Land mines, ordnance clearance needed in African exploration

International oil and gas companies are finding countries on the African continent increasingly appealing. That appeal, however, is tempered by dangerous remnants of past wars. Companies conducting exploration in current and former areas of African conflict must be prepared to factor remediation efforts into their plans and costs.

Land mines and unexploded ordnance (UXO), such as grenades, rockets, and ammunition, pose a problem in a number of African countries, many of which lack the capability or resources to conduct clearance operations in anticipation of oil exploration. Exploring in areas that have not been cleared can be unsafe, and exploration companies often must assume responsibility for mitigating the threat.

In such cases, commercial demining and clearance companies serve as alternatives if the host-nation government is unable to provide mine clearance. Securing the services of reputable, effective companies, however, requires research and the willingness to invest time in understanding the problem and the proposed solutions.

Security challenges

Questionable security is a risk in many of the African countries hosting exploration and production by international operators. The dangers posed by paramilitary groups in countries such as Nigeria and Sudan have been widely publicized. In Nigeria, oil operations have been curtailed by violence, kidnappings, and sabotage by warring ethnic militants. In Sudan, civil war has interrupted operations.

A less-publicized but equally serious concern to energy companies operating in Africa is the threat of land mines and UXO. This is particularly true during exploration, when companies are operating away from well-traveled areas and the safety of the land cannot be guaranteed.

Last year in Mauritania, for example, where oil and gas exploration is proceeding rapidly, the staff of a British geological exploration company refused to work due to uncertain information about mine fields in the area.1

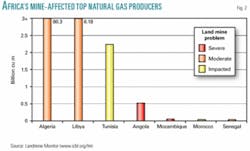

In some cases, land mines also prevent the exploitation of known oil and gas resources. In Egypt’s Western Desert, according to the United Nations, mines and UXO-many dating back to World War II-prevent access to an estimated 4.8 billion bbl of oil and 13.4 tcf of natural gas.

A similar problem exists in Libya along the Mediterranian Sea coastline and in its eastern desert.

Land mine-UXO problem

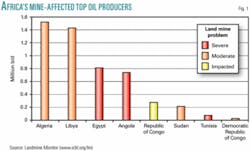

Many of Africa’s top oil and gas-producing countries are among the world’s most affected by land mines and UXO, although the reasons vary widely for each country’s mine and UXO problem (Figs. 1 and 2).

In Angola, for example, the land mine problem stems from many years of nearly continuous fighting, much of it in a civil war among various political parties-principally the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) and the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the current elected government-with degrees of involvement also by both Cuban and South African military units and advisors.

Algeria, Libya, and Egypt, on the other hand, still suffer from the legacy of the battles for North Africa during World War II. In Libya, there also are minefields along the Tunisian border and UXO and mine fields along the border with Chad.

Top oil-producing countries are affected in a variety of ways:2

• Angola. Africa’s second-largest oil producer suffers from one of the most severe land mine-UXO contamination problems in the world. These mines were first used extensively during Angola’s war of independence from Portugal in 1961, and their use continued through the internal civil conflicts until UNITA and others signed peace agreements with the government in 2002. Because so many groups were engaged in laying the mines, the extent of contamination is not fully known. A 2002 report estimated that, nationwide, 4,200 areas were affected. The US Department of State recently estimated that 800 mine casualties occur each year in Angola, and in 1997 the International Red Cross put the number at 1,440 casualties/year.

The effect of mines and UXO, furthermore, extends beyond the human casualty toll. Economic development efforts also are affected. In Angola, the presence of mines and UXO blocks infrastructure development as well as the return of refugees and internally displaced persons in all 18 provinces.

• Algeria. Algeria suffers from explosive remnants of World War II, the war of independence against French colonial rule during 1954-62, and the current insurgency by Islamic extremists. While the Algerian army estimates it has cleared almost 8 million mines in the past 25 years, it also claims that more than 3 million remain. In 2002 alone, mines wounded 44 people. Last year, Algeria asked the international community for mine clearance assistance.

• Egypt. World War II and three wars with Israel have left Egypt with a serious mine problem as well. Official Egyptian sources have estimated that 16.7 million mines affect 2,480 million sq m in the Western Desert, and that 5.1 million land mines affect 200 million sq m on the Sinai Peninsula and along the Red Sea coastline.

In the Western Desert alone, land mines are believed to have claimed more than 8,000 victims since 1982. The impact of Western Desert land mines is being felt keenly as Egypt seeks to implement its North Coast development program involving oil exploration, tourism, and mining development. As with Algeria, Egypt has requested international donor assistance in addressing this problem.

• Mauritania. The National Humanitarian Demining Office (NHDO) of Mauritania estimates that about one third of the country is affected by mines and UXO. This is the result of Mauritania’s involvement in the conflict over a disputed region of the Western Sahara in 1975-78. During 1978-2000, as many as 343 people were killed and 239 seriously injured in reported mine incidents. However, due to the nomadic nature of some Mauritanian people, NHDO recognizes that many mine accidents have gone unreported.

International support

International donors are addressing the problem of humanitarian land mine and UXO clearance, particularly the US-the largest donor to humanitarian demining activities-and the European Union, the United Nations, Japan, and other governments and organizations.

These clearance efforts, however, are almost entirely for humanitarian purposes and are primarily intended to assist in specific programs such as the movement of relief and humanitarian commodities in southern Sudan and Angola, the resettlement of internally displaced persons and refugees in Angola and Mozambique, and the reopening of lands to productive agricultural and other economic development in Rwanda and Mozambique.

However, most of these efforts are government-to-government or similar international assistance. International donors generally do not respond to the needs of commercial companies.

Commercial clearance

As a result, most clearance activities in support of commercial enterprises are expected to fall on host-nation governments or on the companies themselves. Host-nation governments, however, often are not able to provide such support. Either they lack the capability to carry out clearance or their available assets are employed for humanitarian demining.

Thus, energy companies must seek assistance from commercial mine-UXO clearance companies unless they are prepared to provide their own clearance and, in some cases, security capabilities.

Support from such companies is readily available. While it is not inexpensive, its cost is low compared with the cost of oil exploration and development. Energy companies must weigh the cost of clearance operations against the costs incurred in halting work should a worker suffer injuries from a land mine or UXO, said John Wilkinson, a retired Air Force general and the vice-president of Ronco Consulting Corp., a Washington, DC, demining and UXO clearance company working overseas.

“There has been at least one recent instance of an oil company missing delivery deadlines, and incurring significant penalties as a result, because their pipeline-laying operations were halted when a construction engineer was killed by a mine. This occurred on land that had been declared cleared but which, in fact, was improperly and incompletely cleared. Such penalties, of course, can far exceed what a proper and thorough clearance effort would have cost.”3

Due to the nature of their work, clearance companies are accustomed to working in hazardous environments, and most are willing to operate anywhere an energy company would. Commercial deminers, for example, were deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan shortly after the official cessation of hostilities there. Based on their experience in actively conflictive countries, some clearance companies also provide their own security services for both themselves and their clients. In fact, notes Wilkinson, Iraq and Afghanistan have taught many companies that security can no longer be taken for granted, and demining companies are discovering the value of providing security to their operations if only to prevent mines and UXO from being reintroduced into cleared areas.

Unlike mine clearance as practiced by the military, commercial clearance and humanitarian demining are painstaking and thorough processes. In military mine clearance, the emphasis is on penetrating and clearing a way through minefields as quickly as possible, with the expectation that casualties may occur during clearance or subsequent movement through the mine fields.

Commercial clearance and humanitarian demining, on the other hand, stress thorough clearance efforts supported by quality control and quality assurance processes that ensure the safety of large areas of land. Wilkinson said that Ronco, for example, has cleared over 10 million sq m of land in Afghanistan since 2002 under contract to US Central Command infrastructure development projects.

Commercial operations typically use a variety of methods that often are integrated to enhance productivity and ensure safety. Methods include:

• Manual deminers. Trained deminers, wearing personal protective equipment, use mine detectors and probes to detect, inspect, and remove mines. Manual deminers usually operate in squads and move methodically through a suspected area, carefully marking each area, to minimize the possibility of missing a mine.

• Mine detection dogs (MDDs). Technology has yet to replicate the sensitivity of the dog’s nose. Quality, trained MDDs can be the most cost-effective and efficient method of mine clearance. They move at 10 times the pace of manual deminers and are generally more reliable, often following manual deminers to confirm a cleared area. MDDs also are used to verify areas prepared by mechanical clearance methods. MDDs can be trained to detect land mines as well as UXO and are used extensively by some companies for demining worldwide.

• Mechanical clearance machines. Mechanical clearance machines, including armored vehicles, modified tractors, and heavier excavation equipment, sometimes equipped with flails, clear vegetation to improve terrain for manual deminers and MDD teams, speeding demining considerably. For example, Mechem Consultants, a specialized engineering division and subsidiary of the South African state-owned arms company, Denel, is a South African demining company that uses a vehicle that can mechanically “sense” traces of explosives in the air, quickly testing for the presence of mines in a suspected area.

Securing information

Specific information on the land mine-UXO problem in all affected countries is available through the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) in New York (www.mineaction.org) or through Landmine Monitor of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (www.icbl.org/lm).

Information on commercial clearance companies operating in each country and a record of their performance can be obtained from the host country’s national mine action center (if one exists) or from UNMAS. ✦

References

1. UN Mine Action Center report (www.mineaction.org).

2. Landmine Monitor, International Campaign to Ban Landmines (www.icbl.org/lm).

3. Interview with John Wilkinson, Apr. 20, 2005.

The author

John Lundberg, raised in Nairobi, Kenya, is a freelance writer living in Washington, DC. He is a graduate of the College of William and Mary and has graduate degrees from Florida State University, the University of Virginia, and Stanford University. His work has appeared in the Journal of Mine Action, The New England Review, and The Virginia Quarterly Review.