Pipeline engagement eases move to ULSD

Active participation by the US pipeline industry in the transition to the use of ultralow-sulfur diesel (ULSD) has helped the change occur smoothly. The pipeline industry participated in the development of regulations governing ULSD, establishing a designate-and-track procedure to ensure sulfur-content requirements of 15 ppm are met when the material is sold following transportation.

Designate-and-track is a system designed to designate the classifications of distillate flowing through the US pipeline system and track the progress of various batches thus designated.

Background

The initial question regarding the pipeline transition to ULSD could best be characterized as “can the product get from here to there without being degraded.”

A 2001 US Energy Information Administration report on the process surrounding the transition pointed out three key uncertanties1:

- Protecting the product integrity of 15-ppm product would be more difficult than protecting the product integrity of 500-ppm highway diesel. Not only is the sulfur specification lower, with less room for error, but the relative potency of the sulfur in products further upstream is also potentially higher.

- The behavior of sulfur molecules in ULSD had not been field-tested to allow conclusions about whether pipeline wall contamination is a real problem or simply a fear, and whether the migration of sulfur will require a significant increase in the volume downgraded at interface.

- The accuracy and availability of test equipment were unproven.

Response

As of Oct. 15, 2006, regulations required retailers selling ULSD to adhere to the refinery-gate standard of 15 ppm.

In order to do so effectively, the pipeline industry’s designate-and-track program had to consider a wide variety of variables, including:

- Product mix transported and its sulfur contents.

- Length of the pipeline, as well as the number of handoffs between pipelines or traverses through breakout tanks.

- Size of the pipeline.

- Flow rate.

- Fungible vs. segregated or batch system.

ULSD initially left the designate-and-track process upon leaving the truck terminal. Subsequent revision, however, has allowed for registration of mobile facilities as well.

Designate-and-track requires each facility in the ULSD chain-refiners and blenders, pipelines, terminals, trucks, rail cars, and marine transports-to file reports indicating total distillate volumes, by designation category, delivered or received in a given quarter and year.

Compliance objectives include:

- Generating accurate and complete designations, records, and reports.

- Meeting the applicable sulfur standard.

- Maintaining designation balances and anti-downgrading limits.

The US Environmental Protection Agency will produce computerized reviews of reports, as well as performing audits and inspections.

Each party in the ULSD chain sets and manages its own sulfur-receipt specs. Reports and records must show that handoffs of material match for each compliance period and transaction. Terminal handoffs must match the pipeline specs, but the terminal can change material designations as long as it meets compliance period balances. Terminal-to-trucker handoffs must show “substantial agreement” and include an explanation if this level of agreement is not met.

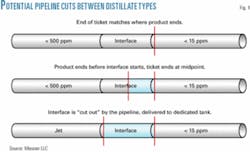

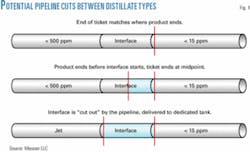

Figs. 1 and 2 show potential approaches to executing cuts between distillate types and between gasoline and distillate, respectively.

Reports and records must also show that material balances were maintained for the compliance period. Designate-and-track allows a 2 vol % tolerance for pipelines to account for volume swell, metering, and other measurement variables.

Designate-and-track also allows downgrading of up to 20% of material.

Off-spec material

Delivery of off-spec material will likely result in a shutdown of receipt or delivery to prevent additional off-spec material being shipped. This would trigger additional sampling and testing to verify the original results.

If additional tests confirm the material as off-spec, testing by an outside laboratory may occur to further verify the results. At this point, the shipper and the pipeline would likely collaborate to determine what options might be available.

The party in possession of off-spec ULSD at the time of testing is presumed to be liable for violations of the sulfur standard. The party in possession is responsible for accurately representing how the product can be legally used.

In general, if a pipeline samples and tests the product upon receipt and finds it to be compliant ULSD but later finds that it is no longer on-spec, the pipeline would be required to regrade the product to LSD or off-road and would be liable for the regrade cost.

The pipeline becomes liable in a legal sense, and susceptible to EPA fines, if it fails to recognize the off-spec situation and continues to represent the fuel as being ULSD compliant when it is not.

In the event that the party in possession wants to contest its liability, possible defenses include producing documentation that accounts for the product and shows that it didn’t cause the material to go off-spec.

If the parties involved in handling the product cannot agree as to where it went off-spec and go to the EPA to settle the dispute, the EPA will examine the adequacy of the parties’ quality-assurance and quality-control programs as part of making its decision.

If an EPA test shows violation, while the terminal test of the same fuel shows compliance, the terminal may also be able establish a periodic sampling and testing program as part of its defense.

The EPA will allow 3-ppm variability in sulfur testing between labs for the first 2 years of the ULSD program, after which 2 ppm of variability will be allowed.

Redesignation or downgrading of material as a result of contamination by interface with a higher-sulfur product is allowed, subject to the 20% limit of the designate-and-track program. The shipper, working with the supplier-refiner, determines what redesignation to give an off-spec material.

Parties are only to report volumes downgraded while in custody of their facilities. The receiving facility determines redesignation in the event that the product is upgraded. Product can also be blended back to specification or regraded to another product grade.

Clean Air Act guidelines allow for a maximum civil penalty of $32,500/day/violation. In an effort to remove any economic benefit of non-compliance, however, designate-and-track presumes that the material was in the distribution system for 25 days, raising the potential per violation fine to $800,000.

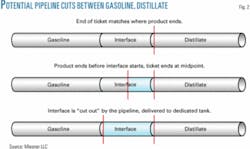

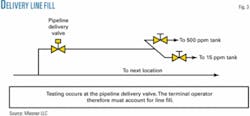

Custody-transfer points offer the highest likelihood of challenges under designate-and-track. Fig. 3 shows a simplified example of delivery line fill. Testing at the pipeline’s delivery valve requires that the terminal operator understand and be able to account for line fill.

Supplying facilities are required to submit a Certificate of Analysis (CoA) identifying the product as meeting the requirements of the pipeline. Pipelines conduct product sampling and testing as an oversight to ensure the CoA is representative. Sampling and testing occur upon receipt, in transit, and upon delivery.

Carriers’ sulfur cut-off spec for receiving material from the refiner-blender varies but is typically 8 ppm. Pipelines that do not transport other high-sulfur products, for example gasoline and ULSD only, can afford to set a more liberal specification. Pipelines that transport products that can add sulfur need to be more conservative. Small-refiner gasoline could also be a source of sulfur.

Short pipelines will typically experience a lower level of sulfur pickup from interfaces. Long-haul pipelines will typically experience a greater loss of ULSD due to more numerous sulfur interfaces.

Large-diameter pipelines will generate more sulfur interface due to the greater surface area where the products meet.

It is common for products to move on several pipeline systems between the refinery and the final destination. This is most common with Petroleum Administration for Defense District (PADD) III production moving to PADDs I and II. Each handoff between pipelines risks addition of sulfur from valve timing and line flushes between locations. Staging products in breakout tanks within a pipeline system can also add sulfur.

Fungible pipelines run on product cycles where receipt volumes are commingled and stripped off at delivery terminals en route. Commingling like products requires strict oversight and testing to protect the fungible pool from contamination.

Segregated systems receive specific batches and usually deliver them back to the supplier at a new location. The batches are not commingled and will move intact, with the specification properties unchanged. There is, however, still a chance that sulfur can be increased, depending on how products are sequenced, valve timing, and flushes between facilities.

Some carriers are very explicit in circumstances where material might be above their cut-off spec but still below 15 ppm, having zero tolerance for variation. Others are somewhat more flexible and willing to provide a waiver depending on the degree to which the product is off-spec, destination options, and other variables.

Colonial Pipeline Co. and Olympic Pipe Line Co. each have specified a maximum of 8 ppm for ULSD entering their systems. Explorer Pipeline Co. allows 8 ppm for ULSD received directly from refineries into its system but drops the limit to 7 ppm for ULSD originating in Lake Charles, La., and Port Neches, Tex.

Buckeye Pipe Line Co. will take ULSD up to 8 ppm from refineries and up to 10 ppm from connecting carriers. At Marathon Pipe Line LLC, the acceptable sulfur content depends on the source and delivery point (OGJ, May 22, 2006, p. 18).

The transition

Concerns surrounding the transportation of ULSD through pipelines have included:

- Protecting the integrity of a 15-ppm product.

- Potential migration of sulfur molecules in a 15-ppm environment requiring a significant increase in the volume downgraded at interface.

- Reliability and accuracy of test equipment.

- Potential price spikes or lack of spot availabilities during the transition period.

Tests late in 2005 by the Association of Oil Pipe Lines and the American Petroleum Institute indicated ULSD can pick up as much as 3 ppm of sulfur contamination between the certification tank and pipeline entry, while tank farms and handoffs “continue to contribute 1-2 ppm each.”

That study concluded potential contamination points would be identified and managed as pipeline companies gain experience in handling ULSD. But it also said dedicated ULSD infrastructure “should be considered,” since “off-spec” distillate could “lock up” the distribution system, affecting gasoline and diesel supply. AOPL said its members are spending an estimated $500 million to minimize contamination (OGJ, May 22, 2006, p. 18).

Jim Scandola, Buckeye’s senior manager, transportation, sees the introduction of ULSD as having proceeded smoothly to this point. “The product is being tested and certified by the supplying refineries prior to shipment. There have not been any surprises from my perspective,” he told OGJ.

Regarding provisions of designate-and-track that hold the party in possession of off-spec ULSD responsible for its disposition, Scandola said that this is not a problem “as we already hold ourselves accountable for any product contamination or regrade situation for all products in our custody. Our oversight program will be robust enough to recognize these situations and keep the risk of inaccurately representing ULSD as on-spec very low.”

Scandola said Buckeye is similarly prepared to handle the 20% limit on product downgrading. “Our experience thus far is that [the restriction] is rather generous. If a facility continues to downgrade up to 20% of their annual volume, they shouldn’t be in business. At least they will make other carriers the carrier of choice in a competitive environment.”

Colonial also reports a positive transition to this point. The company budgeted $60 million to overall ULSD improvements, including more than 300 valves and 4 new tanks (2 in Atlanta, and 2 in Greensboro, NC). The new valves are positive-sealing valves, which minimize any contamination of ULSD by other products (Fig. 4).

Colonial Vice-President Jerry Martin explained that “the extra storage space, combined with changes in how we sequence products in the pipeline, were key improvements. ULSD is bracketed with low-sulfur diesel to further protect ULSD shipments.”

Colonial’s Phase One improvements committed the company to on-spec shipments as far north and east as Fairfax, Va., according to Martin. “We were able to complete equipment upgrades at Mitchell Junction in rural, central Virginia in time to extend shipments throughout the state, including the Tidewater area [Figs. 5-7]. Test results into Dorsey Junction (central Maryland) were also positive and allowed us to begin scheduling ULSD into that facility, which serves Maryland, including Baltimore.”

Colonial is currently studying a second phase, which could mean upgrades from Dorsey as far north as Linden, NJ. “We’re carefully studying the [Linden] test results we’re seeing so far,” said Martin, noting that market demand would also a play a role in the timing of any second round of improvements. Martin said that “we regard shipments all the way to Linden as a matter of when, not if.”

Initial indications from California, which completed a California Air Resources Board-mandated transition to ULSD for road use as of Sept. 1, 2006, show no significant supply or price disruption. The current EPA deadline for universal use of ULSD is Dec. 1, 2010.

Cost recovery

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in June began issuing orders responding to surcharge tariff filings from pipeline companies designed to recover the costs associated with the transition to ULSD.

In responding to filings from Norco Pipeline Inc., Wood River Pipeline (operated by Koch Pipeline Co. LP), and Buckeye, FERC said that each pipeline must account for all costs and revenues related to ULSD surcharges separately and must footnote amounts attributed to the surcharge invested in carrier plant on p. 212 of its annual Form No. 6 filing and any revenues and expenses attributable to the surcharge on p. 700 of its filing. FERC’s goal in requiring the Form No. 6 footnotes is to be able to back out costs associated with the ULSD surcharge when deriving appropriate rate index adjustments in 2011.

Some FERC orders have denied filings. These include denial of Magellan Pipeline Co.’s proposal to distribute ULSD-related costs over its entire system.

SFPP LP’s tariff surcharge has been protested by Tesoro Refining and Marketing Co. and others that contend that SFPP has failed to describe costs of additional facilities or services related to the ULSD transition.

Acknowledgment

The author acknowledges the contributions of the AOPL-API ULSD Fuels Team, its Designate & Track Roundtable, and the individual participants in both in writing this article.

Reference

- “The transition to ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel: Effects on prices and supply,” US Energy Information Administration, 2001.