RUSSIAN OIL EXPORTS-Conclusion: Expansion eyes multiple outlets

Eugene Khartukov

Ellen Starostina

Center for Petroleum Business Studies

Moscow

The vast majority of infrastructure projects in the Russian oil sector are aimed directly at increasing exports, the country’s ability to export currently constrained primarily by limited facilities.

This concluding article of a two-part series focuses on plans to increase exports through Murmansk and Angarsk as well as opportunities to export oil to the south.

The first article discussed overseas demand for Russian crude, Russia’s desire to export, and the status of plans for the Druzhba, Baltic, and Black Sea pipeline systems.

Murmansk plans

In Russia’s far north, all proposed oil-export projects gravitate towards passage to the Atlantic, which the Gulf Stream keeps ice-free. OAO Gazprom is pursuing a 300,000 b/d oil terminal at Pechenga, northwest of Murmansk, to serve the Prirazlomnoye oil field in the Barents Sea.

Gazprom also designed Northern Gateway, with a proposed capacity of up to 500,000 b/d, to facilitate oil exports from the Kharyaga, Northern Territories, and other upstream projects in the Nenets Autonomous District.

OAO Lukoil and ConocoPhillips, meanwhile, plan to expand the oil terminal at Varandey to 220,000 b/d.

The ambitious Murmansk project, proposed in November 2004 by Lukoil, Yukos Oil Co., TNK-BP, and OAO Sibirskaya Neftyanaya Kompaniya (Sibneft), overshadows these plans. The project, also backed by Surgutneftegaz, ConocoPhillips, Marathon Oil Corp., and Total SA, plans to construct a major pipeline to transport West Siberian oil to Murmansk for loading onto VLCCs at a new oil port. The pipeline would follow one of two proposed routes (either 1,600 or 2,200 miles) from the Tyumen oil fields to the ice-free port.

Participants originally projected the capacity of the system at 1.2 million-1.6 million b/d by 2008, costing $5.1 billion-$5.7 billion, with a possible later expansion of up to 2.4 million b/d. The Russian oil majors involved in the project, however, signed a memorandum of understanding with Truboprovodniy Transport Nefti (Transneft) and the Ministry of Energy, boosting the 48-in. line’s ultimate capacity to a projected 3 million b/d.

The participants allocated the line’s throughput as follows: 1 million b/d filled by Yukos, 660,000 b/d by Lukoil, 500,000 b/d by TNK, 400,000 b/d by Sibneft, and 240,000 b/d by SNG. The companies set aside a total of 200,000 b/d for third parties.

Pending conclusions of an energy ministry feasibility study, Transneft will build and operate the line by 2007.

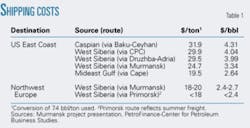

Although participants tout the advantages of this mammoth project in exporting Russian crude to the US, it could also facilitate less expensive oil exports to closer European markets (Table 1).

Transneft has also proposed a 290-mile pipeline be built from Kharyaga to Indiga by 2008. This pipeline and a new oil terminal at Indiga would carry 240,000 b/d and cost nearly $2.2 billion, according to Transneft. We expect, however, that this project will cost no less than $3 billion.

Angarsk alternatives

Future oil exports from Eastern Siberia have followed two conflicting plans. Both options are based on a pipeline starting from Angarsk (near the city of Irkutsk) but would end either in northeast China (Yukos’ proposal) or near the Russian Pacific port of Nakhodka, at Perevoznaya Bay (Transneft’s suggestion).

The Yukos-backed scheme takes the risk of locking oil from eastern Russia into the Chinese market but could be amply supplied by the region’s projected production (expected to reach 600,000 b/d by 2010).

Transneft’s plan-which Japan has actively lobbied for, offering Russia $5 billion in low-interest loans-offers the advantage of potentially diverse export destinations but also has a serious weakness: the lack of sufficient supplies in the region to support its 1-million-b/d minimum capacity.

Cost is another consideration. Yukos’ 1,420 mile, 40-in. pipeline would cost $2.2 billion, with China National Petroleum Corp. paying another $700 million. Transneft’s 2,410 mile, 48-in. alternative, wholly funded by the Russians, would cost an estimated $5.8 billion.

The Angasrk-Nakhodka pipeline would be nearly three times as long as the Trans-Alaskan Pipeline and would traverse terrain nearly as harsh, causing many analysts to doubt the official cost estimates and suggest an $8-11 billon price instead.

In May 2004, the Russian cabinet tentatively approved Yukos’ plan to build the Angarsk-Daqing pipeline, supplementing it with a leg to Nakhodka if East Siberian and Yakutian oil supplies become sufficient to fill both the branches.

A 26-year supply deal between Yukos and CNPC further cemented the pipeline. A total of more than 5.2 billion bbl of Russian crude would move to China during the course of the deal, starting with 400,000 b/d in 2005-09 and increasing to 600,000 b/d in 2010-30.

The Russian government, however, indefinitely postponed a final decision on the project. In an effort to meet interim Chinese demand, Russia has promised to increase rail deliveries to China to 6.5 million tpy.

The Russian government most recently seems to have decided that the 1-million-b/d pipeline will run from Taishet (500 km north of Angarsk) to the Pacific, with a 1,400-mile leg from Skovorodino, near the Chinese border, to Daqing. But as yet unresolved environmental issues will likely push completion past the November 2008 date targeted by Transneft.

Southern passage

Transneft has also talked with Kazakh pipeline operator KazTransOil JSC regarding shipping 100,000-200,000 b/d of West Siberian crude through the recently completed pipeline from Kazakhstan to China at a basic tariff of $16.10/ton (around $2.20/bbl). The 640-mile line, with projected capacity between 600,000 b/d and 1 million b/d, runs eastward from Atasu (halfway between Pavlodar and Shymkent on the Omsk-Chardzhou pipeline) to Druzhba (Alashanku) on the Kazakh border with China’s Xinjiang province, targeting oil refineries at the western end of the Chinese pipeline system (Dushanzi and Urumqi).

The pipeline is a part of an ongoing project aimed at bringing crude oil from western and central Kazakhstan, including the northern Caspian, to both the country’s underutilized eastern refineries (Pavlodar and Shymkent) and western China. Construction of the 1,740-mile Atyrau-Kenkiyak-Kumkol-Atasu-Druzhba pipeline is underway at an estimated cost of $2.7 billion.

The Atasu-Druzhba section, commissioned in December 2005, cost $850 million.

Export-driven output

Ongoing and envisioned projects will boost the export capacity of major Russian outlets (wholly or partly available for Russian crude) to more than 7 million b/d by 2007 and 10.2 million b/d by 2010, from 5.5 million b/d in 2004 (Table 2).

Russia will not use all the incremental capacity for its own crude, sharing it with Kazakhstan and other central Asian exports rather than using foreign facilities.

Adding minor export facilities (rail, river, and small sea terminals), estimated at another 1.0-1.2 million b/d, provides a fairly reliable forecast of Russia’s total crude oil exports outside the FSU reaching 5.9-6.1 million b/d by 2007 and 8.7-8.9 million b/d by 2010. Adding domestic demand for crude oil at a projected rate of 4.1-4.2 million b/d, plus net exports inside the FSU at a probable rate of 0.9-1.0 million b/d, leads to the conclusion that Russia’s crude oil output (including field condensate) will reach 10.9-11.3 million b/d in 2007 and 13.8-14.1 million b/d in 2010.

Until Russia’s oil resources are depleted, it seems certain that available export capacity will determine its production growth. Russian oil companies will produce as much crude as they can profitably export.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Yakov Ruderman (PetroMarket Research Group), Aleksey Aleksandrov (RF Ministry of Energy), Mikhail Tigashov (TransNafta), Sabr Yessimbekov (KazTransOil) and Tamara Varava (UkrTransNafta). ✦