CASPIAN OIL OUTLOOK-1: Caspian oil not likely to fill market void or depress prices

A revival of the 19th century “Great Game” has been playing out over the past decade for control and development of untapped oil and gas resources in and around the Caspian Sea.

How much of this oil rush is just hype, and how much will actually come to global oil markets?

Here are the main conclusions from a close look:

- The Caspian basin, full of uncertainty but with alluring oil production potential, continues to be a hotspot for international oil company (IOC) investment, while Western policymakers are counting on the region to emerge as a new oil supply center and bring down soaring oil prices.

- A lack of oil export infrastructure and a continuing dispute over the legal status of the Caspian have proven obstacles to greater oil production from the region, although the war for pipelines is largely over.

- Kazakhstan, with its massive offshore Kashagan field, symbolizes both the hope and frustration of doing business in the Caspian region as the Kazakh government increasingly takes a harder line with IOCs eager to exploit the country’s vast natural resource wealth.

- Azerbaijan, formerly the Caspian’s star attraction, is increasingly dependent on one major project to fuel its future oil production growth, meaning the country’s coming oil boom could be short-lived.

- Turkmenistan, Russia, and Iran are comparatively less advanced in developing their Caspian oil reserves; Turkmenistan, with its shoddy investment climate, will see its future oil production growth limited, while Russia is in the early stages of exploration and development of its sector of the Caspian, and Iran remains stuck in a failed policy position on the division of the sea’s hydrocarbons.

- Future Caspian oil growth will certainly see the region emerge as a source of new oil for global markets, but the projected output from the region will have little impact on prices given current demand trends and declining output from other established oil provinces.

Prince Caspian to the rescue?

Nearly 14 years since the collapse of the Soviet Union created four new countries with borders on the Caspian Sea, much more is known about the region, especially its oil and gas potential.

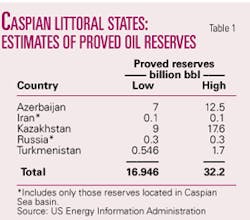

Yet while Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan are on the radar screens of western policymakers mainly due to their hydrocarbons, still maddeningly little is known about the countries’ actual proved reserves (Table 1).

While Russia and Iran, the other two Caspian littoral states, are well-established oil producers on the global stage, the combination of alluring production potential and uncertainty in the remaining three has given the Caspian region added importance in geopolitical circles and global oil markets.

Hence, a new version of the 19th century “Great Game”-in which Britain, Russia, and China competed for influence in Central Asia-has played out since the USSR’s demise, except this time the focus has been on the Caspian Sea, with players vying for access to and control over the development of the region’s oil and gas resources.

It now involves international oil companies (IOCs), the littoral states, and even distant governments in the US and Europe. A flood of foreign investment has poured into the Caspian region, especially into Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, since the Soviet collapse in 1991. All expectations are that this investment will soon pay off when the region begins pumping out oil exports and becomes a new supply center for global oil markets.

The question is, how much oil can actually be extracted from the Caspian basin? By now, we know that the Caspian region is definitely not a “new Middle East” for oil production as it was touted in the early 1990s.

Estimates of the Caspian’s oil reserves vary widely, although it is generally believed that the basin contains in the range of 16 billion to 32 billion bbl of proved (i.e., economically recoverable under current operating conditions) oil reserves. This puts the basin on a par with the North Sea, or Qatar at the low end of the estimate and the US at the high end.

Why such debate about the size of the Caspian’s reserves? The volume of reserves determines the amount of oil that can be produced from the basin. This in turn will determine how much “new oil” flows onto the global market from the Caspian basin and whether this will have a substantial enough effect to bring down global oil prices, serve to balance the market as consumption continues to rise, or merely replace declining production from established oil basins and have little if any impact on the oil market.

Shifting oil markets

With oil prices again setting new records and threatening to crash through the $60/bbl mark, there is intense interest in new Caspian oil production and its potential to help meet soaring demand.

The high prices and tight supply/demand balances have raised the notion that “the end of cheap oil” is already upon us.

In October 2004 when oil prices hit record levels, traders and oil companies attributed the price spike to production disruptions from hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico as well as problems with key suppliers Norway and Nigeria. Yet the resurgence in oil prices to record levels in the first quarter of 2005 has no such parallel explanation.

While industry giants such as BP and ExxonMobil continue to insist that current prices are merely part of the natural ebb and flow of markets, there is a growing belief-and evidence to support it-that the oil market has shifted to a new, higher-price equilibrium.

For one thing, OPEC essentially abandoned its desired price band of $22-28/bbl long before the organization formally scrapped the price target range. The cartel’s decision not to open the taps further when prices soared above $50/bbl in October 2004 reflects not only OPEC’s tacit acceptance of higher prices but also a lack of spare production capacity to mitigate price rises. OPEC now appears content with a price of $50/bbl at the high end of a new price target range.

Fundamentally, in the absence of a production disruption or a singular event that is providing a floor for prices above $50/bbl, it appears that there may indeed be a new oil price paradigm evolving. Support for this view also comes from the activities of oil companies themselves.

Growing competition between IOCs and national oil companies (NOCs) is putting a premium on access to reserves, yet even with today’s “high” prices, most IOCs are turning to stock buybacks and acquisitions rather than investing in new exploration.

This suggests that, in addition to the increased political risk in investing in unstable countries, there just isn’t all that much more new oil out there to be found. There has been a distinct lack of “elephant” oil field discoveries around the globe in the past 5 years.

Chevron’s $18 billion acquisition of Unocal points to an acceptance by the No. 2 US supermajor that the “high” oil prices of today are more likely to be the “normal” prices of the near future. The decision to invest in proved reserves and acquire Unocal’s asset portfolio speaks not only to Chevron’s need to boost sagging production but also to the company’s apparent belief that the acquisition will be cheaper-and more successful-than investing a similar amount in new exploration.

All signs are that Chinese demand will continue to grow while the US government continues to focus more on supply side measures such as tapping petroleum reserves in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Consumption will continue to outpace production, creating a steadily rising floor for world oil prices.

Already key oil producing nations have increased their base price budget assumptions for oil export revenues, and most IOCs have hiked the price on which they base their annual investment programs.

Hence, supply needs to continue to grow if it is to keep the current market stable and prevent further price increases. Yet with the expected decline in North Sea volumes and the continued dwindling of US production, consumers will have to look further afield to more risky oil provinces for the new oil to balance out the global market.

New production centers are emerging in West Africa and the Caspian region, while established producers in the Middle East and Russia gain in importance. Before the Caspian region can truly make an impact on the global oil market, however, two obstacles remain in the way: the lack of infrastructure to deliver this oil to major consumers and the failure of the littoral states to agree on the legal status of the Caspian Sea.

Pipeline politics

A key component of this new “Great Game” has been the undisguised political battle to construct pipelines to export the region’s oil supplies to markets.

The US government, in particular, has played a leading role in swaying IOCs and regional governments to build pipelines that not only avoid Iran-thereby denying the Islamic Republic economic benefits from oil transit revenues-but also do not cross Russian territory.

The second aspect of this policy is not intended to be “anti-Russian” so much as it is ostensibly “pro-independence” for Azerbaijan, cementing the country’s newly established freedom with an export outlet beyond Russian control.

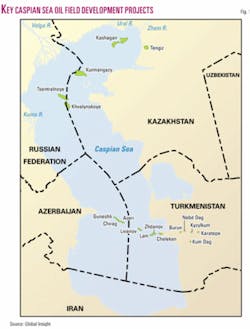

Thus, more than a decade since the end of Russia’s domination over Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan, some Azeri oil is already being exported to world markets via Georgia. The big increase will begin later this year, however, when oil from the 1,770-km Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline comes onstream after a decade of strategizing, politicking, planning, and finally construction.

The 1 million b/d BTC pipeline is expected to serve as Azerbaijan’s main conduit for oil exports from the Azerbaijan International Oil Co.’s (AIOC) output at the Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli (ACG) group of fields. Kazakhstan, too, is expected to export some oil via barge across the Caspian for reloading the further transshipment via the BTC pipeline.

Kazakhstan has played the game well, keeping its export options open by appeasing the other players and seeking to diversify its export routes.

Although the central Asian republic has reinforced its dependence on Russia for oil export transit services via the 1,580-km Caspian Pipeline Consortium’s (CPC) Tengiz-Novorossiisk pipeline, it is also engaged in building a pipeline link to China. The Kazakhstan-China pipeline is under construction and expected to be operational by 2006.

Meanwhile, as the 565,000 b/d capacity CPC pipeline has run into Russian opposition, preventing an early expansion to its peak design capacity of 1.34 million b/d, Kazakhstan is seeking to build perhaps yet another export pipeline and has not ruled out a link to Iran via Turkmenistan or the Caspian Sea. Kazakhstan is already engaging in relatively low-level oil swaps with Iran, but these could increase.

With the CPC in place, the BTC about to come onstream, and the Kazakhstan-China pipeline under construction, the battle for Caspian region pipelines is largely over (though there appears room for perhaps one more pipeline to offtake additional Kazakh production unless one of the existing routes is expanded). As such, the competition has shifted somewhat to focus on rail oil transit, which will remain an important export vehicle for Azeri and Kazakh oil supplies as well as, in all probability, the main export outlet for Turkmenistan.

In addition, even before the bulk of Caspian oil exports begins to flow, there is already a cottage industry for “Bosphorus bypass” pipelines.

As additional Caspian oil flows westward from Black Sea terminals at Supsa and Novorossiisk, Turkey’s concerns about oil tanker traffic in the narrow Bosphorus Straits have precipitated the tightening of environmental regulations in the straits as well as a move by Black Sea littoral states to redirect this Caspian crude to European markets via their territory. Several such routes are in development or under consideration, while Ukraine’s Odessa-Brody pipeline is already available for potential use, although it is operating in a temporary reverse regime until 2008.

Legal stalemate

While the Caspian region is moving closer to resolving the problem of its lack of export outlets for rising oil production, the littoral states appear no closer to settling their longstanding dispute over the legal status of the sea.

This uncertainty remains a serious impediment to improved relations between the five littoral states, as well as a hindrance to the development of the sea’s natural resources.

High-level officials from Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Turkmenistan continue to participate in working groups geared to settle disagreements and eventually establish a legal framework governing the sea, but thus far there has been only limited progress towards a multilateral solution.

NEXT: Caspian countries pursue oil exports at greatly varying paces.

The author

Andrew Neff ([email protected]) is a senior energy analyst at Global Insight, focusing on the Commonwealth of Independent States, the Baltics, and Balkans, with special emphasis on Russian and Caspian Sea oil and gas. Before joining World Markets Research Centre (now Global Insight) in 2002, he worked as an international energy analyst, first from Washington, DC, then from Kiev, Ukraine, for a contractor to the Energy Information Administration, the statistical division of the US Department of Energy. He holds an MA in international affairs and environmental policy from George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs.