UNCONVENTIONAL GAS-Conclusion: Outlook sees resource growth during next decade

Modeling and analyses indicate that as long as natural gas prices do not fall dramatically unconventional gas production will continue to expand, particularly as investment in improved recovery technology continues and as new plays and prospects are developed.

As summarized in the first article in this series (OGJ, Sept, 5, 2007, p. 35), the US has seen a decade of progress in unconventional gas. Annual production from all three unconventional gas resource plays-tight gas sands, coalbed methane, and gas shales-reached in 2006 a record 24 bcfd and proved reserves at the beginning of 2006 were a record 105 tcf.

Today, two out of three wells in the US target these three natural gas resource plays.

Contrary to views by some that unconventional gas is merely a playground for small producers, today 9 of the 12 largest US natural gas fields produce unconventional gas. At the top of this list is the 3.8 bcfd produced from the Cretaceous-age tight gas and coalbed methane of the San Juan basin. Next in line is the 1.4 bcfd produced from the Barnett gas shales of Newark East field. A decade ago, these unconventional gas fields were either undeveloped or much further down the list in terms of size (Table 1).

EIA outlook

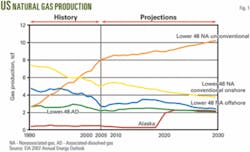

The US Energy Information Agency provides the official scorecard and projections for US oil and gas production. In its 2007 Annual Energy Outlook, EIA projects that unconventional natural gas production will continue to grow, from about 8 tcf/year in 2005, to 8.8 tcf/year in 2015 and to 10.2 tcf/year by 2030, accounting for more than half of US Lower 48 gas production (Fig. 1).

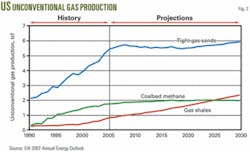

Fig. 2 provides a more disaggregate EIA outlook for each of the unconventional gas sources. This shows that EIA expects gas production from tight gas sands and coalbed methane to plateau in the next decade, with gas shales providing the great bulk of expected growth.

To assess the reliability of EIA’s outlook for unconventional gas production, we undertook two tasks. First, we used ARI’s unconventional gas data and modeling system (MUGS). Second, we examined 6 years of actual production data for unconventional gas and compared these data with past EIA projections.

The exercise with the MUGS model and its 93 distinct gas plays provides somewhat higher projections for unconventional gas production in the next decade than EIA, particularly for tight gas sands. As such, EIA’s projections may be somewhat conservative.

The reason is that MUGS provides a projection of potential natural gas production without some of the constraints included in EIA’s National Energy Modeling System (NEMS).

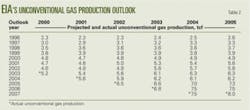

The actual performance of unconventional gas has consistently exceeded EIA’s projections in past Annual Energy Outlooks. Table 2 shows the projections through 2005 for unconventional gas in 12 Annual Energy Outlooks and compares these with the actual value. For example, the 1996 outlook projected that unconventional gas production would grow only modestly to 2.6 tcf by 2005. Four years later, with benefit of new data and an improved model, the 2000 outlook raised the 2005 production estimate to 5.6 tcf.

The actual unconventional gas production in 2005 was about 8.0 tcf, substantially exceeding both earlier projections. If history holds, EIA’s projections for unconventional gas production 10 years from now may, once again, turn out to be conservative.

Industry’s plans

Another way to gain insight on the outlook for unconventional gas is to look more closely at industry’s plans for unconventional gas and resource plays.

The majors are returning to unconventional gas.

ConocoPhillips, North America’s largest natural gas producer, greatly expanded its presence in unconventional gas with the acquisition of Burlington Resources Inc. With this acquisition, ConocoPhillips gained access to 1.2 bcfd of San Juan basin tight gas and coalbed methane production, plus significant undeveloped acreage in other resource plays.

ExxonMobil Corp. has established a large deep tight-gas prospect in the Piceance basin of Colorado that, according to company officials, “ultimately could yield about 35 tcf.”

Shell has under active development the tight gas sands at the Pinedale anticline in the Green River basin of Wyoming, already the fourth largest US natural gas field, with expectations of producing 0.5 bcfd from this area.

BP PLC, with large land holdings in Wyoming and Colorado, recently announced a $4.6 billion, 15-year development program to increase production from unconventional gas areas.

Large independents are increasing their already substantial investments in unconventional gas.

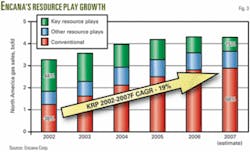

For EnCana Corp., North America’s second largest natural gas producer, has a growth strategy centered on unconventional gas resource plays, having already increased gas production from these key resource plays from 1.2 bcfd in 2002 to 2.7 bcfd, expected for 2007 (Fig. 3).

Anadarko Corp., North America’s sixth largest natural gas producer, has identified 1,000 tcf of future natural gas potential in North America, with 70% being unconventional gas (Fig. 4).

XTO Corp. has built significant positions in key unconventional gas plays, including the acquisition of Dominion’s tight sand and coalbed methane assets in the Rocky Mountain and South Texas regions. These actions have enabled XTO to increase its overall gas production from 0.5 bcfd in 2001 to an expected 1.8 bcfd in 2007. Tight gas accounts for 65%, gas shales for 17%, and coalbed methane for 10% of XTO’s overall natural gas production.

Midsize and smaller independents are making unconventional gas their core strategy.

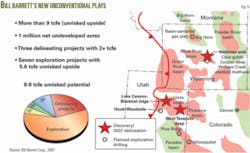

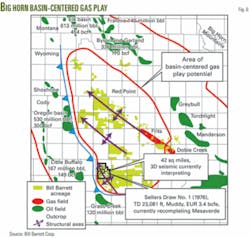

Bill Barrett Corp., formed in March 2002 after the sale of Barrett Resources to Williams Cos., has assembled a portfolio of unconventional gas and oil prospects with 8-10 tcf of unrisked exploration potential (Fig. 5). Barrett’s exploration prospects include testing the basin-centered tight gas sand play in the Big Horn basin, a basin whose resource potential has yet to be assessed by the USGS.

Southwestern Energy Co. has assembled about 900,000 acres in the Fayetteville gas shale play of the Arkoma basin. According to company officials, assuming development of 50% of the acreage at 80-acre spacing and 1.4 bcf/well, the play has a potential for 11 tcf of gross ultimate gas recovery.

Newfield Exploration Co. has acquired 400,000 acres in the Woodford gas shales of the western Arkoma basin, holding an anticipated upside of 3-6 tcf unbooked net recoverable resources.

Remaining resource economics

Numerous energy analysts and producers have asked how much the sharp rise in well drilling and completion costs and the decline in well productivity (reserves per well) have harmed the economic viability of unconventional gas.

With at least a pause in the rise in well costs, the key concern is the steep recent declines in well productivity. The first article in this series (OGJ, Sept, 5, 2007, p. 35) discusses this topic in more detail. A look at the mature San Juan basin, which has already produced 22 tcf of tight gas, serves as the example and provides useful insights.

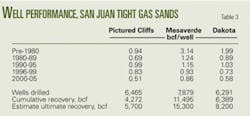

The 1990s had robust R&D and technology investment in unconventional gas and saw only modest declines in well productivity. As investment in unconventional gas R&D and technology were slashed in this decade, well productivity resumed its steep decline (Table 3).

The “silver lining” in this case study is that, with the persistent pursuit of efficiencies in well drilling and field operations, the unconventional gas industry has been able to continue to develop economically what would otherwise be marginally economic resources.

Based on our modeling and analyses, we find that, precluding a collapse in natural gas prices, unconventional gas can and will remain an economically viable or growing gas play, assuming three steps are taken:

1. Investments in improved recovery technology to stabilize the decline in well productivity.

2. Geologic and reservoir knowledge of emerging unconventional gas plays is improved, enabling this resource to be more intensively developed.

3. New resource assessments uncover the many still overlooked unconventional gas plays and prospects.

Priority

If unconventional gas is to remain economically viable in light of increasingly difficult reservoir environments, reserves per well must improve. The question is what will it take to achieve this objective?

In the authors’ view, as first priority, it will take major new investments in unconventional gas R&D and technology development, considerably beyond the levels of investments made so far in this decade. Imperfections exist in the R&D and technology investment marketplace, as set forth in the recent Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report.1 Overcoming these market imperfections will require a pooling of R&D investment resources and efforts, combined with effective transfer of technology.

Many insights and technologies being used to unlock unconventional gas were acquired from the extensive R&D and technology investments made by a partnership involving industry, the former Gas Research Institute, and the US Department of Energy in the 1990. These technologies included efficient multizone well completions for coalbed methane, hydraulic fracture mapping and diagnosis for tight gas sands, and horizontal wells for gas recovery from extremely low permeability gas shale.

With the formation of the new unconventional gas technology institute called RPSEA (Research Partnership for Securing Energy for America), there is a promise that the next decade should see similar accomplishments.

With improved technology, it will also become more feasible to pursue the second priority for unconventional gas-intensive resource development.

The intense infill development of the lenticular Mesaverde tight gas sands of the southern portion of the Piceance basin at Rulison field provides a most instructive case study.2 One section in this field (Section 20, T6S R94W) has been progressively downspaced from its initial 160 acres/well to the current 10 acres/well. As a result, this one section now will contribute 110 bcf of recoverable resource rather than only 8 bcf under the initial well spacing, as discussed in the second article in this series (OGJ, Sept. 17, 2007, p. 64).

The intensive vertical development of the Lance tight-gas formation in the northwestern portion of the Greater Green River basin at Jonah field provides a second instructive case study. Here the combination of more precise pay selection and intensive completion (often involving 20 or more frac stages and pay zones) now provide 5-10 bcf/well, up from 1-2 bcf/well with previous completion practices.

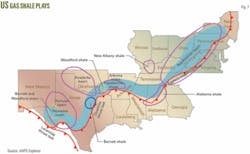

Third, the future of unconventional gas will rest on the successful pursuit of new, previously overlooked basins and plays, such as the tight-gas reservoir in the Columbia and Big Horn basins, (Fig. 6), and the numerous emerging gas-shale plays of the Mid-Continent, West Texas, and the Rockies (Fig. 7).

Massive resources also exist in the deep, high rank, coalbed methane in the Piceance, Uinta, and Greater Green River basins and shallow, lower rank, coalbed methane along the Gulf Coast. Again, economically unlocking these unconventional gas resources will require advances in technology.

Finally, the efficient and environmentally prudent development of unconventional gas will require supportive regulatory frameworks and public policies, particularly with respect to resource access and environmental stewardship. Industry and government will need to continue to collaborate to ensure that this critically important domestic resource can be developed, while also ensuring that the environment and other public interests are appropriately protected.

References

- “Evaluating the Role of Prices and R&D in Reducing Carbon Dioxide Emissions,” US Congressional Budget Office, September 2006.

- Kuuskraa, V.A., and Ammer, J., “Tight Gas Sands Development-How to Dramatically Improve Recovery Efficiency,” GasTIPS, Winter 2004.

- “US Crude Oil, Natural Gas, and Natural Gas Liquids Reserves 2005 Annual Report,” US DOE, Energy Information Administration, DOE/EIA-0216(2005), November 2006.