Refiners to see strong returns near-term despite looming capacity buildup

Aileen Jamieson, Wood Mackenzie, Edinburgh

null

Overcapacity and associated low margins are an unlikely outcome of 66 announced grassroots refinery projects.

Current speculation that the world is running short of refining capacity is concerning in the industry. Long-term forecasts for high crude prices (greater than $50/bbl) and higher-than-normal refining margins are helping boost investment in the industry and investor confidence in the sector.

At the end of January 2006, about 500 refinery projects (including 66 grassroots refineries) had been announced, with many more probably being considered in-house. This revival of investment is largely due to flourishing margins and concerns of a global shortage of refining capacity.

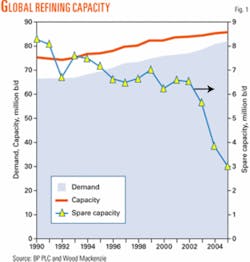

Only a few years ago, refining was a low-returns business, with refiners struggling to rationalize overcapacity. Indeed, refiners would have been lucky to make a $1/bbl margin on sweet crude in Europe or Asia.

Investor appetite in the refining sector has been transformed and asset prices have risen with it. In the unlikely event that all the refining capacity additions come on stream as announced, however, the refining industry could return to a position of overcapacity and low returns. But the question is what is the risk of this occurring?

Wood Mackenzie conducted a study to assess each refinery project’s chances of actually being built. The net result is that many of the announced projects will probably not be built and the industry will retain its current tight capacity.

Regional dynamics show that strong demand growth across the barrel in Asia Pacific will soak up extra capacity coming on stream. Indeed, significant additional crude capacity may be required just to keep pace with demand.

In the US, the changing makeup of the crude barrel is as important as the growth in total demand; therefore investment will be required in both upgrading and additional crude capacity.

Europe, on the other hand, where demand is approaching maturity, requires no significant additional crude capacity. The changing demand barrel, however, is stimulating investment in upgrading capacity.

Understanding the future requires far more than a simple comparison of global demand growth against incremental crude capacity.

Time to invest?

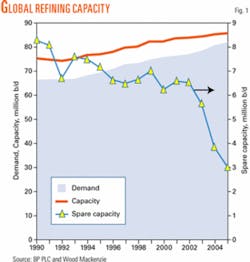

Fig. 1 shows that spare global refining capacity has been on a continuing downward trend, which has accelerated since 2002. Crude distillation capacity increases have not kept pace with the demand growth for oil products.

In 2002, spare refining capacity was around 7 million b/d; in 2005 we estimated this had fallen to less than 3 million b/d, an unprecedented level. In the 1980s, spare capacity peaked at close to 19 million b/d, and the historic previous lowest spare capacity was 3.3 million b/d in 1965, a completely different era. Correspondingly, refining margins have increased.

null

Regional developments

The decision of where to add capacity, however, requires a solid understanding of regional developments because local dynamics vary markedly.

• Timing is key. In Asia, strong demand growth is “mopping up” surplus refining capacity and major refinery building programs are already underway in China and India.

The speed at which India is proposing to add capacity, however, could result in overcapacity in the short-term at least. On the other hand, in China it is doubtful that refiners will be able to build capacity quickly enough to satisfy rapidly growing demand.

• Grassroots capacity unlikely. The US continues to experience a deficit in refining capacity and last year’s hurricane damage further highlighted the situation.

It remains difficult to build a new refinery in the US, however, due to current legislative and environmental regulations. In fact, the last grassroots refinery was built in 1976. The US therefore depends heavily on imports of oil products, particularly gasoline.

• Product imbalances dominate. Europe has a burgeoning surplus of gasoline and an increasing deficit of middle distillates.

Although Europe overall is relatively balanced in total oil products, a chronic imbalance continues between the supply and demand of individual products.

• Hugely underutilized. Russia’s refining system has historically been hugely underutilized, and while rationalization has reduced capacity significantly during the last decade Russia still has surplus refining capacity.

Although growing domestic demand may reduce future exports of product from the region, the key requirement is to increase upgrading capacity in the country, rather than adding crude capacity.

• Export driven. Middle Eastern refiners, as well as investing to meet growing domestic demand, are once again actively examining the merits of export refining.

Furthermore, it is imperative to remember that given the scale and long-term nature of the business; there are no short-term solutions. Lee Raymond, former CEO of ExxonMobil Corp., said in recent testimony to the US Senate (OGJ, Nov. 21, 2005, p. 24), when considering grassroots refinery projects, “current refining economics are almost irrelevant.”

With the length of time it takes to design, build, and commission a new refinery, refiners will need the confidence of solid margins over the long term before sanctioning a project. Perhaps, as ExxonMobil believes, a more practical and economical way to add crude capacity is to develop existing facilities selectively.

Finally, history should be a guideline. The Asian financial crisis in 1997-98 caused a dip in demand that coincided with a surge of new capacity coming on stream. Spare capacity soared and led to 5 years of depressed margins.

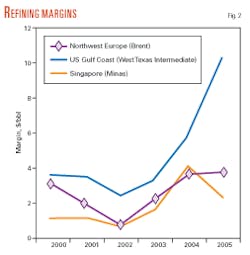

If all 66 grassroots refineries come on stream in the next 10 years as announced, there would be an additional 12 million b/d of crude distillation capacity. This is in addition to the 70 expansion projects in existing refineries; all-in-all an increase of 18 million b/d (Fig. 3).

This is substantially more than our forecast of oil demand growth of about 15.7 million b/d during the next 10 years. Clearly the timing of investments is key to ensuring that the industry does not return to a position of soaring overcapacity.

Back to reality

Of the 500 announced investment plans, about 140 are to increase refinery capacity (either expansions or grassroots capacity). A similar number of plans are for increasing upgrading capacity-hydrocrackers in Europe and Asia and delayed cokers in the US-and more than 180 projects are for quality compliance (to meet tightening fuels specifications).

Not every refining investment that is announced actually comes to fruition. For example, governments in developing economies may announce grassroots refineries that are simply not economic but are announced for political reasons. Furthermore, for some countries, obtaining reliable and accurate information on current infrastructure and future refinery investment plans can be difficult.

To identify the probable global supply developments, Wood Mackenzie therefore assesses investment plans against these key project fundamentals, which indicate the project’s viability and therefore its likelihood to proceed:

• Current project status (planning, engineering, under construction).

• Project rationale (economic opportunity, product-quality specification compliance, or other).

• Alignment with projected regional supply-demand balances.

• Location (brownfield or grassroots site, access to low-cost feedstock, proximity to demand centers, pre-existing infrastructure, etc.).

• Sponsor capabilities (access to funds and proven project development capabilities).

We ranked each of the 500 announced investments as strong, medium, or weak.

Strong projects are well aligned with correcting regional trade imbalances, thusly converting surplus products into those that are imported. Examples include capacity additions in Asia and residue upgrading to middle distillates in Europe. Strong sponsors, in general, have the experience and technical capability required to develop major refining projects and have access to financing.

Medium projects may be poorly aligned with a local region’s trade balances but well aligned with developments in adjacent regions. Examples include projects in North Africa targeting European deficits and the Middle East targeting Asia. Medium-ranked sponsors may not have secured financing yet, and, although they have the certain internal capabilities to develop projects, they rely upon extensive support from others for implementation.

Weak projects are poorly aligned with a region’s trade balance and rely on developments in distant markets. Examples include export-oriented refineries in Africa targeting the US. Weak sponsors are likely to have limited previous project experience, limited “in-house” capabilities, and funding constraints.

Our analysis and experience suggests that most, if not all, of the projects we have ranked as strong will proceed, around half of the medium-ranked projects will occur, and only 10-15% of the weak projects will reach fruition. We can therefore apply this analysis to the announced capacity additions to produce a more realistic capacity addition forecast.

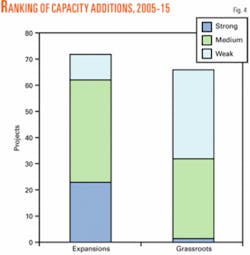

Fig. 4 shows the number of projects that have been announced for both expansion of existing sites and grassroots capacity and our rankings for each.

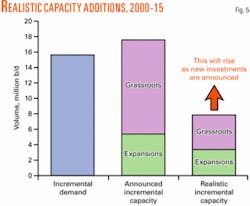

Fig. 5 shows the realistic capacity additions. It shows that the realistic global crude capacity additions (about 8 million b/d) are significantly less than what is needed to meet the growth in global demand. This suggests that further investment in new capacity will be required but does not necessarily mean that more of the currently announced projects (that we have ranked as weak) will occur.

The reality is that new investment plans are announced almost daily, and therefore more capacity is expected than shown above from “strong” projects that have not yet been announced, particularly after 2010, due to the time lag between inception and commissioning of new projects.

Furthermore, the regional picture is critical, not just the global view. Although balancing incremental capacity against incremental demand is important in such markets as the Middle East and Asia Pacific where product growth is expected across the barrel, in more mature markets, such as Europe, it is more important to balance the supply and demand of individual products.

Regional analysis

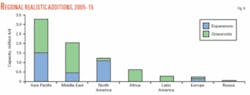

Based on our global refinery investments database and our methodology for ranking projects, we analyzed where realistic regional capacity may be added (Fig. 6).

As expected, the bulk of capacity additions will be built in Asia Pacific (where the greatest demand growth is forecast) and the Middle East (both for domestic consumption of oil products as well as for export).

Perhaps surprising is the size of the anticipated increase in capacity in North America. Although current legislative and environmental regulations make it difficult to build a new refinery in the US, we anticipate that more than 1 million b/d of capacity will be added via expansions in existing sites.

Key projects in each region include:

• Asia Pacific. The improvement in margins since 2003 has stimulated many new expansion and grassroots refinery projects, principally in China, India, and Thailand. The supply-demand fundamentals will support strong margins into the next decade because demand growth will continue to outpace the capacity additions and the refining balance will tighten further. Almost half of the additional capacity in Asia Pacific will come from expansion of existing sites.

• The Middle East. There are fewer expansion plans in the Middle East; instead these refiners are concentrating on building new, large (400,000 b/d), export-oriented refineries that can meet fuels legislation in the relevant export markets.

National Iranian Oil Co. and Saudi Aramco are planning to expand existing sites; Aramco is expanding to integrate with world-class petrochemicals complexes. The strongly ranked grassroots refineries in this region are in Yanbu and Jubail.

• North America. Arizona Clean Fuels LLC is planning to build the first grassroots refinery (150,000 b/d) in the US since 1976. The remainder of capacity additions in the US will be expansions at existing sites.

Motiva Enterprises LLC announced it is considering expansion plans of 100-325,000 b/d at one or more of its three refineries. ConocoPhillips Co. announced that expansion and upgrade projects are being planned at 9 of its 12 US refineries.

Marathon Oil Corp. announced that it will “essentially build an entirely new refinery” at the Garyville, La., site. This will add 180,000 b/d to the existing 245,000 b/d refinery (OGJ, Jan. 2, 2006, p. 11).

Due to these expansions, plus a number of smaller expansion plans, US crude capacity will increase more than 1 million b/d-the equivalent of five new world-scale grassroots refineries-in the next decade.

• Africa. None of the announced projects in Africa has been ranked as strong, mainly due to funding constraints and lack of strong sponsors. In general, two or three new refineries may be built in North Africa (Algeria, Libya, or Morocco) to serve the Mediterranean market as well as meeting internal demand growth.

• Latin America. There are only a small number of expansion plans announced in Latin America; the bulk of new capacity planned is in grassroots refineries.

In particular, Petróleo Brasileiro SA and Petróleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA) are planning a joint venture, 200,000-b/d refinery in Brazil. PDVSA plans to build three more refineries in Venezuela (one in Cabruta at 400,000 b/d); however, it is unlikely that these Venezuelan projects will come on stream before 2015.

• Europe. Although three new refineries have been announced in Europe (Spain, Portugal, and Turkey), the supply-demand fundamentals and prevailing refining economics will make such investments challenging. Europe currently has a slight surplus of refined products but by 2015 could balance.

As a mature market, Europe does not need more crude capacity; rather it needs more capacity to produce middle distillates to meet the ever-growing demand for jet fuel and diesel.

Two significant refinery expansion plans are being implemented in the Mediterranean, however. Compañía Española de Petroleos SA and Repsol YPF SA are increasing crude capacity at their Huelva and Cartegena refineries, respectively. These expansion plans are ranked as strong because they are part of a wider investment project (including hydrocrackers and cokers) to increase middle distillate yields.

• Russia. Little is planned for expansion of crude distillation capacity in Russia. The Russian refining system has historically been hugely underutilized and rationalization has reduced capacity significantly during the last decade. Given the substantial capacity overhang, we do not anticipate significant crude-distillation expansion plans and much of the future investment in refining will be directed at increasing the yield of higher-value distillate products. ✦

The author

Aileen Jamieson (energy@ woodmac.com) is a managing consultant for Wood Mackenzie, Edinburgh. She joined Wood Mackenzie’s downstream consulting team in 2001, specializing in crude quality, refining, and oil product supply. Jamieson has been involved in detailed analyses of refining and forecasts oil product supply-demand balances for Europe, US, and Asia Pacific. Before joining Wood Mackenzie, she worked for ExxonMobil Corp. for 5 years in both technical and commercial roles. Jamieson holds a BEng (1996) in chemical engineering from Edinburgh University.