AMSTERDAM CONFERENCE—1

Drilling industry leaders spoke out during plenaries at a recent conference about responsibility for new technology development and the causes of commercial failures of some new technologies despite technical successes.

More than 1,500 people participated in a drilling conference held in Amsterdam in late February, sponsored by the Society of Petroleum Engineers and the International Association of Drilling Contractors (IADC), featuring more than 100 technical papers and presentations. Among the highlights of the conference were three plenary sessions featuring panel representatives from operators, drilling contractors, and service companies. Attendees weighed in on dozens of questions using wireless voting pads. Each plenary session lasted about 2 hr.

This article presents the highlights of the first two sessions, representing about 4 hr public discussion among industry leaders. The concluding article, next week, will review the third plenary session on mature well technologies.

Mike Harris, conference chairman and director of worldwide drilling at Apache Corp., noted in a letter to delegates, "The shift in responsibility in technology development and deployment from operators to suppliers has been a fundamental change in our business. All sorts of issues have emerged concerning the costs, stewardship, and ownership of technology in the E&P sector."

Who should pay?

The first plenary session, "New Technology Development—Who Should Be Responsible?" was moderated by Toni Marszalek, vice-president at Schlumberger Ltd.

The panel included Tony Meggs, group vice-president of technology at BP PLC; Satish Pai, vice-president at Schlumberger Oilfield Technologies; Paul Ching, director of E&P research and development at Shell Exploration and Production Co.; Kevin Lacy, vice-president and chief technical officer at ChevronTexaco Corp.; and Steve Newman, vice-president of performance and technology at Transocean Inc.

The session addressed issues surrounding development, funding, and deployment of drilling technologies, touching on multichannel seismic, directional drilling, drilling costs and contracts, collaboration and "strategic alignment" relationships, newbuild rig economics, and venture capital (Table 1).

Schlumberger's Pai cited a Bank of America analyst who said that it made no sense for anyone to invest in seismic technology. BP's Meggs said that the seismic market is flooded and that low barriers to entry in that industry ruin the profitability for established companies.

Directional drilling technology has taken an inordinate length of time to be used, Pai said, citing the historical development from first-generation MWD tools and steerable motors developed by oil companies, to first generation LWD services developed by contractors, followed by geosteering, and rotary steerable systems.

Meggs said that when the need is there, the pace of technology development is rapid. He noted that there are always internal barriers in companies, however.

Chris Carstens from Unocal Corp. asked the panel how an operator reduces drilling costs, given the shift to service side maximizing profits and margins.

BP's Meggs said "we all need to pay," but followed that with the assertion that reducing drilling costs benefits everyone. He said that operators should not spend less on drilling but should drill more holes with the same money, using Prudhoe Bay unit drilling as an example. The company spent about $7 million/well in 1984, using conventional drilling, but began using coiled tubing around 1990 and now spends about $1.5 million/well.

Collaboration

Although it's viewed as a mega-company, Meggs pointed out that BP produces only about 4% of the world's oil and gas and therefore is very interested in collaboration in the right circumstances. He sees clear roles for partners:

- Operators: Provide resource, define the problem, provide a test bed for field trials, and take project risks.

- Service companies: Provide a customer base (economies of scale are important), provide design skills and manufacturing capability, and take market risk.

Citing a recent example of expandable completion systems designed by Weatherford, Meggs said the sand screens were a great breakthrough in isolating producers and injectors in South Texas. Zonal isolation tests were successful after about 18 months' development.

Moderator Toni Marszalek asked the panel how long strategic alignment lasts. Paul Ching (Shell) felt that alignment remains focused over the short term, about 2 years, but changes during 10-15 year development projects. Meggs said that alignment could remain over a multi-year period as long as the collaboration stressed technology themes that focused on business needs.

Kevin Lacy, ChevronTexaco, said that best-in-class (top quartile) performance is found through superior partnerships. Although operators play a central role, working with resource owners and consumers, drilling contractors, and service companies, an operator is the ultimate "middleman" and not in control of market forces.

Lacy said that two big negative trends in the industry are the short-term business model used with suppliers and contractors, and the focus on operating expenses rather than net present value (NPV). To rectify the damage, he suggests:

- Advising management to take advantage of new well technologies.

- Developing broad technology portfolio and project plan.

- Completing revision of supply-chain business model.

- Developing partnerships with multiple-year horizons.

- Removing or reducing internal company barriers.

Most of ChevronTexaco's contracts in the last 3 years have stipulated a rate floor and provided for a performance bonus, Lacy said.

Rig economics

Steve Newman, Transocean, focused on the drilling contractor's perspective in the first plenary session. He noted that new rigs built at a cost of $350 million are being leased in 5-year contracts at rates of about $200,000/day. For appropriate return and capital efficiency, contract rates in the sixth year after construction would need to be about $275,000/day.

Newman said that developing new rig technology presents challenging economics, because of ill-defined specifications, serial number one design, fabrication and commissioning requirements, and questionable project management.

Who or what is to blame for the vagaries in the drilling market?

The market is what the market is, he said. Day rates are not set by return on capital criteria. Drilling contractors do not always act rationally in building new rigs, and operators are excellent at exploiting this weakness. The cyclical market for oil and gas magnifies the pain.

Lacy agreed that there are many disconnects in the drilling market. An example, Newman noted, is that North Sea mid-market rates are rising steadily, despite some rigs sitting idle, reflecting good discipline on the part of the contractors to keep some rigs stacked.

Ching said that Shell relies on the market, and that the company has had many instances of collaboration with drillers to improve rigs, funding the cost of upgrades, the value of which remains with the contractors.

Meggs said the cost of drilling is a large component of BP's current projects in the Gulf of Mexico. It's a challenge for project planners to develop acceptable rates of return. "Having efficient drilling costs is a very important part of making projects economic," he said.

Evolutionary, revolutionary

Satish Pai, Schlumberger, described "evolutionary" technology as low risk with a consistent, predictable value addition, citing through-tubing rotary steerable systems as an example. He noted that it addressed a specific industry need, and BP, Shell, Statoil ASA, and Schlumberger funded the R&D.

In comparison, Pai described "revolutionary" technology as high risk and unpredictable, citing seismic-on-pipe for well placement as an example. Although the technology has been available for years, it has never been adopted into the mainstream, and the number of jobs performed is almost equal to the number of technical papers published.

Pai said that technology development crosses section boundaries and stressed the value of the role of entrepreneur or technical champion in an organization. "The industry must recognize the value that differentiated technology brings and the associated cost to give service companies incentive for more research and development."

Are we doing enough? Pai said operators should:

- Accept greater risks to develop revolutionary and evolutionary technologies.

- Shorten the time cycle; adapt technology sooner and leap the chasm between the visionary early adopters and the later-adopting pragmatists.

- Recognize the value of differentiated new technologies.

New ventures

Paul Ching, Shell, referred to a McKinsey study that noted the particularly slow pace of innovation in the oil industry compared to other industries. It was found that new technologies required 25-30 years to become mainstream, and rapid innovation was the exception, rather than the rule.

Ching sees emerging "short-termism" in the E&P industry. These days, he says, a year is a long-term commitment. The markets and analysts are forcing major oil companies to focus solely on short-term performance, rewarding only quick commoditization of technology, and cutting costs versus adding value.

Realignment is required. Innovators need a return on investment. Major operators want exclusive use of technology, while service companies want to sell broadly and maximize profit, he said.

Shell Technology Ventures Inc. was established to cross the chasm between early and late adoption of technology. Its purposes are to spin out selected disruptive Shell technologies, create new entrepreneurial companies, and follow a venture-capital approach, linked to R&D.

Ching cited the example of expandable technology, developed at Shell in 1993-97. The screens were licensed to Weatherford in 1995, and the new company Enventure GT was created in 1998-2001, in equal partnership with Halliburton. However, Schlumberger expressed concern that its customer, Shell, now owned part of a large competitor.

Commercial failure

Terry Lucht, manager of drilling engineering and operations upstream at ConocoPhillips, moderated the second plenary session, "Drilling Technologies—Failure or Just Ahead of its Time?"

The panel included Jon Marshall, president and CEO of GlobalSantaFe Corp.; Randy Kubota, general manager of drilling and production systems at ChevronTexaco; Kyle Fontenot, onshore Gulf Coast drilling manager at ConocoPhillips; Graham Robinson, wells manager for Shell UK Exploration and Production Co.; and Tim Probert, senior vice-president of the drilling and formation evaluation division, Halliburton Energy Services Group.

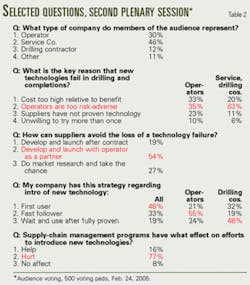

The session focused on commercial success and failure under different business models, funding, and commercial arrangements, including supply-chain management programs (Table 2).

Tim Probert believes that technology is the key to our future and that companies must innovate more quickly to stay successful. Operators are challenged by smaller accumulations and faster decline rates, and yet he sees them in a "mad rush to be second," adopting and deploying new technologies only after fully proven.

In 2004, based on percentage of revenue, the top seven users of new technology were independent operators, and the eighth was a turnkey drilling contractor, Probert said. Would there be fewer commercial failures if major operators were more willing to try them in the field?

Why do R&D projects fail?

Probert suggested that projects are not subject to strict economic scrutiny and are not killed or shelved at the appropriate time; that developers fall in love with their own ideas in their creative zeal; that service companies may listen too closely to customers or overdesign solutions that are inappropriate for the value point.

The industry is conservative, Probert said, "We killed all the unbridled optimists long ago."

Halliburton's short-chain micropolymer (HMP) is an example of an unexpected commercial failure. It consists of chains 20-30 times shorter than standard polymer gels but is sidelined as a niche product due to the cost and high-friction behavior. But Probert noted that the research has led to many spinoffs.

New technologies are successful when there is a rich dialogue between the developers and end users, a robust design effort that balances needs and costs, and versatile integration with existing systems. Real-time operation centers (RTOCs), for instance, were introduced in the mid-1980s but were not commercially successful until they integrated collaborative workflows, Probert said.

Voting results showed that conference delegates representing both operators and service companies agreed that the key reason new technologies fail is that operators are too risk adverse (Table 2).

Jon Marshall, GlobalSantaFe, said that although we speak of it pejoratively, risk aversion is natural. Just as living organisms survive by avoiding risky behavior in their environment, business entities tend to avoid risks in the marketplace. This industry "does not have a high tolerance for failure," he said. Still, the real risk for operators is in locating the wells; taking risks while drilling is secondary, he maintains.

A representative from Petroleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA) asked the panel if risk aversion was affected by knowledge. Fontenot said that knowledge transfer is a "metric" at ConocoPhillips. Marshall said that contrary to what might be expected, with less knowledge, companies are less risk-adverse. Companies are more courageous "when we don't have an abundance of knowledge," he said.

Shell's scallop

Graham Robinson, Shell UK, said that technological capability is implemented through Shell's realizing the limit initiatives (RTL) and opportunity realization processes (ORP). These processes lead to improved cultural acceptance and improved deployment of new technologies.

The downside, Robinson noted, is the supply-chain management system, which works the margins and makes commodities of technologies. There is a growing realization that it both suppresses new technologies and breaks relationships with suppliers.

Many speakers in the three plenary sessions expressed disenchantment with supply-chain management, suggesting that price should not be the sole determinator in technological development and deployment. Probert noted that supply chain pushes toward parity, but "we need more balanced metrics, incorporating the value of innovation."

People factors may also depress innovations within work teams, where the threat of failure outweighs the potential for success. Partners may also bring risk-adverse behavior. Robinson cited the limited use of expandables in the North Sea. He thinks the technology failed to take off because of early failures and high costs.

Fontenot said that corporations sometimes build barriers that stymie engineers from using new technologies, and Robinson suggested that KPI scorecards might have a negative effect.

Robinson cited Shell's adoption of light, hydraulic land rigs in the Netherlands as an example of a good project that was successfully implemented, due to management support and an appropriate reward system. "What makes the difference is the leadership, having the right champion."

Management support

Fontenot said that operating company leaders could help by:

- Creating an environment that spawns step-changes.

- Defining a problem, creating a sense of urgency that challenges a breakaway team.

- Identifying and utilizing change agents—people who push the status quo.

- Encouraging well thought-out risks, cheerleading (protecting), rewarding, and recognizing positive efforts.

- Removing hurdles and roadblocks, understanding the time frame.

An example of management's patience with a new technology, he said, was ConocoPhillips' five-well program to evaluate casing drilling in South Texas. A typical well took 22 days to drill but the first two wells drilled with casing required 46 and 44 days before the drilling teams mastered the technique.

Robinson cited Shell's adoption of swellable packers in the UK as another successful new technology venture.

Probert said it has become more difficult to get products placed and tested, unless there is a champion at the operating company. Operators forego the opportunity to try a range of technologies at low cost and limited risk. Fontenot explained that operators want predictable results, but he favors budgeting for at least one or two wells per hundred drilled to test step-change technologies.

Marshall doesn't see drilling contractors as leaders in technical innovation, but rather as integrators of technologies created by others. Larger top drives and pumps have not fundamentally changed the industry, he said.

Technology deployment

Randy Kubota, ChevronTexaco, said "deployment" includes technical knowledge applied to field operations, using skilled employees, and updating software and equipment designs. Successful deployment is defined by:

- Multiple, repeatable operations.

- Field personnel actively involved following proof of concept.

- Active QA-QC in manufacturing.

- Pilot test of equipment before full field implementation.

- A system integration test (SIT) of the full field model.

He noted ROP prediction software as an example, although there are frustrations concerning performance in intelligent wells, multilaterals, and dual-gradient drilling in deep water. Probert noted that Norway has a high percentage of multilateral wells, and Fontenot lamented that technologies have to be reproven in different areas, by different operators.

Industry decapitalization

Jon Marshall, GlobalSantaFe, noted several impediments to technological progress:

- Economic largesse does not encourage innovation; profitability creates risk aversion.

- Potential funding for technology is reduced by decapitalization—companies removing billions of dollars while buying back stock.

- Geopolitical issues limit areas open to exploration.

- Equity markets push behavior not conducive to technology investment.

Marshall noted that technology improves more during down cycles. Reserve replacement was 150% in 1998, but is now 100% or less. If oil prices remain stable, there is no room for technology growth, and if oil companies fail to grow, they become nothing more than royalty trusts, he said.

Probert noted that average R&D spending by operators is about 0.8% of revenue, while service companies spend 2.5-5% of revenue. Kubota noted that some projects are fast-tracked due to infusions of capital, such as ChevronTexaco's Tahiti project in the Gulf of Mexico. The technology necessary to develop the high temperature, high-pressure field was built in only 2 years. The company's budget for new technology increased 65% in 2003-04 and will increase further in 2004-05.

Projects that meet corporate goals are seldom optimized, the panel agreed. If you reach a 20% rate of return, why not take steps to reach 40%?

Correction:

An oil volume in the article "DOE technology manager lauds microhole technology" (OGJ, Feb. 21, 2005, p. 48) was incorrect. Here's the correct version: There are 218 billion bbl (rather than million) of oil, located 5,000 ft or shallower that is nonrecoverable with current drilling and production technologies.