COMMENT: Obstacles bedevil EISA’s RFS biofuels mandate

Is it possible for 36 billion gal/year of renewable fuels to be produced in 15 years, and if so, would it bring energy independence and security to the US?

In this election year, the public is being offered numerous solutions to the energy problems that the US and the world must address.

One such proposal being actively promoted is to replace transportation fuels refined from imported oil with fuels such as biodiesel, bioethanol, and other advanced biofuels.

Often presented in the popular media and in political discourse is the notion that one of the most effective strategies to reduce our national dependence on imported oil is to have large quantities of biofuels produced from things that grow, and that somehow the private sector will embrace this strategy and produce all of the renewable fuels that will be needed.

The latest buzz is about using waste materials instead of food crops, because soaring corn prices have distorted the prices we pay for food as well as for corn ethanol.

The public is being told this second generation of biofuels could be produced from agriwaste, such as corn stover and wheat straw; from fast-growing cellulosic crops, such as switch grass; from forest residue and other wood waste; and from municipal solid waste retrieved from land fills.

Unfortunately, not being mentioned are the impracticalities of producing large quantities of fuels from these materials. Not being addressed are other impediments, such as bringing together the varied and often competing interests into biofuels projects, the technological hurdles that must be overcome, the vast amount of capital investment that will be needed, and the incentives the public will need to create a new industry.

For the last several years our company has been assisting clients in the development of biofuels projects. It is dismaying that the realities encountered in developing renewable biofuels are often not even mentioned, let alone discussed. Assumptions upon which so much hope is being placed are often wrong or shortsighted.

The latest example of oversimplification is the presumption built into the Renewable Fuels Standards (RFS), which is a component of the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (EISA). RFS is a legislative mandate requiring increased national production of renewable biofuelsto 36 billion gal/year by 2022 from 9 billion gal/year in 2008 without addressing how this can be done. It therefore is in serious need of a reality check.

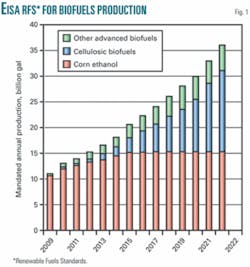

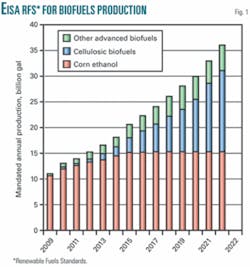

As shown in Fig. 1, the RFS mandates that US corn ethanol production reach a production peak by 2015 and not increase thereafter. This will require that cellulosic biofuel and all other advanced biofuels play a larger role in meeting the RFS mandate, increasing to 58% of the total RFS mandate by 2022 from less than 1% today, with corn ethanol dropping from its current 99% of the total to 42% in 15 years (Fig. 2).

The fundamental question that one must ask is whether it is reasonable to assume that EISA’s RFS mandate for the private sector is realistic. Based on what is known today, it is not. If nothing is done to assist the private sector, a mandated 36 billion gal/year of renewable fuels within 15 years is wishful thinking. There may be a chance that this could happen but only if extensive, costly government support programs are put into place.

What is likely?

Although EISA may have accurately projected a need for 36 billion gal of renewable biofuels by 2022, its dependence on private enterprise to fill this need is unrealistic for several reasons:

• The renewable fuels industry is fragmented, with only modest participation by large corporate interests.

Biodiesel currently is being produced from soybean oil in 20 biodiesel processing plants, owned by small corporations. A recent National Biodiesel Board survey indicated that a number of small biodiesel companies were raising equity for about 30 new biodiesel plants. Soybean oil used by these plants is obtained from 60 crushing plants in 21 states. Outside of a few growers’ cooperatives, ownership is concentrated with major agribusiness giants, such as Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge, and Cargill.

These crushing operations obtain soybeans from local soybean growers’ cooperatives. There are more than 300,000 farms in the US that grow soybeans on 75 million acres, most of them alternating with corn in a 50:50 rotation. About 75% of the soybean crop is grown in the Upper Midwest and Midwest, with the balance coming from the Southeast and Southwest. Crushers in these regions produce about 75% of the soybean oil and soybean meal. Vegetable oil produced from other oilseed crops such as canola is not now being used in making biodiesel.

Outside of a few small cellulosic ethanol plants that are just becoming operational on a commercial scale, all of the fuel ethanol is now being produced in 160 corn ethanol processing plants. As with biodiesel, most of these processing plants are operating in the Corn Belt states and are owned by small companies or growers’ cooperatives. The companies active in developing cellulosic ethanol plants also are mostly small companies. But a few major oil companies and paper companies are now participating in cellulosic ethanol development projects.

• With the exception of processes now used to convert cornstarch into ethanol, technologies for producing advanced renewable fuels are still in the research and development or pilot plant stage.

• There are only a handful of plants currently being developed to produce cellulosic ethanol on a commercial scale. One is a plant in Japan that has been producing commercial quantities of cellulosic ethanol from wood chips and wood waste for the past 2 years. Another is a project, well under way, in which a paper mill is being converted into a biofuels production facility using wood chips and black liquor as feedstock.

In addition, two funded projects are emerging from pilot operations and are being scaled up to produce cellulosic ethanol from municipal solid waste. And there is an exciting project under way in which a 2-stage thermal process is being used to convert forest residue and wood waste into cellulosic ethanol on a commercial scale.

However, there is still a long way to go before the RFS mandate can be met, as additional R&D of biofuels processes remain in progress to perfect and improve process efficiency, obtain higher biofuels yields, and make a wider range of advanced biofuels from the cellulosic waste.

Enormous investment

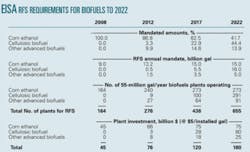

To meet the RFS mandate, capital investment in advanced biofuels plants must reach $11 billion in 4 years, increasing to $46 billion in 10 years and $105 billion in 15 years. Added to these amounts is the capital cost of increasing corn ethanol output to the 15 billion gal/year level at an added capital cost of $75 billion. In other words, the RFS mandate calls for private capital investment in renewable fuels plant capacity of $180 billion over the next 15 years (see table).

Added to this are the additional amounts that must be invested to improve the technology, provide supporting pipelines and storage terminal capacity, and upgrade distribution facilities to handle new fuels. Clearly, all of this private investment is just not going to happen as a result of a legislative mandate.

With respect to RFS projections, it may be realistic to expect corn ethanol production to increase to 15 billion gal/year over the next 10 years from 9 billion gal/year, assuming that current support programs remain in effect and corn crops are increased without further market distortion.

But it is unrealistic to assume that the RFS projections for advanced biofuels production could match corn ethanol production in 10-15 years. Cellulosic ethanol and biodiesel production is now just a “drop in the bucket.” In 4 years, the RFS mandate calls for 2 billion gal of cellulosic biofuel, biodiesel, and other advanced biofuels to be produced, increasing to 9 billion gal 10 years from now, and 21 billion gal 15 years from now.

This growth in advanced biofuels production will require at least 35 new 55-million gal/year biofuels plants to be operating by 2012, 164 by 2017, and 382 by 2022. New capital investment in advanced biofuels plants of this size could exceed $11 billion by 2012 and require an additional $34 billion by 2017 and $59 billion more by 2022. EISA does not provide funding or incentives for this massive investment it is mandating.

Barriers to investment

Further, there are a number of perceived or actual barriers to attracting the amount of investment needed to this infant industry:

- The market for new advanced biofuels, such as butanol and dimethyl ether as gasoline replacements, face market resistance. In the case of recently introduced biofuels such as biodiesel and E85, the oil industry is still not fully convinced that it should be making substantial investments that will be required in building biofuels processing plants, in establishing new biofuels distribution networks, or in undertaking new biofuels marketing campaigns.

- Growers of soybeans have not yet been convinced to abandon wheat or corn as a second crop in order to produce canola or other oil seed crops in the hope that biodiesel producers will expand and create a demand for vegetable oil that does not now exist. Likewise, crushers are reluctant to increase capacity to support yet-to-be-planted oilseed crops or to produce vegetable oil for yet-to-be-built biodiesel plants.

- Grain elevator operators and farm cooperatives that generate large quantities of agricultural waste are not eager to organize and invest in joint ventures for collection, preprocessing, and storage operations in anticipation of attracting investors to build new agriwaste-to-ethanol plants,

- Pulp and paper mills that have access to large amounts of pulp wood and wood waste are not fully convinced that they should produce cellulosic ethanol or other advanced fuels, as they have never been in the fuels business. They also are reluctant to upset the cost they now pay for wood and wood waste, or to modify their pulp mill operations if it could in any way adversely impact their paper-making operations.

- And no one is running out to build biofuels plants at a cost of $125-275 million each.

Other problems with RFS

The RFS mandate does little to meet EISA’s legislative goal of providing energy independence and energy security, as the 36 billion gal/year renewable fuel target is designed to provide less than 6% of the nation’s transportation fuel needs in 15 years.

Nor does the RFS mandate do much to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Today, corn ethanol is the dominant renewable biofuel.

The most optimistic assessment is that corn ethanol reduces greenhouse gasses by only 20% compared with conventional fuels. And even though cellulosic ethanol and other advanced biofuels offer higher reductions (50-60%), these fuels will not be produced in significant quantities for years, even if the RFS mandate is met.

At best, advanced biofuels are expected to be 13.2% of all renewable fuels produced in 2012, increasing to 37.5% in 2017 and 58.3% in 2022. This is only 3.5% of all transportation fuels to be consumed in the US in 2022.

On top of the other deficiencies associated with EISA, the RFS mandate is probably not enforceable, as the mechanism for enforcing it is weak and ill-defined. The responsibility for seeing that mandates are met is left to the US Environmental Protection Agency administrator, who has to negotiate with state governments…and grant exceptions when mandates prove impossible to meet.

At best, EISA provides political cover to politicians. The added biofuels to be produced under the RFS mandates would be only a small part of the energy independence solution EISA seeks to address.

Costly government aid

What could the government do other than a mandate? Meeting the RFS mandates would require a combination of extensive added government aid in the form of R&D grants, tariff protections, low-cost project financing, and loan guarantees to stimulate private investment in biofuels plants and ancillary facilities.

In addition, the government would have to provide tax incentives for biofuels operators during ramp-up and possibly price subsidies and other measures.

The author

Tim Sklar ([email protected]) is president of Sklar & Associates, a consulting firm specializing in biofuels project development. He is a CPA with expertise in project finance, due diligence investigations, viability assessments, and business plans. He has extensive consulting and operational experience in business turnarounds and operational management and restructuring, having served on the management consulting division of accounting and consulting firms PriceWaterhouseCoopers and KPMG on US and international assignments. Sklar served as chief financial officer of regional manufacturer GFC Inc, leading a major business turnaround effort.

He has held positions in the federal government as research director of a presidential commission charged with developing policy recommendations on educational finance reform and as director of regulatory enforcement in the Federal Energy Administration. Sklar has developed courses for CPAs and attorneys on due diligence for acquisitions and sales of closely held companies, high risk ventures, and emerging growth companies. He also provides liaison services for project sponsors, private investors, and concessionaires in dealings with international institutional lenders such as the World Bank, IDB, Ex-Im Bank, and OPIC.

Energy project experience includes petroleum refineries, power plants, power distribution systems, hybrid remote power generation systems, integrated oil seed crushing-biodiesel processing plants, and integrated pulp mill-cellulosic ethanol processing plants.