CENTRAL ASIA OIL AND GAS-2: Russian-Chinese competition may marginalize US, European influence

This is the second of two parts on the growth of Chinese energy investment in Central Asia, which has traditionally fallen within Russia’s sphere of influence.

China’s involvement in Uzbekistan’s energy sector is less extensive than in Kazakhstan, but the handful of Chinese investments in the most populous state in Central Asia are perhaps more important from a geopolitical perspective.

Uzbekistan status

Until June 2005, Chinese energy investments in Uzbekistan were largely limited to drilling equipment.

However, CNPC and Uzbekneftegaz, the Uzbekistan state oil and gas company, signed a $600-million deal to create a joint venture to develop 23 oil fields in the region around Bukhara and Khiva. UzCNPC Petroleum, which will operate over a 25-year period, is expected to raise annual oil production at the group of fields to 1 million tonnes (20,000 b/d) by 2015.

Quickly following CNPC’s investment deal in Uzbekistan was a $106-million deal between Sinopec and Uzbekneftegaz in July. The monetary sum in the agreement was fairly tiny by industry standards-requiring Sinopec to spend $50 million to rehabilitate aging oil fields in Andizhan and Namangan provinces and $56 million on exploration in the same region.

However, this deal, in conjunction with the earlier CNPC agreement, appeared designed to drive home a more significant point about strengthening Uzbek-Chinese political ties following the Uzbek government crackdown against a citizen uprising in the eastern city of Andizhan on May 13, 2005. The Andizhan massacre, which the Uzbek government claimed was a necessary use of force against rebels, resulted in more than 700 deaths, according to human rights groups and independent reports.

Despite international condemnation of the events of May 13, the Uzbek government has resisted calls from the West for an independent investigation. China’s muted response to the Uzbek government’s heavy-handed tactics in Andizhan signaled China’s willingness to accept the official version of events, while the Sinopec and CNPC investments in the aftermath of the apparent massacre provided the Uzbek government with much-needed international political cover.

CNPC’s participation in an international consortium that signed a gas exploration deal in Uzbekistan in September 2005 confirms China’s growing commitment-both in terms of economic trade and political support-to the Uzbek government.

The September agreement, covering the Ustyurt plateau and Aral Sea basin in western Uzbekistan, also includes Russia’s Lukoil, Malaysia’s Petronas, and South Korea’s KNOC, in addition to Uzbekneftegaz, giving the Uzbek government a greater base of political support in Asia to fend off pressure from the West over the Andizhan massacre.

Turkmenistan work

China’s interest in Turkmenistan’s energy sector is the least well-established relationship that the Chinese government has fostered in Central Asia, and given the geographical distance between the two countries perhaps the most curious.

Although Chinese companies have been operating in Turkmenistan on well workovers and upgrades, a July 2005 bilateral governmental energy sector cooperation deal signaled an intensification of China’s interest in Turkmenistan’s voluminous gas reserves, in particular. While Chinese companies are poking around Turkmenistan’s Caspian shelf for potential upstream development projects, China’s top focus in Turkmenistan appears to be gaining access to Turkmen gas reserves in the eastern part of the country.

CNPC has been rumored as a potential partner for Bridas in the Argentine company’s attempts to re-establish its rights to the Keimir oil field and the Yashlar gas field in Turkmenistan, but China is likely less interested in securing a stake in upstream Turkmen hydrocarbon projects than with actually delivering Turkmen energy exports to China.

Turkmenistan is keen to diversify its gas export options and thus reduce Russia’s economic and political leverage over the country, so China’s interest in Turkmen gas is finding enthusiastic support in Turkmenistan. Already, Turkmen President Saparmurad Niyazov has announced plans to sign a gas supply deal with China this year that would see Turkmenistan deliver 30 bcm/year of gas-this despite the absence of any gas pipeline infrastructure linking Turkmenistan to China.

A potential new gas pipeline linking Turkmenistan to China via Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan is estimated to cost $10 billion and take 6 years to build.

Competitors or collaborators?

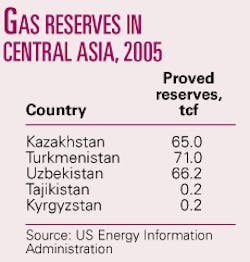

Looking at China’s growing involvement in the energy sector in Central Asia (Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have no significant oil or gas reserves, so China has focused its attention on the countries with greater hydrocarbon potential), it is interesting to note the “Russian response” to the burgeoning challenge to its position as the unquestioned arbiter of power in the region.

Will Russia sit idly by and allow China steadily to erode Russia’s influence in Central Asia, or will the Kremlin (Russia’s presidential administration) take greater steps to cement Russia’s preeminence? Thus far, it appears that Russian energy companies, with the strong backing of the Russian government, are taking a defensive approach to the issue by going on the offensive.

Considering that they share the world’s longest land border, as well as the collective history of the Soviet experience, Russia and Kazakhstan are natural partners in the energy sector. The “partnership” has been largely one-sided for much of the post-Soviet era, however, as Russia controlled Kazakhstan’s access to oil markets.

The commissioning of the CPC pipeline in 2001, giving Kazakhstan its first direct access to world oil markets (albeit via Russia), accelerated Kazakhstan’s development into an oil power of its own, and the country’s rapid expansion of oil production-along with plans to triple output to as much as 3.5 million b/d by 2015-has served to alter Russia’s perception of Kazakhstan.

Fundamentally, the relationship is still heavily weighted in favor of Russia, but Kazakhstan’s upstream potential has given it more leverage, and Russian oil and gas companies are no longer ignoring Kazakhstan.

Lukoil, Russia’s top oil producer, continues to expand its operations in Kazakhstan. Lukoil has stakes in two of Kazakhstan’s largest oil and gas projects, including a 2.7% share in the consortium developing Tengiz oil field and a 15% stake in the BG-led group that holds the rights to the Karachaganak oil and gas-condensate field in western Kazakhstan. In addition, Lukoil has a 50% stake in the Turgai Petroleum joint venture, which was producing approximately 73,000 b/d from the North Kumkol field in early 2005 before being forced by the Kazakh government to curtail output to reduce emissions from gas flaring.

Lukoil also holds the rights to several Caspian oil blocks in the Kazakh sector of the Sea, and the Russian oil major is slated to develop several fields in the North Caspian jointly with Kazmunaigaz in line with an intergovernmental agreement on their Caspian border.

In the gas sphere, Russia’s Gazprom has devoted greater attention to ensuring that it controls Kazakhstan’s embryonic gas industry, seeking to direct gas production from Karachaganak field to the Orenburg gas processing facility across the border while steering Kazakh gas exports into the Russian gas pipeline system.

Russian state-owned Rosneft is also lined up to play a role in Kazakhstan with its participation in the development of the 7.33 billion bbl Kurmangazy field in the North Caspian.

Perhaps the best indication that Russia is feeling the pressure of China’s focus on Central Asia-and reacting to it-is Lukoil’s hurried announcement in October 2005 of its plans to buy Bermuda-based Kazakh producer Nelson Resources Ltd. Although Nelson produces only about 30,000 b/d of oil and has reserves of 270 million bbl of oil equivalent in Kazakhstan, Lukoil moved quickly to snatch the company in the aftermath of CNPC’s acquisition of PetroKazakhstan.

The rapid-fire successive investments in Kazakhstan by CNPC and Lukoil suggest that further consolidation of the relatively fragmented Kazakh oil industry is in the cards and that the Russian and Chinese companies will be competing directly with each other for the next asset on the block.

Likewise, Russian companies have boosted their presence in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan in the face of China’s entry in the region. Lukoil has led the way among Russian companies in Uzbekistan, securing a key $1 billion gas deal to develop the Kandym group of fields in the Bukhara-Khiva and Gissar regions in June 2004.

Gazprom has taken a keener interest in Uzbekistan in the past 3 years as well, putting aside some previous animosity with the Uzbek government and Uzbekneftegaz to sign upstream development deals for the Shakhpati gas field in the Republic of Karakalpakstan in northwestern Uzbekistan and the Ustyurt plateau.

Gazprom has also contracted to buy Uzbek gas exports, and the company is expected to sign a formal production-sharing agreement (PSA) for the Urga, Kuanysh, and Akchalak group of fields in Uzbekistan this year after inking a preliminary agreement in January.

A poor investment climate, along with some residual hostility from the 1997 gas dispute between Turkmenistan and Gazprom, has largely kept Russian energy companies at bay in Turkmenistan. Still, both Lukoil and Gazprom have made strong approaches to the Central Asian country, although Lukoil’s back-door attempt to grab a stake in Turkmen oil production via UAE-based Dragon Oil failed.

An additional Russian-led investment in Turkmenistan by the Zarit consortium (made up of Rosneft, Itera, and Zarubezhneft) has repeatedly had its plans to sign a PSA for oil blocks in the Turkmen sector of the Caspian Sea postponed.

Signs of tension

With Russian companies clearly taking a greater interest in Central Asia in recognition of China’s nascent involvement, there is a growing sense of competition between the two countries.

The CNPC-PetroKazakhstan deal put Lukoil and CNPC together as uneasy bedfellows in the Turgai Petroleum joint venture in Kazakhstan, while Lukoil’s acquisition of Nelson Resources made the Russian company a partner of CNPC in North Buzachi field.

The fact that both Lukoil (in the case of Turgai) and CNPC (with North Buzachi) asserted their preemption rights to prevent the other from buying into their project speaks volumes about the emerging rivalry between the two firms, as well as between the Russian and Chinese governments in their policies towards Central Asia.

Cooperation possible

On the other hand, CNPC and Lukoil, as torchbearers for their respective governments, could set an example by dropping their preemption claims and deciding to work together as partners at Turgai and North Buzachi.

Cooperation between the firms is not outside the realm of the imaginable, as the fact that both companies are slated to participate in the same Aral Sea gas exploration joint venture in Uzbekistan attests. Moreover, any tension between the Russian and Chinese governments in Central Asia could be diluted by the increasing direct Russian-Chinese governmental cooperation in the energy sector.

Russia plans to build the first stretch of its Siberia-Pacific oil pipeline to the Chinese border by 2008, and Gazprom is continuing to hold talks with Chinese officials on an eventual gas supply deal between the two countries. Also, Kazakhstan could be a uniting factor rather than a source of division between Russia and China, as there is talk that Russia will use the Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline to deliver oil exports to China while waiting for the Russia-China pipeline to come on stream.

The prognosis

With China seeking energy resources in Central Asia and therefore currying political and economic favor with countries in the region, the key question is whether Russia and China can coexist in Central Asia.

Russia usually does not take too kindly to challenges to its authority (witness the recent gas dispute with Ukraine), and with the erosion of Russian influence in Eastern Europe, the Baltics, and now even Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova, Central Asia is one of the last remaining outposts of Russian domination.

Thus far, China and Russia have avoided locking horns in the region, and cooperation between the two countries has been enshrined in the regional security grouping of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which also includes Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

With the first real clash of the titans coming between Lukoil and CNPC over their investments in Kazakhstan, Gulnara Karimova, the influential daughter of Uzbek President Islam Karimov, suggested last month that the SCO expand its mission to include cooperation in the energy sector, thus ensuring that any Russian-Chinese energy competition in Central Asia would remain benign in a larger context of solidarity.

The SCO may yet adopt an energy sector role, but the smart money is on Lukoil and CNPC conducting an asset swap in Kazakhstan to free themselves of their newly acquired partners. Lukoil and CNPC will likely be happier-and more willing to cooperate in the future-if they aren’t forced to work together in their inherited projects.

The Central Asian countries stand to benefit from the increased attention from both Russia and China, provided that they can balance out investments from both countries. So long as Russia and China do not turn Central Asia into a new battleground for political influence but instead keep their focus on economic opportunities, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan should experience a rising level of energy investment from Russia and China.

The development of additional export options for Central Asian oil and gas production would be an encouraging result of China’s focus on the region’s energy reserves, but the combined weight of Russian and Chinese energy investments could serve to further marginalize US and European political influence in Central Asia, which is already secondary to the neighboring powers.

The fallout from the Andizhan massacre has put a chill on US-Uzbekistan relations, prompting Karimov to kick the US out of an Uzbek airbase in Karshi-Khanabad, while Russian and Chinese support for the Uzbek government has hardened the lines between the West and the Central Asian state.

Although the US and European governments and IOCs enjoy a relatively good relationship with Kazakhstan, relations with Turkmenistan are severely strained. Kazakhstan’s growing sense of power from its emergence as a major global oil producer was highlighted by recent efforts to secure a greater state role in the Kazakh oil industry.

The likelihood that this streak of nationalism will only be exacerbated as output continues to expand, and new export options become available to Kazakhstan, should serve as a warning shot across the bows to the West and the IOCs. ✦