COMMENT: Oil production limits mean opportunities, conservation

In the face of looming oil production shortfalls, all individuals as well as nations as a whole will have to use less oil. And now is the time to begin developing programs accommodating the need for less oil. The coming shortage could provide excellent opportunities for those able to identify them and act strategically.

Civilization is increasingly dependent on oil, now the most important global commodity. The oil and gas industry has surpassed agriculture as the biggest industry in the world. At $70/bbl, the value of the world’s crude oil business is about $2 trillion/year. But crude oil is far from uniformly distributed around the world, and only a limited number of countries are significant producers.

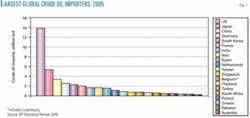

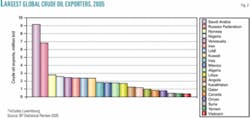

Oil production and consumption figures are published annually in the BP Statistical Review of World Energy,1 and from these figures we can determine which countries are net importers and which are net exporters.

In 2005 the export trade was 48 million b/d, and 29% of global crude oil exports went to the US, up from 27% in 2004. Japan was number two importer with 11%, up from 10% the previous year, and China was number three with 7%, up from 6% in 2004. Importing nations must find countries that are prepared to export oil to them. Normally the flow of oil into one country will come from several different sources. Adding all the exports, we find that Saudi Arabia is the number one exporter with a volume of just over 9 million b/d, up slightly from 2004. Russia is number two with 6.8 million b/d, slightly up from 6.7 million b/d in 2004, and Norway is number three with 2.8 million b/d, down slightly from 3 million b/d in 2004.

During the last 30 years, the annual increase in average gross domestic product (GDP) globally has been 3%/year compared with an average increase in oil consumption of 1.6%/year.2 In developing countries, the correlation between GDP and oil consumption is stronger than average. For example, China’s increase in GDP on average has been 8.2% during the last 5 years, and the increase in oil consumption, 8.5%.3

In its 2004 World Energy Outlook, the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecast that the increase in oil consumption would be 1.6%/year for the next 25 years, requiring oil production of 123 million b/d in 2030. A detailed analysis, however, found that this objective for the oil industry was not possible to fulfill.4

In IEA’s 2005 World Energy Outlook, the target had dropped to a 1.4%/year increase in the production of oil, and the number for 2030 was projected at 115 million b/d. The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecasts a production of 117 million b/d for the same year. Compared with today’s production of 85 million b/d, an increase of 30 million b/d in global production will be needed if IEA forecasts are correct.

According to EIA, US consumption will increase by 7 million b/d (33%) by 2030. At the same time, consumption in China will increase by the same amount but in percentage terms, by over 100%. In discussions of the global economy, only the increase in China’s demand is mentioned as a threat. China has 21% of the global population today and is consuming 8.5% of the world’s oil, up from 8% last year. In 2030 China hopes to use 12%, and there is no doubt that it can afford to pay for this increase. The US has just 5% of the global population but intends to maintain its current share of 25% of the global consumption. Compared with China, it appears that the US will have to increase its debt to pay for the crude.

If the decline in existing production and all additional demand forecasts are added, imports by 2030 will have to increase by some 30 million b/d. Would exporting countries be able to meet the demand from the net importers?

Possible production

According to Saudi Aramco, Saudi Arabia has reserves enabling a sustainable production of 10.8 million b/d for more than 50 years, but it plans to boost its production to 12.5 million b/d in 2009. This production is not sustainable, because the country would have to find new oil fields and put them in production before 2030 to maintain the same level of production. When determining possible future exports, the growing Saudi population must be taken into account, as the country will require more of its oil domestically. Exports can be expected to increase by only about 2 million b/d.

Officially, Saudi Arabia claims to have found 720 billion bbl of original oil in place. So far it has produced 15% of that, and, with a claim of 260 billion bbl as proved reserves-36% of the OOIP-the recovery factor would be 51%.

At a hearing at the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences in spring 2005, Tor Ragnar Merling from Statoil ASA presented a detailed study of recovery factors of thousands of oil fields in sizes varying from small ones to giants. The average recovery factor was 29%. Merling thought it was possible to increase this number to 38%.

Even though Saudi Arabia produces most of its crude from only a few oil fields, there are hundreds of oil fields there. If the global average recovery factor is applied to the 720 billion bbl of OOIP, the reserves would be 110 billion bbl, and with the Merling future recovery factor, they would be 160 billion bbl. Because Saudi Arabia refuses to be transparent with its oil field data, conservative planners in the future should use these numbers.

In early June, the Russian Ministry of Economics announced that Russia would reach a maximum production of 9.85 million b/d in 2009. By accepting this number as a plateau number for 20 years, taking into account that the GDP will increase 3%/year, and applying a 50% decoupling factor (when the oil consumption is less then the growth in GDP), Russian exports are calculated to be 5 million b/d by 2030-a decline of 1 million b/d.

Norway, the number three exporter today, says that in 2030 its maximum production will be 500,000 b/d, and the minimum, 200,000 b/d. The 2005 export of 2.8 million b/d will decline by more than 2 million b/d by 2030.

Mexico is another export country that will lose a big fraction of its export capacity if new fields are not discovered and massive additional production developed. According to “scout” information from Mexico, Cantarell production will decline by 1 million b/d in coming years.

Over the next 5 years, Angola and Nigeria will increase production by 3 million b/d, but by 2030, production there will have declined back to today’s levels.

To avoid any more clouds on the future stark horizon, just assume that other Middle East countries can keep their export volumes constant.

Export shortfall real

In summary, by 2030 it is very likely that there will be an export shortfall of more than 30 million b/d, and it is most irresponsible of IEA and EIA to say “Be happy, don’t worry.”

The implications are quite clear: Overall, everyone-both nations as a whole and individuals-will have to use less oil in the future. And now is the time to develop conservation tactics.

There are alternatives to oil, but they are most unlikely to be available in sufficient quantities to replace the current enormous demand for cheap oil. However, this will not necessarily put an end to society as some believe. Rather, the situation presents enormous business opportunities for individuals in the future.

The US and some other importing countries have already faced an artificial “Peak Oil” scenario in the 1970s when the taps were intentionally closed in the Middle East. When those who lived through that time think back, they will recall that life was still OK. It might be more difficult now, as we cannot foresee an increase in the production of crude oil, but by then electric cars will have replaced urban transportation.

We do have a future; life will just be quite different than it is today.

References

- BP Statistical Review of World Energy (www.bp.com).

- International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2004.

- Pang, Xionggi, IV International Workshop on Oil and Gas Depletion, May 19-20, 2005, Lisbon, Portugal, (http://www.cge.uevora.pt/aspo2005/abscom/ASPO2005_Pang_paper.pdf).

- Aleklett, Kjell, “International Energy Agency Accepts Peak Oil,” 2004, (http://www.peakoil.net/uhdsg/weo2004/TheUppsalaCode.html).

The author

Kjell Aleklett ([email protected]) is professor of physics on the physics faculty at Uppsala University in Sweden. At the university’s Ångström laboratory, he also heads the peak oil research group, Uppsala Hydrocarbon Depletion Study Group and is president of the Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas (www.peakoil.net).

This article is based on the author’s presentation entitled, “Time for an oil change: Facing the truth about the looming oil shortages,” delivered in Hong Kong June 13 during the 2nd Annual Commodity Investment World Asia 2006 conference.