Higher natural gas demand has China looking worldwide

China’s natural gas industry has been developing rapidly since the late 1990s, but the pace of development has been particularly fast in recent years as overall energy supply in China has tightened.

Construction of natural gas pipelines has been a high priority in China, spurred by high demand for electric power and energy in general. And within the past year, more LNG terminal projects for imports have been approved by the government.

This article updates China’s major natural gas pipeline projects and the progress of various LNG import terminals. Also discussed are major challenges facing the country as a result of a significantly higher share of natural gas in China’s total primary energy consumption.

Natural gas demand, supply

China’s current natural gas supply comes entirely from domestic production. Between 1990 and 2004, the average annual growth rate (AAGR) of China’s natural gas consumption was 6.6%. That is faster than the growth of primary commercial energy consumption as a whole. As a result, the share of natural gas in primary commercial energy consumption rose to an estimated 2.8% in 2004 from 2.3% in 1990.

As the sole source of current natural gas consumption, China’s domestic output reached nearly 4 bscfd in 2004, up nearly 19% from 2003’s production of 3.3 bscfd. The overall growth of gas production since the mid-1990s averaged 9.5%/year between 1995 and 2004.

China’s future natural gas-consumption growth will come from three sources: higher domestic gas production, emerging LNG imports starting in 2006, and emerging imports of pipelined gas with earliest possible starting point between 2010 and 2015.

As far as domestic natural gas is concerned, our base-case projections show that production will rise to 6.8 bscfd in 2010 and 9.0 bscfd in 2015 (Fig. 1), providing important support to the projected higher natural gas use in China.

Over the next 10 years and beyond, China’s gas consumption will grow at robust rates, led by the power sector. Between 2004 and 2015, the use of gas for power in China will have an AAGR of 27.9%, under our base-case scenario, raising its share to 37% of total gas use in 2015 from less than 11% in 2004 (Fig. 2). Following the growth of gas use for power, the residential and commercial use of natural gas will also grow strongly during the period.

Natural gas use in the chemical sector and other industrial sectors will continue to increase, but their respective growth rates will be lower than in the power and residential sectors. For natural gas as a whole, consumption will grow by 14.2%/year on average between 2004 and 2015, according to our base-case scenario.

If the cost of LNG continues to rise and overall supply of natural gas becomes tighter, China’s natural gas consumption may grow at a much slower rate. Under our low-case scenario, the average growth rate of natural gas consumption is likely to be less than 10%/year between 2004 and 2015.

LNG terminals

Currently, China has two LNG terminals scheduled to be built, one for Guangdong LNG (GDLNG) with an ultimate contractual volume of up to 3.85 million tonnes/year (tpy) and one for Fujian LNG (FJLNG) with 2.6 million tpy. The GDLNG terminal is under construction and will be completed in mid-2006. Construction for the FJLNG terminal has just started, with completion targeted for 2008.

By 2010, the GDLNG receiving capacity likely will increase to 10 million tpy, while the FJLNG might be expanded to 5 million tpy sometime after 2010 if new demand arises for gas in Fujian or for trucking LNG to neighboring provinces.

After a series of international bidding rounds, Northwest Shelf Australian LNG (NWS ALNG) won the bid to supply GDLNG. LNG will come from the Northwest Shelf Trains 4 and 5. The sales and purchase agreement (SPA) was signed between CNOOC Ltd. and ALNG in October 2002. By 2010, the GDLNG receiving capacity is planned to increase by 6 million tpy; however, no supply source as yet has been identified.

CNOOC and BP PLC signed the FJLNG SPA contract in September 2002. The source of supply is BP’s Tangguh gas project in Indonesia. CNOOC plans to supply gas to inland areas using LNG trucks.

In addition to GDLNG and FJLNG, CNOOC and other Chinese state oil companies-PetroChina and Sinopec-have proposed a number of new projects for the next 10 years. We do not believe all of these projects will occur any time soon, but a fast expansion of China’s LNG imports appears to be certain.

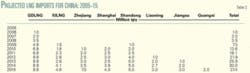

Table 1 shows a list of LNG terminals that are planned and proposed.

• GDLNG Phase II. Capacity of the GDLNG terminal is set to expand by another 6 million tpy, and the expansion is likely to be completed by 2010. Although the expansion is not yet officially approved, that is assumed to be easy.

• FJLNG expansion. Despite the fact that gas demand in Fujian province is smaller than in Guangdong, the FJLNG is still likely to be expanded to 5 million tpy after 2010. The expansion is not approved as yet.

• Shandong LNG terminal. The Chinese government has approved the 3-million tpy project at a site near Qingdao. Sinopec is involved, and the completion date can be as early as 2009. Further expansion to 5 million tpy is likely but an expansion to 10 million tpy, often discussed, will take many years to be economically justified.

• Zhejiang LNG terminal. The likely start-up date is 2010, with a beginning capacity of 4 million tpy. The project proposal has been approved by the Chinese government nominally at 3 million tpy. CNOOC and the Zhejiang government are involved. The receiving capacity may eventually be expanded to 10 million tpy.

• Shanghai LNG terminal. The start-up date may be as early as 2010, with an initial capacity likely at 4 million tpy. The Chinese government has approved the project proposal, and the investors are CNOOC and local companies. Future expansion to 10 million tpy is possible.

• Jiangsu LNG terminal. PetroChina and CNOOC are both considering building LNG terminals in this province, but PetroChina appears to be somewhat ahead. No formal government approval has been received; however, it is likely that a 3-million tpy terminal could be built as early as 2010 with possible future expansion.

• Liaoning Dalian LNG terminal. PetroChina plans to build a 3-million tpy LNG terminal at Dalian, while CNOOC is targeting Yingkou for another 3-million tpy terminal. No government approval has been received as yet, but approval is expected. Eventually, up to 10 million tpy of LNG receiving capacity may be built in Liaoning.

• Guangdong Zhuhai LNG terminal. CNOOC is considering building the second LNG terminal in Guangdong at Zhuhai. The project is not as yet approved.

• Guangxi LNG terminal. In the Beibu Gulf, CNOOC is interested in building an LNG terminal at Beihai, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. Also, PetroChina has recently reached a tentative agreement with the local government to build an LNG terminal in the autonomous region. The project is not yet approved.

Under our base-case scenario, China may start importing LNG in 2006 (around 1 million tpy). The imports are forecast to increase to 13.6 million tpy in 2010 and 37.4 million tpy in 2015 (Table 2).

It is possible that China will become the second largest LNG importer in Asia after Japan by 2015. However, there appears to be a large gap between the planned LNG-receiving capacity and the projected LNG imports, indicating that the utilization rate of the LNG terminals may be low. This is one of the great challenges facing China in its future LNG terminal construction.

Natural gas pipelines

China currently has no import pipelines.

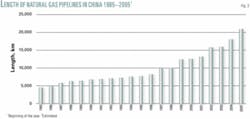

Domestic pipeline capacity is also limited but the country has accelerated the construction of new gas pipelines since the mid-1990s. In fact, China has built more pipelines since the middle of the 1990s than it did during the previous 4 decades combined (Fig. 3), and expanded urban distribution networks.

The newly built natural gas pipelines include the 4,000 km West-East gas pipeline. Others are mainly in western, northwestern, and northern China, plus a few offshore pipelines. China’s major gas pipelines are in the following areas:

• Sichuan and Chongqing. These areas are where the traditional nonassociated natural gas producing fields are located, with a fairly well-developed gas pipeline network.

• Northeast China. Associated gas is produced with some pipelines to nearby cities and towns.

• West China (Tarim basin). Some new natural gas pipelines were built in the 1990s in the Tarim basin. The West-East gas pipeline starts here as well.

• Northwest China (Ordos basin).

1. Ordos (Jingbian)-Beijing pipeline: China’s first long-distance onshore gas pipeline. It was completed in September 1997 with a total length of 919 km. Second-phase expansion was completed in November 1999 and the third phase in November 2000. Currently, the flowing capacity is 364 MMscfd.

2. Jingbian-Xi’an Pipeline: This is another onshore long-distance pipeline built in the late 1990s, which starts from Jingbian and ends at Xi’an, the provincial capital of Shaanxi Province. The pipeline was completed in June 1997 with an initial capacity of 77 MMscfd.

• North China. New natural gas pipelines were built after the completion of the Jingbian-Beijing pipeline around the Shengli, Dagang, and Zhongyuan oil and gas fields.

• East China Sea. The Pinghu gas field started supplying gas to Shanghai in April 1999 through a 400-km pipeline. Before October 2003, throughput was 42 MMscfd. After the expansion was completed on Oct. 16, 2003, the rate increased to 64 MMscfd. Further expansion should be completed this year, increasing the flow rate to 71 MMscfd.

• West-East Gas Pipelines. The original plan was to have a joint venture with the following partners: PetroChina (50%), Sinopec (5%), Royal Dutch/Shell Group (15%), ExxonMobil Corp. (15%), and OAO Gazprom (15%). Now PetroChina owns 100% of the pipeline after all other partners withdrew in 2004.

The pipeline runs from Tarim basin to Ordos, then to Shanghai. The pipeline’s length from Tarim to Ordos is 2,500 km, completed in early September 2004. Ordos to Shanghai is 1,500 km and was completed in October 2003. The flow rate was around 126 MMscfd in 2004. The majority of the gas came from the Ordos basin. The Ordos gas stopped flowing into the pipelines on Dec. 1, 2004. As such, current and future gas supply will come exclusively from the Tarim basin.

Commercial supply of the pipeline started on Dec. 30, 2004. The flow rate of the pipeline will likely reach 387 MMscfd in 2005 and 966 MMscfd in 2006. Final flow rate is likely to reach around 1.2 bscfd by 2007. PetroChina is considering increasing the capacity to 1.8 bscfd by adding more compressor stations along the 4,000-km trunkline.

Currently, the gas from the West-East pipeline is used mainly in the residential sector, which accounts for around 80% of the total. The remaining 20% is used for industry. Gas-fired power plants are being built but none of them are ready yet. Overall, natural gas is still facing the challenge from coal for power generation. Electric power generation, however, may eventually consume up to 40% of total West-East pipeline gas when 5,400 Mw of gas-fired power plants are completed in four provinces (Henan, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Shanghai) as planned.

Pipeline expansion

China’s major domestic pipeline expansion projects include:

• Second Ordos-to-Beijing line. This pipeline will be completed by October 2005, but PetroChina is working to finish it earlier. Pipeline distance to Beijing is a little longer than the first Ordos-Beijing pipeline but the route is different; the final flow rate is expected to be 1.2 bscfd, which may be reached after 2008. The gas will be delivered to Beijing and four other provinces.

PetroChina has started building a 900-km bridge pipeline from Beijing to Shandong Province. This will join with the West-East pipeline and create a national grid. The speculation is that the second Ordos pipeline is being built larger than needed to account for possible seasonality and increase in demand. That will help improve Beijing’s air quality before the 2008 Olympics. There are serious concerns, however, that Ordos may not have enough reserves to support the needed volume for the pipeline.

• East China Sea Xihu Gas Field Consortium. This is a joint venture between Sinopec (50%) and CNOOC (50%) after Unocal Inc. and Shell withdrew in 2004. The project covers two development and three exploration blocks. One development block, Chunxiao, will be on stream in 2005 and has caused tension between China and Japan over sea boundaries-flow rate reaching 242 MMscfd in 2 years through a proposed 350-km pipeline to Ningbo in Zhejiang Province.

Flow rate could rise to 387 MMscfd when another development block, Tianwaitian, becomes operational. By then nearly 484 MMscfd of gas will be supplied to the Lower Yangtze region, nearly half of the West-East Pipeline volume.

• Second West-East Pipeline. PetroChina is now mulling the possibility of building the second line, which may have a capacity of 2.5 bscfd. This will be a huge long-term goal, and the upstream supply is highly uncertain. Other than LNG imports, it is possible for China also to import natural gas from Russia by 2015 and Central Asia by 2020.

The most likely project is the proposed gas pipeline connecting the Kovykta gas field in Russia, near the city of Irkutsk, to northeast China (with a possible extension to Beijing) and then to South Korea. The total length would be 4,800 km, including South Korea, and would cost $17-18 billion. The design capacity is 2 bcfd with a possibility of 3 bcfd.

The original plan, which is unlikely to be developed, is for the pipeline to be completed by 2008. The plan calls for 1.2 bcfd going mainly to northeast China and 1 bcfd going to South Korea initially.

The flow rate to China will go up to 2 bcfd later, and about 500 MMcfd will go to Beijing. Given disagreements between China and Russia over prices and other issues, however, the pipeline is unlikely to be built before 2010. At the moment, there has been zero progress and there are no active discussions.

One possibility is for Gazprom to buy into BP-TNK and be the official promoter of the pipeline. But even these discussions are at a standstill. Imports of natural gas from Central Asia and Russia’s West Siberia will be possible only in the distant future, although since late 2004 China has stepped up efforts to study the possibility of importing gas from Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan.

Supply, pricing, other issues

Rising domestic gas production and future gas imports are important for China’s ambitious plans to double the natural gas share of primary commercial energy consumption in 10 years. China’s rush to produce more gas domestically and build new LNG terminals may put the country on track to reach that target. The availability of natural gas, however, is another challenge.

On the domestic front, although China’s natural gas resources may be huge, proven reserves continue to lag. To support the second Ordos-Beijing pipeline, which is under construction, and the second West-East pipeline, which is in the early stages of planning, proven gas reserves in the Ordos and Tarim basins are being stretched, requiring billions of dollars of new investment.

The challenge to find additional proven reserves for other pipeline projects within a reasonably short time, is even larger.

If all planned LNG terminals are built, China will have around 27 million tpy of LNG-receiving capacity by 2010 and 57 million tpy in 2015. If all of these facilities are utilized, imported LNG will account for well over half of China’s overall gas consumption by 2015.

In reality, however, as the regional and global LNG market is moving toward a seller’s market with scarcer resources, it is highly unlikely China will find all needed LNG at reasonable prices to fill up the receiving capacity. Therefore, our base-case projections show that China will import 13.6 million tpy of LNG in 2010 and 37.4 million tpy in 2015, accounting for 51% and 66%, respectively, of the total planned receiving capacity.

Another big challenge facing China is pricing. The fundamental problem with natural gas is the high cost of natural gas supply (domestic production, particularly those from the new fields through long-distance pipelines) and price consciousness of the users, particularly the electric power utilities.

For instance, the government’s set price for the existing Ordos-to-Beijing pipeline is $4.40/MMbtu at the city gate. Because PetroChina had trouble selling at this price, the actual price has been $3.70/MMbtu. None of the gas is used for power generation. For the West-East pipelines, the government guidance price is $4.20/MMbtu at the city gate, but there is a big problem selling to power companies at these prices.

Many provinces have lowered the price to potential electric power utilities to $3.60/MMbtu. At present, the break-even price for natural gas to compete with coal is less than $3.30/MMbtu. However, $3.60/MMbtu may still be acceptable.

The cost of future gas supply-either by LNG or via the proposed second West-East gas pipeline-is likely to be much higher with the selling price rising dramatically. That will present a huge challenge to the power users of natural gas. Without strong use of natural gas in the electric power sector, overall natural gas consumption may be constrained.

The Chinese government’s target to double the share of natural gas in total primary commercial energy production in 10 years and to increase it further beyond 2015 is ambitious. It requires not only continuous growth of domestic gas output at relatively high rates, but also sufficient LNG and pipeline gas imports.

It is a not a mission impossible to accomplish, but the Chinese government and its state oil companies must overcome serious hurdles to make it happen. To convert natural gas resources to proven reserves and to build more long-distance gas pipelines require huge investment.

Regional and global LNG markets are also becoming tighter. Both developments mean that the cost of future gas supply is likely to become substantially higher, creating huge challenges for China to create and build a sustainable natural gas market for all sectors of the economy, particularly the power sector.

One final note of warning regarding China: Building terminals does not guarantee gas imports. If the price of gas rises to say $6-8/MMbtu, as we argue in one of our reports, the demand for gas can slow significantly because only a few small segments of the market can afford to pay the higher prices.

The price factor and its impact on demand should not be forgotten in the excitement of the growth potential for natural gas in China. ✦

The authors

Kang Wu ([email protected]) is a fellow at the East-West Center, Honolulu. He conducts research on energy economic links, energy security, the environmental impact of transportation fuel use, and energy and economic policies in China and the Asia-Pacific region, with a particular emphasis on oil and gas. Wu holds a BA (1985) in international economics from Peking University and an MA.(1987) and PhD (1991) in economics from the University of Hawaii, Manoa.

Fereidun Fesharaki is president and founder of FACTS Inc., Honolulu. He is also a senior fellow at the East-West Center, Honolulu. He is the author or editor of 23 books and monographs and numerous technical papers on energy issues. His work focuses on downstream oil markets, OPEC policies, and Asia-Pacific oil and gas markets. Fesharaki received his PhD in economics from the University of Surrey, England.