gases given out or sold by the government, and parties receiving them allowed to transfer them in organized markets. A bill containing such a cap and trade system passed the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee in December 2007, and a close substitute was deliberated on the floor,” the report said.

Recent legislation mandating substantial increases in the use of ethanol and other biofuels was justified in part because it would reduce GHG. “The same legislation mandates increased Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards, again in part to reduce GHGs. In addition, the state of California has mandated a Low Carbon Fuel Standard to reduce carbon emissions in that state, and a similar provision is contained in the Senate’s recently debated cap and trade bill,” the report stated.

GHG emission targets under cap and trade proposals likely will change the US energy makeup. If the targets in S.2191 are to be met, then GHGs per capita in the US would have to drop 30% by 2020 and 50% by 2030.

“Barring near term viability of large scale carbon dioxide sequestration, this implies a sharp drop in the use of fossil fuels, to be replaced by nuclear power, renewable energy sources, or energy efficiency measures,” said EPRINC in the report. “Further, the gap between how much fossil energy would have been consumed and what actually could be consumed would steadily grow. For example, if emissions from these fuels otherwise would have risen by 1%/year, a reduction of 10% from 2008 levels by 2020 would imply a reduction of almost 23% from what otherwise would have occurred.”

How it works

Under a cap and trade system, annual US GHG emissions would be capped at some chosen quantity, with emission rights (or allowances) given or auctioned to prospective emitters, expressed in terms of tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions.

“A single allowance might provide its owner the right to emit 1 tonne of carbon. An emitter would be required to submit an allowance to the government for each tonne of carbon emitted. Each year would have its own set of rights, distributed in accordance with the overall national target for that period, and emitters would be responsible for turning in allowances equal to the amount of carbon they emitted,” EPRINC explained.

Emission rights would be transferable, so that those needing less than the amount they hold could sell them to others who needed more. The value of these emission rights would be determined by the amount of national constraint on carbon and demand for the rights, which in turn would be determined by the demand for goods and services resulting in GHG emissions.

“The general idea is to distribute emission rights to producers, processors, or importers of fossil fuels and let them raise prices to their customers to cover the costs of these rights. Thus end users would pay more for energy but would not be required [to acquire] emission rights. Because coal is most carbon intensive, its price would rise relative to oil and gas, while the price of oil would be up relative to clean burning natural gas,” said EPRINC.

A cap and trade system might include the “safety valve” of a government guarantee to sell additional emission rights if the price exceeds a prespecified ceiling in a given year. But environmentalists oppose that, EPRINC said. The system also might feature a floor price for allowances to encourage investors to invest heavily in energy efficiency technologies.

“Other possibilities include allowing holders of emission rights to bank part of a given year’s rights for future use,” EPRINC said. “They also might borrow against future emission rights, to be paid back with interest by turning in more emission rights per unit of carbon emitted than the amount borrowed.”

Various proposals would reduce US GHGs at different rates, but the general idea is to establish an initial target near present levels to be reduced over time. As initially proposed, S.2191 would distribute 5.2 billion allowances in 2012 to covered facilities (comprising about 80% of all emissions) and then reduce that amount by 96 million tonnes annually during 2012-50. That would result in a 70% reduction in US GHGs from 2005 levels. However, some proponents have called for greater cuts of as much as 85%.

An international system

A US cap and trade system would be part of an international emission rights trading system. Under the Kyoto protocol, offsets can be obtained through joint implementation projects among developed countries and via the Clean Development Mechanism in developing countries. Many cap and trade proposals would enable emitters to secure offsets from domestic agricultural sources. Yet to be determined is whether US parties could trade within the European Trading System (ETS).

“Many environmentalists advocate auctioning emissions rights, while many in business want free allowances to compensate for rising energy costs. Most federal proposals would compromise with a low initial number of auctioned allowances that would rise over time,” said EPRINC. As introduced, S.2191 would have auctioned 22% of the allowances initially, increasing to 100% in 2036.

Because allowance trading likely will be international, the price of allowances in the US will differ little from that in Europe and elsewhere. According to the report, “A preliminary assessment of S.2191 suggests that price would be no more than $20/tonne of CO2 in 2015, or about 20¢/gal of petroleum product. However, the present price per ton in the ETS is about $40/tonne, and Charles River Associates projects that under S.2191 the price of allowances would be closer to $35-60/tonne, or 35-60¢/gal. Both assessments see the price of allowances rising with time.”

Since the system fixes the quantity of allowable fossil energy supplies in any given year while demand remains uncertain, prices are likely to be volatile. In years when demand is great and permits are few, prices could spike; in years when demand is weak and permits are plentiful, prices would fall.

“With upwards of $100 billion in allowance value at stake each year, a variety of interests can be expected to compete, expending resources in the process. In the aggregate, such competition may lead to hundreds of millions if not billions of dollars in expenditures, none of it enhancing the wealth of the country,” EPRINC said.

Continued immigration and a relatively high birthrate are expected to increase US population to 336 million in 2020 and 364 million by 2030 from 300 million at present. Under S.2191, current per capita emissions of 19 tonnes of carbon equivalent would be reduced by 30% in 2020 and by 50% in 2030.

“Possibly offsets, large scale carbon sequestration, and alternative forms of energy will be sufficiently inexpensive that per capita energy consumption could be sustained. But more likely, fairly dramatic changes in lifestyle would be necessary to achieve the targets,” EPRINC said.

Meanwhile, the recent spike in petroleum product prices is already constraining carbon emissions as the public reduces fuel use. A $1/gal increase in the price of gasoline is roughly equivalent to a $100 increase in the cost per tonne of emitting CO2. “The price of jet fuel has risen by a similar amount, and the price of diesel by even more,” said EPRINC. The report calculates that price increases over the past year will reduce petroleum demand by 3% within a year and 20% over the long run. “Though rising population and per capita income will offset these reductions, price effects taken alone will reduce long-run CO2 emissions from the consumption of petroleum products by about a fifth or by roughly 500 million tonnes/year,” the report concluded.

Adverse effects

Sellers of carbon-based fuels can expect demand to fall off as consumers conserve on petroleum use and as substitute products enter the market. “These effects will come on top of those from recent increases in petroleum prices, which already are motivating conservation and the development of substitutes,” EPRINC reported. The initial price increase has been estimated at 20-60¢/gal, but with fewer allowances each year relative to fossil fuel demand, the price increase is likely to become larger.

If the 5.2 billion initial allowances under bill S.2191 sold for $40 each, they would yield more than $200 billion in 2012. “Though the number of allowances would decrease over time, the per-allowance price likely would rise as they became scarcer so that this initial total might well substantially understate future annual amounts,” said EPRINC.

Refiners would pay more for the energy used to process crude, and transport costs would increase to refiners, pipeline companies, jobbers, and distributors of heating oil and LPG.

“The cost of processing chemical feedstocks into finished product would increase as would the cost of power, particularly in areas where coal is a major feedstock for generation,” the report said.

Energy companies likely would not be able to pass through all of the increase, particularly if competing with foreign firms not subject to GHG controls. Refineries operating in Asian countries that have not agreed to constrain GHGs would gain competitive advantage from a US cap and trade program.

In addition, a cap and trade system probably would trigger energy price volatility, adversely affecting demand and hindering investment. “At minimum, even if the economy transitions smoothly to less carbon intensive forms of energy, a cap and trade program will impose a ‘tax’ on energy consumers that may well exceed $100 billion/year. If S.2191 is an indication, none of the monies raised by a cap and trade system would be returned directly to taxpayers and little if any to consumers. A ‘tax’ of that magnitude starting in 2012 and likely rising after that could have considerable adverse effect on aggregate economic activity and hence on energy demand.”

Though the ultimate structure of a cap and trade system is yet to be determined, petroleum companies may be required to secure allowances not only for the carbon that they themselves emit but also for that emitted when their products are combusted. Since transport constitutes about 28% of all US GHG, this means petroleum firms would be required to submit about that percentage of the annual allowances issued.

Many cap and trade proposals would allocate only a fraction of allowances to private sector firms, with the fraction diminishing with time. Thus, it is unlikely that petroleum firms would be freely allocated as many allowances as the emissions they would be held responsible for. Indeed, in some cases such as the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative in which a number of northeastern states are participating, 100% of allowances will be allocated through auction, EPRINC reported.

Under cap and trade, petroleum firms will have to monitor the emissions for which they are responsible as well as their numbers of allowances to be sure they comply with the law. Assuming that banking and borrowing are a part of a cap and trade program, strategic management of the use of allowances over time would be important. This would require auditing emissions of each firm as well as managing its allowance accounts. Because the price of allowances may be volatile, firms might want to hedge via forward purchases or other contractual mechanisms. “In short, management of allowances is likely to be a major activity at larger petroleum firms, said EPRINC. The government would be responsible for the distribution of emission rights and would have to police emissions, allowances, and offsets.

The economic impact depends on how tightly the system constrains fossil fuel use relative to demand and how rapidly inexpensive sources of energy and of energy efficiency enter the market. In 2012, the first year of the program, GHG emissions from fossil fuels would have to be reduced 14% relative to baseline, with reductions escalating rapidly after that.

Opportunities

“Under cap and trade, allowances to emit carbon have value and hence are a potential source of wealth to the private sector,” said EPRINC. “There are several means whereby petroleum firms may be able to take advantage of opportunities to acquire a portion of this wealth. The most obvious is by securing free rights to allowances. Virtually all of the Congressional proposals freely allocate substantial proportions of the annual allowances to the private sector, though usually these proportions diminish over time as more of the allowances are auctioned.”

Petroleum firms will be forced to compete with other industries for free allowances. However, EPRINC said, “One criterion for awarding them likely will be historical emissions, and petroleum firms can qualify for allowances via this route.” The report said, “If a firm can both obtain free allowances and fully pass through its increased costs of energy, it can obtain a ‘windfall.’ More likely, it will not fully pass through all of its cost increase, and the free allowances are a form of compensation.”

Another method would be to create offsets at less cost than the price of allowances in the US market. “For example, a petroleum firm might sponsor the planting of trees under the Joint Development Mechanism in a developing country and receive sufficient credits to more than cover the costs,” said EPRINC. “Under several of the Congressional proposals, opportunities to obtain such net savings also might be possible working with US agricultural interests.”

A third possibility would be to obtain allowances in one year and sell them for a higher price in another. “Organized allowance markets already exist in the US and elsewhere, and with cap and trade these markets would greatly expand. Many firms probably would mainly use such markets to hedge against future allowance price changes, but if allowances rose in price over time, it would be possible to generate offsets in one year, sell them at a later time, and profit thereby,” EPRINC advised. “More generally, adroit management of allowances and of participation in allowance markets may provide a means for petroleum firms to profit. Given the numbers of allowances that some of the firms likely would have to deal with on an annual basis, investment in allowance market expertise may well prove worthwhile.”

It said, “One almost certain result of constrained carbon emissions will be to change the relative prices of fuels, with higher carbon content fuels becoming relatively more costly to produce and sell, and lower carbon fuels less so. Under these changed conditions, petroleum firms likely will experience greater relative demand for lower carbon fuels, especially natural gas in the power sector and possibly also in the industrial sector. Sales of LPG too may be relatively encouraged.”

If a portion of carbon allowances are auctioned, it will generate substantial revenues for the federal government. “Proposals to date have earmarked these funds for utilities, states, alternative energy R&D and deployment, and other climate-related purposes,” EPRINC reported. “Petroleum firms engaged in alternative fuel markets may receive benefits from some of the spending in the form of technology development and larger and more rapidly expanding sales opportunities.”

Carbon tax

In addition to cap and trade, two other policies have been proposed: command and control; and taxation. A carbon tax would be “a socially superior alternative” to cap and trade for constraining GHG. “However, its relative impact on petroleum firms is mixed. If proceeds from a carbon tax were used to reduce other taxes, particularly corporate income taxes, petroleum firms would share in the benefit,” said EPRINC.

No free allowances would be available under a tax approach. “Thus, a tax would avoid many of the problems of cap and trade, but it would negate opportunities to profit from such a system as well,” EPRINC said.

If some of the government’s proceeds from sale of allowances were used to subsidize alternative transportation fuels, it might have further adverse effects on petroleum markets. However, some energy companies could benefit from government spending of tax revenues on development of alternative energy sources.

Economists generally support a carbon tax as the best means to deal with CO2 emissions since it would be less costly to administer and would lead to less volatile energy prices. Revenues from such a tax could be redistributed to taxpayers via reductions in social security or income taxes. Such refashioning of the tax system would yield net gains to the economy, they claim.

If proceeds from a carbon tax were used to reduce other taxes, particularly corporate income taxes, petroleum firms would share in the benefit. Economists at the American Enterprise Institute estimated a tax of $10/tonne of CO2 would provide enough revenue to reduce the corporate income tax rate by 20% or income taxes by 6-7%. According to its analysis, such a tax also would reduce US GHG by 7.5%, EPRINC said.

“In addition, a carbon tax would avoid many of the administrative and monitoring issues imposed by cap and trade, and might be easier for firms to adjust to.”

The report said, “A carbon tax also has the advantage of making clear to the public what is being done. Cap and trade as presently formulated in Senate or House legislation gets at carbon reduction through what is essentially a very large tax and spending initiative but is not easily understood as such. The public is ‘taxed’ through the higher prices it would pay for fossil energy, with the revenues distributed to states, agricultural interests, private firms, and others via access to free allowances, or if raised through allowance auction then spent on a variety of climate-related programs. None of the leading legislative initiatives would recycle allowance-related monies back to the public in the form of reduced taxes.”

Nevertheless, most members of Congress are leaning toward cap and trade, which has broad support within the environmental community and some within the business community.

Energy efficiency

Command and control also will be part of the mix. “For example, the Senate and House enacted legislation in December 2007 (the Energy Independence and Security Act or EISA) that mandates an increase in CAFE to 35 mpg by 2020. The Department of Transportation, which is charged with implementing the law, recently proposed standards for passenger autos and light trucks under which their combined average fuel economy would reach 31.6 mpg by 2015. One major reason for imposing this constraint is to reduce emissions of CO2 from motor vehicles,” EPRINC reported.

“EISA also mandates vast increases in the use of ethanol, justified in part by projected reductions in GHGs. California has sought to impose a CO2 standard on vehicles sold in that state, but EPA recently turned down its request for an exception to do so, and the matter is currently in the courts.

“California also plans to impose a Low Carbon Fuel Standard, which would compel sellers of motor fuels in that state to steadily decrease the life-cycle carbon content of the fuels they sell. A form of such a fuel standard also was included in a recent climate change bill passed by the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee.

“Many in Congress would impose a nationwide Renewable Fuel Standard on suppliers of electricity, but such an initiative recently was filibustered in Senate consideration of EISA and excluded from the final legislation. Some states have adopted such standards, however.

“Finally, Congress has mandated home appliance energy efficiency standards and building standards, largely to reduce GHG emissions,” EPRINC said.