Just days from the Environmental Protection Agency’s June 1 deadline for production of ultralow-sulfur diesel (ULSD) for highway vehicles, refiners and pipeline companies appear prepared for the changeover-but other downstream participants may not be ready.

The refineries of major integrated oil companies “seem to be very well prepared-in fact, much better prepared than you may think,” said Bob Shaw, energy director of BearingPoint Inc., McLean, Va., a management and technology consulting firm. “It’s some of the smaller players who are probably going to struggle to catch up.”

He said, “The closer to the refinery, the better prepared the participants are. The further downstream you go, the more challenges you’re going to face, particularly requirements for processing paperwork.”

Charles Drevna, new executive vice-president of the National Petrochemical Refiners Association, said: “Everything seems to be okay. That can either be good or it can be analogous to the guy who jumps out of a 30-story building and on his way down keeps repeating, ‘So far, so good.’ We’re cautiously optimistic, but we do have concerns.”

On the June 1 deadline, refiners “don’t have any choice,” Drevna said. “They’re either going to make it or they’re not going to ship any product.”

Adam Dreiblatt, senior manager of BearingPoint, said, “There definitely will be some walking on eggshells for the first few weeks.” Although ULSD soon will be reaching retail outlets, all of the potential glitches may not be apparent “until 6-12 months down the line when the reports start coming in.” By then, Dreiblatt said, “We may find out the industry wasn’t as prepared as it thought it was and that certain players in the industry don’t really understand the regulations and what it means to them.”

Mary Rose Brown, spokesperson for Valero Energy Corp., San Antonio, the largest US refiner, noted that the ULSD requirements will take effect in phases.

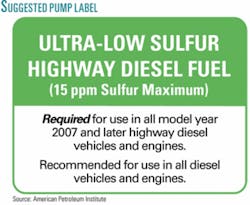

“Refiners have to begin making some ULSD (diesel with under 15 ppm of sulfur) by June 1 and need to produce an average of 80% ULSD and 20% LSD [low sulfur diesel with a maximum sulfur content of 500 ppm] within 13 months,” she said. “By utilizing the 13-month, 80%-20% average, we will meet the deadline.”

The industry consensus, however, is that ULSD will quickly account for 92-94% of all of road diesel produced in the US, Dreiblatt said. “The best estimates that we have seen-and EPA also agrees with-is that 90%-plus range of all diesel produced is expected to be ULSD by June 1,” he said. “The publicly stated 80% minimum is the lowest number EPA thought they could reasonably expect. They thought they were being especially generous to the industry to do that.”

Low specifications

The major concern among refiners is the low specifications imposed by pipeline companies on ULSD entering their systems.

“We’re going to have to shoot for 4-5 ppm inside the refinery so it will be no more than 7-8 ppm by the time it gets to the pipeline,” Drevna said. “When we’re down to those ultra, ultra, ultra low levels of sulfur, we’ve really got to have robust treatment, and we can’t afford any slip-ups. And, unfortunately, it’s going to take a heck of a lot more barrels of crude to make the same amount of fuel.”

How much more crude “depends on each refinery.” In reducing sulfur content to 500 ppm “or even 50 ppm,” a refiner “could use certain streams right out of the distillation tower to blend right in and get it,” Drevna said. But at specifications of 4-5 ppm, he said, “Those streams become unusable. There’s only three species of sulfur in the stream at those low levels, and those guys just don’t want to come out.”

Pipeline companies have said if ULSD does not meet their specifications at points of entry, they will downgrade it to LSD. Colonial Pipeline Co. and Olympic Pipe Line Co. each have specified a maximum 8 ppm for ULSD entering their systems. Explorer Pipeline Co. allows 8 ppm for ULSD received directly from refineries into its system, but drops to 7 ppm for ULSD originating in Lake Charles, La., and Port Neches, Tex. Buckeye Pipe Line Co. will take ULSD with up to 8 ppm from refineries and up to 10 ppm from connecting carriers. At Marathon Pipe Line LLC, the acceptable sulfur content depends on the source and delivery point.

More than 60% of all the petroleum products transported in the US moves through 200,000 miles of oil pipeline infrastructure, usually passing through several pipelines from refineries to final destinations. Each hand-off poses risks of contamination from valves, line flushes, and breakout tanks. Large-diameter and long-haul pipelines also provide more interface, which increases risks of contamination. The potential for all of that contamination must be estimated to determine pipeline entry specifications for ULSD.

Tests late last year by the Association of Oil Pipe Lines and the American Petroleum Institute indicated ULSD can pick up as much as 3 ppm of sulfur contamination between the certification tank and pipeline entry, while tank farms and hand-offs “continue to contribute 1-2 ppm each.” That study concluded potential contamination points would be identified and managed as pipeline companies gain experience in handling ULSD. But it also said dedicated ULSD infrastructure “should be considered” since “off-spec” distillate could “lock up” the distribution system, affecting gasoline and diesel supply. AOPL said its members are spending an estimated $500 million to minimize contamination.

The costs

The refining industry estimates that reducing the sulfur content of diesel to 15 ppm from 500 ppm will cost $9 billion, on top of the $8 billion spent to comply with Tier 2 sulfur gasoline requirements. “So just those two little sulfur rules in the past 4-5 years have cost $17 billion,” said Drevna. “We get tarred [on Capitol Hill] for having our members make decent profits [through higher pump prices in 2005-06], but they’re plowing those profits back in [to comply with government regulations].”

He said, “When [government] layers all of these regulations on top of each other and doesn’t sequence them, it’s asking the refining industry to do a lot. We’ve been putting the capital in, and everyone down the line-pipelines, marketers, terminals-are doing the best they can. But when you’re doing all these things at once, somewhere that rubber band is going to snap.”

Valero is adding new units, retrofitting others, and upgrading equipment at 15 refineries to meet the new USLD specification. Upgrades include new or upgraded hydrotreaters and hydrocrackers.

“For example, we are building two new mild hydrocrackers at Houston and St. Charles and new hydrotreaters at Memphis, Lima, and Port Arthur that are central to our ULSD strategy. These new units will be coming online from the middle of this year through early next year, and other projects will follow in 2007,” Brown said. “As we complete ULSD projects throughout our system, we will gradually increase our production of this clean-burning diesel fuel.” She said, “Across the industry, the refinery upgrades required to meet the ULSD specification have been delayed by the tight labor and materials markets along the Gulf Coast because of the back-to-back hurricanes [Katrina and Rita in 2005].”

Testing

Regulations require inspections at the point of refining or importation. EPA’s definition of refining includes “anyone who is combining or blending undesignated blendstocks to create diesel or heating oil,” said Dreiblatt.

Participants further downstream in the distribution chain are not required by law to test. “But they probably should,” Dreiblatt said. “There is a part of the program that is known as presumptive liability.” If an EPA inspection at a truck-stop diesel pump reveals a sulfur violation, the agency assumes that everyone upstream from the pump to the refinery is guilty of that violation. It is then up to every link of that distribution chain to prove its innocence. “One way to prove it is with a test result,” said Dreiblatt.

“Testing is part of a good quality-assurance program and a good defense against presumptive liability,” he said. “But you have to balance that against a cost of $1,200/test at times,” depending upon the extent of the tests. As a result, he predicted, “Most people at the service-station level aren’t going to be testing. But most people at the barge or bulk-transport level, import-ship level, are going to be testing individual compartments.”

EPA recently made concessions in terms of testing for the 15 ppm standard because of variability in the ability of the testing firms to produce accurate tests. A test firm using the latest equipment and the latest procedures should get the required level of repeatable precision in its testing. But if it is using other equipment or procedures, the variability is beyond what is acceptable, Dreiblatt explained.

“EPA went to a lot of different testing labs with standardized samples, and they came back with a big mess [in test results]. So they loosened some of the regulations on the variances of acceptable testing,” he said. “It’s not going to help if you’re pumping 500 ppm by accident into the wrong tank. But if you’re trying to do the right thing and there’s some leakage in the system, as there always is, or some commingling or transmix, as there always is, it allows you to not put a hold on that particular batch and take it out or recertify it.”

Downstream surprise

Surprises have hit “more-downstream parties” such as traders and terminal, barge, and truck companies. “The surprise has been just how much additional processing of paperwork they will have to do, as well as the surprise in this liability issue, which they haven’t faced before,” Dreiblatt said.

“Traders are faced with increased challenges, mainly from a reporting standpoint. They have some new regulations that the EPA has laid on them in order to support these rules and the ability to track the flow of product through the system. They need to be much more on top of documentation,” he said. He explained: “There are certain balances [traders] have to maintain. They’re only allowed to do certain amounts of activities in a given compliance period. The way the EPA has structured this program, it has put in a series of buffers that takes them over the course of several years, and the objective of that is to create some stability in the system to smooth the transition and avoid shortages or major price implications.”

According to EPA requirements, ULSD must reach distribution and marketing points-pipelines, distributors, terminals, and transporters-by Sept. 1 in most of the US and July 15 in California. The new ULSD requirements become effective Oct. 15 at retail outlets in most states and Sept. 1 in California. LSD fuel may still be sold at retail outlets outside of California until Dec. 1, 2010.

“As you go further down the chain, you have more players involved, the terminal companies, the barging companies, the jobbers, and then to a lesser extent the actual service stations just because they have a much lower level of requirement placed upon them,” Dreiblatt said. “That’s where you’re going to see some of the near to middle-term hiccups and issues.”

Because ULSD has to be segregated from other materials with a higher sulfur content, the already tight capacities of petroleum terminals and barges are going to get even tighter. Shippers “can’t do ‘cocktail barges’ as much anymore, with multiple products in different compartments,” Dreiblatt said. “With the shared infrastructure on the barge, there are dangers of contamination.” The problem is compounded by hurricane damage to barge facilities on the Gulf Coast in 2005 as well as replacement demand. “To build new barges is a several-year wait. It’s going to exacerbate any problems in terms of a tight distribution system. Any additional damage to barge manufacturing facilities in the gulf during the 2006 hurricane season would certainly push back some timeframes,” Dreiblatt said.

Market outlook

The new diesel engines in 2007 model vehicles, particularly commercial trucks, are driving the demand for ULSD because they can use only that fuel. “At first, only a small portion of the diesel engines on the road is going to need ULSD. But we need to have supply in enough places to offer that diesel to all of the new trucks,” said Dreiblatt.

Because ULSD is comparable to European grades, it is expected to increase sales of European diesel-powered passenger cars in the US. Earlier-model US diesel engines also can burn ULSD. “This is a supply-push initiative. The life cycle of a truck engine is maybe 20 years plus, so it takes some time for that to cycle through the system. In terms of a true [market] pull, it’s going to occur over the years as the new engines come into place,” Dreiblatt said.

Although ULSD will soon be the dominant highway diesel fuel produced, EPA does not require service stations and truck-stops to sell it. Therefore, it is possible ULSD initially may not be available at every service station or truck-stop and that a retailer may choose to sell only LSD.

ULSD also is expected to cost more than LSD at the pump, but no one is sure how much more it will be.

“Our industry is facing a major transition over the next few months so we could see some logistical issues that increase prices in the short-term,” said Valero’s Brown. “We could see some markets that really need ULSD pay higher prices to bring it to market, and we could see some batches of ULSD that are downgraded as a result of contamination while being transported or stored.” Any shortages “could be more geographic than nationwide,” said Drevna of NPRA. “If you’re a trucker pulling into a truck-stop along some interstate, and they don’t have the fuel you need, it doesn’t matter that the next truck stop 50 miles away might have it because you’re not getting there.”

He said, “When there’s a little bit of a gasoline problem, a shortage or prices go up, consumers complain and Congress gets irate and holds hearings. But when you don’t have enough fuel for truckers, you’re talking the economy. If they stop, everything stops.”