Russian production growth pushes infrastructure needs

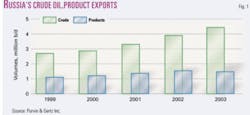

The rapid development of the Russian oil companies into well funded, market-focused international players and international investment in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan has led to a rapid growth in crude oil production (Fig. 1).

High oil prices have also helped generate the massive funds needed for infrastructure development and have made economic additional exports of crude oil by rail and barge.

Crude oil exports from the CIS (Russia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.) have increased to 4.7 million b/d at yearend 2003 from 2.7 million b/d in 1999.

At the same time, product exports from Russian refineries have also grown to more than 1.5 million b/d.

Crude oil

Almost all the Russian, Kazak, and Azeri crude oil supplies are produced at great distances from export terminals.

An extensive pipeline network of almost 50,000 km operated by state-owned Transneft transports the crude oil to domestic refineries and export points. Transneft is rapidly adding the needed pipeline and terminal facilities to increase crude oil exports by relieving the existing transportation bottlenecks.

Short-term expansion projects include expansions at Primorsk in the Gulf of Finland and reversal of the Adria pipeline to allow exports the Croatian port of Omisalj (OGJ, Oct. 6, 2003, p. 62; Mar. 3, 2002, p. 64). This route will provide the first port that can load Russian crude onto VLCCs.

A new 3,500-km pipeline and terminal at the ice-free port of Murmansk for crude oil and a new line to China and possibly the port of Nakhodka, Japan, are also under consideration. Exports from Sakhalin Island are also scheduled to increase significantly.

In the meantime, oil producers will continue to rely on more expensive rail and barge options to export the crude oil in excess of pipeline capacity.

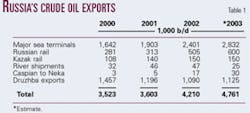

Crude oil exports to non-CIS countries by sea account for the largest volumes, while pipeline deliveries to central Europe via the Druzhba pipeline have not increased in recent years.

Several changes to the pipeline network in central Europe are planned, however, that would increase markets for Russian crude. The Transpetrol system through Slovakia is to be extended to the OMV refinery in Vienna. In addition, the IKL pipeline that feeds the Czech Republic is to be made bidirectional, allowing Russian crude to flow to south Germany.

Apart from these changes, most of the increase in crude oil production will be exported by sea (Table 1).

The key infrastructure developments necessary for exports to increase rapidly from current levels are the completion of the Baku-Tiblsi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline and the Murmansk terminal and associated pipeline system.

The 1,600-km BTC pipeline is under construction, but the Murmansk project is still under consideration. To increase exports further, new crude oil pipelines to China and (or) Japan will likely be built. If they become viable, new reserves will need to be developed to provide crude oil for export.

Products

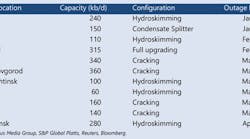

Product export facilities are more limited.

Currently, most of the products exported move by rail from refineries in the interior of Russia to ports in the Baltic or Black Sea. The high transportation cost and resulting low netback from these product exports can be economically justified by the low price of domestic crude in Russia.

Domestic crude oil prices to refineries are low because of the high cost of incremental exports by rail and barge. As crude oil pipeline and terminal constraints are removed, however, these high incremental logistics costs will be reduced, and Russian product exports will become less attractive than crude oil exports, unless product export infrastructure is also added.

This potential change in the economics of Russian petroleum exports would have a major impact on the marginal refineries in Russia and on the European refining industry (Fig. 2).

For more than a decade, the structure of Western European refineries has not kept pace with the changes in regional product demand trends, as gasoline demand has fallen and the demand for middle distillates, mainly high quality on-road diesel fuel, has grown at a robust rate.

The large volumes of long residue, vacuum gas oil, and middle distillate supplies from Russian refineries have comprised a key supply component for Western Europe's growing appetite for high-quality distillates, allowing European refiners to defer refinery investments to increase middle-distillate production.

The regional surplus production of gasoline has been minimized by substituting straight-run residue and VGO for crude oil in conversion refineries. For this reason, the potential reduction in supplies of Russian secondary feedstocks has ramifications well beyond Russia's borders.

The author

William J. Sanderson is president and CEO of Purvin & Gertz Inc. He started his career with the UOP Process Division, a refinery technology licensor. He later joined Champlin Petroleum Co. (now Valero Energy Corp.) where he held a variety of management positions including manager of process engineering and manager of economics and planning. After joining Purvin & Gertz in 1988, Sanderson conducted consulting assignments for West Coast and Asia Pacific clients. He later moved to the London office and directed the firm's consulting activities in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. He transferred to Houston and was elected to his current position in 2000. Sanderson holds a BS in chemical engineering from Montana State University.