Through dynamic portfolio management, integrated oil and gas companies can identify strategic adjustments with the potential to greatly improve asset values. Oil companies have frequently relied on two key criteria to enhance and sustain value in their portfolios: operational effectiveness, with the intent of driving sustainable performance improvements, and financial discipline, with the intent of closely managing free cash flow. Operational effectiveness has yielded increased levels of operating reliability, improved safety and environmental performance, and lower operating costs. For a number of oil companies, financial discipline is a hallmark that sets them apart from their peers in the stock markets, which place a premium on superior returns on capital employed.

However, for most oil companies, these capabilities do not provide the differentiation needed for delivering superior competitive performance. Instead they are only prerequisites to a value-creation strategy. For superior value creation, an oil company also needs to explicitly manage its portfolio of businesses, assets, and market positions, not only in the upstream but also across the entire company.

This article examines value enhancement in the downstream sector, specifically how to establish a framework for extracting additional downstream value by incorporating dynamic portfolio management into the strategy. The article concludes with a hypothetical case study that demonstrates the resulting benefits from this proactive approach.

Identifying a framework

To manage a portfolio in a proactive manner that allows for countercyclical adjustments, short-term and long-term objectives need to be aligned across the time horizons. In addition, management needs to understand the risk-value profile of the company's existing portfolio, as well as the sources of value and risk and their interdependence. Lastly, the company will need to know the degree of feasibility for establishing and protecting favorable competitive positions.

Once these objectives have been established, they should be incorporated into a framework for ongoing identification and evaluation of portfolio adjustments. In addition, the framework should include an appropriate strategy for each business unit. Almost all business units have the desire to grow, but this is not realistic. Resources must be properly allocated in conjunction with the strategic priorities of the units. This is often a contentious process and not necessarily executed in a logical fashion or in a manner entirely consistent with the strategy. In addition, management must select performance targets for each of the business units to ensure optimal performance levels.

The multiple dimensions of portfolio management must also be incorporated into the framework. Management must decide if the company should be in businesses or markets only where it can be No. 1 or No. 2—especially since some niche positions, even in the downstream oil sector, can be highly profitable. Also, the company must determine if its market capture will be built by expanding its presence within existing markets or by venturing into new markets. Finally, management must determine an appropriate balance for the domestic and international components of its portfolio. Different projects—as well as the countries where the projects exist—have different risks, but the risk associated with specific opportunities is not necessarily the same for all companies. Instead it is dependent on the respective capabilities.

Failure to consider these and other dimensions will result in an approach that is too narrow and tied too closely to the past.

Building the framework

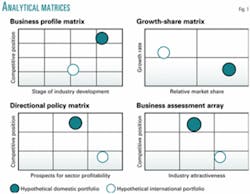

The employment of analytical matrices or schematics (i.e. simple models) to assess competitive scenarios and strengths and weaknesses can lead to misconceptions and improper portfolio-related decisions (Fig. 1). Simple models share a common set of critical weaknesses.

First, each of the frameworks implicitly assumes that the businesses are independent as the frameworks do not provide for any consideration of the synergies and dependencies between the business units. Second, equal weighting is given to the two main dimensions of the matrix (i.e. the X and Y axes), which fails to indicate whether having a strong competitive position or being in an attractive market is more important. Third, a single future competitive environment is assumed. In three of the models, the future is essentially assumed to be the same as the past, and all the models present a static view of the external environment, with no consideration for the actions and reactions of the competitors.

In addition, the frameworks assume the level of risk is the same across all of the businesses. What is more important, they do not provide any guidelines for establishing an optimal portfolio or optimal resource allocation. In effect, there is no explicit link between the frameworks and the strategy development process. As such, the results from the frameworks can be easily misapplied or, most likely, ignored.

Instead of relying on schematics, it would be much more useful if decision-makers had the ability to understand the market and competitive factors that are driving the current level of industry profitability and to assess what would have to happen to make the markets more or less attractive in the future, as well as the probability of such events taking place.

They also need to understand the relative competitive position and the underlying structural and operational factors along with the feasibility of improving the current position. Equally important is an assessment of how competitors view the industry and the external environment and their ability to react to changes, including strategic initiatives of other companies.

Only by employing more-sophisticated tools and concepts, such as game theory, scenario planning, real options, and system thinking, can this level of knowledge and understanding be developed. Integration of these concepts and tools makes a dynamic framework possible.

Within such a framework, potential future competitive environments are viewed as the result of the economic and structural drivers, the competitors' perceptions of the future, and the resulting actions and reactions to market changes and to each others' initiatives. It is within the context of the potential futures and the corresponding relative positions of the competitors that the portfolio alternatives need to be identified and evaluated.

Applying the framework

To apply the framework effectively, companies must define the aspirations, performance requirements, and boundaries of its strategy and provide the context for assessing potential portfolio alternatives.

First, managers need to agree on a long-term industry point of view—substantially longer than 5 years. The extended time horizon is valid for oil companies, given that the establishment of favorable structural positions requires a long-term perspective. Furthermore, there are significant barriers to reversing most portfolio-related decisions.

Next, managers must set performance targets from an internal and external perspective and establish the difference between these requirements and the performance implied by the current strategy and portfolio. The performance gap will then define the warranted level of change.

Managers also need to understand the basis for the competitive position at the corporate and regional levels. Companies should compare themselves against key competitors and within the context of each of the potential future external environments. The strategic and portfolio differences (regional and functional) should be identified and evaluated. Key structural and operating factors across each applicable element of the value chain should also be assessed (Fig. 2), as should intangible assets (relationships, reputation, specialty knowledge and experience, and intellectual property).

By pulling together all of the above aspects, a company can identify the differences in current and expected performance in relation to each key competitor and the underlying reasons for the difference. This practice will help managers establish key strategic and operating priorities.

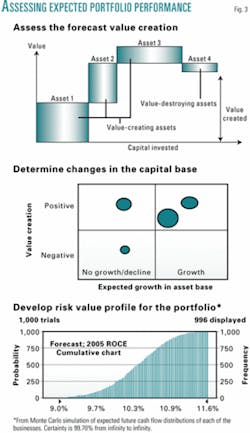

Finally, managers need to have a full understanding of the expected performance of the existing portfolio in the context of future external environments. This understanding involves assessment of the changes in the capital base associated with the current strategic plans and determination of which businesses are expected to create or destroy value (Fig. 3).

The overall risk-value profile for the existing portfolio can be created from the expected future cash-flow distributions for each of the businesses and the utilization of Monte Carlo simulation methods.

Case study

A simple case study based on a hypothetical integrated oil company illustrates how the framework can be used.

The performance expectations for the downstream portfolio differ as follows among the geographical regions:

Region 1 currently represents 45% of the downstream capital employed and has been traditionally the most profitable region as a result of the company's strong structural position. However, the market is poised for a significant downturn as hypermarkets are expected to gain substantial market share, and refining margins are expected to deteriorate with the convergence of fuel specifications, thus removing a structural barrier.

Region 2 represents 15% of the downstream capital employed and has been delivering less-than-adequate returns for several years, stemming from a difficult market and a relatively weak competitive position associated with limited scale in chosen markets. The region, however, has little downside risk, given its economic stability and retail margins that have been very low for several years and that should experience some recovery from expected closure of retail sites. Refinery margins should also get a boost as new environmental regulations will drive refinery closures.

Region 3 represents 20% of the downstream capital employed. Performance has declined as the region has gone through an economic downturn. The company's competitive situation has also declined. The region has been allocated limited capital funds in response to the low returns. The region, however, experienced high growth rates prior to the economic downturn and is expected to do so again once the economy rebounds.

Region 4 also represents 20% of the downstream capital employed. The company has focused on marketing in this region as national oil companies dominate the refining sector. The region has historically experienced economic instability; therefore, significant risk is associated with the cash flows from this region.

Based on these factors, we applied the suggested portfolio management framework to assess impacts on the company's value. The exercise consisted of numerous analyses. Among them, we developed portfolio alternatives by considering the competitive position and expected future market conditions. We assessed potential competitive actions and reactions through simulation and gaming exercises. We also developed margin and volatility forecasts for each of the potential future environments, a distribution of risk-adjusted cash flows making use of the current strategic plans and external forecasts, and a net-present-value (NPV) probability s-curve for each of the portfolio alternatives.

Portfolio alternative

Creation of the chosen portfolio alternative involves reducing the upstream weighting through divestiture of some mature fields. The downstream weighting increases to 35% from 27% because of the upstream divestitures in conjunction with downstream adjustments that include:

- Reducing the marketing presence in Region 1 through divestiture before the structural deterioration takes effect.

- Increasing the weighting in Region 2 through an acquisition that resolves the weak competitive position and also restructures two difficult markets.

- Strengthening the position and presence in the emerging market that is posed for improved economic conditions and thus strong demand growth in the future.

Exiting numerous markets in Region 4, where risk outweighs any potential upside.

Although hypothetical, the portfolio moves had a significant impact: The mean value of the NPV of expected future cash flows increased by 10%.

Benefits

Adopting the suggested portfolio-management approach offers a number of benefits. First, it would force managers to take a forward-looking perspective when assessing the portfolio. It also helps set strategic priorities through the identification of the relative future importance of key structural and operating factors, while also providing the basis for establishing the value associated with the flexibility to revise portfolio adjustments at a later time.

The framework and its associated quantitative analyses do not replace managerial judgment. They do, however, explicitly link portfolio management with strategy development, and short-term objectives with long-term objectives.

Both will support the consideration of proactive portfolio adjustments that would create substantially higher value than reactive adjustments.

The author

John Paisie is a senior director in PFC Energy's Downstream Consulting Practice, focusing on the development of corporate and operational strategies. He specializes in assisting clients to undertake strategic reviews and to implement major change initiatives. Paisie is a professional licensed engineer and has an MS in management from Purdue University.