Gabe Collins, Naval War College, Newport, RI

Russia is taking a pragmatic new approach to the control of its energy resources. It is establishing new hybrid national energy companies, with state-owned PetroKremlin becoming an entirely new model of national energy company.

Because Russia is the world’s next energy superpower, it is crucial for consumers to clearly understand the evolving, unique structure of its energy industry.

Russia will not follow the OPEC path of 100% state-controlled companies. Instead, it will permit foreign investors to own up to 49% of the state companies through means such as the upcoming initial public offering (IPO) for state-owned oil and gas firm OAO Rosneft and the recent share liberalization of its national gas company OAO Gazprom. Under this system, the Kremlin can use foreign capital to maintain and possibly boost production and acquire competitors while preserving ultimate control over what may be the world’s largest combined oil and gas reserves.

The new model

While the country has become the world’s largest producer of combined hydrocarbons-each day producing the equivalent of 20 million bbl of oil-Russia’s largely state-controlled energy industry has been simultaneously developing along an unprecedented line.

The Russian government has decided to retain only a slim controlling stake in several large oil and gas companies while selling the rest to private investors. No other country having state-owned oil and gas companies and depending so heavily on oil and gas as levers of political influence has been willing to maintain so thin a margin of control.

By comparison, Brazil has been unwilling to sell more than 16.6% of its equity stake in Petróleo Brasileiro SA, and Norway, only 23.7% of Statoil ASA. Among other major producers, Iran, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, and others adamantly reject any privatization of their state oil companies.

Organizing oil and gas production along “51% state - 49% private” lines likely will strengthen the Russian state producers’ finances, and could greatly reduce their need for cash-rich, but reserves-poor Western partners.

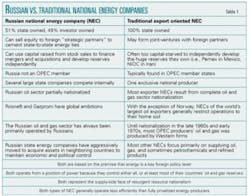

Table 1 outlines the differences between Russian and “traditional” state energy companies.

From the Kremlin’s perspective, this new structure is beneficial because the Russian state companies can use foreign capital to take over private competitors. In October 2005, Gazprom bought OAO Sibneft for $13 billion, which came primarily from a consortium of Western banks. The government can also use equity offerings to solidify international energy partnerships while retaining control of hydrocarbon resources.

OAO Rosneft is considering selling 20% of its OOO Yuganskneftegaz exploration and production unit to India’s Oil & Natural Gas Corp.1 China National Petroleum Corp. is also in the running for an interest in Rosneft and may have the inside track because Chinese banks lent Rosneft $6 billion in 2004 to enable it to buy Yuganskneftegaz.2

An additional benefit may surface once Western investors acquire large stakes in Gazprom and Rosneft; they may pressure their governments to take a softer line towards Russia. This has been the case in Sino-US relations, where the American business lobby has consistently advocated engaging China.

The Kremlin’s new approach is shrewd. It has the option of offering minority stakes in Gazprom and Rosneft and perhaps other companies if the state acquisition spree continues. The Russian government is willing to sell shares in these companies because by raising more capital they can escape the fate of companies such as Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) and National Iranian Oil Co. (NIOC), which sit atop rich reserves but are so capital-starved that they cannot even adequately fund their own projects.

Behavior changes

At the same time, large foreign share offerings may drive Russian state companies to change their behavior. After becoming 49% foreign owned, Gazprom is making two major changes. First, it recently announced a plan to restructure itself over the next 2 years to increase the transparency of its 17 affiliate companies that control 80% of the firm’s assets.3 Gazprom hopes that increasing its transparency will attract investment interest sufficient to raise its market capitalization by as much as 30% in coming years. As of May 5 Gazprom was the world’s second largest energy company by market capitalization ($289 billion), surpassed only by ExxonMobil Corp. (market cap: $386.6 billion).4

Second, Gazprom also has asked government regulators to permit it to raise its internal Russian gas price by 22% in 2007.5 The company currently sells gas at a loss within Russia. The price increase would create billions of dollars in additional revenue and may signal Gazprom’s shift toward a more market-based business model.

The emerging structure of the Russian energy sector also is unique because it promotes competition among several large state-controlled energy companies. The typical major energy exporter has established one state-owned oil and gas monopoly-for example, Pemex in Mexico or Saudi Aramco in Saudi Arabia. Struggles within these companies result from bureaucratic clan warfare within the Kremlin, as well as personal turf fights among company heads. For example, as the Kremlin debated what to do with OAO Yukos in 2004, it planned for Gazprom to absorb Rosneft. Rosneft’s management did not want to lose control of its firm, fought back fiercely, and ultimately succeeded in torpedoing the deal.

A Russian restoration

The idea of governments maintaining stakes in partially privatized energy companies is not new. The British government did not fully privatize British Petroleum PLC until 1995. Most governments with strategic shareholdings in a national champion energy producer tend to reduce their position over time as part of a gradual privatization. Britain and Canada took this path with BP and PetroCanada.

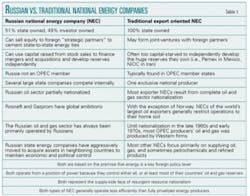

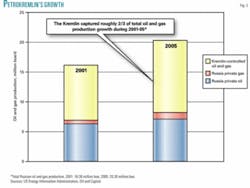

Russia has done the exact opposite. Since coming to power in 2000, President Vladimir Putin has worked to restore state control over natural resource industries that had been largely privatized after the Soviet Union fell. During Boris Yeltsin’s 8 years in the Kremlin, oil and gas assets were privatized in a “fire sale” that so undervalued them that simply gaining control of a field made the buyer instantly wealthy. In 1998, the Russian government came within a hair of fully privatizing Rosneft, which at the time was the last major state holding in the oil industry (Fig. 1).6

Two events signaled the partial reversal of privatization. First, Putin came to power and moved to rein in the oligarchs who now controlled most Russian oil production. Second, oil prices rose, encouraging the Kremlin to take a harder line in its dealings with foreign oil companies. Putin and his advisers recognized that foreign investors needed access to Russia more than Russia needed them, a fact made clear with the 2003 arrest of oilman Mikhail Khodorkovsky and the subsequent dismemberment of his firm OAO Yukos.

Prior to Khodorkovsky’s arrest, Yukos and other Russian oil companies had been expanding production at 8-9%/year by reworking existing wells and fields with the help of Western investors and service companies. President Putin and his advisers gambled that they could nationalize Yukos, reinforce state control of the oil and gas industry, and still attract much-needed investment from foreigners desperate for access to Russia’s oil and gas.

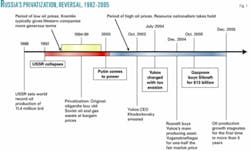

Fig. 2 shows the rapid growth in the Russian state’s share of oil production over the past 7 years.

The Kremlin’s strong push for renewed state control of the energy business is unsurprising. President Putin’s doctoral dissertation discussed using large state-controlled corporations to make hydrocarbons the cornerstone of Russia’s economy. Many of Putin’s most powerful advisers are siloviki (ex-KGB men) who vigorously advocate the state control of oil and gas resources. Indeed, the Ministries of Energy and Economic Development recently released a list outlining 40 key areas in which foreign investment should be restricted. The list includes “producing goods or delivering services as a natural monopoly” as well as “production of minerals considered strategic to the federal government.”7 Oil and gas resources fit this definition perfectly.

Putin and his circle jealously guard control of Russia’s natural resources because they see them as one of Russia’s few remaining sources of international power. This view has gained strength with increase in oil prices. Indeed, one of the key strikes against Yukos was that it was considering completely selling itself to a major Western oil company, which, in siloviki eyes, would have placed more than 1 million b/d of Russian oil production in foreign hands. This would have pried some of the Kremlin’s fingers off of the energy lever because a private company would not likely allow political decisions to take precedence over commercial ones. In this respect, Yukos’s plans to build private oil pipelines to China and to an export terminal at Murmansk were an example of the independent behavior that the Kremlin sees as a major threat to its position (Table 2).

null

Energy superpower

The Kremlin has greatly expanded its presence in the oil industry since Putin came to power. Both the Yukos and Sibneft deals were “forced” and had strong political overtones, as the low per-barrel acquisition prices attest. If the nationalization trend continues and Surgutneftegaz (1.28 million b/d) and the rest of Yukos (462,000 b/d) come under Kremlin control, PetroKremlin will be the world’s third largest national oil producer after Saudi Aramco and NIOC.

Measured in barrels of oil equivalent, Russia’s combined daily oil and gas production is double that of Saudi Arabia. Now, forceful acquisition of large oil reserves and production has given Moscow the “blocking stake” it needs to ensure that all future oil and gas projects are carried out with the Russian national interest fully in mind (Fig. 3).

Currently, the Russian state companies produce the equivalent of 12 million b/d of oil, making PetroKremlin by far the world’s largest state energy operation (and the world’s largest oil and gas operation). Even if the government allows foreigners to buy shares in the state companies, the Kremlin will have ultimate control of most Russian reserves, as well as the lion’s share of production and all oil and gas pipeline export routes. Under the emerging system, the Kremlin has control over the state companies, and, because it is the government, it also sets the rules by which all companies must operate, giving it further leverage over the Russian energy sector.

‘State capitalism’

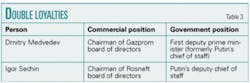

There are a number of key implications inherent in Russia’s move to “state capitalism.” First, the Russian state is becoming the ultimate oligarch. The “original” oligarchs are being shunted aside and replaced by a new bureaucratic oligarchy that frequently wears two hats. One is the state energy firm they run, and the other is their government office. Dmitry Medvedev is an excellent example. He is Gazprom’s chairman of the board-and also happens to be Russia’s first deputy prime minister. In July 2005, German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine estimated that Putin’s inner circle, many members of which are highly placed in the Kremlin, controls $222 billion in corporate assets, much of it in natural resources (Table 3). 8

Second, just like the old oligarchy, the new Kremlin oligarchy has many internal rifts. This makes Russia’s internal resource politics very complex, as shown by the struggle between Rosneft and Gazprom for Yuganskneftegaz and by Gazprom’s attempts to absorb Rosneft. State pipeline monopoly OAO Transneft also is a powerful domestic player because it controls all Russian oil export pipelines.

Rivalries between the Kremlin’s “energy dons” will have a serious impact in coming years if laws are not clarified and codified soon. Much of Russia’s substantial oil production growth during 1997-2004 came not from new fields but from workovers and applications of advanced Western practices and technology in existing fields. To replace reserves and maintain production, each Russian company urgently needs large investments in new exploration, drilling, and transportation infrastructure. A case in point: Sibneft produced 660,000 b/d of oil during 2005. This is forecast to drop to 346,000 b/d by 2010 in the absence of a major new investment program.9

With the long lead-time of most large new field developments, today’s investments will determine Russia’s production during 2010-15. Western firms will be wary of sinking too much capital into Russia until the government lays down a clear set of rules designed to attract investment. If the Kremlin does not quickly welcome new investment, its ability to deploy energy effectively as a foreign policy tool may suffer.

The new Russian business model could squeeze international oil companies very hard by reducing the Russian state firms’ need for cash-rich Western partners. If other major energy exporters follow the Russian lead, national energy companies worldwide may suddenly find that they can rely on capital markets and Western contractors rather than Western producing companies, which often want equity ownership in oil and gas. This realization could trigger further consolidation and restructuring of Western oil and gas producers.

References

1. Kolchin, Sergei, “Davos: Russia is Looking East,” RIA Novosti,” Jan. 31, 2006 (http://en.rian.ru/analysis/20060131/43262852-print.html).

2. Yenukov, Mikhail, “Rosneft chief wants to take $20 billion IPO global,” Reuters, Feb. 25, 2006 (www.reuters.com).

3. Reznik, Irina, “Gazprom Splits,” Vedomosti, Mar. 27, 2006.

4. “Gazprom Outlook is Looking Bright, Despite Politics,” The Wall Street Journal, May 5, 2006, C1.

5. “Gazprom Asks to Raise Gas Prices in 2007 by 22%,” (Gazprom Prosit Povisit tsenu na gaz v 2007 na 22%), Neft ii Kapital, Mar. 7, 2006 (www.oilcapital.ru/print/news/2006/03/071555_86585.shtml).

6. “Russia approves plan to privatize Rosneft” (OGJ, Dec, 1, 1997, p. 36).

7. “Window Rights,” (Oknoe Pravo) Kommersant, Mar. 2, 2006 (http://www.kommersant.ru/content.html?IssueId=30031).

8. “Frankfurter Allgemeine: Putin’s Inner Circle Controls Companies Worth $222 Billion,” Newsru.com, Economics, Jul. 27, 2005 (www.newsru.com/finance/27jul2005/fra_print.html).

9. Peznik, Irina, “Sibneft Underproduces,” (Sibneft ni Podkachaet) Vedomosti, Feb. 10, 2006 (http://vedomosti.ru/newspaper/print.shtml?2006/02/10/102743).

The author

Gabe Collins ([email protected])([email protected]) will join the Naval War College in Newport, RI, on May 30 as a research fellow. He is a 2005 graduate of Princeton University, where he earned a BA (cum laude) in politics.

Collins, who speaks Russian and Mandarin Chinese, lived and studied in Moscow and St. Petersburg, Russia, from June through mid-October 2005. He is a member of the International Association of Energy Economics.