When project developers propose building an oil or gas facility-or any type of industrial project-they face a gauntlet of stakeholders in the siting and permitting processes. Worldwide such stakeholders raise difficult and often appropriate safety concerns that project sponsors must address seriously. In certain European and other jurisdictions, such public-safety risks are regulated against finite safety criteria that focus the policy discussion on quantifiable risks and effective solutions.

In the US, however, public-safety concerns have been transformed into legal and political weapons. With various motivations, opponents of proposed developments raise safety-related objections in virtually every possible venue, frequently distorting facts in a campaign to increase public anxiety and generate fiercer opposition.

For example, Tim Riley, a trial lawyer in Oxnard Shores, Calif., who represents local opponents of various LNG projects proposed for construction in Southern California, said of LNG carriers: “It’s such a tremendous source of destruction that they don’t need a bomb.” Riley’s law firm produced an advocacy film that depicts an LNG tanker exploding with a force it calls “55 times [as great as] the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima.” Riley’s film was selected for screening at the 2005 Malibu Film Festival despite such fictional science and its dearth of policy analysis.1

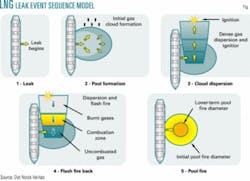

In contrast, Fig. 1 on pg. 23, illustrates hazardous effects as they typically may occur from a worst-case LNG leak, as analyzed and determined by risk management company Det Norske Veritas.

Much safety disinformation in the US is intended not to ensure that project sponsors take appropriate safety precautions but to derail the siting process entirely-and all too often such strategy succeeds. Many developers have seen their projects become the subject of alarmist public-safety propaganda, and important infrastructure developments have failed as a result. This trend is leading to severe consequences, not only for project sponsors but also for US economic and energy security as a whole.2

In an open society such as the US, transparency is vital to ensure that due process is achieved in siting and permitting major projects. Multiple venues provide many opportunities for stakeholders to raise critical issues so no community or individual is burdened with unacceptable levels of risk. As siting processes in the European Continent, UK, Scandinavia, Hong Kong, and Australia demonstrate, however, due process need not require open-ended and unlimited debate to persist even after legitimate safety concerns are resolved appropriately. These countries mandate use of widely accepted and scientifically based risk criteria (see story, p. 20). Because US siting and permitting laws generally have not defined criteria for determining acceptable levels of risk to public safety, open-ended debate has become commonplace in US development projects.

To bring greater rationality to siting and permitting processes, developers and policymakers should endeavor to change the nature of the public-safety debate in the US from the current focus on improbable worst-case scenarios to a rational assessment of cumulative safety risks. They can accomplish this by using criteria-based approaches in their development efforts today and by advocating objective and quantitative methods of analysis in ongoing policy discussions (see story, p. 19).

Such criteria-based approaches, which have proved successful in other industrialized, democratic countries, would ensure that critically important American oil and gas projects are vetted in rational public-policy processes rather than in emotionally charged propaganda wars.

NIMBY warfare

The growing epidemic of “not-in-my-backyard” (NIMBY) opposition has important ramifications for US economic and energy security. The bipartisan National Commission on Energy Policy has prioritized siting as “a major cross-cutting challenge for US energy policy.”2 Unreasonable roadblocks threaten US national interests by overstressing existing infrastructure, constraining the diversity of energy supplies, driving prices upward, and in some cases actually harming the local environment by delaying the retirement of aging facilities. The commission notes, “Many of the constraints result from processes in which local concerns trump broader regional or national objectives.”

As the list of site uses local communities deem undesirable grows to dwarf the list of acceptable uses, important projects have become ensnared in a morass of public-safety opposition. For example:

- LNG terminals. NIMBY opposition has distorted siting processes for LNG terminals in the US-most notably in the Northeast and on the West Coast. Developers have shelved a number of projects, in part because of protracted public-safety opposition.

- Refineries. Even as demand for refined petroleum products has grown steadily, no new major refinery has been built in the US since 1976, primarily because of local siting opposition. An explosion at BP America Inc.’s Texas City, Tex., refinery in March 2005 that killed 15 workers and injured 100 others exacerbated such concerns.3

- Nuclear power plants. The Three-Mile Island accident in 1979 brought nuclear-power development in the US to a standstill. Now, amid rising oil and gas prices and concerns about air emissions from fossil-fueled power plants, utilities hoping to develop a new fleet of nuclear power projects face deep-seated fears about the safety of nuclear energy.

- Hazardous material facilities. NIMBY opposition to new hazmat facilities effectively forces capacity expansion to occur at existing sites and concentrates environmental, health, and safety risks disproportionately at locations already affected by these risks.4

In each case, local opposition is fueled by popular perceptions of a given technology’s safety and security risks, rather than the actual degree of risk a proposed facility would present to the local community. In the world of politics, perception is reality. As a result, if a technology is perceived to have doomsday potential, decision-makers tend to focus siting and permitting processes on preventing or mitigating theoretical doomsday scenarios. This practice threatens US energy security because it creates unintended adverse consequences for critical-infrastructure development efforts.

First, it subjects technical and engineering considerations to emotional and political judgments rather than objective and scientific analyses. Safety and security issues are most effectively addressed by evaluating the facts and prescribing appropriate technical solutions. But when emotions and politics become primary factors in the public-safety analysis, decision-makers tend to focus on the wrong priorities. Instead of working to prevent and mitigate the most likely hazards, which generally have smaller consequences and therefore less emotional or political impact, efforts focus on worst-case scenarios that would have larger consequences but might be practically impossible. The result is that safety, security, and emergency-response measures may be less effective and more costly than they would be if they emerged from a more objective process.

Second, the practice of assessing project risks in a subjective way tends to isolate those risks from the totality of hazards facing local communities, compared to society in general. As a result, political dynamics become more important than objective facts, and some communities are forced to accept a greater cumulative level of risk than decision-makers would consider acceptable under a more rational and equitable framework.

Third, the current subjective environment for risk analysis causes decision-makers to rely on design codes and operational standards to protect them from legal and political fallout. Such codes do not provide a comprehensive safety standard because by their nature they do not contemplate the full range of possible scenarios. Incidents occur even when codes are fully met, and decision-makers can be held reasonably liable for failing to anticipate such incidents and mitigate their effects.

Fourth, because siting processes do not quantify risks in a rational way, hazard insurance policies might focus on the wrong hazards and not accurately reflect the likelihood or cost of events being covered. Industrial incidents that pose major public-safety and security risks are relatively rare, and therefore they are difficult for insurers to evaluate when developing insurance policies. As a result, policy premiums may be overpriced for some risks and underpriced for others.

Finally, a public-policy focus on barely plausible worst-case scenarios can kill some projects before they get started. No matter how astronomically unlikely it might be, if a doomsday scenario is frightening enough it will drive policy-makers to shun even the most important or well-conceived project.

When taken together, these and other unintended consequences have impaired America’s ability to understand and address the very real safety and security risks that come with living in an industrialized world.

Defining risk criteria

Most educated citizens recognize that energy is a basic need of modern society, and they accept that meeting this need carries certain safety and security risks. For example, few individuals would give up electricity just because a faulty appliance might someday electrocute them. At the same time, however, groups of people often seem to indicate the only acceptable level of risk is zero, and big corporations or government leaders should be expected to protect the population from all conceivable risks.

Risk-acceptance criteria can help to move siting and permitting processes beyond such irrational notions. Ideally, risk-acceptance criteria will be part of public policy, with society itself reaching a consensus about acceptable risk levels and government regulators enforcing those criteria. But in the absence of formal regulations, developers can invoke internationally recognized risk criteria to improve the effectiveness of their own risk-mitigation efforts, while moving the public-safety debate forward and defusing an emotionally charged debate over worst-case scenarios.

In general, criteria-based methodologies define risk as a function of statistical probability multiplied by consequence and then set limits on the levels of risk that individuals and society are obliged to accept. A common approach defines risk criteria as the number of incidents that will be considered acceptable over a given period of time. Potential incidents are evaluated in terms of their frequency and consequences, with mitigation measures required for risks that exceed accepted criteria.

The criteria themselves can be specific or abstract; various jurisdictions and industry segments take different approaches to defining risk criteria for individuals and groups (see tables).

Generally, individual risk-acceptance criteria measure the risk to a single person, who can be a representative of an actual group, such as plant personnel, or a theoretical marker, such as a person spending 100% of his or her time standing at a point inside or outside a facility. Some jurisdictions base their individual risk-acceptance criteria on the group with the population’s lowest mortality rate-which demographers in Europe have identified as 14-year-old girls. Using this benchmark, and allowing only a negligible 1% risk increase, cumulative risk-acceptance criteria have been established (in Holland for example) of one incident in every 100,000 years for existing facilities and one every 1 million years for new facilities (Table 1).5

Similarly, societal risk-acceptance criteria measure risks to a large number of people, in addition to the public’s response to a potential incident (Table 2). Societal risk usually is expressed in the form of FN curves, derived from the cumulative frequency (F) and the number of fatalities (N) from a given hazard. Again using Holland as an example, societal risk-acceptance criteria specify an FN slope curve of -2, with a maximum tolerable risk equivalent to one fatality in 1,000 years.

In each case, such criteria provide objective benchmarks that lend credibility to developers’ safety documentation and eliminate safety as a reason for opposing industrial development; once the safety criteria have been satisfied, the debate can focus on the actual motivations for opposing a project, such as its effects on air and water quality, local property values, and aesthetic or recreational factors.

Criteria problems

However, this approach can raise dilemmas for developers and policy-makers. Specifying an “acceptable” number of fatalities, for example, can seem offensive or immoral; even one fatality in 1,000 years seems unacceptable to a voter who envisions his or her own 14-year-old daughter as the theoretical victim. The criteria approach can appear to do the unthinkable: “set a price on human life.”

In addition, when risk-acceptance criteria are set loosely enough to allow the continued operation of existing facilities that were built under obsolete codes and standards, those criteria might be considered too lenient for new projects. But setting them tighter might preclude building any new facilities in some industrialized areas because hazards from grandfathered activities might already be posing cumulative risks that push the limits of established criteria.

These dilemmas are relatively manageable, however, compared to the dilemmas created by the current consequence-based approach to analyzing risks. Separate criteria for new and existing facilities, for example, can provide workable grandfathering provisions. And various ways of defining criteria can help to minimize the emotional backlash of valuing human lives.

The important principle is to ensure that the cumulative risks of hazardous activities are shared equitably in the society that reaps the benefits of those activities. To achieve this goal, criteria-based approaches to siting and permitting are more effective than consequence-based approaches. Several LNG Terminal developers in the US, for example, have documented public risk with methods that can be compared to risk acceptance criteria, if they had xisted, or to criteria used elsewhere for reference. Their approach has proven useful in public hearings and governmental assessments. Risk-based instead of consequence-based safety documentation also has been included in US federal permit applications for LNG terminals.

Beyond doomsday

In the US, industrial siting and permitting processes evaluate safety risks principally through environmental impact studies (EIS). The EIS process requires project developers and regulators to measure risks, but most statutes do not specify risk limits or criteria that projects must meet. In other words, US laws compel developers to study and disclose safety risks, but they do not explicitly regulate total risk levels. This leaves significant room for uncertainty in siting and permitting processes.

Some notable exceptions exist, however, such as the federal and state laws that set criteria for various air and water emissions. Under the Clean Air Act, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates emissions of so-called “criteria pollutants” that are measured in parts-per-million.6 And local ordinances establish criteria limits for noise, measured in decibels at a specified distance. Many such laws address specific nuisances rather than generalized safety hazards, but they illustrate how US regulatory frameworks routinely use criteria to regulate industry facilities and operations.

Further, recent US government efforts to address security threats-especially those involving terrorist attacks-are establishing new models for evaluating risks and certifying mitigation measures. Last year the US Coast Guard published and enforced Navigation and Vessel Inspection Circular (NVIC) 05-05, which established guidelines for safety and security at proposed onshore LNG regasification facilities and defined processes for assessing the suitability of waterways for LNG transit.7

By their nature, terrorism and other security threats involve human variables that are difficult to predict through scientific modeling. As a result, criteria-based methods are less useful for addressing security threats than they are for safety risks arising from unintentional causes. Nevertheless, the processes defined by NVIC 05-05 exemplify the type of objective risk-assessment protocols that will help stakeholders manage security risks involving industrial projects.

In fact, such objective protocols are at least as important for safety risks as they are for security concerns. In recent years, industrial accidents have caused numerous fatalities in the US but none from intentional acts on energy infrastructure. The recent fatal incidents at the Texas City refinery and at the Bellingham gasoline pipeline in Washington State demonstrate the importance of adequate safety risk protocols (OGJ online, Dec. 13, 2002). As part of the siting and permitting process, a quantitative, criteria-based methodology for analyzing safety risks will help decision-makers to see through the fog of a propaganda war. At the same time, objective safety criteria will help to focus the public debate over critical project siting, ensuring that safety-related decisions are based on a rational analysis of the risks rather than an unhealthy fixation on doomsday fears.

References

- Authoritative research, commissioned by such agencies as the US Department of Energy quantifies the worst potential consequences of even a massive LNG leak at a tiny fraction of the Hiroshima event. Example: “Guidance on risk analysis and safety implications of a large LNG spill over water,” Sandia National Laboratories, SAND2004-6258, Dec. 2004.

- “Siting critical energy infrastructure: An overview of needs and challenges,” National Commission on Energy Policy, June 2006.

- “Texas City refinery update: The price of safety complacency,” Department of Energy, Office of Environmental Health & Safety, January 2006.

- “Social aspects of siting RCRA hazardous waste facilities,” US Environmental Protection Agency, April 2000.

- “Risk Acceptance Criteria for Land-use Planning in the Vicinity of Major Industrial Hazards,” Health & Safety Executive (HSE), HMSO, 1989.

- National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS), US EPA, http://www.epa.gov/ttn/naaqs/

- “Coast Guard redefines LNG permitting,” LNG Observer, PennWell Publishing, January 2006

The authors

Ernst Meyer ([email protected]) has served as head of Det Norske Veritas LNG Department in Houston since 2003, delivering risk management services to North American LNG import terminals. He has been appointed LNG director at Det Norske Veritas effective this month. Meyer also is a principal of LNG Solutions Group-a joint venture of Det Norske Veritas, law firm Sutherland Asbill & Brennan LLP, and Ziff Energy-which was formed to provide integrated services to LNG stakeholders.

Stephen Shaw ([email protected]) is regional director for Det Norske Veritas in North America. He has worked for DNV for 20 years and also is a principal of LNG Solutions Group. Shaw is a recognized public risk expert who has been consulted by governments and policy-makers worldwide.

Jacob Dweck ([email protected]) is a partner with the Energy Group at Sutherland Asbill & Brennan LLP, a national law firm with an extensive energy practice. Dweck has 30 years of experience counseling clients on energy issues, including project development, regulatory and permitting, contracting, marine and shipping, commercial, and all other segments of the energy industry. Dweck currently chairs the 17-lawyer LNG Group at Sutherland and also is a principal of LNG Solutions Group.

Steven Sparling ([email protected]) is a core member of Sutherland’s LNG Group. He advises clients on all LNG issues, including siting of LNG import terminals and regasification facilities, project development, safety and security, stakeholder engagements, terminals capacity agreements, multiuser terminal matters, and negotiations for terminal expansion. Sparling also is a principal of LNG Solutions Group.