Irish Drilling—Conclusion: Analyses promote cost-effective offshore drilling

Engineering downtime analysis of all exploration wells drilled off Ireland produced recommendations to improve drilling performance off Ireland. Drilling time-depth curves for different sectors can be used as a reference for estimating budgets for summer drilling.

The first part of this series, published last week (OGJ, Dec. 5, 2005, p. 41), discussed the methodology of the engineering downtime analysis study recently commissioned by Ireland’s Petroleum Infrastructure Program, and the specifics of three of the five geographic areas encompassing Ireland’s offshore basins.

This concluding part covers the far western and southwestern basins, including the Porcupine basin, Goban Spur, and Rockall basin.

Porcupine, Goban Spur basins

These basins are in deep water off southwest Ireland, in the Atlantic Ocean. Wells have been drilled with semisubmersibles and drillships in water nearly 1,000 m deep in the Goban Spur basin.

Geologically, the deepwater regions west of Ireland tend to have a thicker Recent and Tertiary sedimentary section than elsewhere off Ireland so that wells are usually drilled to greater total depths. Potential reservoir formations are Tertiary, Cretaceous, or even Jurassic (such as the six wells drilled in the Connemara field, Porcupine basin).

Overall, there have been 37 wells drilled in the Porcupine basin, second only to the Celtic Sea (89 wells in the North Celtic; 3 Marathon Oil Co. wells in the South Celtic) in terms of total wells drilled, although activity has dropped in recent years. There has been only 1 well drilled in the Goban Spur basin, by Esso Exploration and Production UK Ltd. in 1982.

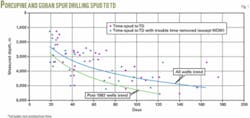

Fig. 1 shows the spud-to-TD drilling times for all wells in the Porcupine and Goban Spur basins. The “raw” time (purple diamonds) includes all flat spots (casing and BOP installation, intermediate logging, etc.), and the filtered time (triangles) depicts the data with non-productive time (NPT) during the spud-to-TD phase removed. Weather downtime is included. There is considerable data scatter, but the blue curve on the graph is a reasonable fit for NPT-free time vs. depth.

From the data review, it seemed apparent that the time-depth curves were being influenced by some very slowly drilled wells drilled in the earliest years of Porcupine basin exploration. For this reason a curve was fitted with only the wells drilled from 1982 (green, Fig. 1). These later wells were drilled over a similar range of depths to the full sample of wells.

The trouble-free spud-to-TD times were consistently quicker for the more recent wells. The green line indicating the more recent drilling performance could be used as a benchmark for planning and costing purposes, bearing in mind that, although this includes an allowance for summer weather delays, it does not include other NPT.

Fig. 2 illustrates the segregation of drilling downtime into different categories for wells in the Porcupine and Goban Spur basins. The following conclusions were drawn from an analysis of downtime information:

• Weather conditions in the Atlantic Ocean west of Ireland are severe. Operations are limited to an April-September drilling season.

• The ideal drilling unit for Goban Spur and Porcupine operations is a large semisubmersible (dynamically positioned or moored). Smaller, third-generation semisubmersibles are also capable of operating successfully in the Porcupine basin albeit with a greater risk of weather-related downtime. Average historical weather downtime for wells drilled with a semisubmersible is 2.5 days/well.

• Drilling conditions in the Goban Spur and Porcupine basins are relatively benign. There can be some moderate hole problems, often associated with overpressure, but in general, there should be no major problems in drilling vertical wells with water-based mud.

• Pore pressures in the Porcupine basin, evaluated from the wells drilled to date, have ranged from normally to significantly overpressured, approaching 15.0 ppg equivalent mud weight. The overpressure tends to build in the Cretaceous and peak in the Jurassic section and would appear to be present only when there is a thick Cretaceous section overlaying Jurassic.

• Historically, it has taken a long time to drill wells in the Goban Spur and Porcupine basins. Early wells have tended to exaggerate this perception due to the additional time required by use of dual stack systems, pin connector top hole drilling, and lack of suitable drilling bits.

• Drillers made significant improvements in drilling performance in the Porcupine basin since the first wells in 1977 and the last wells in 1997 and 2001. Improvements can be expected to continue, based on continuing advances in PDC bit design.

• Drilling performance in the highly directional Connemara field wells (Poprcupine basin) was relatively good when using nonwater-based mud (ester mud).

• Historically, the largest single source of downtime in Goban Spur and Porcupine wells has been BOP-related failures (5.9% of total operations time). This statistic has not improved over the 20 years of drilling operations in this region.

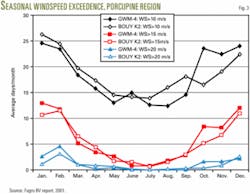

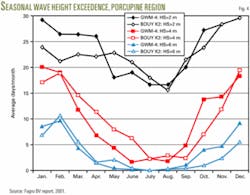

The Goban Spur and Porcupine basins are in the North Atlantic and regularly subjected to extremely severe ocean conditions. Figs. 3 and 4 illustrate the typical measured and calculated seasonal wave heights for the region.1 The data are from a regional, comprehensive climatology study that described metocean conditions west of Ireland from the southern Porcupine and Goban Spur basins to the Rockall basin in the north. Data in Figs. 3 and 4 show actual measurements at the K2 buoy situated at 51°N, 13'W, which is almost in the center of the Porcupine basin.

Rockall basin

The Rockall basin is in ultradeepwater, beyond the Erris, Slyne, and Donegal basins. Only three wells have been drilled in the Rockall basin, one by Enterprise Oil UK Ltd. in 2001 and another well plus sidetrack by Enterprise Energy Ireland Ltd., a subsidiary of Enterprise Oil, in 2002-03.

Smedvig AS set the record in 2001 for drilling in the deepest water off Ireland (1,623 m), using the West Navion drillship to drill the first Rockall basin well for Enterprise Oil.

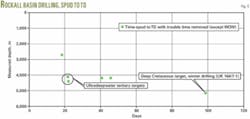

The data in Fig. 5 include the Rockall basin wells and three wells from an adjacent part of the UK sector. The spud-to-TD drilling times for the six wells, however, do not seem to show any particular trend. Progress heavily depends on formations drilled. The soft Tertiary sections are readily drillable, such as encountered on wells UK164/25-2, 5/22-1, and UK132/6-1. But drilling Cretaceous and older section can be much more time consuming. The frequent presence of volcanic dolerite sills in this area can also have a significant detrimental effect on drilling progress.

All the Irish wells and virtually all the UK wells in the Rockall basin have been drilled in the last 15 years with LWD, PDC bits, and other modern technologies capable of reducing overall well drilling times. In these water depths, there is likely to be overall improvement in operational times with the latest dual-activity rigs.

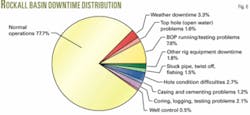

Fig. 6 illustrates a breakdown of drilling downtime, leading to the following conclusions:

• The single greatest risk of downtime in ultradeepwater conditions of the Rockall basin is BOP equipment-related failures. This finding is supported by analysis of the Porcupine basin wells.

• The availability of drilling rigs rated to drill in water depths greater than 700-800 m is very limited within Europe. It is likely that for any future Rockall basin drilling a rig would have to be mobilized from another deepwater region, such as West Africa.

• Heavy-duty, dynamically positioned rigs are likely to be the preferred choice for exploration drilling, particularly for water deeper than 1,500 m.

• Weather conditions are a major factor in overall cost of the drilling operation, although historically weather downtime has not resulted in extended downtime during summer operations.

• Winter drilling is possible with large semisubmersibles, but downtime will increase significantly and there is an increased risk of storm damage to the equipment.

• Fast drilling is possible, especially in the Tertiary sections. Cretaceous and Jurassic sections are tougher to drill, especially where volcanic sills are present.

• Overall, formations in the Rockall basin are more drillable than other areas of the Irish shelf, and there is a wide application for PDC bits. High ROP and long bit runs have been achieved on the Irish Rockall shelf wells in all formations.

• Water-based mud is a suitable drilling fluid for vertical wells. This is important for environmental and logistical reasons, which could preclude the use of oil-based mud. Hole conditions are generally relatively benign.

• Top hole operations can be carried out successfully with good planning. The preferred and most successful method of conductor installation has been to drill and cement, although jetting the conductor may become a more viable option as water depths increase.

• Within this area, there is a risk of encountering significant overpressure in the Cretaceous and Jurassic, which could result in a well control incident. Deepwater conditions can complicate well control operations and careful contingency planning is required to ensure any kick can be dealt with safely.

Ocean currents can be critical in deepwater drilling due to loads imposed on the drilling riser. Enterprise Energy Ireland Ltd. carried out a current monitoring program before drilling in the Rockall basin. Occasionally, moderately strong current eddies were detected over the year of data collection, but overall the currents were less severe than has been observed in some of the more northern UK deepwater drilling and there was no issue with riser design.

Irish drilling downtime

In summary, the most significant sources of downtime in Irish offshore drilling operations are:

• Weather downtime, significant in all areas. Historically, most weather downtime is in Celtic Sea operations. This is because winter drilling was attempted in the early days.

The statistics are not helped by a number of early wells drilled with small drillships, which were inappropriate for the sea conditions prevailing. Later wells were less prone to weather delay, particularly after operations became predominantly seasonal. Weather is a less significant source of downtime in deepwater Atlantic operations because operators adhere to a strict summer drilling and use heavy-duty rigs, less susceptible to weather delays.

• BOP problems, are very significant in deep water west of Ireland operations due to the marginal conditions and harsh environment. Operators may have to use rigs at the limits of their capability, due to limited rig availability. The lack of improvement over time is of most concern.

• Top hole and open water problems. Respuds have been quite frequent, particularly in early Porcupine wells. Central Irish Sea Blocks 41 and 42 have particularly troublesome formations with additional difficulties created by strong currents.

In the Celtic Sea, drilling the top hole was troublesome in some areas. Drilling multiple wells allowed operators to implement lessons learned to reduce downtime. In the Corrib area especially, operations have benefited from lessons learned drilling top hole.

Early wells often encountered problems during well abandonment but this has improved. Deepwater wells have fewer problems, possibly due to more thorough planning.

• Stuck pipe and drillstring problems, account for 3-4% of downtime in the Central Irish Sea, Celtic Sea, and Porcupine areas. Hard drilling in shallow formations in the Celtic Sea and Central Irish Sea can be an issue. The use of underreamers on older wells caused problems.

Improved pipe inspection practices have clearly reduced the number of string failures. There are fewer stuck pipe and drillstring failures on the more recently drilled Slyne and Rockall basin wells.

Other factors that increase well time and cost include: slow drilling in some formations with poor bit durability and excessive evaluation, particularly in early exploration wells prior to LWD availability when drillers made frequent intermediate logging runs.

Positive factors

Among the positive aspects to drilling off Ireland may be added the recent very fast drilling and completion of production wells with horizontal trees in the Celtic Sea. Furthermore, there is a choice of good port and airport facilities in suitable geographical locations to service all drilling areas.

The industrial problems seen in the past are no longer an issue. Ireland is not a particularly “remote” operation. Depending on the length of operation, it is feasible to set up a forward base in Ireland for Irish shelf operations without excessive cost compared to a North Sea operation.

With good planning, an operator can move most drilling equipment and supplies to Ireland on the drilling rig and supply boats, and there are adequate road and ferry links for additional equipment transport from Aberdeen.

Acknowledgments

The Irish Shelf Petroleum Studies Group (ISPSG) of the Petroleum Infrastructure Program (PIP) commissioned and funded the drilling downtime project. ISPSG and the Petroleum Affairs Division of the Department of Communications, Marine and Natural Resources, Dublin, granted permission to publish this article. ✦

Reference

1. “West Of Ireland Descriptive Regional Climatology Study,” prepared by Fugro BV on behalf of the Petroleum Infrastructure Program, 2001.

Bibliography

Calverley, M., Stephens, R., and Wade, I., “West of Ireland Descriptive Regional Climatology,” Internal Report of the Irish Shelf Petroleum Studies Group, 2000.

Ross, G., and Ross, G., “Engineering Downtime Analysis and Cost Effective Drilling.” Internal Report of the Irish Shelf Petroleum Studies Group, 2004.