The global market for diesel fuel is changing fundamentally as sulfur-content limits take effect in the largest consuming regions. Trade patterns are shifting, and supply strains threaten some areas.

The issues will come into sharp focus next year, when new sulfur limits on highway diesel begin taking effect in the US. While refining capacity sufficient to meet the new specifications is believed to be in place, worries linger about the potential for spot shortage arising from unresolved logistics and enforcement questions.

If problems develop, the US market will not be able to rely on Europe for supplemental diesel to the extent it did for gasoline when hurricanes shut down Gulf Coast refineries in August and September. Besides diminishing sulfur content, another major change affecting global diesel trade is Europe’s rapid growth in consumption of the fuel-a development that, for at least a few years, will make surplus gasoline available to the US.

Furthermore, Europe and the US aren’t the only regions where diesel demand is growing.

Industry concern about diesel was evident in Nov. 9 testimony by James J. Mulva, chairman and chief executive officer of ConocoPhillips, at a congressional hearing addressing gasoline supplies and prices following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita.

“Diesel supplies have proved to be more difficult to import than gasoline supplies because of the tight global diesel supply-demand balance and particularly strong demand for diesel fuel in Europe, which prevented some product from being diverted to the United States,” Mulva told a joint hearing of the House Commerce, Science & Transportation and Energy and Natural Resources Committees. “This also demonstrates the risks of biasing consumers towards one fuel over another.”

European tax policies have long favored diesel consumption and pushed European demand for the product past that for gasoline, raising prices, Mulva pointed out. US consumers feel the pressure not only with diesel fuel but also with heating oil, which differs from diesel only in sulfur content. Further tightening the US market has been the need of refiners to produce gasoline at maximum rates to meet demand.

“As the refining industry prepares to meet the congressionally mandated deadline for producing low-sulfur diesel by June 1, 2006,” Mulva warned, “you may continue to observe erratic pricing in diesel markets next year.”

Global changes

Changes in diesel trade extend well beyond the Atlantic Basin.

Rising demand and tightening specifications are worldwide developments, notes Sarah Emerson, managing director of Energy Security Analysis Inc. (ESAI), Boston. A multiple-quality diesel market is developing, she says, with demand migrating from higher to lower sulfur content and eventually to ultralow-sulfur.

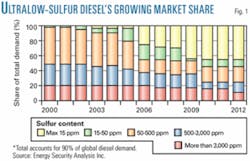

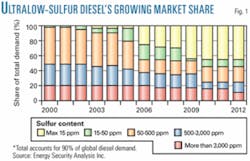

According to an ESAI projection shown in Fig. 1, ultralow-sulfur diesel will represent nearly half of the diesel sold in major markets by the end of this decade as countries around the world tighten or implement sulfur limits (Table 1).

Emerson says an ESAI analysis of every country for which data are available raises questions about the adequacy of on-specification diesel supply.

During 1995-2004, the analysis shows, global diesel demand grew by an average 550,000 b/d/year. The growth rate is likely to increase, driven by China, where diesel demand increased by 350,000 b/d in 2004 alone. Although that rate won’t last, Chinese diesel demand growth will remain strong, possibly 100,000-200,000 b/d/year, ESAI says.

If economies continue to grow in Asia and the US sustains growth in gross domestic product of at least 3%/year, global diesel demand could potentially grow by as much as 650,000 b/d/year during the next 10 years and beyond.

An ESAI analysis of refining capacity expansions indicates that, if demand growth is that high, diesel production increases worldwide will struggle to keep up, increasing by perhaps 550,000 b/d/year during the next 10 years.

While some of the prospective 100,000 b/d/year deficiency can be made up from additional refining capacity and alternatives such as gas-to-liquids and biodiesel, Emerson says, the likelihood is for “a tenuously balanced-to-tight global market over the next decade.”

‘Unusual’ prices

Even before hurricanes disrupted US supplies this year, diesel prices were indicating that something more than supply-demand stress was under way.

In a winter fuels conference in October, John Hackworth and Joanne Shore of the US Energy Information Administration pointed to “very unusual distillate prices” in the US and Europe.

Normally, US prices for distillate-including diesel and home heating oil-exceed those for gasoline for only brief periods, most often in fall and winter. But this year distillate values remained higher than gasoline until the hurricanes hit.

Relative distillate prices this year have been unusually strong outside the US, too. Heating oil prices in Europe and Asia exceeded gasoline prices through late summer.

“The provocative question is whether this highly unusual gasoline-distillate price situation in summer 2005 stems from a temporary situation or is the beginning of a more fundamental shift in the relative pricing of these primary light refined products,” Hackworth and Shore said.

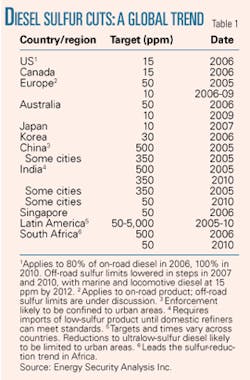

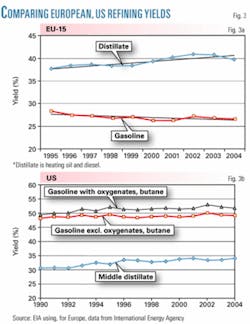

Central to this question is Europe’s rapidly growing appetite for distillate relative to gasoline use, which is falling (Fig. 2a). The product-mix shift is driven by the diesel component of distillate consumption. And diesel values are growing in comparison with heating oil as regulations lower diesel sulfur content.

The EIA analysts said the difference in Europe between prices of ultralow-sulfur diesel and heating oil averaged about 13¢/gal during the past year, while in the US, New York Harbor spot diesel prices averaged about 4¢/gal over heating oil.

Unclear is whether the European differential reflects transition issues or longer-term factors, the analysts said. Also unclear is whether the US will experience similar price differences. The US question will remain especially difficult to answer during next year’s start of the transition to ultralow-sulfur highway diesel.

US-Europe balance

While diesel’s position as the primary vehicle fuel in Europe strengthens, gasoline will remain dominant in the US, even though diesel demand will rise there, too (Fig. 2b). The regions’ contrasting diesel vs. gasoline patterns, together with refiners’ needs to slash diesel sulfur content, are crucial to future product trade and pricing.

Anticipating the growth in diesel demand, European refiners have invested heavily in capacity oriented to the production of distillate. The EIA analysts pointed out that between 1990 and 2004 hydrocracking capacity of 11 of the major refining countries of the European Union as a share of distillation capacity increased from 2% to nearly 7%. During the same period, fluid catalytic cracking-which increases gasoline yield-rose to 16% of distillation capacity in 1996 and has remained at about that level.

Distillate yields of European refiners therefore are climbing while gasoline yields gradually fall (Fig. 3a). In the US, yields of middle distillates are rising, too, but remain well behind those of gasoline (Fig. 3b).

Despite European refining adjustments, a product imbalance persists. European refiners still can’t make enough diesel to meet demand and, according to Hackworth and Shore, probably will remain behind market needs even when planned hydrocracking projects come on stream. Furthermore, they’ll continue to produce more gasoline than local markets need.

Net trade in middle distillates by the 15 countries that made up the EU before the 2004 enlargement (EU-15) increased from a small export position in 1995 to more than 500,000 b/d of imports in 2004, the EIA analysts said. Of that, 400,000 b/d was diesel and gas oil, about three fourths of it from the former Soviet Union. About 200,000 b/d was kerosine and jet fuel, more than half from the Middle East. During the same period, net gasoline exports, although varying year to year, doubled to nearly 800,000 b/d.

A problem may lurk in Europe’s distillate-gasoline imbalance. In 2004, Hackworth and Shore said, European growth in distillate imports didn’t match that of gasoline exports.

“Is that a situation that is likely to continue?” they asked. “Does it reflect growing difficulty in finding economic distillate imports? Perhaps.”

Compounding the potential supply difficulty, the analysts added, is the need not just for distillate but for diesel able to meet tightening European sulfur specifications as well. The squeeze might add to the pressure on diesel prices, which would further raise the incentive of European refiners to increase distillate yields at the expense of gasoline.

US requirements

The strength of that incentive to further tune European refineries toward distillate production will determine how long the European surplus of gasoline remains large and growing.

The surplus is of course convenient for the US; indeed, a surge of imports from Atlantic Basin suppliers helped the US market adjust to the shock of refining capacity idled by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita.

Net imports, the EIA analysts noted, accounted for about half the growth in US gasoline supply from 1990 through 2004, when they averaged 800,000 b/d. That was about twice the import level of 1990. During January-July this year, average US gasoline imports from Western Europe exceeded 400,000 b/d, more than twice their average for the same period of 2000. According to Hackworth and Shore, the growth reflects both the European gasoline surplus and the ability of European product to meet US sulfur specifications, which began taking effect in 2004.

Unlike the case with gasoline, distillate demand growth in the US has been met since 1995 largely from refinery operations-increases in both crude runs and yields. For gasoline, supply gains from refinery operations come mainly from increased crude inputs.

The contribution of imports to US distillate supply is less important than it is to gasoline supply and for distillate is greatest during sudden, extreme cold snaps. Western Europe-with less distillate than gasoline available for export-accounts for a much smaller share of US imports of distillate than it does of gasoline. In view of Europe’s diesel supply challenges, that’s not likely to change.

If the US encounters problems with diesel supply, therefore, it can’t count on substantially increased imports from Europe as it has been able to do with gasoline.

Questions in 2006

Supply difficulties are possible as the requirement begins taking effect next year for highway diesel with no more than 15 ppm sulfur. Whatever immediate problems arise, however, may have more to do with logistics-product contamination downstream of the refinery-than with refinery capability.

In an analysis last month, David Isaak of FACTS Inc., Honolulu, said regulatory complexity makes uncertain how much ultralow-sulfur diesel will enter the market next year.

Sales of diesel meeting the new standard don’t need to begin until September, he pointed out. And since his report, the Environmental Protection Agency, in response to the logistical concerns, has further relaxed the deadline by allowing retail sales of highway diesel containing as much as 22 ppm sulfur until Oct. 15. Deliveries to terminals of ultralow-sulfur product must start in May, when 80% of the production of highway diesel by most refiners must be at 15 ppm sulfur. Most refiners, in fact, will target sulfur content of 10 ppm or less to meet pipeline requirements.

The regulations exempt from the ultralow-sulfur requirement refiners that in 1999 had 1,500 or fewer employees and total distillation capacity not exceeding 155,000 b/cd. Regulations also provide for sulfur credits that can be traded among companies.

Further complicating the volume outlook is a 2-year extension on compliance with gasoline sulfur specifications for refiners in Rocky Mountain states and parts of Alaska that meet the new sulfur standard for 85% of their output of highway diesel.

All that is clear now, Isaak said, is that all road diesel must contain no more than 15 ppm sulfur at the pump by May 31, 2010.

“In the interim years, such as 2007,” he said, “perhaps only 75% of all diesel will have to meet this spec.”

Refinery adjustments

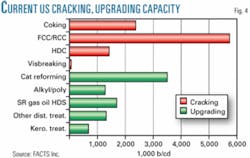

Refinery revamps undertaken in response to the new diesel-sulfur specifications have occurred mainly in straight-run gas oil hydrodesulfurization (SR gas oil HDS, Fig. 4). Units dedicated to kerosine treatment aren’t suited for deep desulfurization of gas oil, Isaak noted. The Fig.4 category for other distillate treatment involves treatment of cracked material such as FCC light-cycle oil and coker gas oil, usually not involving pressure or volume for deep desulfurization although some refiners have applied aggressive treatment in this area.

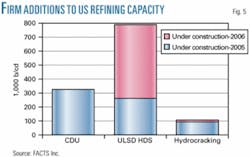

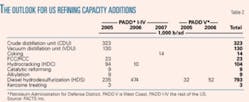

In addition to revamps, which are expensive and don’t show up in capacity data, many refiners are adding ultralow-sulfur diesel hydrodesulfurization (ULSD HDS) units. Isaak said this is the largest item in current plans for additions to US refining crude and processing capacities. Firm ULSD HDS capacity additions total nearly 800,000 b/d in 2005-06, followed by crude distillation units (CDU), slightly more than 300,000 b/d, and hydrocracking, slightly more than 100,000 b/d (Fig. 5).

Isaak said there are several other hydrocracking projects of unannounced size in the engineering or feasibility stages. And some ultralow-sulfur revamp projects have been reported without capacities. Table 2 shows the projected timing and locations of capacity additions of various types.

“There is no question that US refiners have been less eager than their European counterparts to invest in tighter specifications,” Isaak said. “Nonetheless, the volume of new diesel HDS slated to come on stream in a 2-year period is enormous.”

Uncertain, because not all projects are reported, is the extent to which revamps have made existing hydrodesulfurization capacity able to produce diesel to the new standard. Isaak said industry estimates suggest 40-45% of existing capacity has been revamped for ultralow-sulfur diesel, although not all to 15 ppm. By next year, revamps might cover more than 85% of capacity.

The biggest uncertainty about US diesel, however, Isaak said, is the extent to which refiners will produce ultralow-sulfur fuel above the 80% requirement taking full-year force in 2007.

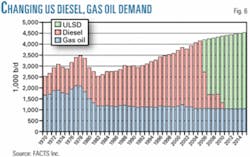

The projection in Fig. 6 assumes that all refiners move to the 80% level on the legislated schedule but don’t exceed it until required to do so in 2010. It also doesn’t assume widespread use of variances such as the gasoline-sulfur offset and small-refiner exemption. Broad use of the variances could lower ultralow-sulfur diesel supply by about 160,000 b/d.

But ultralow-sulfur diesel supply could be about 650,000 b/d higher than the projection if refiners apply the new standard faster than required by law. While some companies will do so, Isaak said, the availability of credits will encourage others to delay the needed investments.

“If the industry presses itself,” he said, the need for US imports of ultralow-sulfur diesel can be held low.

“In the longer term, however, the problem is not quality but total volume,” Isaak warned. “Diesel and jet fuel are the two products where we foresee the fastest growth in US demand. Unless the US refining industry expands substantially beyond present plans-which would require major changes in domestic policies-then demand for imports of most products will mount.”

Distillate and crude

Growth of demand for diesel of rising quality is giving the middle distillate range of petroleum products new influence in the broader oil market.

In its September-October Global Oil Report, the Centre for Global Energy Studies in London traced major changes during the past 2 years in market dynamics.

Traditionally, CGES said, oil prices have closely followed stock levels and forward cover-the days of expected consumption that can be supplied from inventory. Prices tend to rise as stocks and forward cover decline.

In the past 2 years, however, especially for crude, prices have risen despite rising inventories. CGES believes the main influences on the crude price recently have been distillate-crude value differences (crack spreads), refinery utilization, and middle distillate demand.

“The upward pull on prices from all of these is currently outweighing the downward pressure from rising crude oil stocks,” CGES said. Increasing refinery utilization, moreover, has been led by gains in product demand rather than reductions in feedstock costs.

The unexpected increase in the crude price this year, the group said, “is almost certainly related to the cost of making extra distillate.” As demand rises and refinery utilization increases, hydroskimming capacity comes on stream, reducing yields of light and middle distillates. With insufficient desulfurization capacity available to meet new product specifications, refineries must reduce the depth of the gas oil cut to meet sulfur limits, further reducing yields. And incremental crude supply tends to be high-sulfur Middle Eastern grades.

“In other words,” CGES said, “the more crude that is run through the refining system, the more difficult and expensive it becomes to produce enough middle distillate of the right quality.” At a critical level of refining capacity utilization, the cost of producing an extra barrel of distillate increases rapidly, pushing up diesel and jet fuel prices.

“Product-and predominantly middle distillate-prices will continue to sustain crude oil prices, even in the face of high crude oil stocks, so long as producers are willing to forgo extra marginal sales of crude at lower prices,” CGES said. But a reduction in the crude price sufficient to make marginal hydroskimming yields profitable “will tip the current balance between high product prices and crude.”✦