POINT OF VIEW: TransCanada pipeline president guides course to liquids, TAGP

As demand for hydrocarbons continues to rise, it becomes increasingly important not only that new sources of supply are found and developed, but also that the resulting production can be brought to market in a timely and efficient manner.

Transportation solutions are often integrated into the overall development plan for a new field and have direct bearing on the feasibility of developing otherwise marginal resources. Failure to effectively address transportation issues can lead to bottlenecks in development of projects otherwise deemed economically feasible (witness current efforts to move Arctic natural gas south from Alaska and Canada’s Mackenzie Valley).

As a more than 20-year veteran of the oil and gas industry and current president, pipelines of TransCanada, Russ Girling holds a front-row seat on such issues, overseeing a 41,000-km pipeline network that transports the majority of Western Canada’s natural gas production to Canadian and US markets. Previous experience as TransCanada’s executive vice-president, corporate development, and chief financial officer speak to his knowledge of industry finances, risk management, and project evaluation, among other areas for which he has had overall responsibility at TransCanada.

Keystone

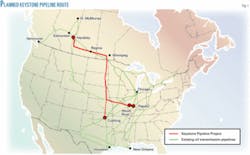

Known primarily as a transporter of natural gas, TransCanada’s largest and highest-profile current project, the Keystone Oil Pipeline, will carry 435,000 b/d of oil-sands crude 1,830 miles from Alberta to the US Midwest (Fig. 1).

With an in-service target of late 2008-early 2009, the project is currently going through regulatory approval, part of which addresses a request by TransCanada to transfer 530 miles of Canadian line from gas to oil service. With 1,070 miles of the line to be built in the US, the 530-mile converted stretch represents the bulk of the Canadian portion, making approval of the service transfer key to the overall project.

The National Energy Board public hearing considering TransCanada’s Section 74 application to transfer a portion of its Canadian Mainline natural gas transmission facilities to the Keystone Oil Pipeline Project for the purposes of transporting crude oil took place Oct. 23., with Girling expecting a decision by late first-quarter 2007.

TransCanada’s Section 52 full-facilities application for Keystone has yet to be heard, but the Section 74 application is the key, he says. “Once we know that, the rest of the facilities application will be more akin to what we’ve done in the past, and we’re really comfortable with that process, so we’d become a lot more comfortable with the spending of capital” to meet the in-service target, he says. Even without full approval of Section 52, “we’ll start spending money in larger amounts post the Section 74 decision.”

Little debate surrounds the need for the additional crude capacity. Instead, concerns regarding TransCanada’s transfer request center on its potential effects on the existing gas infrastructure. According to Girling, such concerns are unwarranted; the capacity that would be transferred represents a long-term excess in the Canadian system.

Forecasts in the 1990s which showed continued growth in Canadian natural gas supply prompted approval of the 1.5-bcfd Alliance Pipeline. When Alliance came on in late 2000, Girling says it removed 1.5 bcfd from TransCanada’s system. This capacity has yet to be replaced, even while in-Alberta consumption has grown, and TransCanada now has between 1.5 and 2 bcfd of spare capacity that the company forecasts will not be called on again.

But others wonder what will happen if coalseam gas is larger than currently forecast, or traditional supplies increase faster than is currently forecast. They also wonder what will happen when Mackenzie and Alaskan gas is brought online.

Girling says TransCanada has run several scenarios including each of these variables as well as the possibility that Fort McMurray oil sands operations will become less gas-intensive as technology advances, and all have concluded that the capacity will not be needed for gas transport.

Even TransCanada scenarios involving mid-winter peak days indicate that the capacity will not be needed for gas service again. Others disagree, insisting that the capacity will be needed for short increments in the middle of winter. The industry is divided, with CNRL, Conoco, and Suncor agreeing with TransCanada’s figures, while EnCana and Devon foresee the possibility that the capacity will be needed at some point.

Opponents have also raised concerns regarding the fuel-based costs of the increased compression that would be required to move the same quantity of gas through a smaller system. Girling says TransCanada forecasts a negative net present value to gas shippers of about $100 million over a 10 to 15-year period for incremental fuel costs.

This would be balanced, however, by removal of rate-based costs associated with the line of roughly $110 million. These forecasts are based on underlying TransCanada forecasts of gas prices and throughput, with those who disagree with these figures using different underlying price and throughput bases.

Girling believes the NEB will end up adjudicating the issue in the end. He also believes, however, that the transfer proposal serves the greater public interest.

Even those who oppose the change would admit that “at best we’re going to need this capacity a few days a year. Our view is that the greater public interest is served by using it every day as a crude oil pipeline, especially with the constraint we see in terms of crude oil capacity requirements in the 2008-09 timeframe, when the industry could face apportionment,” Girling says.

“If you take a look at the detrimental impact of not having this pipeline in place at that particular point in time, compared to any kind of scenario you can run on costs on the gas side, the benefit far outweighs the cost,” Girling says. The National Energy Board’s mandate is to look at the broader public interest; TransCanada’s argues that interest is better served by using this pipeline as a crude oil pipeline. “The benefits are substantial.”

TransCanada is also considering extending the Keystone project to Cushing and has been gauging consumer interest both in Cushing and on the US Gulf Coast before holding an open season. Potential customers have responded favorably, but only the open season will show if there is commercial interest in the system beyond the current Patoka-Wood River, Ill. terminus.

Not alone

Given the continued upswing in activity in Alberta’s oil sands, other companies are also eager to participate in bringing future production to market. Between these competing proposals and Arctic gas projects such as the Trans-Alaska Gas Pipeline and Mackenzie Valley Pipeline, concern has emerged over the availability of material and human resources needed complete them all.

Girling expects that market forces will act effectively to stage the projects, rather than allowing each to proceed independently. He sees the first stage of Enbridge Energy’s Southern Access program and Keystone as the first two projects to advance, both having secured commercial underpinning and now able to begin securing pipe and labor.

“The further you move away from Fort McMurray and Alberta, the easier [finding labor] gets,” Girling says. “You’re still competing for steel and we need to make certain decisions around steel. But what we have is a commercial underpinning that says our project should go, assuming we get regulatory approval.”

Girling expects that similar market forces will guide the direction of resources to other projects further down the road but is hesitant to speculate regarding the sorts of constraints that might be encountered by future projects or the viability of any particular pipeline plan. He describes the securing of long-term commitments from shippers, which TransCanada secured for Keystone in early 2006, as the most difficult part of any large pipeline project and the key to each of them.

Beyond these two projects, there is “going to be need; no question,” Girling says. “If the NEB curves are correct, and we would concur generally with those, we’ll need another pipeline or expansion, probably a couple years out from ours. What is less clear, according to Girling is the route - south, west, or a different direction altogether - that the next pipeline will follow, and how much of the capital involved in building it will actually get spent in Ft. McMurray.

“The market isn’t making those commitments,” Girling continues. “The market has committed to the first part of Southern Access and to our pipeline.” The next expansion associated with Round 1 would be associated with the Cushing or Gulf Coast extensions, and “right now we’re still testing whether people are willing to underpin that or not. They’re all still working on their internal plans on how they’re going to spend their capital and whether they need that crude to show up and when they need it to show up.”

TAGP

As the state of Alaska continues negotiations with ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, and BP to establish the terms dictating the southward movement of North Slope natural gas, TransCanada remains on the sidelines as a very interested observer. “We’ve stepped away from our rights [in Alaska] and said whoever’s going to build this project, we’ll grant our rights to them in order to expedite the project,” Girling says.

“We just want to make sure, once we hit the Canadian border, that our historic rights are recognized in whatever negotiated arrangement we come up with to move that gas further downstream.”

The historic rights to which Girling refers are part of 1985’s Northern Pipeline Act, which TransCanada sees as giving it rights-of-first-refusal regarding any plans to move Alaskan natural gas through Canada.

“I think one need only look at the Mackenzie Valley to see the impact of the regulatory process if it’s not defined as well as it is under the Northern Pipeline Act,” Girling says. “It’s mired in the joint-review panel process,” which incorporates thousands of agencies that have to “opine, grant permits, and approve the project.

“There already was a hearing before the NEB, 30 years ago, and they granted the certificates to TransCanada to build this pipeline,” Girling continues. “We’ve been saying that for a number of years, and people say that there could be an alternate way of doing this.”

“And maybe there could be, but our view is that you’d have to change the law to do it. But even if you were to change the law, our question would be why you would do that and put yourself just in the position that Mackenzie’s in right now.”

In addition to its regulatory footing, Girling cites TransCanada’s experience in both building and operating Arctic and near-Arctic transportation systems as factors which give it an advantage in the TAGP project, pointing in particular to TransCanada’s rights-of-way from the Alaskan border through the Yukon and its already-established Alberta system.

“Once you bring the gas from Alaska to Alberta, rather than having to build from Alberta to a market, dropping all that gas off in one market and spending that capital, you can integrate with TransCanada’s system and the ultimate outcome will be something that’s far less expensive than [building] downstream,” Girling says.

Looking forward

Looking beyond the current projects at the health of the energy industry in general, Girling remains skeptical of those who project a linear pattern of demand growth based on the current rapid expansions of economies such as China’s and India’s, noting that any sort of economic disruption will lead rapidly to a reduction in demand and with it, price.

“Production comes on in chunks, usually,” Girling says, remarking that price will continue to impact field development in both gas and oil and that a low gas price in North America for an extended period will impact producers’ willingness to commit capital to moving Arctic gas to market.

Girling sees similar forces at work regarding new facilities in the oil sands. “I’ve been in this business for more than 20 years,” he says, “and I’ve seen the predictions of $100 oil and I’ve seen oil at $10. I don’t think we’re going back to $10. But price volatility still exists [and affects production] decisions for both conventional and nonconventional supplies.”

Career highlights

Russ Girling is president, pipelines, of TransCanada Corp., where he has overall responsibility for the company’s regulated businesses, including natural gas and oil pipelines in Canada, the US, and Mexico.

Employment

Prior to his current post, Girling was executive vice-president, corporate development and chief financial officer of TransCanada. He had overall responsibility for finance, accounting, treasury, taxation, risk management, corporate strategy, corporate development, investor relations, and project evaluation. Girling was responsible for TransCanada’s $4 billion debt reduction and balance sheet restructuring during 2000.

Through 2001, he was also president of TransCanada Gas Services and was responsible for its ultimate disposition. He earlier served as executive vice-president, power, where he had overall responsibility for the creation and management of subsidiary TransCanada Power. Prior to joining TransCanada in 1994, Girling held marketing and management positions at Suncor Inc., Northridge Petroleum Marketing, and Dome Petroleum.

Education

Girling holds a bachelor of commerce degree and an MBA in finance from the University of Calgary.

Affiliations

He is a director of several companies, including Agrium Inc. and Bruce Power Inc. Girling is also director of the Alberta Children’s Hospital Fund.