India faces challenges meeting gas, LNG import needs

This part of the special report on India’s changing energy balance assesses the growing role the importation of natural gas via pipelines and LNG can play in meeting India’s future energy demand. Part 1 of the article covered India’s energy market forecast, its gas price evolution, and the role indigenous gas supplies and equity in overseas supply sources will play in satisfying the country’s gas market growth (OGJ, Jan. 23, 2006, p. 18).

India’s gas industry is at a crossroads because demand is outpacing domestic production. Although passage of the New Exploration Licensing Policy has raised domestic gas prices and encouraged new exploration and development, domestic production alone will remain insufficient to meet rising domestic demand. Therefore, India must look for domestic gas supply alternatives such as gas imports.

However, the recent dispute between Russia and Ukraine, which resulted in interruption of gas deliveries to Ukraine and Europe, emphasized the importance of geopolitics in the management of imported energy (OGJ Online, Jan. 4, 2006). Although settled without much immediate damage to Russia’s gas customers, the confrontation underscored the role of geopolitics in cross-border gas movement and the importance of developing diversified sources to mitigate that risk.

To avoid exposure to such economic pressure, India is seeking gas from a variety of sources, including increased domestic production, key investments in oil and gas production in other countries, and gas imports. Among India’s import options are LNG, compressed natural gas (CNG), and imports through pipelines. Although such a strategy likely will cost the country more in the short term, it should lead to gas market stability over the longer period.

Pipeline options

All pipeline import options, which include bringing gas from Bangladesh, Iran, Myanmar, or Turkmenistan, rely on difficult negotiations with neighboring countries. Four major pipelines currently are under discussion:

- Bangladesh-India. Bangladesh is estimated to have 32-38 tcf of natural gas reserves-sufficient to meet its own domestic needs as well as markets in India. However, there has been continued popular opposition in Bangladesh to exporting its gas to India.

Export proposals repeatedly have been stalled by political action, and no resolution appears likely in the near future. If a pipeline from Bangladesh were constructed, it would be feasible to connect it to gas fields in India’s Tripura state and to neighboring Myanmar.

It appears, however, that exports from Bangladesh can occur only when all issues concerning reserves, domestic supply, and transit fees are resolved. - Myanmar-India. India and Myanmar are exploring proposals for delivering gas from sources off Myanmar to India via pipeline or other methods. A pipeline to India could either pass through Bangladesh or bypass it.

India intends to continue discussions with Bangladesh regarding transit fees and other terms. It also is investigating several more costly options, such as bypassing Bangladesh and avoiding the transit fees by shipping the gas subsea, shipping it onland through northeastern India, or delivering in the form of LNG or CNG shipments. Constructing a 1,400 km pipeline from Myanmar into the Indian states of Mizoram and Assam and connecting markets in India, for example, would roughly double the length of a pipeline through Bangladesh. - Iran-India. Proposals to bring gas from Iran to India have been discussed for more than 15 years. Iran could supply India either via a pipeline through Pakistan, an offshore pipeline bypassing Pakistan, or by shipping LNG. Gas would be sourced from South Pars field, which contains 8-10 tcf of gas reserves and lies just off Iran’s coast in the Persian Gulf.

Some analysts have indicated that gas could be imported for a delivered price of $3.35/MMbtu via one of these pipeline import options. With the thaw in India-Pakistan relations over the past 2 years, the project has gained some traction, but it is still under negotiation. Major concerns include pipeline financing and a host of geopolitical issues, such as the potential for destabilization of the peace between India and Pakistan and possible US trade sanctions on countries trading with Iran-an issue India must resolve before President George W. Bush’s visit to the country in March. - Turkmenistan-India. Turkmenistan also is a potential supplier to India. With more than 71 tcf of proven reserves in the country and limited domestic demand, the country has significant capacity for export and is seeking an alternative to exporting gas through Russia. Such a pipeline would transit Afghanistan and Pakistan, however, making it possibly the most politically challenging of the potential pipeline routes to India.

All these pipeline options remain speculative and face formidable geopolitical and commercial hurdles. It appears that none of them would come to fruition for several years.

LNG supplies

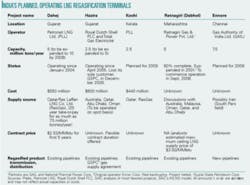

During the mid 1990s, India turned to LNG to meet its energy demand. More than 12 receiving and regasification terminals have been proposed at various times, but the list has been whittled down to five terminals. Two of them, at Dahej and Hazira in Gujarat, are already in operation (see table). In addition, Ratnagiri Gas and Power Pvt. Ltd. is constructing a terminal at Dabhol in Maharashtra, and active discussions are under way for two other terminals, Kochi and Ennore.

Petronet LNG-a private joint venture of state-owned Oil & Natural Gas Corp., Gas Authority of India Ltd. (GAIL), Indian Oil Corp., Gaz de France, Asian Development Bank, and other private investors-owns the Dahej terminal, which receives LNG from Qatar.

Royal Dutch Shell PLC’s LNG terminal at Hazira operates as a merchant terminal with the ability to enter into short-term as well as long-term supply contracts from multiple supply points rather than serving exclusively as a dedicated terminal with defined supply points for specific customers.

Because of higher international gas prices, Shell lost its sole dedicated customer, Gujarat State Petroleum Corp. (GSPC) in December, keeping the continued operation of the Hazira terminal in question (OGJ Online, Jan. 18, 2006). The terminal operated far below its capacity because buyers did not agree to pay international market prices for LNG. The terminal received a total of only three cargos for GSPC in 2005. Shell currently is engaging in discussions with other potential customers for LNG deliveries at Hazira.

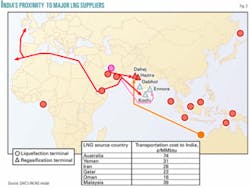

India, situated between the rapidly growing LNG importers to its east and the big OPEC exporters to its west, enjoys the advantage of reduced shipment costs to its ports. Because delivery distance impacts price, LNG terminals in India are most likely to receive their shipments from the nearest suppliers with direct shipping routes to India.

India’s terminals are most likely to be supplied, as is currently the case, from Qatar, UAE, or Oman to the west. Longer term, Iran also is poised to provide significant LNG supplies to India if it can come to terms on the geopolitical risk and price. LNG supply might also come from countries such as Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, or Australia to the east of India. Most other exporting countries in the Pacific Basin already have long-term contracts with importers.

Persian Gulf suppliers generally have a transportation advantage over Southeast Asia suppliers, which are further away and already have customers in Japan and potential new customers in China.

Australia is a potential supplier outside the Persian Gulf, and state-run GAIL is investing in Australian exploration, development, and liquefaction facilities to serve the Dabhol LNG terminal.

LNG trends, competition

Rising global demand for LNG-and its limited supply-are impacting LNG prices and trade patterns and likely will increase the price of LNG imports to India. This could pose problems for the country’s nascent LNG industry because manufacturers and power developers say that a price greater than $3-3.50/MMbtu would not be economically viable.

During the late 1990s, LNG appeared an attractive option. In Europe and Asia, LNG prices generally have been indexed to oil prices-attractive as long as oil prices remained below $25/bbl as they did for most of the decade. India could expect to import LNG at $2-2.50/MMbtu cif (cost, insurance, and freight). LNG suppliers thought of LNG markets in terms of long-term contracts with the product priced to cover costs and provide a reasonable return along the LNG value chain.

Market trends developed within the last 5 years, however, have prompted LNG suppliers to seek contracts with prices tied to netbacks received from other parts of the world. The resulting boost in overall LNG prices likely will severely curtail India’s LNG imports if the international market price for gas remains at current levels or higher.

In addition, LNG is facing increased competition from the development of new domestic gas discoveries-indigenous volumes that generally can be delivered at a lower cost than gas transported across the sea.

If gas is imported by pipeline from Iran, Bangladesh, or Myanmar, that also would constrain LNG imports. Other possible inhibitors to LNG growth include gas pricing policies in India and the availability of capital. Finally, India’s existing limited distribution infrastructure impacts the number of LNG terminals the country can currently support.

Other key global trends that could influence India’s LNG industry include:

- Emergence of the US as a growing LNG consumer, with LNG prices increasingly linked to US gas prices.

- Growth in European LNG imports to satisfy growing demand and replace dwindling supplies from the North Sea.

- Competing demands from China for LNG and other forms of energy.

- Expectations for continued high oil and gas prices.

Fig. 1 shows expected LNG regasification capacity additions through 2012 from Science Applications International Corp.’s World LNG (WLNG) database model. Atlantic Coast America (including Mexico) shows the biggest rise in annual import capacity, to more than 3 tcf/year by 2012. Most of the capacity likely will be added through new Gulf Coast terminals, although SAIC expects that one terminal could still be built to serve Florida and the US Northeast through Canada.

Also, expansions of existing terminals will add capacity. On the West Coast of the Americas, at least one and possibly two LNG terminals could be built, providing 700 bcf/year in additional import capacity.

Europe shows the next largest growth in LNG imports, adding 2.5 tcf/year of capacity to its existing 3 tcf/year capacity.

China, South Korea, and Taiwan could add as much as 1.7 tcf/year in import capacity over the next 7 years, while India and Southeast Asia could add as much as 500 bcf/year.

Location advantage

Growth in non-Indian regasification capacity is unlikely to have a significant impact on LNG trade to India, however, because of India’s proximity to Persian Gulf producers and its delivery cost advantage compared with the rest of the world.

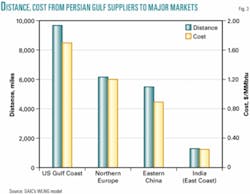

India is closest to almost 50% of the world’s LNG supply. Fig. 2 shows the proximity of India to major LNG exporting countries, particularly Persian Gulf suppliers. India’s delivery cost advantage should prevent netbacks from the Americas, Europe, and China from pricing it out of the market unless gas prices in Europe and the US remain continually above $5.50/MMbtu.

The distance from India to Middle East LNG suppliers is 1,300 miles, and the shipping cost of LNG is about 25¢/MMbtu, compared with Europe and China, which lie over 6,000 miles and 5,500 miles, respectively, from major Persian Gulf suppliers (Fig. 3).

Assuming a long-term price of $5/MMbtu (cif) in the US Gulf Coast-adjusting for liquefaction and regasification costs-Middle East suppliers, therefore, could as profitably receive $3/MMbtu (cif) for LNG supplies to India.

Acknowledgments

The authors prepared this article for information and discussion purposes only. The authors’ views and opinions do not necessarily reflect those of SAIC. Some insights in the article are drawn from research conducted at the Energy Resources Management and Policy program at the University of Maryland University College, where coauthor Shree Vikas also serves as an adjunct faculty member.