Conventional wisdom and short-term memory strongly influence oil-market analysis. Recent trends and events influence most forecasts, no matter how sophisticated our econometric models.

When the oil-price trend is flat or declining, oil-price forecasts tend to be flat or rising gently. When the oil price is rising, price forecasts tend to be a steeply rising curve.

In a tight market, as at present, we thus tend to forecast strong growth in demand, become skeptical about the production capability of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and even about world oil reserves, and see inevitable crises ahead.

The question that needs to be asked, now as always, is whether short-term trends—analyzed in the first article in this two-part series—will endure in the longer term (OGJ, Jan. 24, 2005, p. 20).

Oil demand trends

In the 1950s and 1960s world oil consumption grew rapidly. At that time, it was expected that those rates would be maintained with the continuation of economic growth in industrialized countries, and more importantly, with the rising population and increasing aspirations of developing countries. Had those growth rates continued, world oil demand would have already reached unsustainable and explosive levels.

Almost 40 years later, the reality has proved to be different. The explosion in world oil demand did not occur. The growth was much slower, and in some years demand actually declined: 1974-75 and 1980-83 (Fig. 1). The declines were so impressive that security of demand became a great concern for oil producers.

Each of those demand slowdowns followed spikes in the price of oil. Analysis of Fig. 1 makes a similar demand response to the present oil price spike almost certain, though the response would not be as large since the price is not high in real terms.

High prices and public policies (especially in the industrialized countries) proved very effective in arresting oil demand growth in the 1970s and 1980s. Tangible factors include:

- Energy and oil conservation.

- Increasing efficiency of oil use in industry and households.

- Substitution of oil by other energies.

- Subsidies and tax exemptions for oil conservation and the production of other energies and prohibition of oil use in some sectors.

The main question today is whether future growth in world oil demand will match the high rates experienced in the 1960s and in 2003-04 or ease back to the low rates experienced for most of the last three decades. The 2003-04 growth rates might tempt us to think of the former. However, a more realistic assessment would suggest the latter.

Economic restructuring

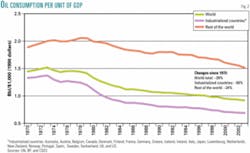

A result of energy and oil policies in the last 30 years has been a restructuring of the global economy and less reliance on oil. For the world as a whole since the early 1970s, there has been a nearly 40% reduction in oil consumption per unit of gross domestic product (GDP) in real terms (Fig. 2). The reduction has been most impressive (about 50%) for the industrialized countries. It has been smaller (24%) for the rest of the world. Overall, world economic growth is now much less dependent on oil than it was a generation ago.

The actual level of oil shown in Fig. 2 deserves study. On an aggregate basis, oil consumption per unit of GDP fell from about 1.5 bbl to 0.9 bbl for the total world. However, while it fell from about 1.4 bbl to 0.7 bbl in the industrialized countries, it fell from about 2 bbl to 1.5 bbl in the rest of the world.

This important comparison shows that great potential remains for the reduction of oil use in the world outside the industrialized countries. This potential is realistic since it has been achieved in many countries already. Oil consumption per unit of GDP in the rest of the world could decline from about 1.5 bbl at present to less than 1 bbl in the future.

Industrialized countries are also carrying on with their public policies to reduce oil consumption. Any recent complacency due to low oil prices is disappearing. A reduction is likely in the purchase of vehicles that consume fuel at high rates. Energy conservation, oil substitution, and other measures are being encouraged, and policies encouraging them are being reintroduced. High prices themselves will suppress oil demand.

Oil-importing developing countries have followed and are continuing to follow similar energy and oil policies. As in the industrialized countries, their oil-using capital and consumer goods are now more fuel-efficient, the utilization of natural gas is expanding, and other measures are continuing. Yet their GDP cannot grow to any significant extent, and oil demand growth due to the income effect will be moderate. The gap between the rich and the poor has widened, and the harsh realities of the world unfortunately do not favor the developing world. In practice, on a macroeconomic level, developing countries' investment, production, and exports cannot rise except at low rates. Consequently, the growth of their energy and oil consumption will be low.

The recently spectacular rise in oil demand in China thus might not continue. Questions have been raised about sustainability of that country's very high economic growth rate, the overheating of the economy, high inflation, the migration from the agricultural regions to the slums around the cities, the dangers of economic collapse, and social disorder. China is still a command economy and under central planning. Chinese authorities are already trying to control development, limit economic disparity, and avoid social and political crises.

For example, credits have been reduced for industrial plant expansion and for car purchases. Coal use continues, and natural gas production, imports, and pipeline construction are expanding. Already, data indicate a slowing of the economy and the moderation of oil demand.

Worldwide, oil has already been substituted in many sectors. Alternative sources of energy and renewables have been under development for a few decades; some have been successful in various sectors of the economy. Bulk heat generation is no more reliant on oil for producing electricity and for industrial activities.

Oil, however, remains the dominant fuel for the transportation sector, and most forecasters expect this to continue in the coming decades. While these forecasts might make oil producers complacent, the possibility exists of a technical breakthrough for liquid fuels derived from sources other than oil. In that case, the oil monopoly in the transportation sector could be broken.

Many other options exist already and have been subjects of research and development and pilot scale tests. The costs are high but have been greatly reduced. Some might have even become feasible with the recently high oil prices.

The world's reliance on oil and growth in world oil demand thus might not last forever.

The reserves debate

The debate over when the world will run out of oil has continued for many decades. Some believe world oil reserves will soon be exhausted. Others believe that market incentives will encourage technical ingenuity and innovation and that more oil will be discovered and more will be extracted from existing fields and new discoveries.

Unfortunately, the debate between the two groups has become too emotional and rhetorical in recent years. One side refers to the other as optimists, flat-earth believers, and wishful thinkers. The other side refers to the first as pessimists and alarmists crying wolf.

Recently, the alarmist views have attracted greater attention following news of the high price of oil and questions about reserves reported by Royal Dutch/Shell. In fact, both groups are correct—but in different contexts and according to different definitions.

Industry professionals experienced in the difficulties of finding, developing, and estimating oil and gas reserves tend to be conservative—or realistic, as they might say. They have performed a service in drawing attention to the question about when oil production might peak and are not scaremongers.

Many analysts in the more-optimistic group lack operating experience. They draw their conclusions from economic theory and observations of the outstanding technical achievements of the first group. And they expect those achievements so continue.

It is possible that the first group has become a victim of its own success and has created expectations increasingly difficult to fulfill.

Key estimates

The US Geological Survey (USGS) has estimated the world's total oil resources—produced so far and available by 2030—at more than 3 trillion bbl. About 1.4 trillion bbl of this volume will be added in the next 3 decades. Nearly half of this addition will be new discoveries, and the rest will be reserves growth in known oil fields.

The first group sees the USGS figures as exaggeration and estimates the total resource at about 2 trillion bbl, while some other analysts tend to accept higher figures in between. Conducting another study of world oil supplies would require a team of qualified professionals, access to world geological and petroleum industry data, and obviously sufficient funds and time for the research work.

A study of Iraq by CGES and Petrolog in the late 1990s lends support to the optimistic view. The team's estimate of Iraq's undiscovered oil resources is much greater than that by the USGS. If one can take the Iraq case as an indicator for the rest of the world, then global oil resources could be even greater than the USGS estimates.

Another very qualitative reason for optimism on future world oil supplies is the great volume of sediments that exist around the world's continental margins and extend down to the oceanic floor. These remain almost unexplored. Furthermore, not all the sedimentary basins in the world have been explored in detail.

Even the already known and explored sedimentary basins on land and offshore should not be discounted. The possibility of pleasant surprises and new discoveries cannot be ruled out. Such pleasant surprises in recent years have been quite encouraging, as in the Middle East, Caspian Sea, West Africa, and even onshore India (the Rajastan discoveries are small but indicative of the possibilities). These could continue in coming years.

Furthermore, the USGS estimates are for conventional oil. Extending the definition to all hydrocarbon liquids would make the estimates larger. The broader definition would include heavy and extra-heavy oil, tar sands, and natural gas converted to liquids.

Studies by the first group take a skeptical view of these sources of liquid hydrocarbons. And they provide strong arguments for the caution. For example, there should be no euphoria for the future of Canadian oil sands. Forecasts by Canada's National Energy Board are for an increase of 700,000-1 million b/d in the supply of synthetic oil and blended bitumen by the middle of the next decade. Most of this increase would be needed to compensate for the decline in production of conventional light and heavy oil. Canada's total oil production would increase only marginally between 2004 and 2015. Nevertheless, the total from all such sources in different parts of the world could become significant.

In any case, the most important point—and the critical issue in this debate—over the long-term is not the limitation of oil supply but the future of oil demand.

Reserves exaggerated?

The recent downgrading of reserves by Shell and other companies might be interpreted as an indication of the limitation of world oil resources. Such interpretation is misleading since this issue has been more a question of definition, categorization, auditing, and reporting. As covered by the press, the case of Shell has also involved management failings and poor handling of relationships with shareholders, the investment community, and the media.

Not all "proved reserves" reported by oil companies follow definitions of the US Securities and Exchange Commission, and not all of them are exaggerated and incorrect. SEC definitions are very restrictive but have been applied to oil and gas fields in the US. For the rest of the world, the definition of proved reserves has been more flexible and expansive and has included more oil than the SEC definition.

The key question is whether companies whose shares are traded in the US should follow the SEC definition also for their oil and gas fields outside the US. It appears that this is an uncertain area with room for different interpretations.

Some industry professionals have been critical of SEC requirements. They point out that the definitions were prepared decades ago, are unnecessarily restrictive, cause wastage of funds, and should be updated to take account of advances in exploration and production technology. It is interesting that the SEC recently accepted part of the industry arguments and allowed greater reliance on seismic information rather than confirmation only by drilling. However, this acceptance has been restricted only to the US part of the Gulf of Mexico. International companies are now pressing for its wider application in other parts of the world.

Politics and oil

A discussion of the oil market and its future must include an examination of politics—global, regional, or domestic. Politics distorts operations of the industry, the oil business, and the oil market. Nevertheless, politics has played an important role in oil in the past, it is critical in the world oil scene today, and it seems certain to continue playing such a role in the future.

Exporters' concerns

Officials of many oil-producing, oil-exporting countries remember excesses of the former oil concessionaires and their own nationalization campaigns in the early to middle of the last century. The world is now different, but memories remain.

For many decades the world oil industry was run by a limited number of major international oil companies in a kind of global oligopoly. The companies operated in different parts of the world, partly with a tacit agreement as to each other's "turf." The companies held oil concessions in many countries, and in most cases the concessions covered large parts of the country.

The influential role of those companies is well documented. The concessionaires operated almost as states within states. They were very influential in government policies and domestic politics of the countries in which they worked. They brought about changes of ministers, governments, and presidents and even initiated military coups. Some of these companies were acting almost as the extensions of the foreign and intelligence services of their home countries. The unfair terms of agreement, the one-sided relationships, and failed oil nationalization attempts in the host countries were some of the results of the closeness of the oil companies with those services.

Today, oil companies are very different from their predecessors of the first half of the last century. The governments of producing countries are also different. Moreover, many of these countries have experienced decades of running their own oil industries through national companies. Some have reestablished business relationships with the international oil companies, and others wish the companies to reenter their countries' oil and gas activities. Nevertheless, the historical background remains important because those events persist in the minds, and in some cases emotions, of many in the producing countries.

Companies' concerns

Companies today try to operate as businesses and prefer to keep away from politics. They negotiate with the producing countries and strive to reach agreements and operate under mutually beneficial relationships. They are no more wielding undue political influence as in the days of the concessions.

In fact, oil companies now complain that governments of the oil-producing countries are imposing increasingly stringent regulatory regimes and often change the terms of taxation and export rules to their disadvantage. In addition, companies complain that frequent, unforeseen changes in the countries' domestic political scenes cause yet new changes in the regulatory terms and introduce further uncertainties for their operations. Companies also have faced revolutions and wars in the past few decades. The political risks in many producing countries are said to be greater or at least as important as the technical risks.

Companies with experience in international operations recognize the inescapable political dimension of their activities. An example was insistence by the late President Haydar Aliyev of Azerbaijan that the signing of contracts with US oil companies take place in the White House in the presence of former President Bill Clinton. A more recent case is the Russian government's harsh and politically related treatment of the formerly prosperous and now bankrupt OAO Yukos.

International oil companies are generally familiar with these realities and consider them part of their global business and operating environment.

Home-country concerns

In recent years, many companies have come to face growing political risk and uncertainty in their home countries. The best example is US imposition of oil sanctions on many countries, placing numerous prospective and attractive areas outside the reach of American oil companies.

Non-American companies also face threat of third-party sanctions from the US government. The validity of extraterritorial provisions of US sanction laws has been legally challenged. Nevertheless, companies still face these threats if they decide to work in some parts of the world.

Oil and gas investments have been reduced and delayed in the countries under US sanctions. The delays in production-capacity expansion in Iraq, Libya, and to some extent Iran are examples that become more noticeable under the presently tight market. And American oil companies have lost attractive business opportunities to competitors from Europe, Asia, and other parts of the world that have participated in oil activities in sanctioned countries.

US sanctions and their effectiveness remain subject to continuing debate.

Long-term outlook

Any view of oil-industry operations decades from now must account for the major changes to the business and world that have occurred since the days of oil concessions. In general, companies and countries acknowledge their needs for one another.

Moreover, a third dimension of the global oil scene is evolving. Consolidation in the oil-field services industry has created a new species of major company. In this category are firms offering the whole spectrum of upstream operations such as field, laboratory, and office services. Their operations include work traditionally performed by oil companies, such as seismic interpretation, reservoir analyses, production planning, and even operations management.

If capital is available, producing countries can enter contracts with these service companies or establish strategic alliances with them and apply advanced technology and field practice in their oil industries. An example is the impressive performance of the oil industry in Russia in the last few years, much of it based on alliances with service companies. Growth of the services sector thus might foster alternative arrangements for the producing sector.

Supply security

A key factor in future oil supplies is that all countries that produce oil beyond their own needs are and will remain keen to sell the excess in the global market. This statement is valid for members of OPEC, producers outside the organization, and countries in which oil might be discovered in the future. Politics might cause temporary disruptions of exports in specific countries but will not end them.

Oil supplies have become geographically diversified. More importantly, major producing and exporting countries have become dependent on revenue from their oil exports. Any possible disruption would be temporary.

Obviously, a disruption of exports from a major oil producer will cause a crisis in the world oil market. However, the disruption would not be sustainable. The global oil market should not be concerned about the security of long-term supplies due to political developments.

Demand outlook

Most forecasters, such as the International Energy Agency, expect relatively high growth of world oil demand in the coming decades. This discussion does not disagree. It does, however, suggest a possible alternative: that world oil demand might grow at lower rates and might even become stagnant.

The prospect of continued high demand should warn against complacency by consuming nations. Public policies can and probably will moderate oil demand. More importantly, if the price of oil remains high, demand will naturally decline.

Similarly, producers should not become complacent about high prices and security of demand for their oil. No discussion of the long-term outlook for oil should ignore the existence of alternative energy sources, including still-abundant coal.

Supply outlook

Most forecasters expect oil supplies to be sufficient to meet projected levels of future demand. The view of this author is that oil supplies will be sufficient at least well into the next decade. Obviously, oil supplies cannot increase indefinitely, and supply constraint could, theoretically, occur. Oil is a finite resource and the warnings by more-pessimistic analysts are well justified.

The world will not, in any case, suddenly run out of oil. Various indicators would provide warnings beforehand. The dwindling of oil resources would manifest itself as a slowdown in supply growth and then a few years of a plateau rate of production. The world socioeconomic system is much more intelligent and versatile than any individual. It will deal with the inevitable reduction of oil supply, apply corrections, and adapt to the new situation long before the world physically runs out of oil.