Comment: The search for reasonable certainty in reserves disclosures

The system for disclosing proved oil and gas reserves needs to undergo significant modernization, which is overdue. The impetus for change is not limited to the industry itself, which is frustrated by the increasing gap between a system created in the late 1970s and the realities of the oil and gas industry in the 21st Century. Investors, who are supposed to be the “clients” of the system, complain that the information provided to them is not a good guide to future prospects of the companies. And there are indications that regulators themselves are coming to recognize that modernization needs to find a place on their overburdened calendars if the concept of proved reserves is to retain its credibility.

In preparing our new report, In Search of Reasonable Certainty: Oil and Gas Reserves Disclosure, we brought together in a series of workshops more than 120 representatives from oil and gas companies, accounting firms, law firms, reservoir consultants, professional associations, and academia as well as policymakers and some 50 investor representatives. There was wide consensus across the workshops about the agenda for change. Those workshops, combined with our own research, highlighted the key issues facing the reserves disclosures system today and laid out the foundations for a constructive dialogue with regulators.

It is widely acknowledged that the current regime-what we have described as the “1978 System”-is at odds with the accelerating pace of change in terms of technology, geography, markets, and the character of projects in the 21st Century. The present system does not properly inform investors about companies’ true value and prospects. Nor does it provide for accurate comparability among companies. It is not aligned with company strategies and how they invest.

Company difficulties

Companies themselves are becoming more explicit in conveying the limitations of the current system.

For example, in BP PLC’s fourth quarter 2004 results presentation, Feb. 8, the company reported that its combined proved reserves replacement ratio on a US generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP)/Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) basis was 89%, compared with 110% on a UK GAAP/statement of recommended practice basis:

“The SEC requires reserves to be estimated based on yearend prices-around $30 in 2003 and around $40 at yearend 2004. This introduces volatility into the reserves calculation, particularly for reserves booked under production-sharing contracts.”

And Questar Corp.’s news release, Mar. 8, reporting its yearend 2004 reserves along with estimates quantifying net probable and possible reserves and petroleum resource potential, came with this caveat:

“Questar is providing these estimates to help investors better understand the future potential on Questar E&P’s leaseholds beyond that reflected by currently booked proved reserves. Investors should note, however, that the company cannot include information about unproved reserves and resource potential in financial statements and notes filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission.”

ExxonMobil Corp.’s 2004 Financial & Operating Review filed with the SEC in an 8-K on Mar. 17 described the implications of its first-ever use of yearend prices to estimate its proved reserves:

“The use of prices from a single date is not relevant to the investment decisions made by the corporation, and annual variations in reserves based on such yearend prices are not of consequence in how the business is actually managed. The use of yearend prices for reserves estimation introduces short-term price volatility into the process...(and) is inconsistent with the long-term nature of the upstream business.”

Structured dialogue

The case for modernization appears to be overwhelming. However, amidst a crowded agenda and in the face of the inertia of current practices, change will require continuing effort on the part of all interested stakeholders to maintain the momentum. Without this effort, the required modernization appropriate to today’s industry will remain out of reach.

Change will require a broadened and deepened dialogue among stakeholders and with the policy community. We believe that the process and issues identified in the study, In Search of Reasonable Certainty, provide the starting points for such a dialogue.

The next stage of this effort, which we have just launched, should focus on three initiatives to generate and continue a constructive debate: (1) continued research and workshops to develop and deepen the themes identified in the earlier program; (2) continued dialogue with the policy community to educate its members on the nature of the reserves disclosure issues and their importance; and (3) participation in public and industry stakeholder forums to stimulate dialogue that will continue to develop and amplify the key issues and themes in terms of how the industry operates in the 21st Century.

Key issues

There are a number of primary initial issues a US and international consultative process should address:

• Does the new technical and commercial environment require that the principles underlying the concept of “reasonable certainty” be redefined to reflect the new realities and, if so, how?

• How can one quantify the extent to which technology has altered the level of certainty with which companies determine reserves?

• Is there a different way of presenting reserves data that would better meet the needs of users and provide increased insight into the character of differing assets that are playing increased roles in today’s E&P industry?

• Does the system of reserves disclosure influence industry perceptions of the attractiveness of different petroleum licensing regimes?

Transformational change

The current reserves disclosure system is a classical example of regulations that have become outmoded in the face of technological and market changes. The system evolved out of the coincidence of concerns about energy security, caused by the Arab oil embargo, and SEC’s developing interest in fair value accounting for oil and gas companies.

Responding to the 1973 oil shock, Congress wanted to determine the extent of US domestic oil and gas resources in order to evaluate US vulnerability to new crises. Congress considered assigning responsibility for assessing reserves to a number of agencies and departments. It settled on SEC, which consistently had been cited as one of the most successful of all regulatory agencies. SEC in turn added investor protection to the rationale. It then embarked on a wide-ranging and impressive process of consultation to determine how best to carry out these responsibilities. It also focused on the accounting questions.

The result was a reserves disclosure system that reflected the state of knowledge at the time and consequently had a great deal of credibility. It is striking to consider that there has been no significant reassessment since comparable to the one SEC guided in the 1970s despite the enormous changes in the industry and its capabilities in the 3 decades since. Yet, during this same time the industry has gone through transformational changes that have left the largely unmodified 1978 System behind. That system was created to deal with the realities of what we have described as the “Texlahoma” industry-the composite of the traditional oil patch in Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma that dominated the US industry in the 1960s. The challenge facing the system today is to modernize in order to properly describe the much larger, more diversified, and more global industry of today. At the same time, it needs to remain relevant to Texlahoma.

The transformative changes can be analyzed in terms of four categories-technology, geography, the commoditization of markets, and the character of projects.

Technology. When the 1978 System was adopted, drilling offshore in 600 ft of water was considered frontier. Today, technological advances enable the industry to drill at the frontier of 10,000 ft of water, and another 15,000 ft or more under the seabed.

The industry has a range of technological capabilities, such as attribute mapping of 3D seismic, time-lapsed movies or 4D seismic, and borehole imaging as accurate as a brain scan, that were not available in 1978. The massive increase in computing power-more than a million times over-has enormously enlarged the industry’s ability to gather and interpret data at great depths. As a result, the industry has many ways to assess reserves and is prepared to invest billions on that basis.

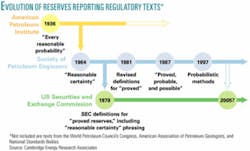

But the 1978 System largely restricts SEC-disclosed reserves to techniques that were state-of-the-art in the 1960s and the 1970s. The fact that the Society of Petroleum Engineers’ 1964 methodologies for determining reserves, which were the basis for the 1978 System, have been modernized while the 1978 System has not demonstrates the growing gap between good practice in the oil and gas industry and the requirements of the current regulatory regime (Fig. 1).

Geography. The 1978 System was put in place primarily to assess US-based reserves. But the geography of the world oil and gas industry has changed. A host of privatized companies, such as BP PLC, Total SA, Statoil ASA, Repsol YPF SA, and Eni SPA, that did not exist as wholly private companies in 1978 are now SEC registrants because of the depth and attractiveness of US capital markets. At the same time, both large and smaller US-based companies have shifted their focus to non-US reserves. As a result, only 17% of the reserves disclosed by SEC registrants are in the US. Among other things, this exposes companies to widely diverging fiscal regimes-for instance, production-sharing agreements (PSA), where reserves go down when prices go up.

Market commoditization. The 1978 System was shaped in a period when the federal government regulated oil and gas prices. The current reliance on yearend prices derived from a concept of prevailing prices that in turn rested on the assumption that, as SEC said in 1978, changes in prices would occur because of “law or government regulation.” Yet in 1983, the year after the codification of this regulatory regime was completed, oil futures contracts began to trade on the New York Mercantile Exchange, and volatility became part of the lexicon of the oil and gas industry.

The 1978 System is out of sync with commoditized markets. The insistence on using the yearend price to value oil and gas reserves is not meaningful and creates confusing distortions for investors. At best, the requirement for yearend prices, in the context of today’s highly traded commodity markets, can only be described as idiosyncratic. The price at the end of the day at yearend is no sure guide either to what happened over the previous year or to what will happen in the next year-or indeed even to what happened on that particular day.

Project character. The scale of projects has grown significantly, and their character has changed. Megaprojects have become much more prevalent. Five years ago, one company had only two projects over $1 billion; today, it has 20-and several are over $3 billion. These megaprojects may involve reserves that can only be determined by highly sophisticated, indirect methods that the 1978 System does not accept. Billions of dollars are going into gas-to-liquid projects and oil sands projects that are focal points of company strategy and spending-and key elements in assuring future supplies-but that cannot be disclosed under the 1978 system.

Potential solutions

The 1978 System is supposed to be based upon the principle of “reasonable certainty.” However, in recent years the requirement for recognizing proved reserves has in practice shifted incrementally-as regulatory rules can-from “reasonable certainty” toward “absolute certainty.” In so doing, a principle-based reserves reporting system has increasingly become a rule-based one, without the kind of transparency and discussion that SEC habitually employs elsewhere.

What must be done? Potential solutions to the emerging strains in the system could include several actions:

• Modernize the rules to reflect the way in which companies view their assets and make their decisions. This would involve adopting industry-accepted methods and technologies upon which companies rely when investing billions of dollars.

• Encourage an open dialogue on industry developments by creating some separation between the functions of making rules and monitoring compliance. This already occurs in accounting matters and could usefully extend to technical matters.

• Assure transparency by making the process for obtaining the regulator’s view on best practices and interpretation of the regulatory regime’s principles open and visible to all participants and to the public.

• Ensure that the rules adapt to industry changes, including fiscal terms (e.g., royalty-tax, PSA, service contracts), operating regimes (e.g., “Texlahoma,” deep water, the Arctic), commercial arrangements (e.g., liberalizing global gas markets), and technical capabilities (e.g., 3D seismic, inferred water contacts).

• Help users of reserves disclosures to recognize inherent uncertainty in reserves estimates. E&P companies recognize that there is uncertainty in a reserves calculation, and they communicate this effectively within their organizations. By contrast, disclosure regulations that create a focus on a single number and imbue it with an almost thaumaturgical significance can prevent this uncertainty from being properly conveyed to and understood by investors and other stakeholders.

• Disclose the basis of assurance that companies use in preparing and disclosing their reserves estimates, without mandating one method or another. Some E&P companies choose to rely on the established competence of their internal estimators. Others prefer to reinforce their internal process by retaining well-respected consultants to evaluate their reserves or publish an opinion of the company’s reserves or its methods. “One size fits all” would be poor public policy. But greater clarity about companies’ preferred methods for assessing their reserves would be helpful to all.

Supply challenges

The 1978 System emerged first and foremost as a response to the energy crisis of the 1970s and to fears about US vulnerability to dependence on foreign energy sources and possible future disruptions. The significant changes in the industry since then make a compelling case for modernizing the system to create a workable, constructive framework for the oil and gas industry in the 21st Century that responds to the needs of both investors and consumers and that does indeed, in a very different world, meet the test of “reasonable certainty.”

This gap takes on increasing importance in light of the major challenge the world oil industry faces in adding new supplies. Over the next 25 years, world oil demand could grow by 40- 50 million b/d-to 120-130 million b/d from today’s 84 million b/d. At the upper end of the range, this would be a 55% increase. This will require tremendous growth in output. The increase alone at the top of the range is almost as much as the total amount the world was consuming at the time of the oil crisis in the 1970s. The actual volume of new oil production will be even larger, to offset declines in existing production in addition to meeting additional demand.

Meeting this level of demand for oil-and for a doubling in demand for natural gas-will require $4-6 trillion of investment in the exploration and production part of the oil and gas industry over the period. It will also require continuing technological advance, innovation, megaprojects, increasing development of “nontraditional oils” and LNG, shifting geography, and flexible markets.

Yet all of these trends are not well accommodated by a 1978 System that is stranded in time-left behind by an industry that has advanced and changed much more than could have been anticipated, or even hoped, in 1978. This innovative capacity is testament to the capability of the oil and gas industry to apply itself on a continuing basis to solving the problems of supplying the world’s energy. The rules need to recognize this capacity for innovation and how central it is to the mission of the oil and gas industry. ✦

Daniel Yergin and David Hobbs are chief authors of CERA’s new study, In Search of Reasonable Certainty: Oil and Gas Reserves Disclosure, an analysis of the problem of and solutions for assessing reserves. This comment stems from conclusions derived from that analysis.

The authors

Daniel Yergin is chairman of Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA). He is a trustee of the Brookings Institution, a member of the National Petroleum Council and the Committee on Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, and serves on the board of the US Energy Association and the US Secretary of Energy’s advisory board. He chaired the US Department of Energy’s task force on strategic energy research and development and is a director of the US-Russian Business Council, the Atlantic Partnership, and the New America Foundation. He has taught at Harvard Business School and the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard. Yergin has authored many works, including Commanding Heights: the Battle for the World Economy, and received the Pulitzer Prize for his book, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power. He received his BA from Yale University and a PhD from Cambridge University.

David Hobbs is director of E&P strategy at CERA, where he has authored several studies focusing on upstream oil and gas commercial development. He leads CERA’s Global Oil Strategy forum. Prior to joining CERA, he had 20 years of experience in international exploration and production, more recently as head of business development for Hardy Oil & Gas. He also has served as commercial manager for Monument Oil & Gas and as drilling engineer with British Gas. Hobbs holds a BS degree from Imperial College.