Comment: EU may miss Kyoto targets despite EEA recommendations

At a roundtable organized by major Italian environmental group Legambiente, Romano Prodi, Italy’s 1996-98 prime minister and current leftist candidate for that same position, described himself as a “Kyoto fighter” or advocate of the Kyoto Protocol on Climate Change.

As president of the EU [European Union] Commission in 1999-2004, Prodi had strongly supported the climate treaty-even playing a key role in Russia’s decision to ratify the protocol-so most Italian media emphasized his commitment to emissions reduction. Yet as an economist, Prodi went further and added: “Economic recovery comes first.”

Implicit in the latter statement is the recognition that there may be a tradeoff between economic performance and the pursuit of environmental protection policies in the EU. While often ignored or even denied in Europe, such truth helps to explain why the EU is falling short of its goal to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide to 8% below 1990 levels.

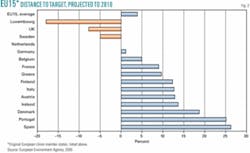

According to the European Environment Agency’s (EEA) projections, the EU will miss its objective by 6.4 percentage points and achieve just one fifth of its original target.

Despite such a poor performance, the EU can still reach its goals as long as it undertakes “savings from additional measures,” “the use of Kyoto mechanisms by various member states,” and “overdelivery by some member states,” says EEA. Historical data and projections under various assumptions are shown in Fig. 1.

Such optimistic forecasts are far from credible, however. The Kyoto Protocol was accepted in 1997, but most reductions observed so far were achieved before that date and were due to events that had little or nothing to do with efforts to mitigate global warming. In fact, emissions in most of the original 15 EU members (EU15) have risen since 1999, except for a modest reduction achieved in 2002 (see Fig. 2 for EU15 members list). In 2003, EU15 emissions were just 1.7% below the baseline year.

According to EEA, the major drivers behind the 2002 reductions were “warmer weather in most EU countries which reduced the use of carbon dioxide-producing fossil fuels to heat homes and offices” and “slower economic growth in manufacturing industries.” Consistently, emissions rose the next year because of, among other reasons, “colder weather in the first quarter in several EU countries.” Paradoxically, therefore, global warming looks like an antidote for itself: the more temperatures increase, at least in the winter, the faster emissions fall.

Under existing measures, emissions are projected to stabilize at the present level, which is well distant from the target. Yet EEA claims that an 8% reduction is still possible. While the burden of proof in such a claim-which contradicts a well-established trend-relies on EEA itself, the agency’s suggestions to achieve the Kyoto goals are unrealistic at best.

The first recommendation is a truism. Of course emission targets can be met through “additional measures.” EEA doesn’t identify which measures, however. More importantly, the fact that something is technically possible doesn’t mean it is economically feasible. For instance, suppose the EU passed mandatory caps on national emissions. Once the allowed level is reached, power plants and industries would be shut down, public and private lights turned down, and streets closed to traffic. It is unlikely that such a policy would ever be adopted; yet those are precisely the kinds of “additional measures” needed to significantly cut energy consumption.

The second and third suggestions go hand-in-hand: The Kyoto mechanisms, however appealing, can’t work for the simple reason that a country needs someone able to sell emission quotas if it wants to buy any. Unfortunately, most European countries will not emit less than what they are allowed under the burden-sharing agreement, through which they have internally redistributed the Kyoto-mandated cap.

EEA itself admits that just three countries, the UK, Sweden, and Luxembourg, are on track to comply with the Kyoto protocol. They account for 15.6%, 1.7%, and 0.3% of EU15 emissions, respectively. Thus only the UK can provide a substantial contribution to lowering the price of emission quotas by being a big supplier.

By the same token, it is unlikely that there will be over-deliveries by enough member states to significantly change EU15’s performance. The 10 new member states that joined the EU on May 1, 2005, will probably meet their own goals. However, their emissions are increasing, so the contribution they can give to the EU bubble target will decline and possibly could be offset by future economic growth.

Last exit

The last exit to Kyoto is the reliance on the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), through which an industrialized country can invest in a project undertaken in a developing country and claim credit for the emission reductions achieved (OGJ, Feb. 4, 2004, p. 18).

The CDM rationale is that, because what matters ultimately is total global emissions-no matter where they are generated-it makes sense to locate projects where they are cheaper.

Despite initial opposition from the EU, the CDM may be helpful in terms of cost-effectiveness. The CDM is mostly about transferring renewable sources of energy, such as wind and solar power, to poor nations. Renewables generally are more expensive than hydrocarbons, even though some local exceptions may exist.

Economic repercussions

Investing in developing countries, as well as buying emissions allowances abroad or reducing emissions domestically, is not without costs. Several estimates have been offered on the Kyoto Protocol’s economic impact on Europe. According to general equilibrium and macroeconomic models, Kyoto will cost EU15 nations 0.5-2%/year less GDP in 2010.

The International Council for Capital Formation, Brussels, released a study of four major EU countries: Italy, UK, Spain, and Germany. Compliance with the Kyoto Protocol would cause GDP to shrink by 2.1, 1.1, 3.1, and 0.8%/year respectively, in 2010, with massive job losses and a dramatic increase in the cost of energy.

Such efforts would result in little or no benefit to the global environment. The science behind Kyoto is uncertain, and it is still unclear how much the emissions from human activity may impact global climate compared with natural causes well beyond human influence. The EU15 accounts for less than 20% of global emissions. Thus, should Europe succeed in its efforts, global emissions would decrease by less than 2%.

Moreover, as developing countries’ emissions rapidly grow with their economies, the European contribution to global emissions will be less and less significant.

Thus, the unilateral enforcement of the Kyoto Protocol can’t pass a cost-benefit analysis, because the benefit would be so small that no cost would be small enough to make the strategy profitable.

Faced with its incumbent failure to meet its targets, yet feeling the need to wave the Kyoto flag, Europe took two further steps: First, it made even stricter commitments by aiming at a 20-30% reduction under the baseline year by 2030. The costs of such a reduction would be dramatic, especially as almost no progress has been made so far.

Secondly, at the climate conference in Montreal last November-December, the EU followed the recommendations of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and insisted that the 2001 Marrakech Accord initiated in Morocco be adopted as a “compliance regime for the Kyoto Protocol.”

Under Marrakech, a party that doesn’t meet its target (as will probably be the case with the EU in 2012) not only has to comply with stricter targets in the following term but also can’t engage in emissions trading. For European countries this might mean that there would be no trading with non-EU parties, although intra-EU trading would still be allowed. The cost of compliance might then skyrocket.

Such a rule makes negotiations for Kyoto’s second commitment period all the more difficult. By insisting on Kyoto, Europe apparently ignored the forward steps taken at the G8 Gleneagles meeting in Perthshire, Scotland, in July 2005, where emphasis shifted from targets and timetables to technological innovation and global participation in an effort to address the challenges of climate change.

True, the Montreal climate meeting somehow found a way to partly neutralize the binding nature of Kyoto-Marrakech through a softening of enforcement mechanisms, but the Kyoto logic is still there.

Despite efforts made at the G8 summit and the viable exit strategy offered by the American-led Asian and Pacific Partnership on Clean Development and Climate Change, which might offer a plausible excuse for the EU to give up Kyoto, Europe is still insisting there is no real alternative to legally binding agreements. However, Europe is simply not on track to comply with Kyoto, so it is going through one of two possible scenarios in the next few years.

On the one hand it might buy “hot air” from countries such as Russia, India, and China, with little or no actual reduction in global emissions. This is possibly the only way to meet the targets, although at a huge cost for European industry and consumers. On the other hand, Europe might simply miss the targets, as EEA’s projections indicate. Missing the targets may negatively affect European credibility in the international politics. The alternative may be to maintain credibility by giving up economic growth, however. If that is the real trade-off that Europeans are facing, they might seriously consider their leaders’ credibility a convenient price to pay. ✦

The author

Carlo Stagnaro (carlo.stagnaro @brunoleoni.it) is environmental director of Italian free-market think tank Istituto Bruno Leoni (www.brunoleoni.it). He also is a fellow of the International Council for Capital Formation, Brussels (www.iccfglobal.org). Stagnaro, an environmental engineer, has written extensively on environmental and energy issues, including global warming, climate policies, and the integration of the European energy market. His articles have been published in a variety of newspapers, including Il Foglio and Il Riformista (Rome); Finanza & Mercati (Milan); TechCentralStation (Washington, DC); Economic Affairs (London), National Post (Toronto), and Schweizer Monatshefte (Zurich). His latest book is Più energia per tutti (2005), edited with Margo M. Thorning.