Safety, security, legislation affect approvals

US IMPORT TERMINALS-1

The planned expansion of the number of LNG import terminals in the US brings myriad safety, security, governmental, and regulatory concerns. It also raises a host of issues dealing with quality and interchangeability of any natural gas imported through these terminals.

Three of the four current US terminals are undergoing expansion, a new offshore terminal has been completed, as of September 2005 10 more terminals have received construction permits, and more than 30 other projects have been proposed.

On Aug. 8, 2005, US President George W. Bush signed into law the Domenici-Barton Energy Policy Act of 2005 which contains provisions addressing some of these issues. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) and the US Coast Guard (USCG) are responsible for the permitting of the new terminals, with FERC having jurisdiction over onshore facilities and the USCG having jurisdiction over offshore facilities.

This first article of a two-part series discusses issues facing FERC in approving applications for new LNG import terminals, particularly safety and security issues. It also addresses the effect of the new energy legislation on LNG terminal development, with particular attention paid to remaining state and local authority in light of FERC’s mandate.

Part 2 will detail the gas quality and interchangeability issues faced by the US as a consequence of expanded use of LNG.

Safety, security

The single most important issue facing US regulators in permitting new LNG import terminals is how to protect local citizens against the consequences of a release of LNG. Despite the excellent safety record of LNG facility operators, both onshore and in transit, public concerns remain intense.

Against this backdrop, FERC and the USCG have developed tools to help understand the consequences of an LNG spill and to develop appropriate safety and security measures at both existing and newly certificated LNG import terminals.

Issues regarding LNG security arose immediately after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, when the USCG suspended LNG shipments through Boston Harbor bound for Distrigas of Massachusetts LLC’s terminal at Everett, Mass. Shortly thereafter, concerns about the potential for a terrorist attack were raised during the reactivation of Dominion Cove Point LNG LP’s terminal at Cove Point, Md., particularly given its proximity to Constellation Energy’s Calvert Cliffs nuclear power plant, only 3.5 miles away.

In both instances, FERC consulted with the Coast Guard, other federal agencies, and local officials to ensure that the measures being taken were sufficient to guard against acts of terrorism.

As interest in LNG development grew, it became apparent that a scientific consensus regarding the consequences of LNG spills had yet to emerge. A pair of studies was commissioned to settle the debate and establish a baseline scientific approach to consequence assessment, subject to new developments.

In December 2003, FERC commissioned ABSG Consulting Inc. to identify appropriate consequence analysis methods for estimating flammable vapor and thermal radiation hazard distances for potential releases from LNG vessels In May 2004, ABSG issued its report, recommending analysis methods for the effects of incidents involving large LNG releases on water, including vapor cloud formation, thermal radiation in the case of a pool fire or ignition of the vapor cloud, and the effect on nearby population and structures.1

At about the same time, the US Department of Energy (DOE) commissioned the Sandia National Laboratories to conduct a study of the potential for breaching an LNG tanker both accidentally and intentionally, as well as the potential size and range of hazards involved in the resulting spill of LNG. The DOE also sought guidance for applying a risk-based approach to the analysis and management of the threats, hazards, and consequences of an LNG spill over water.

In December 2004, Sandia released its study, concluding that the risks from accidental events such as collisions and groundings were small and manageable.2 While the Sandia report concluded that the risks from intentional events such as acts of terrorism could be severe, it stated that multiple techniques exist to enhance LNG spill safety and security management and reduce the potential for a large LNG spill due to intentional threats.

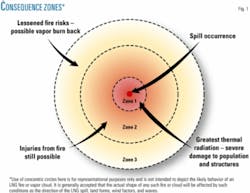

The Sandia report examined the impact of an LNG pool spill in three concentric zones. Fig. 1 shows that in the first zone, immediately around the point of the spill, the greatest impact on public safety and property is from the fire itself. In the second zone, farther from the point of the spill, there may be significant effects due to the thermal radiation caused by the fire, but these are reduced. In Zone 3, public health and safety effects are low, but the potential remains for a vapor cloud to spread and ignite.

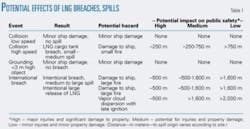

Table 1 provides approximate distances of the consequence zones for certain kinds of LNG spills. Of course, these distances would vary depending on the circumstances and characteristics of a given spill.

The report recommended that consequence-based hazard zones be developed and applied on a site-specific basis for each area along an LNG vessel’s route to determine appropriate mitigation measures to reduce the potential impact on public safety and property.

While these studies were being conducted an explosion at Sonatrach’s Skikda, Algeria, LNG liquefaction facility in January 2004 presented FERC with an additional learning experience, albeit a tragic one. FERC sent a team of engineers to review the damaged facilities and to help determine the cause of the explosion. The findings indicated that cold hydrocarbons had leaked and been fed to a high-pressure steam boiler by the combustion air fan, causing an explosion inside the boiler fire box and resulting in a larger explosion of hydrocarbon vapors in the immediate vicinity.

With this understanding, FERC inspected terminals in the US to determine whether a similar event could occur, focusing on the proximity of combustion or ventilation air-intake equipment to possible hydrocarbon releases. FERC now requires all new LNG terminal developers to conduct a detailed design review that identifies all combustion-ventilation air-intake equipment and the distances to any possible hydrocarbon release points.

More recently, the USGC issued a circular (NVIC 05-05) providing guidance on assessing the suitability and security of a waterway for LNG marine traffic.3 The NVIC requires an LNG import terminal developer to conduct a detailed, risk-based assessment of the navigational and port-security issues associated with use of the waterway for LNG vessel traffic.

In particular, the NVIC requires the developer to use the Sandia hazard zones to determine the primary areas of concern along the route. The NVIC also requires the developer to conduct both safety and security risk assessments and not only develop strategies for managing the identified risks, but also identify the resources needed to implement those strategies.

FERC has incorporated this guidance in its review of new terminal applications, requiring terminal developers to conduct waterway suitability assessments in accordance with NVIC 05-05. The results of this waterway suitability assessment form the basis of a vessel-transit security plan that must be reviewed and approved by the Coast Guard and incorporated into FERC’s approval process.

The new energy legislation also includes provisions for safety and security of LNG terminals. The legislation directs FERC to include as part of its approval process a requirement that terminal operators develop an emergency-response plan in cooperation with the Coast Guard and state and local agencies.4 Further, the legislation requires FERC to coordinate with the US Department of Defense regarding LNG import terminals that may affect active military installations.5

State, local acceptance

In approving new import facilities, FERC conducts a comprehensive environmental review in accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).6 As part of that process, FERC seeks input from state and local governmental agencies on such issues as zoning and land-use planning, historic preservation, endangered species, and other environmental issues. FERC’s process, however, is not all-encompassing. States still have direct review authority of certain aspects of the approval of new LNG import facilities.

For example, the US Congress enacted the Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA) to preserve, protect, and develop the resources of the nation’s coastal zones.7 Under CZMA, states are to develop management plans that, among other things, define the boundaries of the coastal zone, prioritize uses of particular areas, and in particular establish a planning process for energy facilities likely to be in or have a significant effect upon the coastal zone.8

Each LNG developer must certify that its project complies with the applicable state’s approved coastal management program and that such development will be conducted in a manner consistent with the program.9 FERC may not grant final approval to the LNG project until the state has either concurred with the certification, the state’s concurrence is waived by its failure to act within 6 months, or the US Secretary of Commerce overrules the state and determines that the project is consistent with the goals of the CZMA or is otherwise necessary in the interest of national security.

Similarly, under the Clean Water Act (CWA),10 states in cooperation with the Environmental Protection Agency are empowered to develop surface water quality standards to “restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation’s waters.”11 All federally licensed projects which may result in the discharge of pollutants into navigable waters are required, among other things, to be certified as compliant with the applicable state’s water quality standards.12 As with the CZMA, FERC may not grant final approval of an LNG project until the water-quality certificate has been obtained from the authorizing state agency or is waived by its failure to act in a timely manner.

States, therefore, can exert considerable influence over the development of LNG facilities even outside the FERC siting process. While the new energy legislation strengthens FERC’s role in the siting of new LNG import facilities by expressly granting FERC exclusive jurisdiction over the siting, construction, expansion, or operation of an LNG import terminal,13 it does not affect the substantive rights of states under the CZMA and CWA.14

The act empowers FERC to establish and enforce a schedule for all authorizations required for an LNG terminal and provides streamlined judicial review procedures to ensure compliance.15 The legislation, however, exempts CZMA reviews from these new requirements by directing FERC to respect the timelines established in the CZMA regulations and leaving intact the CZMA appeal process. As a result, states continue to have a significant role in the LNG approval process.

Further, the new legislation gives states a level of involvement regarding safety and security that they previously did not have. The legislation allows states to furnish advisory reports on local safety considerations to FERC during the terminal siting process.16 It also grants states authority to conduct safety inspections that conform to federal regulations and guidelines and to inform FERC of any safety violations.17

Hackberry scope

Under FERC’s Hackberry policy, a terminal developer can provide LNG terminaling service at rates, terms, and conditions mutually agreed to by the parties.18 In other words, FERC does not impose open-access conditions on the service and does not require provision of service under a FERC-approved tariff.

FERC likened the import terminal to a production facility whose costs must be recovered solely through deregulated sales in a competitive commodity market. Since the risk of cost recovery will be borne by the developer, “there is no regulatory need to require a tariff and rate schedule as a condition of approving the LNG terminal....”19

FERC concluded that its primary concern in certificating LNG import facilities was protection of the wholesale natural gas marketplace in the US. To that end, FERC indicated that it would use its authority under the Natural Gas Act to address complaints of undue discrimination or other anti-competitive behavior.

While there was some initial concern regarding how far FERC’s light-handed regulatory approach could be taken, the new legislation eliminates much of that uncertainty by expressly codifying FERC’s Hackberry policy.20 FERC is now prohibited from requiring an LNG developer to offer open-access service or to file tariffs or contracts governing the rates or terms and conditions of service.

The legislation establishes a sunset provision which allows FERC to change its policy after Jan. 1, 2015. Moreover, the legislation similarly prohibits FERC from requiring open-access and tariff requirements for expansions of existing terminals, provided that the expansion is not subsidized by existing shippers or results in degradation of service to or undue discrimination against existing shippers.21

References

1. ABSG Consulting Inc., “Consequence Assessment Methods for Incidents Involving Releases from Liquefied Natural Gas Carriers,” (2004) at iii.

2. Sandia National Laboratories, “Guidance on Risk Analysis and Safety Implications of a Large Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) Spill Over Water,” Rep. No. SAND2004-6258, Dec. 21, 2004.

3. “Navigation and Vessel Inspection Circular-Guidance on Assessing the Suitability of a Waterway for Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) Marine Traffic,” NVIC 05-05, issued June 14, 2005.

4. Domenici-Barton Energy Policy Act of 2005, Sec. 311(d).

5. Ibid., Sec. 311(c).

6. National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, 42 US Code, Sec. 4321, et seq.

7. Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, Sec. 303, 16 US Code, Sec. 1452 (1994).

8. Ibid., Sec. 306(d), 16 US Code, Sec. 1455(d).

9. Ibid., Sec. 307(c)(3)(A), 16 US Code, Sec. 1456 (c)(3)(A).

10. Federal Water Pollution Control Act, Sec. 101 et seq., 33 US Code, Sec. 1251 et seq. (1994).

11. Ibid., Sec. 101(a) and (b), 33 US Code, Sec. 1251(a) and (b).

12. Ibid., Sec. 401(a)(1), 33 US Code, Sec. 1341(a)(1).

13. Domenici-Barton Energy Policy Act of 2005, Sec. 311(a).

14. Ibid., Sec. 311(c).

15. Ibid., Sec. 313.

16. Ibid., Sec. 311(d).

17. Ibid.

18. “Hackberry LNG Terminal, LLC,” 101 FERC 61, p. 294 (2002).

19. Ibid., p. 23.

20. Domenici-Barton Energy Policy Act of 2005, Sec. 311(c).

21. Ibid., Sec. 311(e).

Based on presentation to the Gastech 2005 Conference, Bilbao, Spain, Mar. 14-17, 2005.

The author

Andrew K. Soto ([email protected]) is counsel at Sutherland Asbill & Brennan LLP, focusing on regulatory litigation, energy policy matters, and the regulatory aspects of commercial transactions in power, natural gas, and oil. Immediately before joining the firm he served as senior legal advisor to FERC Chairman Pat Wood III. Before joining the chairman’s staff, he represented FERC in appellate litigation before US Courts of Appeals in all areas of commission regulation. While in private practice he represented utilities, marketers, and industrial customers in proceedings before FERC and other regulatory agencies and in federal courts. Soto holds a BA from Franklin & Marshall College (1984) in Lancaster, Pa., and a JD from Villanova University School of Law (1987) in Villanova, Pa.