DECOMMISSIONING-2: Past contamination, future land use set abandonment time line

Historical contamination and future land-use plans for an abandoned pipeline location and its facilities can significantly affect the time line of leave-to-abandon proceedings.

Part 1 of this article provided an overview of Canada’s National Energy Board’s regulatory requirements and responsibilities with respect to pipeline abandonment, typical environmental issues associated with pipeline abandonment, and types and examples of pipeline abandonment addressed by NEB prior to the Yukon Pipeline Ltd. (YPL) case.

Part 2 of the series, presented here, provides a detailed case study of the abandonment and remediation of the YPL pipeline and its pump stations. The article’s conclusion will look at abandonment and remediation of the line’s tank farm and discuss the practical lessons that can be drawn from the YPL abandonment.

History

In 1942, the US army constructed a 114-mm (4.5-in) OD above-grade pipeline (Canol No. 2) from Whitehorse, Yukon, to Skagway, Alas. This pipeline, a tank farm in Whitehorse (the Upper Tank Farm or UTF), and a pump station at Carcross, Yukon, comprised part of the larger Canol pipeline project, constructed to transport, refine, and distribute liquid hydrocarbons from Norman Wells, NWT, for use in the Yukon and Alaska during World War II. The US army owned and initially operated the facilities.

White Pass and Yukon Corp. Ltd. (White Pass) began operating Canol No. 2 in 1947, reversing the flow to supply Whitehorse and the Yukon with gasoline, diesel, and fuel oil shipped by sea to Skagway from Vancouver, BC. In 1949, the US army resumed operating the pipeline, transporting White Pass fuels as well as their own.

White Pass purchased Canol No. 2 from the US and Canadian governments in transactions from 1958 to 1961 and became the sole shipper via the pipeline. In 1962, the newly formed National Energy Board granted YPL (a wholly owned subsidiary of White Pass) Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity OC-12 to operate the existing pipeline system consisting of the Canadian portion of the former Canol No. 2, the Carcross Pump Station, and the Whitehorse UTF.

YPL operated the UTF and Canadian portion of the pipeline from 1962 until 1994 with only minor modifications. Other wholly owned subsidiaries of White Pass operated the US section of the pipeline and related facilities in Skagway.

YPL apparently used the Carcross facility as a booster station until 1974, after which all pumping was conducted from Skagway.

Effective Oct. 7, 1994, YPL and related companies discontinued operations on the pipeline between Skagway and Whitehorse, and at the UTF. YPL said that the aging pipeline system was no longer economically feasible to operate and that the cost of upgrading the facilities to meet current regulatory requirements could not be justified. With new or improved highways in the area, trucking fuel to Whitehorse became more economical than transporting it via the YPL pipeline.

A series of inspections and communications during 1994 also saw White Pass served with a Hazardous Facility Order by the US Office of Pipeline Safety in February 1995. The order stated that continued operation of the pipeline from Skagway to the US-Canada border was “hazardous to life, property, or the environment” and that White Pass must complete hydrostatic testing within 120 days or physically abandon the pipeline within 60 days (subsequently extended to June 15, 1995).

In January 1995, YPL notified NEB that the pipeline had been depressurized and that the UTF was being drained. In May 1995, NEB staff inspected the YPL facilities and YPL began pigging the pipeline to remove fuel and clean the pipe interior. Effective June 1, 1995, White Pass sold its petroleum distribution assets.1 2

Regulatory process

In July 1995, pursuant to Paragraph 74(1)(d) of the NEB Act, YPL formally submitted its application to abandon its NEB-regulated facilities. NEB subsequently requested comments and advice from the public and regulators, and corresponded with YPL regarding further information requirements. Meanwhile, YPL commenced environmental site assessments (ESAs) of its facilities. In June 1996, YPL requested permission to remove the aboveground storage tanks (ASTs) from the UTF so that they could proceed with further ESA work. In response, NEB issued Hearing Order MH-3-96 to call a public hearing in accordance with Section 24 of the NEB Act.

NEB held the hearing in Whitehorse on Aug. 20, 1996. Registered intervenors for the hearing included the Hillcrest Community Association, the Yukon Conservation Society, Environment Canada, Transport Canada, the City of Whitehorse, the Yukon Territorial Government (YTG), and the BC Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks (MELP). All actively participated, with the exception of BC MELP, which indicated that it had already had its concerns satisfactorily addressed. Canadian Heritage, Health and Welfare Canada, the US Department of Transport (Office of Pipeline Safety), Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, and a local contractor provided letters of comment.

No one contested the pipeline abandonment. The hearing, therefore, focused on how the pipeline would be dismantled, how historical contamination would be addressed, and whether YPL had sufficient financial resources to properly abandon the pipeline system (NEB was satisfied that it did). Participants also discussed the potential for future residential development at the UTF and the concept of risk-based remediation.

Understanding of subsurface conditions and the extent of soil or groundwater contamination was still very limited at the time of the hearing and no one had yet identified the presence of phase-separated liquid hydrocarbons on the groundwater table at the UTF and Carcross. YPL had performed a Phase I (nonintrusive) ESA and a limited initial Phase II (intrusive) ESA at the UTF. Only a Phase 1 ESA had been performed on the pipeline right-of-way. Access issues prevented performance of an ESA at the Carcross Pump Station.

NEB determined, pursuant to Paragraph 20(1)(a) of the CEA Act, that, taking into account the implementation of YPL’s proposed mitigation measures and those set out in the leave-to-abandon order, the proposed pipeline abandonment was not likely to cause significant adverse environmental effects. NEB then issued order MO-7-96 granting YPL leave to abandon the pipeline and enabling YPL to begin dismantling the system and proceed with additional ESAs.

Pursuant to Subsection 19(1) of the NEB Act, however, NEB delayed the date that formal leave-to-abandon status would come into force until YPL fulfilled a number of conditions. Among other things, YPL was to complete and report on the outstanding Phase I and II ESAs, plan and conduct appropriate remedial work, and file a final report demonstrating the success of the remedial work. NEB also required YPL to “provide information to and consider the comments of any persons who indicate to YPL that they wish to be consulted.”1-3

Environmental setting

The YPL pipeline ran 144.5 km from the US border at White Pass Summit (near Fraser, BC) through Carcross and north to Whitehorse. The US Army, driven by war-time expediency, constructed the majority of the pipeline on grade within the right-of-way of the White Pass and Yukon Route railway (WP&YR, at the time was also owned by White Pass). Where it deviated from the railway right-of-way closer to Whitehorse, the Canadian government sold the pipeline to YPL with its own 30-m right-of-way, but YPL never received official title to the land.

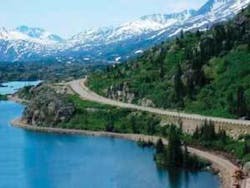

Including 52.3 km in BC and 92.2 km in the Yukon, the pipeline and railway traversed a variety of generally sparsely populated, sometimes sandy but more frequently marshy or rocky terrain, crossing many creeks and following the shorelines of numerous water bodies, including 26 km along the shore of Bennett Lake south of Carcross (Fig. 1) and 4 km along the shores of Shallow Lake and Bernard Lake near Fraser (Fig. 2).1

The pipeline’s general position on grade adjacent to the railway, roads, and rock cuts (particularly in the more mountainous terrain toward the southern end of the pipeline) exposed it to potential third-party and natural damage.

Some segments lay below grade. This occurred:

The pipeline had no cathodic protection and was substantially uncoated, and was therefore susceptible to corrosion where it was buried, under water, or in contact with wet ground.1-3 These factors contributed to numerous product releases along the right-of-way during the pipeline’s operating history.

Abandonment, mitigation

YPL pigged the pipeline prior to the abandonment hearing to remove remaining product and clean the interior of the pipe. Compressed air propelled a squeegee-type pig from the highest point on the pipeline toward Skagway, and then from the same point toward Whitehorse. The pig passed through the line up to three times. YPL disconnected the pipeline at the valve locations, installed taps at low points on the pipeline to drain any trapped product, and then visually inspected the interior of the pipe and tested for organic vapors to ensure it was clean.

YPL committed to remove most of the pipeline; it being generally above-grade and easily accessible by rail or road. Removal required cutting the pipe into manageable lengths, lifting it by crane onto a rail car or truck bed, and transporting it offsite for reuse or recycling. Plans called for pipe buried under a thin layer of rail ballast or fill to be hand-exposed at regular intervals, cut, and lifted straight out of the ground, avoiding contact with vegetation. Restoration included hand-raking the disturbed soil back into place and revegetating the area, as required.

Removing pipe from standing water or wetlands required it be cut, tested, and plugged where it entered and exited the wet area, and then pulled out of the area from one end. A 2-km section in a wetland near Cowley Lake, Yukon, called for removal in winter to minimize disturbance of the wetland.

Pipeline buried under roads or railways needed to be filled with an inert material and abandoned in place.

A qualified contractor, in accordance with applicable regulations and guidelines, was to conduct pipeline removal, with removal in environmentally sensitive areas to be monitored by a qualified professional. The timing of work was to minimize effects on wildlife. Unstable slopes were not to be disturbed and silt fences were to be used where appropriate. Crews carried spill cleanup material for quick response in event of a release.1-3

During pipeline removal, YPL collected soil samples every 100 m along the pipeline for visual observation and organic vapor monitoring. The company attributed two hydrocarbon-affected areas to rail activity to be addressed by WP&YR.4

NEB staff inspected the pipeline right-of-way in June 2005 and observed that the majority of the pipeline had been removed. Cut ends of sections abandoned in place were welded closed. A linear indentation was still visible in some areas where the pipe had rested directly on the ground.

Assessment, remediation

YPL took a qualitative risk-based approach to identify areas of potential environmental concern (APECs) during a Phase I ESA of the pipeline right-of-way. YPL conducted a reconnaissance of the entire right-of-way, looking for visual evidence of contamination and assessing each recorded spill based on the age of the spill, season during which the spill occurred, hydrogeology of the site, and distance to receptors. As a result of this assessment, five APECs were identified on the right-of-way.5

Phase II ESAs of the APECs on the right-of-way included soil vapour surveys and test hole excavations, as well as borehole drilling and monitoring well installation where the potential for groundwater contamination was identified. YPL also collected water samples from private drinking water wells within 300 m of the right-of-way. YPL compared analytical results for soil within or adjacent to road or railway right-of-ways with Yukon Contaminated Sites Regulations (CSR) and CCME criteria for industrial land use. It compared groundwater samples with CSR and CCME drinking water criteria. Groundwater samples from monitoring wells were also compared with CSR and CCME freshwater aquatic life (FAL) criteria. Two APECs required remediation.6

In situ bioremediation addressed one APEC, while excavation and land farming dealt with the other. Confirmatory soil and groundwater samples met Yukon CSR industrial land use, FAL, and drinking water criteria, except for one minor exceedence of the soil criteria, which YPL expects to naturally attenuate.4 7

Pump station

The Carcross pump station sits on the north edge of the village of Carcross, about 370 m northeast of Bennett Lake. Located on the edge of the Carcross Desert, the 8.3 hectare site is well drained, with rolling sandy hills vegetated by scattered stands of pine and poplar trees (Fig. 3). The water table is 6 m to 16 m below grade and flows principally toward Bennett Lake to the southwest. Adjacent land to the northwest and southwest is undeveloped, while the northeast edge of the property is bounded by the railway right-of-way. There is residential land use to the south and commercial land use (including a gas station) about 300 m to the south-southeast.

Facilities on the site in 1996 included an empty and disconnected 1,600 cu m cylindrical AST, yard piping, foundations of the dismantled pump station and maintenance shop (including a mechanic’s pit), stored pipe and pipeline components, barrels, and other refuse. Previous facilities included two additional 1,600 cu m cylindrical ASTs, four ellipsoidal ASTs, a filter house, barrel filling shelter, and tanker truck loading rack. The railway owns the land.

Tank cleaning involved removal of all solid, liquid, and vapor phase product, venting the tank to atmosphere, and placing grates over access ports to prevent unauthorized entry. Resulting wastes were to be handled in accordance with Yukon Special Waste Regulations.

A qualified contractor was to conduct tank dismantling and removal in accordance with applicable regulations and guidelines, with scrap metal transported offsite for recycling.1

In contrast to the right-of-way, YPL conducted relatively standard Phase I and Phase II ESAs at the Carcross station. The company reviewed historical records, interviewed former YPL employees, and conducted a sight reconnaissance. It then performed soil vapor surveys, test hole excavation, drilling, monitoring well installation, and soil and groundwater sampling (including sampling of nearby private drinking water wells). YPL also consulted old drawings and conducted a geophysical survey to identify and locate potential buried yard piping for removal.

Elevated subsurface vapor occurred in the immediate vicinity of both onsite cylindrical ASTs (particularly the one recently removed) and the maintenance shop. Phase-separated liquid hydrocarbons up to an apparent thickness of 1.1 m were present on the groundwater surface in two monitoring wells.

YPL compared analytical results with CSR and CCME criteria for industrial land use (soil), FAL (groundwater samples from monitoring wells), and drinking water (private water well samples), substantially delineating soil and groundwater effects onsite. The company determined that on site liquid and dissolved-phase hydrocarbon plumes were stable and immobile. YPL also stated that excessive off site, down-gradient groundwater levels originated from the off site AST. Hydrocarbons did not affect nearby private drinking water wells.8

Excavation and land farming addressed remediation of shallow affected soils (<3 m deep). Site-specific numerical standards (SSNSs) for soils deeper than 3 m below grade indicated that soils saturated with hydrocarbons could be left in place so long as phase-separated liquid hydrocarbons were not present.

A liquid hydrocarbon recovery program was initiated to deal with liquid and dissolved hydrocarbons.

YPL removed all identified yard piping from the site for recycling, and recovered liquids from inside the pipes for appropriate disposal. Confirmatory shallow soil samples met Yukon CSR industrial land use criteria, except for one minor instance which YPL expects to naturally attenuate.

Phase-separated liquid hydrocarbon recovery continues steadily (about 0.3 l./day as of May 2005) and dissolved hydrocarbon concentrations adjacent to the liquid plume remain in excess of Yukon CSR FAL criteria.7 9 10

Parties following the process requested and were provided with satisfactory details regarding the remediation methodologies.11 They also pointed out APECs not previously investigated by YPL, resulting in an expansion of the areas investigated and remediated.

The Carcross Pump Station property is currently vacant, zoned industrial, and owned by the railway. YPL asserts that “there are no plans to use or develop the site for any purpose other than a storage yard for rail materials”. As such, the human health receptor YPL used to calculate SSNSs was a teenaged trespasser on site for 1 hr/day, 365 days/year. Based on this scenario, YPL concluded that the site presents no human health risk in its current state.9 Abandonment of the site in its current status could, however, restrict future industrial development.

The SSNSs also fail to account for hydrocarbons moving from soil into groundwater. YPL has committed to meeting FAL criteria after completion of phase-separated liquid hydrocarbon recovery.8-9 It is not clear, however, whether the company can achieve FAL groundwater criteria so long as associated soil remains saturated with hydrocarbons.

Regardless, it may be a long time before YPL completes liquid hydrocarbon recovery. Recovery under way since 1998 shows little sign of abating. No-one knows how much product remains in the ground. Although it appears that the liquid and dissolved plumes are relatively stable, the size and behavior of these plumes are not well understood. YPL could consider more aggressive liquid hydrocarbon recovery techniques, but one might debate the justification for such measures given the lack of current plans to redevelop this land and the apparent lack of current risk it poses to human health or the local ecology.

The most powerful impetus to clean up the Carcross site may be the desire to achieve overall remediation of the pipeline system, thereby bringing leave-to-abandon into effect and allowing more marketable YPL assets, such as the UTF, to be redeveloped.

References

- NEB, “National Energy Board Order No. MH-3-96, White Pass Transportation Ltd. Yukon Pipeline Abandonment, Hearing held at Whitehorse, Yukon, 20 August 1996, Volume 1,” https://www.neb-one.gc.ca/ll-eng/livelink.exe/fetch/2000/90464/90552/92272/92808/92809/MH-3-96_Volume_01.pdf?nodeid=92811&vernum=0, and referenced exhibits, August 1996.

- NEB, “Reasons for Decision, Yukon Pipelines Limited MH-3-96, Facilities Abandonment,” https://www.neb-one.gc.ca/ll-eng/livelink.exe/fetch/2000/90464/90552/92272/92808/92810/1996-09-01_Reasons_for_Decision_MH-3-96.pdf?nodeid=92817&vernum=0, September 1996.

- NEB, “Environmental Screening Report [for Yukon Pipelines Limited (“YPL”) Application to Abandon Pipeline Facilities],” August 1996.

- Golder Associates Ltd., “Report on Site Restoration, National Energy Board Order MO-7-96, Yukon Pipelines Limited, Pipeline right-of-Way, Yukon and British Columbia,” September 2001.

- Golder Associates Ltd., “Status Report on Environmental Site Assessment of the White Pass Petroleum Products Pipeline and Associated Infrastructure,” July 1996.

- Golder Associates Ltd.,“Report on Environmental Assessment and Plan of Restoration, Yukon Pipelines Limited, Pipeline right-of-Way,” February 1998.

- Golder Associates Ltd., “Board File No. 3400-Y001-2, Yukon Pipelines Limited, Leave to Abandon MO-7-96, Reply to NEB Letter Dated August 1, 2002,” January 2003.

- Golder Associates Ltd., “Phase 1 and Phase II Environmental Site Assessment and Plan of Restoration, Yukon Pipelines Ltd., Carcross Pump Station,” February 1998.

- Golder Associates Ltd., “Report on Site Restoration, National Energy Board Order MO-7-96, Yukon Pipelines Limited, Pump Station, Carcross Yukon,” September 2001.

- Golder Associates Ltd., “Yukon Pipelines Limited NEB Order MO-7-96,” September 2005.

- Golder Associates Ltd., “Plan of Restoration-Soil and Water Management Procedures for Excavation of Hydrocarbon Impacted Soil, Carcross Pump Station,” May 1998.