Kazakhstan is endowed with significant oil and gas resources and is expected to become one of the world’s top 10 oil producers within the next decade. The high cost of doing business in the country, however, means that Kazakhstan will need to improve its institutional framework to successfully compete for foreign investment.

A large degree of risk and uncertainty continues to plague the oil and gas sector as the government makes significant changes to the petroleum tax legislation and takes an aggressive approach in “rebalancing” contractual arrangements with industry.

High levels of bureaucracy, regulatory burden, and corruption persist, and economic factors appear to be increasingly subordinated to geopolitical objectives aimed to strengthen relationships with China and Russia. The rapid pace of change and the high degree of uncertainty present significant challenges and risk to foreign investment.

In Part 1 of this three-part article, we will review Kazakhstan’s oil and gas sector and summarize production and consumption trends. Contract structures and transportation infrastructure are highlighted in Part 2. In Part 3, recent developments in the petroleum legislation and business climate will be assessed.

Introduction

Kazakhstan is a land-locked country located between Russia and China and bordering Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan (Fig. 1).

Nearly four times the size of Texas, Kazakhstan has significant oil and gas reserves and abundant mineral resources, including copper, lead, zinc, iron ore, manganese, titanium, chromium, and uranium. Proved oil and gas reserves are currently 39.6 billion bbl of oil and 105.9 tcf of natural gas, roughly 3.3% and 1.7% of the world’s total proved reserves.1

Kazakhstan ranks in the top 10 countries in oil and gas reserves. Oil reserve totals are comparable to Nigeria and Libya, and no other country in Europe or Eurasia, except Russia, has more gas reserves.

Industry and government estimates of the remaining hydrocarbon potential of the country are highly speculative, but current assessments are more realistic than the inflated and unsubstantiated claims of the 1990s.2 3 It is likely that significant oil and gas discoveries will continue to be made in the region if government policies stabilize and investor interest remain high.

Oil and gas in economy

The petroleum industry in Kazakhstan plays an important role in the health of the economy and continues to develop rapidly.

The oil sector currently accounts for nearly 30% of gross domestic product and 57% total annual export revenues (Table 1). Foreign direct investment over the past decade has amounted to nearly $30 billion, of which $20 billion is from the US.4

In 2005, investment in the exploration and production (E&P) sector reached $4.6 billion ($869 million in exploration and $3.7 billion in production), and over the next decade $4-5 billion is expected to be invested annually in the sector.1

Kazakhstan’s current share of E&P capital relative to worldwide investment levels is approximately equal to its proportion of total oil reserves, providing an indirect (and albeit, imperfect) indicator that Kazakhstan is receiving a “fair share” of international investment.

Countries make use of a broad range of tax and nontax instruments to collect revenue from the oil and gas sector. These instruments vary over time, country, and region of the world, and as one would expect, the strictest fiscal regimes tend to be in countries that offer the most attractive geological prospects, combined with political and macroeconomic stability.

Governments continually “test” the market by changing the fiscal contracts and petroleum legislation and then re-adjust the terms based on investor reaction. Kazakhstan has made significant changes to its petroleum tax legislation over the last 2 years while attempting to “rebalance” (renegotiate) previously signed agreements.

The government approach has been aggressive, leading to frequent conflicts with industry and growing investor discontent. Some industry analysts consider the legislative changes and the ascendancy of the state oil and gas company Kazmunaigaz (KMG) consistent with the global trends of oil-producing states.5 Other observers, and in particular industry participants, consider changes more detrimental and have indicated that such changes make Kazakhstan less competitive to foreign investment.2 6

Oil price risk

Mineral extraction has important macroeconomic implications on oil producing economies.

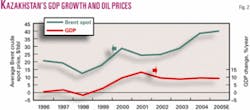

If a government obtains substantial revenue from oil production and exports, changes in oil prices will have an impact on revenues generated. GDP is a function of both the direct and indirect impact of the oil and gas sector on the economy and the ability of the state to absorb the price change (Fig. 2). Oil price risk is the contribution that changes in oil prices makes to the variance in GDP-the greater the contribution, the greater the premium.

In 2002, for example, every $1 change in the price of oil in Kazakhstan translated to about a $100 million change in budget revenue.7 Economic growth usually increases the demand for oil, but in Kazakhstan as in Russia, the expansion of the oil sector has been the primary driver for the growth in GDP.

The second type of oil price risks that governments encounter is related to the social, economic, and political impacts of changes in the prices of domestic petroleum products. Many governments try to smooth domestic oil product prices to mitigate the impacts of large changes. In Kazakhstan, the refining industry is heavily regulated through direct administrative measures and control of the transportation tariffs by KMG (pipelines) and Kazakhstan Temir Zholy (railways).

In developed economies, there are usually opportunities for local industry to provide inputs to a project or use mineral outputs for production needs. In many developing countries, however, the structural links are less extensive and the main macroeconomic impact will come from the revenue collected by the government.8

Inflow of mineral revenue will usually lead to an increase in government consumption, investment, or saving. Temporary revenue windfalls may lead to permanently higher expenditure commitments, opportunities for increased rent seeking, and corruption. A stabilization fund may help to stabilize expenditure levels over time, but worldwide experience indicates they are not a cure-all.9

National fund

The Kazakhstan National Fund (NF) was created in 2001 to help reduce the impact of volatile market prices on the economy and to smooth the distribution of oil wealth over generations.7

Its founding documents describe its mission as “stabilizing the socio-economic development of the country, accumulating savings for future generations, and reducing the country’s vulnerability to external factors.”10

The NF has both savings and stabilization objectives. The savings objectives are intended to maintain stable income across generations in anticipation of reduced oil production in the future. The stabilization objective is to stabilize the revenue from oil production, compensating bad years with the savings from good years.

The NF is an off-budget fund with all assets invested abroad in two portfolios-a savings portfolio that comprises 75% of the assets and a stabilization portfolio that comprises the remaining 25%. The funding rules have been simplified since the program was created, and as of June 2005, $5.2 billion has accumulated in the fund.

The stabilization component is triggered by a reference price for oil, set for 5 years, and currently P* = $19/bbl. If the price of oil P > P*, the excess income will flow to the NF; conversely, if P < P*, the NF will provide the difference, in terms of the loss of income, to the budget.

Production trends

Kazakhstan’s oil deposits are located primarily in the western part of the country, near and under the Caspian Sea.

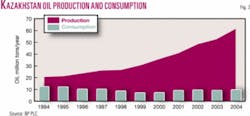

After independence, oil production declined 20% between 1992 and 1994, reaching a low of 414,000 b/d in 1995. Production reached 707,000 b/d by 2000 and 1.18 million b/d by 2004 (Fig. 3). Between 1999 and 2004, oil production grew 15%/year, nearly doubling total production, while in the first 6 months of 2005 oil production grew at a rate of 10%. Government forecasts of oil production predict levels of 3.0-3.4 million b/d by 2010.

Ownership structure

The ownership structures of Kazakhstan’s oil enterprises have changed several times since independence due to mergers and acquisition in the industry.

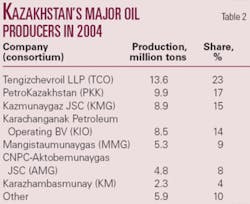

Seven enterprises currently account for more than 90% of oil production in Kazakhstan (Table 2). Led by the Tengizchevroil Consortium (TCO), the list of foreign firms includes most of the major international companies, including BP, BG, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Eni-Agip, ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch/Shell, Total; regional and national companies, such as CNPC, Lukoil, Rosneft, Romanian national oil company Petrom, Turkish National Oil Co.; and a host of smaller companies, from Canada (Alhambra Resources Ltd., Canargo, Nations Energy Co. Ltd., Nelson Resources Ltd., Nimir Petroleum, PetroKazakhstan), China (Vector Energy West), Denmark (Maersk), Hungary (MOL), the US (BMB Munai, Chapparal Resources, First International Oil Co.), the UK (Caspian Holdings, Victoria Oil and Gas), Japan (Inpex), and South Korea (KNOC, LG). Central Asian Petroleum Ltd. (Indonesia) and Ansdell Development Ltd. (offshore company) have vague or unknown ownership, which has been tied to President Nazarbaiyev, his family, or close associates.11 12

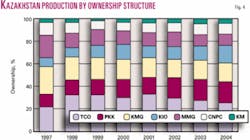

Production by ownership structure is depicted on a percentage basis (Fig. 4). In 1992, Mangistaumunaigaz (MMG) and Karazhanbasmunai (KM) were the largest producers, but these fields have declined throughout the decade. The Kumkol group of fields continues to increase, and production at Emba and Aktobe remain relatively constant.

Foreign operated ventures Tengiz and Karachaganak represent the primary source of growth in the sector. CNPC recently acquired PetroKazakhstan’s operations at Kumkol and its interest in the Shymkent refinery in a $4.2 billion buyout and is now the second largest producer in the country (Table 3).

null

Consumption trends

Demand for oil is connected to economic activity, consumption patterns, and conservation.

Throughout the decade, the demand for oil in Kazakhstan declined before showing a modest gain in 2000. At present consumption levels, significant quantities of oil are available for export. During 2004, Kazakhstan exported 942,000 b/d of oil and condensate, and for the first 6 months of 2005, exports averaged 1.1 million b/d.

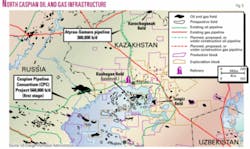

Current infrastructure delivers Kazakhstan oil to world markets in each cardinal direction: westward to the Black Sea via pipelines and rail, northward to Russia via pipeline and rail, southward through the Persian Gulf via swaps with Iran, and eastward through China via rail. An oil pipeline to China, linking the Kumkol fields in Central Kazakhstan to Western China, is currently near completion.

Three giants

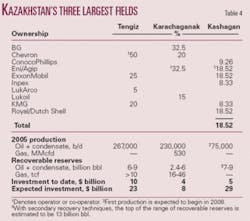

The majority of production growth in Kazakhstan is expected to come from four fields: Tengiz, Karachaganak, Kashagan, and Kurmangazy.

Tengiz and Karachaganak are producing; Kashagan is expected to start up in 2008; Kurmangazy is considered highly prospective but is still in the exploration phase. Kurmangazy is reported to have potential reserves of 5.5-7.7 billion bbl, but since the geologic structures have yet to be fully drilled, these values are considered speculative.

Karachaganak, Tengiz, and Kashagan account for the majority of foreign direct investment in the country (Table 4).

Tengiz field

The Tengiz field is located along the northeast shore of the Caspian Sea and is one of the largest and deepest oil fields in the world, lying three miles deep in a high-pressure formation underneath a half-mile thick salt dome (Fig. 5).

Originally discovered in 1974, Soviet engineers spent more than $1 billion before opening negotiations with Chevron to participate in the development.3 In 1993, Chevron and the new government of Kazakhstan formed a 50-50 joint venture to produce the field, and its capacity has been expanding incrementally, currently representing 21% of total daily crude oil and condensate output.

Tengiz recoverable oil reserves are estimated at 6-9 billion bbl. For the first half of 2005, the field produced 267,000 b/d oil and condensate.

Tengiz production is transported westward to the Black Sea port of Novorosiisk through the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) pipeline. Prior to the construction of CPC, the TCO consortium sought a variety of transit options to reach western markets, with about half of its production transported through the Russian pipeline system through Samara and the other half via railway to the Black Sea, to the Baltic, and to China.

A 3-year, $4 billion investment program for gas reinjection is expected to double production to 500,000 b/d by 2006, and according to company estimates, Tengiz could potentially produce 700,000 b/d by 2010. Total investment in Tengiz over 40 years is expected to reach $20 billion.

Karachaganak field

Karachaganak oil and gas-condensate field is located in northern Kazakhstan near the border with Russia’s Orenburg field (Fig. 5).

Considered one of the world’s largest gas-condensate fields, its production averaged 230,000 b/d during the first half of 2005, representing about 18% of total production in the country. Peak production is expected to increase to 500,000 b/d by 2010 under a significant investment program.

Prior to the construction of CPC, Karachaganak oil and condensate flowed north through Russian pipelines and was charged a significant premium on tariffs and a steep discount on sales, with prices estimated as low as 30% of world levels.13 After a link with CPC was completed in 2003, Karachaganak’s bargaining position and ability to reach world markets improved significantly.

Kashagan field

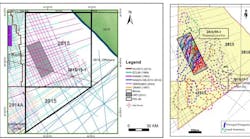

Kashagan field is located off the northern shore of the Caspian Sea (Fig. 5).

First identified by the Soviets in the early 1970s, the field was not drilled at the time due to the environmentally sensitive location, complex geologic formations, and high-cost environment. Comparable in size to Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, with geologic and hydrocarbon characteristics similar to Tengiz, the field is estimated to have recoverable reserves of 7-9 billion bbl of oil equivalent with potential estimated to reach 10-13 billion bbl using secondary recovery techniques.14 15

Kashagan’s first production is expected in 2008 at 75,000 b/d, achieving 450,000 b/d by 2012 and 900,000 b/d by 2013. By 2016, production is expected to plateau at 1.2 million b/d.

Kashagan is a large, complex, expensive, and technically challenging field development.16-19 The northern Caspian region is shallow and ice prone, and drilling is undertaken from artificial islands or draught barges (Fig. 6). The sea level can fluctuate dramatically and unpredictably, which causes logistical difficulties for service and supply companies.

The ecosystem is fragile and oil spills remain a constant threat (since the shallow waters would hinder-prevent dispersion). Ice hazards impact the area 4-5 months of the year, and the extreme temperature variations create special equipment and production requirements (Fig. 7).

The reservoir formation is deep (4,000-6,000 m below seabed), under a thick salt dome and abnormally high pressure, and gas production contains poisonous hydrogen sulfide that must be processed and reinjected. While gas reinjection is a well-established technique, the complexity of a sour gas re-injection at ultrahigh pressure requires a new technological approach.

Remaining sulfur needs to be disposed in costly enclosed or underground onshore storage areas, similar to operations at Karachaganak and Tengiz. The large areal extent of the field (75 km by 35 km) will require several hundred wells to efficiently extract the reserves.

The political risks at Kashagan are in a constant state of uncertainty. In 2001, the consortium consisted of BG (16.67%), Eni-Agip (16.67%), ExxonMobil (16.67%), Shell (16.67%), Total (16.67%), ConocoPhillips (8.33%), and Inpex (8.33%). Eni-Agip was elected the project operator and the consortium changed its name to Agip Kazakhstan North Caspian Operating Co.

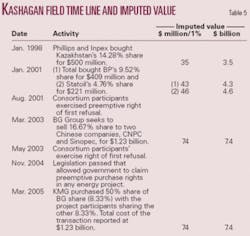

In 2002, a Declaration of Commerciality was made, and shortly after BG decided to divest its interest, the government staked a claim on the project assets. The final development plan for Kashagan was held up for nearly 2 years under intense negotiations while the government changed the law for state preemptive rights, allowing KMG to buy back into the consortium. The current imputed value of Kashagan is $7.4 billion (Table 5).

Gas production, consumption

Kazakhstan’s gas reserves are primarily associated with oil in free and dissolved form. Only small quantities of nonassociated gas-less than 2% of the gas reserves in the country-have been discovered.

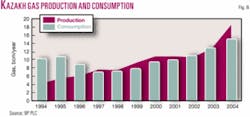

In 2004, Kazakhstan became a net exporter of gas, helped in part by legislation requiring companies to cease gas flaring (Fig. 8). A supply-demand imbalance remains in the country; however, since most gas is located in the west while future demand is expected in the south from Shymkent to Almaty.10

Small supply and limited demand make the construction of a gas pipeline network connecting the two regions uneconomic. Kazakhstan currently imports natural gas from Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan to satisfy demand in the southern part of the country.

Next: Recent developments in Kazakh E&P contracts, refined products, and pipelines.

The authors

Mark J. Kaiser ([email protected]) is an associate professor-research at the Center for Energy Studies at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge. His primary research interests are related to policy issues, modeling, and econometric studies in the energy industry. Before joining LSU in 2001, he held appointments at Auburn University, the American University of Armenia, and Wichita State University. Kaiser holds a PhD in engineering from Purdue University.

Allan G. Pulsipher is the executive director and Marathon Oil Co. professor at the Center for Energy Studies at Louisiana State University. Prior to joining LSU in 1980, he served as chief economist for the Congressional Monitored Retrievable Storage Review Commission, chief economist at the Tennessee Valley Authority, a program officer with the Ford Foundation’s division of resources and the environment, and on the faculties of Southern Illinois University and Texas A&M University. Pulsipher holds a PhD in economics from Tulane University.