National oil companies invest beyond borders

International oil companies face changing business dynamics and rising competition as national oil companies aggressively acquire reserves and other assets around the world.

Asian state-owned companies, particularly from China and India, are at the forefront. The Chinese government has pressured oil companies to intensify international mergers and acquisitions (M&A) to satisfy concerns about long-term oil supply.

Some Westerners suggest that Asian NOCs disregard financial returns in order to acquire oil reserves and production at any price. But Wood Mackenzie Ltd. analyst Derek Butter disagrees.

“It’s not just the Asian NOCs that are driving the high prices in the merger and acquisition market. It’s a lot of cash chasing a few attractive opportunities,” Butter said. “The crying of foul by the Western media probably is overdone. The portrayal of the rise of the Chinese as some sort of new yellow peril is overdone as well.”

His analysis shows Asian NOCs expanded their developing upstream businesses at reasonable cost (Fig. 1).

The growing numbers of NOCs active in the world M&A arena means both increased opportunities and increased competition for IOCs and the NOCs that are already established multinational investors, said Butter.

“I don’t see it as a battle so much as just new kids on the block turning up,” he said, comparing recent international efforts of Chinese oil companies with the growth of Western oil companies during the early 1900s.

Consultant Daniel Johnston, founder of Daniel Johnston & Co. Inc., Hancock, NH, said the prices being paid and the projects undertaken by China National Offshore Oil Corp. Ltd. (CNOOC) are best understood in a broad context. He emphasizes that NOCs and IOCs function in different capacities.

“Most of the NOCs, on behalf of their governments, are fulfilling an important role in the exercise of their nation’s foreign policy,” Johnston said. “This added dimension makes the dynamics of competition quite complex.”

Consultant Accenture issued a report on NOCs noting that state-owned oil companies differ in their priorities and structure. Analysts said an IOC needs company-specific knowledge to develop tailored strategies for doing business with any NOC (OGJ, Feb. 13, 2006, p. 28).

IOCs and NOCs interact on two fronts, Accenture said. The first is the international market, where NOCs represent potential partners or competitors to IOCs. The second is country-specific markets, where NOCs represent the state.

NOCs distinct

Relationships between NOCs and their governments involve wide-ranging degrees of state ownership and privatization, operational frameworks, sales terms with governments, trade restrictions, and fiscal regimes.

“IOCs will have to master a basket of at times unfamiliar skills,” Accenture said. “While broad-brush characterizations of NOCs may be tempting, the huge variation in NOCs’ commercial and political roles, decision-making processes, and aspirations means that IOCs cannot short-cut...relationship-building.”

An IOC’s strategy also needs to reflect a strong sense of self-awareness because IOCs must differentiate themselves from one another when seeking a partnership with an NOC, Accenture said.

ExxonMobil Corp. Senior Vice-Pres. Stuart McGill pointed out that an oil company traditionally competes with particular companies in one market while forming partnerships with those same companies in another market.

“NOCs are competitors, but they’re also coventurers,” McGill told reporters at the Cambridge Energy Research Associates conference in Houston during February. “We look continually to where we can bring something to a project that’s truly unique.”

Julian Lee, senior energy analyst for the Center for Global Energy Studies in London, also emphasized that each IOC must create its own competitive niche.

“IOCs need to be very clear about their unique selling point and convince host countries that they can offer something that the NOCs can’t,” Lee told OGJ. “This will not be easy to do, especially as much of the technology for E&P can be bought from international service companies.”

ExxonMobil’s McGill said majors examine potential relationships in the context of commercial objectives, particularly looking to share risk. Accenture analysts’ interviews with NOC executives confirmed this.

One NOC executive told Accenture, “We mainly look to IOCs to share the risk of big projects with us. We also look for their technical experience around gas.” Accenture declined to name the speaker or company, citing a confidentiality agreement.

IOC-NOC deals

The Accenture report examined how IOCs balance the challenges of developing business in an NOC’s host country while also competing internationally with that same company.

NOCs are growing increasingly sophisticated in their ambitions to broaden their holdings across the oil and gas value chain. John S. Herold Inc. research showed that M&A activities by NOCs reached a record $33 billion last year.

“The internationalization suggests that IOCs now will come face to face with NOCs more often, not only as customers, partners, or custodians in developing a host country’s resources, but as commercial competitors on the world stage,” the Accenture report said.

Models of cooperation between NOCs and IOCs are evolving, Accenture analysts said, adding that NOCs seek the technology, expertise, and capabilities that the IOCs offer in LNG, gas-to-liquids, secondary recovery, unconventional oil, and ultradeep water.

In addition, IOCs have trading divisions and infrastructure that NOCs desire. Partnerships with IOCs can help NOCs gain access to projects or transactions that an NOC might not be able to access alone-particularly on complex projects.

“The presence of a large IOC can send a signal to the international community that a country or market is really opening up, which is vital when emerging from a period of isolation,” Accenture analysts said. An example is Libya, where BG Group, Chevron Corp., and Occidental Petroleum Corp. won licenses in a recent bidding round (OGJ, Jan. 23, 2006, p. 31).

Lee of CGES expects NOCs to gain experience at managing and operating projects. They thus might become less apt to form consortiums with IOCs.

“The IOCs’ experience may be an advantage for a while, but the gap is closing,” he said.

Accenture urged IOCs to become familiar with any key NOC’s relationship with its host government, adding that successful IOCs become involved in a country well ahead of any actual deal in order to learn about the people, culture, and processes.

IOC business developers should try to capitalize on integrated project possibilities, Accenture said. A company that blends E&P, gas and power, downstream, and chemicals businesses can build appealing packages.

Accenture also urged IOCs to work toward helping a key NOC’s host country with its long-term social and economic needs.

“The IOCs that have moved beyond a philanthropic model to one that contains elements that meet the long-term strategic goals of NOCs and the nations that they serve (e.g., economic and infrastructure development, internationalization, environment, etc.) are those that have been more successful in winning business and securing a license to operate,” the Accenture report said.

For example, BP Trinidad & Tobago committed to Trinidad’s development by investing in education and community projects promoting long-term skills development for the local work force.

Asian NOCs

WoodMac’s Butter sees Asian companies as remaining very active in the international upstream M&A market in coming years.

“In the future, as the Asian NOCs become more experienced in the M&A market and begin to punch their relative weight, a new axis is likely to appear, with the establishment of big Eastern oil as major international players on a scale to rival big Western oil,” Butter said.

Butter lists Asia’s most expansive NOCs as China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC), CNOOC, India’s Oil & Natural Gas Corp. (ONGC), Malaysia’s Petronas, and China Petrochemical Corp. (Sinopec). Their completed upstream asset and corporate acquisitions totaled $13 billion during 2001-05.

Butter called that amount “relatively modest,” noting that M&A activity of similar IOCs was much higher. He compiled statistics from a five-company IOC group: BP PLC, ConocoPhillips, ENI SPA, Occidental, and Devon Energy Corp. During 2001-05, the IOC group completed acquisitions worth more than $33 billion.

“By accepting higher degrees of political risk, the Asian NOCs have generally avoided direct competition with established international players and gained access to some attractive upstream asset portfolios,” Butter said.

In addition, Asian NOCs can tolerate political risk because their core domestic operations are unlikely to face political disruption, expropriation, or major hikes in fiscal take, he said.

“Furthermore, with state governments remaining majority owners, the companies are better placed than international oil companies to mitigate overseas political risks through direct political influence and relationship-building,” Butter said.

Asian NOCs increasingly are cooperating with one another for upstream opportunities, Butter said. Various combinations of CNPC, Sinopec, and CNOOC have jointly bid for assets since 2001 rather than compete with one another.

CNPC and ONGC of India have a broad cooperation agreement in which they will jointly acquire international assets. The two are buying Petro-Canada’s 38% stake in a Syrian production joint venture for $676 million (Can.), subject to Syrian-government approval (OGJ, Jan. 9, 2006, p. 31).

“The long-term viability of a substantive partnership between CNPC and ONGC remains to be fully tested, although a joint bid for assets in Colombia is reported to be under consideration,” Butter said.

NOC-NOC deals

NOCs are establishing new relationships with one another in their desire to grow internationally, said Alex Oliveira, a senior executive in Accenture’s energy industry group.

He said relationships between NOCs focus on long-term strategic plans, while relationships between NOCs and IOCs now focus more on specific projects than on long-term arrangements.

“The demand-side national oil companies have changed the currency of competition, offering the supply-side national oil companies strategic partnerships that extend to economic and infrastructure development, far beyond the traditional deals offered by international oil companies,” Oliveira said. “This is a step change from the traditional joint venture.”

Butter agreed the NOCs are developing increasingly ambitious arrangements with one another, noting how Angola’s state-owned Sonangol developed a joint venture with Sincopec.

By using Sonangol’s preemption rights, Sinopec gained a 50% interest in Angola’s Block 18 deepwater development in 2004. Subsequently, Sonangol Sinopec International took 25% interest in Block 3/80 in July 2005 upon expiration of Total SA’s license. The venture successfully bid in recent deepwater licensing rounds.

“Agreements have also been signed on a long-term crude oil supply deal and plans for a joint study for a new refinery in Angola,” Butter said. “The importance of the Sonangol Sinopec JV relationship is illustrated by the fact that Angola is currently China’s single largest crude oil supplier, ahead of Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Russia.”

Oliveira said many NOCs view Statoil ASA as a potential model because Statoil trades on international financial exchanges and forms partnerships with IOCs on projects worldwide.

Statoil expects the growth of NOCs to continue, John Knight, Statoil senior vice-president of business development and acquisitions, told Deloitte & Touche’s Oil and Gas Conference in Houston on Dec. 7, 2005.

Knight said Statoil is one of four companies that he considers “international national oil companies.” He listed the others as Petrobras, Petronas, and Saudi Aramco.

He expects that number to grow by 2015, and he said the developing nations are changing their traditional willingness to play a secondary role to the super majors.

“The historic role is history,” Knight said.

Volatility

Crude oil price volatility has been the backdrop of heightened tension around NOCs, said John S. Herold analysts, who list the beneficiaries of volatility as Russia, Brazil, Angola, Nigeria, Venezuela, and Mexico.

Herold analyst Louis B. Gagliardi said NOCs, particularly in exporting countries, demand more from partners or prospective partners when oil prices are high.

“I think it becomes more imperative for some of these countries to safeguard their national champion because energy security is of paramount importance today,” Gagliardi said. “We are seeing the NOCs seeking higher rent. We saw the situation with Gazprom seeking higher rent for their gas in Western Europe. That got everyone’s attention.”

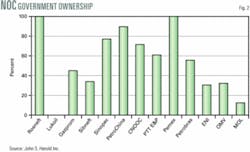

Gagliardi also noted that the government ownership stake in an NOC varies greatly from country to country (Fig. 2).

For instance, OAO Lukoil is the “national flag-bearer for Russia,” Gagliardi said, adding he expects Lukoil to continue to gather assets abroad. Although the government relinquished direct interest in Lukoil in 2004, he believes the company remains under “this NOC umbrella flavor.”

He thinks Russia wants to establish a super international competitor. “It becomes a status symbol for the Russians. Will Lukoil be aggressive? No, I think they will be more economically reasonable. They will pick and choose the assets in areas they want.”

Gagliardi expects the Russian NOCs to come to terms with the multinationals because the Russians lack the multinationals’ offshore technology and market access.

“If the Russians want to go to the far reaches of Siberia, they are going to need Western technology,” Gagliardi said.

Political stability

The host country’s political stability or instability is always a factor affecting NOC operations. While numerous presidential elections are scheduled for Latin America this year, Herold analyst Gray Peckham expects Latin American energy producers to remain fairly stable in their existing activities.

Mexico, where a July 2 presidential election required a recount and remains subject to controversy, is expected to maintain its constitutional ban on foreign investment in upstream oil and gas, he said.

Peckham said Pemex lacks the capital and the inclination to participate in the international M&A market. Instead, he expects Pemex to focus on commercializing deepwater prospects in the Gulf of Mexico.

Gagliardi said: “I don’t see Pemex actually trying to go outside Mexico. They haven’t done it yet, and I don’t think it’s where they really want to go. They have their plate pretty full.”

Pemex needs technology and capital to curb a steep production decline in mature Cantarell field, which is in 100 ft or less of water, Gagliardi said. He forecast Mexico’s production will hold flat for the next 2 years.

Peckham believes Pemex could benefit from forming partnerships with companies having deepwater experience, noting that Pemex and Petrobras have discussed cooperation.

“Hopefully, some of these talks might come into fruition, and the two might be able to find a happy medium where you take the technology that Brazil has and bring it to Mexico’s deeper waters and revive its production,” he said.

In Brazil, an October presidential election is apt to be neutral or good for the energy business, Peckham said, adding that he expects Petrobras to continue its long-term growth.

When asked about politics in Venezuela and Bolivia, Gagliardi said he believes the state oil companies there will maintain cooperation with the IOCs.

“They are going to try and extract as high a rent as possible, but they do need a market so they cannot operate in a vacuum,” Gagliardi said. “They are going to accommodate IOCs because most of the market access is, to some degree, controlled by the huge multinationals.”

Although Venezuela and Bolivia might confiscate the assets of the multinationals, Gagliardi said, government officials in those countries know it takes capital to operate the fields. They also know they need market access to sell oil and gas.

“While there is a lot of rhetoric right now, these countries realize they have to be careful about how much they bite off and that they might not be able to manage it themselves,” Gagliardi said.

Middle Eastern NOCs

Expectations for more oil price strength and the approval of several major developments in Qatar, Abu Dhabi, and Oman are encouraging for IOCs, noted a WoodMac report entitled Positive Developments for International Oil Companies in the Middle East.

WoodMac analyst Colin Lothian said the Middle East holds attractive prospects for IOCs, whom he advises to bring “patience, persistence, and pragmatism” to the negotiating table.

IOCs have access to less than 10% of Middle Eastern oil and gas reserves, he said. NOCs such as Saudi Aramco, National Iranian Oil Co., Kuwait Petroleum Corp., and Qatar Petroleum individually hold larger reserves and more valuable upstream portfolios than any IOC in the region, Lothian pointed out.

Among the IOCs, ExxonMobil holds the most valuable upstream Middle Eastern assets. Lothian estimated the company’s assets there at $18 billion, dominated by giant gas and LNG assets in Qatar and supplemented by its recently acquired 28% share of Upper Zakum oil field off Abu Dhabi.

Royal Dutch Shell PLC and Total, which rank second and third respectively in Middle East asset values, retain about the same amount of assets as they did last year, he said, noting that both have benefited from high oil prices that enhanced the value of their assets in Oman and Syria.

Occidental remained in fourth place, adding Mukhaizna heavy oil field in Oman to its developments. Occidental’s Middle Eastern assets include shares in the Dolphin gas project and Idd el Shargi fields in Qatar.

“Although several development contracts have been awarded over the past year, other long-awaited projects in Iran, Iraq, and Kuwait continue to be delayed,” Lothian said. “Political uncertainty in Iran and the continued instability in Iraq continue to hinder contract awards.”

Valerie Marcel, principal researcher at Chatham House (Royal Institute of International Affairs), wrote a book entitled Oil Titans. She interviewed Middle Eastern NOC executives, asking them about how they seek to balance their national mission with their commercial needs.

“New trends are shaping the oil and gas industry, notably an increased blurring of differences between NOCs and IOCs,” Marcel said. “Public ownership is also becoming an elastic concept.”

The range of strategic partnerships is being expanded because one model will not fit every case, she said. New contractual arrangements might be needed to define new types of relationships between producers and IOCs.

“There is no easy formula for a partnership that enables NOCs to control the development of their states’ resources while they learn the skills of the IOCs,” Marcel wrote in her book. “Terms can be found, but the will must be there too. The crucial issue for NOCs is trust, and the lack of it is a serious obstacle to developing IOC-NOC partnerships. This legacy will need to be overcome in order to meet the industry’s investment challenge over the next 10-20 years.”

For IOCs, Marcel said, cultural sensitivity and good listening are required. “IOCs should not underestimate the knowledge of NOCs,” she said. “The Middle Eastern NOCs have, after all, kept their industry running with little help from the IOCs for the past 30 years.”

She noted that a joint venture between an IOC and NOC outside either company’s home country offers “neutral territory” in which to develop a relationship. The NOC, for example, is apt to be more receptive and less intent on protecting national sovereignty than it would be at home.