SPECIAL REPORT: Reserves reporting debate stirs movement for reform

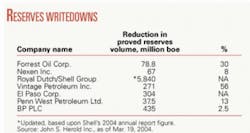

Large reserves writedowns by major oil and gas companies have rekindled debate about how companies estimate reserves, what regulators require of them, and how investors use the information.

While adjustments are a normal part of reserves reporting, disclosure policies drew close attention after Royal Dutch/Shell Group and other companies last year began making unusually large downgrades to their estimates (see table).

Royal Dutch Shell-the largest company making the adjustments-reclassified its reserves estimates five times in a little over a year (OGJ, Feb. 21, 2005, p. 5). The company reviewed all of its reserves estimates worldwide and changed its reserves reporting policy.

During the ensuing public outcry, Chairman Philip Watts and Walter van de Vijver, group managing director and a member of Royal Dutch Petroleum’s board, stepped down from their positions (OGJ, Mar. 22, 2004, p. 31).

The controversy has produced calls for a review of existing US standards and the possible creation of global reserves reporting standards (OGJ Online, Dec. 1, 2004).

Investors’ view

Much of the issue relates to the potential for misinterpretation of information that is both central to the values of oil and gas companies but inherently imprecise.

Matthew R. Simmons, chairman of Houston investment bank Simmons & Co. International, said many investors wrongly assume that proved reserves mean absolutely proved.

He noted that reserves are not precise measurements, such as inventories of manufactured goods. They are estimates-and the numbers are inherently imprecise because of variations among reservoirs.

Despite technological gains, Simmons said, a reserves estimate is akin to an actuarial estimate of a person’s remaining years of life-a scientific guess.

Compounding the difficulty of interpreting reserves estimates is wide variation among countries’ disclosure regulations and what many consider to be excessively narrow disclosure rules in the US.

Reserves reporting rules

Some oil companies complain that US reserves reporting standards are outdated, and some investors complain that the reporting regulations inaccurately reflect corporate value and growth potential.

The Securities and Exchange Commission, which regulates reserves disclosures by companies whose shares trade in the US, focuses on proved reserves, using a definition that has changed little since 1978. SEC Regulation S-X requires companies to report, along with but independent of financial statements, estimates not only of reserves volumes but of present values based on standardized calculations.

The resulting disclosures can differ greatly from the information companies use in their decision-making. Most companies, for example, use different methods of estimating current values of future cash flows. And many of them include probable and possible reserves and apply a definition of “proved” that, unlike the SEC, accounts for technical advances of the last quarter century.

Furthermore, wide differences among countries’ reporting requirements create accounting challenges for multinational oil companies and interpretation challenges for investors trying to gauge corporate performance.

Canadian regulators, for example, mandate the reporting of both proved and probable reserves (OGJ, Jan. 19, 2004, p. 30). UK regulators allow companies more flexibility than US regulators regarding what reserves numbers a company decides to publish in order to give the fullest disclosure.

Analysts and investors are clamoring for broader corporate disclosures to help them determine the significance of reserves reports and to better understand management decisions.

“In more than 25 years, there have been no real changes in [US] reserves disclosure requirements,” said Daniel Johnston, an oil industry consultant and founder of Daniel Johnston & Co. Inc., Hancock, NH.

“Higher oil prices might spur a change because that is what spurred reserve disclosure as we know it today,” Johnston said.

When oil prices soared after the Arab oil embargo of 1973, it was evident that the worth of oil companies’ assets had increased, too. But the “book value on the balance sheets hadn’t even wiggled,” Johnston said. The reason: On their balance sheets, companies report as assets only capitalized costs associated with reserves, which they charge to expense over time on income statements through depletion. Subsequent changes in oil and gas prices have no direct effect on those accounts.

This inconsistency joined concerns already prevalent at the time about the producing industry’s use of two accounting methods: successful efforts and full cost, which differ over whether certain types of cost are capitalized or immediately expensed. SEC’s existing rules evolved from efforts to reconcile those differences.

“The reserves disclosure information has gone through two whole cycles of usage,” Johnston said. “It was used extensively during the merger-acquisition wave of the 1980s. Everybody knew that oil companies were under-valued so corporate raiders took the [SEC Form] 10-K information and recalculated book value.... Company after company changed hands during 1982-84. Billions of dollars changed hands. It was wild.”

During those days, some entrepreneurs used reserves accounting to calculate company values that were twice as high as the company’s stock values, he said.

“After that M&A wave slowed down, people looked around, and they started wondering where all the reserves were. Then, they got psychotic about booking barrels,” Johnston said.

Frederick Lawrence, vice-president of economics and international affairs at the Independent Petroleum Association of America, said, “It is important to the US to become more current and to develop better reserves reporting guidelines.”

Investors are asking companies to provide statistics that offer a better idea of projected production, he said, adding that he is “amazed” that reporting regulations have lagged technological advances.

“Technology has affected how we look at peak oil, how we look at supply projections, and it’s important that reserves reporting regulations use available technology to reflect the financial forward picture of companies,” Lawrence said.

Reserves challenges

Reserves estimates and reporting standards was the subject of a panel discussion at the Offshore Technology Conference in May.

Sandeep Khurana, senior specialist for consultant JP Kenny Inc., told OTC participants that many proposals are reverberating across industry to help clarify reserves reporting requirements.

“SEC proved reserves often lead to poor predictions of production potential or a valuation of the company,” Khurana said. The OTC panel discussion on reserves highlighted the following issues:

- The US Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 seeks a higher level than existed before its enactment of reliability and transparency in reserve estimating and reporting.

- Companies want to link reserves related to a license or production-sharing contract (PSC) with the timing of when they book exploration and development costs. Maximum reserves bookings lead to lower finding and development (F&D) costs and reserves replacement ratios. SEC engineers want conservative reserves reporting so that future revisions will be positive.

- A disconnect exists between capital spent and reserves booking dates.

- Companies worry that SEC regulations limit the ability to fully disclose reserves value profiles and resource portfolios to investors.

- Industry is working to convince regulators of the reliability of current technology.

- Proved reserves quantities fluctuate widely because of unpredictable yearend oil and gas price swings.

Khurana noted that inherent technical uncertainties are involved in the classification of proved vs. unproved reserves.

“The dividing line...is often a matter of professional opinion, and some degree of uncertainty still remains within each defined classification,” Khurana said. “Some degree of error is inherent in the data that are used to estimate reserves.”

Reserves estimates during early field development hinge on volumetric calculations and depend on recovery efficiencies.

“The initial uncertainty often comes in quantifying the oil and gas in place. Even if the oil and gas in place quantity is reliably estimated, the ultimate recovery factor is a continuing unknown because of changing economic and technical variables,” Khurana said.

He said abundant technical and economic reasons necessitate changes and reinterpretations of proved reserves estimates.

Definitions

Ryder Scott Co. LP Chairman and OTC panelist D. Ronald Harrell said he believes most producers find little relevance in the SEC’s reserves definitions.

SEC defines proved oil and gas reserves as the “estimated quantities of crude oil, natural gas, and natural gas liquid which geological and engineering data demonstrate with reasonable certainty to be recoverable in future years from known reservoirs under existing economic and operating conditions.”

For internal corporate planning, many producers instead use definitions jointly agreed upon in March 1997 by the Society of Petroleum Evaluation Engineers (SPEE) and World Petroleum Congress.

“Prudent reserves management requires recognition of proved, probable, and possible reserves, plus identifiable resources,” Harrell said.

Reserves bookings that prove too conservative are just as wrong as reserves bookings that prove too high, he said. SEC imposes a conservatism that does not comply with what many producers consider to be full disclosure.

“Subsequent positive revisions may be comforting but do not get counted in the typical analyst’s metrics in an annual review of a company’s F&D costs,” Harrell noted.

He says it is up to producers to voice concerns to regulators and to initiate change in reserves reporting regulations and standards.

“Consultants and others should remain on the sidelines until such time as they may be ‘invited’ to contribute,” Harrell said. He foresees three possible options for reserves reporting standards.

The first option is no change, which is acceptable to some companies willing to “deal with the devil we know,” Harrell said. The second option is to tweak reporting requirements, and the third option is to start over. “Many producers will be cautious,” he forecast.

Certification programs

Professional associations, meanwhile, are considering a program to certify reserves evaluators. Harrell said he expects any proposed certification program would be optional rather than a form of licensing.

The American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG) and SPEE are expected to reach a decision on reserves evaluation certification this year (OGJ Online, May 23, 2005).

Public companies filing with the SEC during 2004 reported reserves valued at $2.5 trillion, 3% of worldwide reserves, said Dan Tearpock, who leads the AAPG initiative.

“In the US and globally, reserves are not audited by independent accountants and are not estimated by evaluators that have to meet any formal standards,” Tearpock said. “The problem is international in scope.”

Ronald J. Gajdica, BHP Billiton Petroleum Atlantic development manager, said ambiguity in reserves definitions must be removed if certification is to be meaningful.

“The [SEC] rules are not applied consistently,” by companies trying to understand the compliance standards, Gajdica told OTC participants. He noted reserves auditors often differ in their assessments of the same asset.

During the OTC panel discussion, he provided six real-life examples of how earnings fluctuate during the life of a field. The examples showed how conservative treatment of initial reserves estimates amplifies depletion, depreciation, and amortization (DD&A) charges in a field’s early years, hurting its lifetime economic value.

Meanwhile, published statistics obtained through SEC filings can be confusing to investors trying to understand a company’s spending decisions, Gajdica said. Public users of the information lack the producers’ internal forecasts for particular fields.

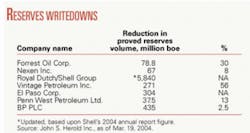

Yearend prices

Some producers suggest that the SEC and the US Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) consider using average prices rather than single-day, yearend oil and gas prices as the basis for calculating estimated reserves reported in 10-K filings.

Financial Accounting Standard (FAS) 69, which FASB adopted in 1982, mandates the use of prices as of Dec. 31 of each year. Producers say this practice distorts estimated reserves volumes and values.

Ryder Scott’s Harrell suggests the SEC announce an estimated yearend price every October, which would give the industry more time to prepare its annual filings. Companies now wait until January to calculate 10-K filings due in March.

The US Energy Information Administration might provide the estimated yearend price, Harrell said, adding that oil companies “universally dislike” using yearend prices as the basis for their reserves and future revenues.

Yearend prices are influenced by seasonality and differ from prices throughout the year (Fig. 1).

Imperial Oil Ltd. blamed the US single-day pricing requirement for its reduction of yearend 2004 proved reserves of its Cold Lake heavy oil operation by 485 million boe.

“The use of prices from a single date is not relevant to the investment decisions made by the company,” Imperial said in a Feb. 18 news release. “Annual variations in reserves based on such yearend prices are not of consequence in how the business is actually managed.”

The yearend cut of Cold Lake reserves didn’t reflect the project’s fundamental economics or Imperial’s positive view, the company said.

“Prices for Cold Lake blend were strong for most of 2004; however, on the day of Dec. 31, 2004, prices were unusually low due to seasonally depressed asphalt sales and industry upgrader problems in Western Canada,” Imperial said.

Other Alberta oil sands producers also commented on price differentials between bitumen and benchmark light crude prices. Bitumen prices were higher before and after their yearend level.

Nexen Inc. of Calgary wrote off proved heavy crude reserves at its Long Lake oil sands project to meet SEC rules, adding that the revision had no effect on the project.

Husky Energy Inc. said prices for heavy crude were $12.27/bbl on Dec. 31, 2004, compared with a fourth quarter average of $25.91/bbl.

“At $12.27/bbl, 86% of our proved undeveloped heavy crude oil reserves in the Lloydminister area did not produce positive cash flow,” the company said in a Jan. 17 news release. In accordance with SEC regulations, heavy oil was subtracted from proved reserves until prices increased sufficiently to return those reserves to economic status.

The Alberta Securities Commission allows Canadian filers to use an average annual price for bitumen instead of a yearend price.

Consultants agree with producers about single-day, yearend pricing.

Khurana said the SEC’s Dec. 31 pricing requirement creates “a snapshot view of reserves and calculated values assuming those prices and costs pertain for the entire reserve life.”

Deloitte & Touche LLP suggests that the SEC allow price assumptions that are consistent with a company’s budget (OGJ, Mar. 21, 2005, p. 26). Cambridge Energy Research Associates calls “the volatility of yearend pricing...a source of frustration for companies and investors alike (OGJ, Mar. 7, 2005, p. 31).”

International differences

The reserves disclosures of international companies are further complicated by great differences among the disclosure requirements and fiscal regimes applied around the world.

“Unfortunately, when it comes to international reserves values, nobody seems to speak the same language,” said Johnston.

A company’s value of reserves often is based on gross recoverable reserves or working-interest share of reserves. Depending on the fiscal system, reserves reporting and liftings are based on net-revenue-interest barrels or contractor entitlement.

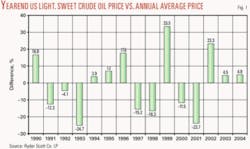

A large percentage of many large producers’ reserves are subject to PSCs, the terms of which are distinctive because the host government owns all the reserves and shares the production with participating oil companies.

A company’s PSC entitlement factors in cost recovery, which is tied to oil prices. As prices fluctuate, the entitlement can change dramatically. Ironically, a company’s reserves booking go down when oil prices go up.

“That just doesn’t seem quite right. It only happens under PSCs,” Johnston said. “For example, if the oil price drops, the entitlement will increase. This is because the contractor’s entitlement equals the contractor’s share of profit oil plus cost recovery. This points out a key weakness of reporting entitlement reserves.”

PSC terms restrict an oil company’s ability to book reserves under current SEC rules, Graham K. Kellas, Wood Mackenzie vice-president of petroleum economics, wrote in a research report “The Pitfalls of Windfalls: Oil Price Volatility, Fiscal Stability, and Booking Reserves.”

Companies appear to “lose barrels as the oil price increases,” Kellas said (Fig. 2).

Canada, UK regulations

UK and Canadian regulators have been more progressive than US regulators in working with oil companies on reserves disclosures, consultants agree.

“The British have given management a little more latitude as to what kind of price they can pick,” for calculating reserves values and future cash flow, Johnston said. “The British also allow companies to book proved and probable barrels. The US requires proved reserves only. It’s about time for the SEC to move beyond that.”

Derek Butter, WoodMac analyst, noted that the UK Financial Services Authority uses a Statement of Recommended Practice (SORP).

“Basically, the oil industry put together guidance on oil and gas activities and companies’ accounting practices. That also covers how people should treat reserve bookings,” Butter said. “SORP tries to ensure that companies give a fair view of reserves.”

BP PLC last year filed different reserves reports in the UK and the US, with disclosure of both proved and probable reserves in the UK filing.

“The SEC guidelines were getting too far from what BP regards as a fair view of their reserves,” Butter said. “I think the [SEC] reserves information at the moment is just too constrictive.”

He endorses the concept of reporting both proved and probable reserves-the practice in Canada.

David C. Elliott, Alberta Securities Commission senior petroleum evaluation geologist, said the ASC is monitoring the volume of revised reserves reporting standards implemented under National Instrument 51-101.

The ASC focus is on proved and probable reserves, although producers can elect to report proved, probable, and possible reserves. And unlike the US, most Canadian producers are required to have a third-party reserves evaluation.

“This is the first year of reporting...and there has not been sufficient time for any trends to be established, but it is notable that the number and volume of negative revisions are higher than expected,” Elliott said.

So far, ASC statistics show 2003 average technical revisions as a percentage of opening reserves were -0.4% for proved and probable reserves for 138 companies. Revisions were as high as -19.7% for proved heavy oil estimates and -14.9% for proved and probable heavy oil estimates. A total of 44 companies provided heavy oil estimates.

Canadian reserves reporting regulations probably will not be revised again until a number of reporting cycles have been completed, Elliott said.

Standardization

To address international inconsistencies, the SPE is working with the AAPG, the World Petroleum Council, and others under United Nations auspices on worldwide reserves classification.

Thomas S. Ahlbrant, the US Geological Survey world energy project chief and vice-chairman of an ad hoc reserves classification group for the UN, said the UN Framework Classification for Energy and Minerals Resources has integrated classifications from the SPE, WPC, and AAPG into its reserves categories.

Ahlbrant said the UN is examining other countries’ classifications, including Norway’s, to document common definitions and to facilitate international financial reporting.

WoodMac’s Butter emphasized the need for “a comprehensive, universal set of rules for booking reserves” and for standards that help investors compare companies.

“When you’ve got one company’s produced set of reserve numbers, you want to know that it’s [presented] on exactly the same basis as another company’s,” Butter said.

He noted that the accounting industry has adopted some general practices globally.

“There is no reason why you couldn’t have a commonly understood method of booking reserves applied to companies operating in the main areas of the UK, the US, Canada, and Australia,” Butter said.

He suggested that a possible catalyst would be “if the US government got involved in this debate and basically twisted the arm of the SEC to deal with this issue by sitting down with the companies.”

Johnston expects a global resolution to reserves reporting definitions and procedures.

“There always will be some problems, but I think that we are going to have better standardization,” Johnston forecast.