RUSSIAN OIL EXPORTS-1: Projects focus on pipeline, terminal expansions

Most major infrastructure projects in the Russian oil sector are directly aimed at increasing oil exports. Despite officially declared export cuts, the country continues to boost its crude supplies by rapidly debottlenecking existing export outlets and building new ones.

Russia will export as much oil as it can. Its ability to export crude oil, however, is currently limited by available export facilities. The country’s major crude export capacity (pipelines and seaports) has reached 5.5 million b/d. In 2004, Russia used only 3.3 million b/d of this with the balance ceded to Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Belarus through intergovernmental agreements. With more export facilities being commissioned, however, Russia will have more capacity to export its crude.

The most important oil export projects include further development of the Druzhba and Baltic pipeline systems, as well as new construction of the Murmansk oil hub and Angarsk (East Siberian) pipeline.

This article, the first of two, discusses overseas demand for Russian crude, Russia’s desire to export, and plans for the Druzhba, Baltic, and Black Sea pipeline systems.

The second article will focus on Murmansk and Angarsk, as well as opportunities to export oil south.

Enigmatic exports

In the heyday of Soviet oil exports (the late 1980s), the USSR exported up to 2.9 million b/d of crude, mostly a special blend known as Urals with an API gravity of around 32° and 1.8% sulfur. Urals flowed through the Druzhba pipeline to Eastern Europe. Soviet oil ports on the Black Sea (Novorossiysk, Odessa, and Tuapse) and on the Baltic Sea (Ventspils) also exported Urals. Other minor crude oil streams moved to foreign destinations by rail, mainly to China, and through seaports in the Russian Far East.

After the breakup of the USSR in late 1990, Russia lost full control of pipeline outlets to Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary as well as the Ukrainian port of Odessa and Latvia’s Ventspils. The Russian oil pipeline monopoly Transneft, however, retained control of the crude oil flowing through these outlets, as the export pipelines continued to be fed chiefly by Urals.

After a while, other ex-Soviet republics (such as Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Belarus) started using the Transneft-controlled pipelines to export their crudes and also started building new pipelines (e.g., the Caspian Pipeline Consortium line from Kazakhstan to the Black Sea) and terminals (such Butinge on Lithuania’s Baltic Sea coast). These actions broke the formerly indivisible Soviet export of crude oil to outside the ex-USSR into three main streams:

• Russian crude exports to outside the FSU.

• Russian crude supplies exported inside the FSU (mostly to Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan).

• Non-Russian crude flows (chiefly from Central Asia, Azerbaijan, and Belarus) through the Transneft-controlled network to both non-FSU destinations and other ex-Soviet republics.

Although Transneft distinguishes between its oil shipments within and outside the Commonwealth of Independent States, with the Baltic ex-Soviet republics being regarded as outside destinations, Western observers are more accustomed to calculating how much crude is exported by Russia (and other ex-Soviet countries) beyond the borders of the FSU.

Overseas demand

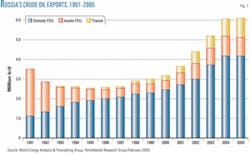

The market-related terms of new sales contracts, which the former Soviet satellites in Eastern Europe had to accept, initially impeded Russia’s crude exports to non-FSU destinations. These terms, however, affected the virtually insolvent ex-Soviet economies, which could now afford only a modest fraction of their former imports of Russian crude (Fig. 1), to a far greater extent.

Total exports of Russian crude shrank from 3.5 million b/d in 1991 to less than 2.5 million b/d in 1995. Russia’s supplies to other ex-Soviet republics plummeted from 2.4 million b/d to 600,000 b/d over the same period. Russian oil, now at market prices, had lost its formerly subsidized ex-Soviet buyers.

Demand for Russian crude from buyers outside the FSU, which was also initially somewhat depressed, has steadily recovered and now exceeds its 1988 record level of 2.9 million b/d. Crude oil transit by non-Russian ex-Soviet states reached some 1.0 million b/d in late 2005, while figures from the late 1980s were aggregate Soviet numbers.

Russian exports could have grown even faster than this were it not for infrastructural bottlenecks, as the domestic oil market has suffered from persistent over-supply since 1993.

Russia’s annual oil output is driven by its need for oil export revenues. These oil exports are the only reliable source of income for the Russian oil companies.

Although oil-related hard currency revenues are not as important to the general Russian economy as to most OPEC economies, they support a still fragile system. Exports of crude oil and oil products account for roughly one-third of Russia’s export revenues. The oil sector generates about 15% of Russia’s GDP, while oil-related taxes account for as much as 25% of federal budget receipts. The Russian government cannot afford to sacrifice even a fraction of those revenues for the sake of supporting world oil prices.

Druzhba’s return

The Druzhba pipeline remains the main export artery for Russian crude, handling up to 1.3 million b/d. Its northern branch (900,000 b/d) feeds Poland and Germany, while the southern branch (400,000 b/d) exports to Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and the former Yugoslavia. Dropping oil demand in Eastern Europe, however, has reduced the volumes shipped through the pipeline. The Druzhba’s average capacity utilization rate in 2005 was around 85%, with its southern leg carrying only 80% of its nameplate capacity.

The Druzhba’s southern utilization should grow when the 35-in. Adria pipeline, starting at Omisalj, Croatia, is reversed to ship Russian crude to the Adriatic. This scheme, proposed by Yukos Oil Co. and backed by Tyumen Oil Co. (TNK), aims to increase capacity to 300,000 b/d by 2010. The reversal will cost $20-30 million, while the expansion to 300,000 b/d will require up to $320 million.

Croatian pipeline operator Janaf completed reversing its section of the Adria pipeline in 2004. The implementation of various safety and environmental requirements added around $60 million to the project’s estimated cost. The project was also delayed by the disagreement between Transneft and its Ukrainian counterpart OJSC UkrTransNafta, which insisted on concluding direct contracts with Russian oil producers shipping their crude along the Druzhba-Adria route.

These problems were resolved, and the line started operations in late 2004.

The Odessa-Brody pipeline linked the Druzhba’s Ukranian section to a new oil terminal at Pivdenny, 25 miles northeast of Odessa, in August 2001. The 420 mile, 40 in., 180,000-b/d line can be expanded to 900,000 b/d and extended by 190 miles to the Polish refinery at Plock. The Brody-Plock extension would require 2-3 years to build and cost $300-500 million, in addition to the $160 million or more already invested in Odessa-Brody.

The plan is vigorously supported by Ukraine, as well as Poland, Germany, and the EU, but none of them is keen to fund it. The extension can materialize only if UkrTransNafta, which runs the still-idle Odessa-Brody line, secures Caspian supplies to and from the Black Sea to Plock and, further, through the Pomeranian pipeline to the Baltic port of Gdansk.

The first signs of actually using the Odessa-Brody link for northern transit were shown by Kazakhstan’s state oil and gas holding company KazMunaiGaz, which pledged to conduct a feasibility study on using an extension to Plock to ship up to 160,000 b/d of Kazakh crude through Pivdenny.

Several Russian oil majors (including Lukoil, Yukos, and TNK) have persuaded the Ukrainian government to reverse the Odessa-Brody line temporarily to pump Russian crude through the Pivdenny terminal for seaborne export. The firms’ desire for additional oil exports seemed to justify a relatively high tariff for the line of $4.30/ton ($0.60/lb), plus an additional fee from the Belarus border to Brody of $2.30/ton.

Since the start of 2003, TNK, TransNafta, and ANK Bashneft have used a short (32-mile) southern fragment of the pipeline between Michurinsk and the 840,000-b/d Pivdenny terminal in reverse. In late August 2004, under pressure from Russia, Ukraine agreed to allow Russian companies use of the Pivdenny outlet for up to 80,000 b/d of crude, starting in fourth-quarter 2004, possibly signifying the end of Ukranian resistance to reversal of the Odessa-Brody pipeline.

This export route through Pivdenny has also attracted those Kazakh exporters who had masked their intentions by talking about the Plock extension. In late July 2004, KMG succeeded in convincing UkrTransNafta of the need to lay a parallel 32-mile Michurinsk-Pivdenny line for shipping Kazakh and Russian crudes. Kazakhstan also offered to build a new berth at the terminal to handle its crudes. According to KMG, this would keep the Odessa-Brody line free for its original mission: pumping oil northward.

Meanwhile, Polish pipeline operator PERN plans to invest around $200 million to increase the flow of Russian crude to the Naftoport oil export terminal in Gdansk. The terminal operates at only a fraction of capacity because of constraints imposed by the Druzhba pipeline.

PERN will spend most of the money building a new line along the northern branch of the Druzhba pipeline from the Belarus border to Plock, which is connected with Gdansk by the Pomeranian pipeline. The 145-mile Adamowo-Plock line, which would boost the capacity of the Druzhba’s northern leg to nearly 1.3 million b/d from the current 900,000 b/d, could be completed in 2006.

Another possible route for Russian exports is the Ingolstadt-Kralupy-Litvinov pipeline, connecting Germany’s Ingolstadt refinery with Czech refineries at Kralupy and Litvinov. IKL’s operator, MERO CR, has proposed using half of the pipeline’s 200,000-b/d capacity in reverse, to pump up to 100,000 b/d of Russian crude to western Germany, instead of using it to supply Czech refineries with Mediterranean crudes. Yukos is interested in the scheme but has yet to persuade the Czech and German refiners to make the switch.

After acquiring a 49% stake in Slovak pipeline operator Transpetrol in late 2001, Yukos expressed its interest in building a Bratislava-Schwechat pipeline, connecting the 115,000-b/d Bratislava refinery in Slovakia with Austrian OMV Aktiengesellschaft’s 180,000-b/d Schwechat refinery near Vienna, currently supplied through a pipeline from the Italian port of Trieste.

In August 2004, Yukos and OMV agreed to build the pipeline, with an initial capacity of 72,000 b/d, potentially rising to 100,000 b/d. To keep the $30-million line busy, Yukos also pledged up to 100,000 b/d of Urals crude for an initial 10 years, starting at 40,000 b/d in January 2006.

Baltic expansion

The Latvian port of Ventspils remained the main outlet for Russian crude destined for North European markets until recently. In 2002, Transneft, which seeks an inexpensive controlling stake in the port, embargoed it. If Transneft succeeds in its effort (its most recent ultimatum having expired in May 2005), the current 320,000-b/d capacity of the outlet could be expanded to 360,000 b/d.

As an alternative to an independent Ventspils, in late 2001 Transneft built its own Baltic oil terminal at Primorsk on the Gulf of Finland northwest of St. Petersburg. Transneft has expanded its original capacity to more than 1.2 million b/d from 240,000 b/d, but its continued use depends on market conditions, especially any resurgence in oil exports from Iraq.

The first phase of the Baltic Pipeline system to Primorsk, including a new 40 in., 240,000-b/d pipeline from the Kirishi refinery, cost Transneft some $600 million ($140 million more than planned). The almost-completed second phase, which would boost capacity of the BPS to 840,000 b/d, includes a longer 40 in., 600,000-b/d line from Palkino (near Yaroslavl), for up to $1.4 billion.

If the fairly heavy ice conditions at Primorsk undermine its use, Transneft has a standby plan to build a 160,000-b/d pipeline from Primorsk to the more easily accessible port at Porvoo, Finland.

With the takeover of Lithuania’s AB Mazeikiu Nafta by Russia’s Yukos, the Lithuanian port of Butinge, built in 1999, is also available for Russian oil exports. Moreover, the Lithuanian government has proposed expanding the port’s export capacity to around 250,000 b/d from the current 165,000 b/d, with Yukos responding by offering to finance expansion to 280,000 b/d.

Developing Lukoil’s new terminal at Vysotsk will also boost Russia’s oil export capacity in the Baltic. Lukoil completed the first 50,000-b/d phase of the projected 220,000-b/d export terminal, 18 miles north of Primorsk, at the end of 2004, with about 140,000 b/d on stream by end-2005. Although the $300-million project was designed primarily to ship dirty oil products, Lukoil reserved some 50,000 b/d of its capacity for crude oil, with an initial 20,000 b/d of crude export facilities operating at the start of 2004.

Black Sea

Transneft is pushing ahead with plans to increase trans-shipment capacities at Novorossiysk, which can handle more than 900,000 b/d. A projected boost to 1.2 million b/d is likely during 2006. Capital requirements for this project, involving expansion of feeding pipelines, range as high as $1.2 billion.

Unlike Novorossiysk, the terminal at South Ozereyevka is constrained by a lack of Russian crude supplies. The Caspian Pipeline Consortium built the offshore loading facility 15 miles northwest of Novorossiysk in mid-2001 to facilitate seaborne exports from Kazakhstan’s Tengiz oil field. The 40 in., 940-mile line, which has cost more than $2.6 billion, was originally to ship up to 1.4 million b/d, about 350,000 b/d of which was to be Russian crude made available by a planned inter-connection with Transneft’s pipeline to Novorossiysk.

The connection line could be quite short (30-60 miles) and built within a month for no more than $50 million. Potential suppliers of Russian crude, however, found the interlink option too expensive to use (at more than $1/bbl of additional tariffs), and in September 2002 CPC scaled down planned capacity to 1.13 million b/d. This option, however, remains open.

In the meantime, however, CPC capacities will increase to 1.06 million b/d in 2006 from the current 560,000 b/d and to 1.42 million b/d by 2014, requiring additional investment of $1-1.3 billion, including $250-300 million from Russia. The Russian government, which has a 24% stake in CPC, insists on raising the line’s tariff to $38/ton ($5/bbl) to make the pipeline profitable, if less than competitive.

To make the Black Sea picture complete, Russia’s interest in joining the recently completed Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline should be noted. In late July 2005, the Kremlin asked the Russian energy ministry to analyze a plan prepared by JSC Rosneftegazstroy to build a connection line between the port of Novorossiysk and the Georgian section of the BTC. Heavy Bosporus traffic has prompted this consideration, despite resentment in some corners of the Russian government regarding the competition posed by the BTC line. ✦

The authors

Eugene Khartukov is general director of the Center for Petroleum Business Studies, Moscow; vice-president (Eurasia) of Petro-Logistics, Geneva; head of World Energy Analysis & Forecasting Group; director (international affairs) PetroMarket Research Group, Moscow; and professor of management and marketing at Moscow State University of International Relations. He graduated with honors diploma (1977) in international economics from MGIMO; obtained a PhD (1980) in international and petroleum economics and post-doctorate (professorship; 1990) in international and energy economics, both from MGIMO, and since 1994 holds the lifetime title of professor. He is a member of Council of Energy Advisors (US) and the Russian Association for Energy Economics.

Ellen Starostina is head of PetroFinance Consultancy and director for finances of Center for Petroleum Business Studies, Moscow; and is an international consultant on oil finances and taxation to trading companies, commercial banks, and law firms. She graduated from Moscow-based Plekhanov Academy of National Economy (Faculty of National Economy Planning) in 1981 and obtained a PhD (2002) in petroleum finances and taxation from the same institution. In 2003, she joined the Council of Energy Advisors (US).