Mexico faces challenges in deepwater operations

Managers of Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex), recognizing the importance of deepwater exploration and development to Mexico's hydrocarbon-producing future, acknowledge the need for capital and technology from abroad and are examining forms of strategic association with international operators. But some of the challenges facing Pemex require solutions before Mexican prospects in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico become major targets for foreign drilling investment.

The stakes are immense: the resource potential for another North Sea.

An important sign of changing Mexican attitudes toward the participation of outsiders in oil and gas operations—at least in deep water—came on Oct. 18. Speaking to a meeting of the Houston World Affairs Council, Federal Deputy Juan Fernando Perdomo said that in the preceding month more than 100 federal deputies and senators from all parties approved a list of 30 reforms that could be carried out in the remaining 2 years of the administration of President Vicente Fox. The 24th item on the list included a measure that would let Pemex, with congressional approval, enter into strategic associations with international companies for areas where Pemex lacked technology. One such area is deep water.

And the promotion on Nov. 1 of E&P Director Luis Ramírez Corzo to be the CEO of Pemex sent an unmistakable message: that the agenda of deepwater exploration and development is one that the Fox administration takes very seriously. Under Ramírez Corzo's leadership, Pemex has made unprecedented efforts to extend its knowledge of the geoscience, economics, and politics of deepwater development. Ramírez Corzo also has held extended discussions with major deepwater operators—including BP PLC, Royal Dutch/Shell Group, Unocal Corp., Total SA, and Statoil ASA, among others—about the concept of association contracts.

If Mexico is to accommodate the participation of foreign operators in deepwater E&P, the Congress must adjust several laws and regulations. If Congress moves slowly, Pemex—already working with non-Mexican drilling contractors and fully aware of the need to tap deepwater potential soon—may have to proceed alone.

Deepwater preparations

E&P managers at Pemex have been preparing for deepwater operations for a decade. In 1993 they prepared a 10-year mapping and exploration plan for the region and established seven subareas for study. But commitment became possible only in the Fox administration, during which E&P managers have formed a team and dedicated substantial resources to deepwater evaluation.

In February 2003 at its third, biennial upstream conference, Exitep, Pemex organized sessions around deepwater issues and heard presentations by companies with deepwater expertise. Since then, a senior Pemex geoscientist, Guillermo Pérez Cruz, based in Villahermosa, has been assigned responsibility for coordinating deepwater studies. The topic appeared high on the agenda of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists meeting in Cancún Oct. 24-27.

While the Mexican portion of the Perdido fold belt remains undrilled, in August Pemex's Luiz Ramírez Corzo told the Mexican and international media that a resource assessed at 54 billion boe exists beyond the Mexican continental shelf.

Pemex E&P defines "deep water" as exceeding 500 m. Its development plan for 2002-06 calls for the evaluation of the potential in deep water by means of at least 11 exploratory wells and the acquisition of some 23,000 sq km of 3D seismic data. One well, Nab-1, is currently being drilled in the Sureste (Southeast) basin in 670 m of water. With a proposed TD of 4,400 m, it targets Upper Jurassic to Upper Cretaceous strata analogous to productive formations in shallow water.

In June 2003 Pemex E&P sealed a 4-year contract with Diamond Offshore Drilling Inc. to provide three semisubmersibles able to drill in deep water. Pemex plans several other wells in about 700 m of water.

Meanwhile, international companies are in full discussions with Pemex about their respective operational and regulatory experiences, know-how, and requirements. The theme of deepwater development was part of a 2-day trade exposition Oct. 20-21 sponsored in Villahermosa by the British Chamber of Commerce. Ambassador Denise Holt told the audience that the UK government "is ready to help Mexico in whatever form is needed in order for Pemex to bring about strategic alliances to explore for and produce oil and gas in the deepwater areas of the Gulf of Mexico."

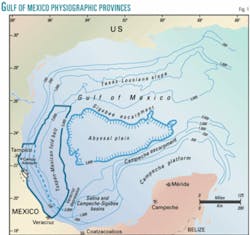

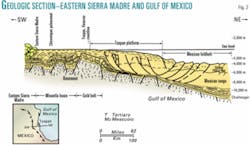

Early studies

In the executive summary of a 1993 internal report entitled "Present situation and outlook for oil exploration and production in the Gulf of Mexico," Pemex, drawing on published studies, provided an overview of its understanding of the plate-tectonic evolution of the region and identified seven areas for study: the Matamoras area, Tuxpan-Mexican fold belt, Veracruz Depression, Salina and Campeche-Sigsbee basins, Campeche Sound, Campeche Platform, and Campeche Escarpment. The most promising of the areas identified was the Mexican fold belt, which extends from the US border to the Veracruz Depression in 1,000-3,000 m of water (Fig. 1). The fold belt is located beyond the Tuxpan Platform, as is seen in a cross-sectional view (Fig. 2).

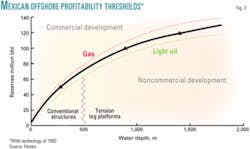

The report described each of these areas briefly, with accompanying maps and cross-sectional views. It included a curve showing economic feasibility of individual fields as a function of water depth and reserves, based on technology available at the time (Fig. 3). Overall, it estimated the cost of deepwater oil recovery at $7.50/boe for the gulf, compared with an estimated $11.50/ boe for offshore Norway. Total potential resources were estimated in the range of 10-30 billion boe.

During the Fox administration Pemex's success rate for new fields has not met expectations. In gas, what in 1999 was called the Strategic Gas Program has practically, if not formally, disappeared. In a mid-January 2002 briefing of journalists, Pemex managers described a newly discovered field named Lankahuasa as of a type "found only once every 20 years." Yet Lanka- huasa received almost no publicity until the 2004 AAPG conference.

Undaunted, Pemex upstream leaders have affirmed their intention to increase oil production to 4 million b/d by 2006—too soon for whatever production might result from deep water. Absent a new round of shallow-water discoveries, Mexican oil production will not surpass the current ceiling of 3.4 million b/d and will decline in parallel with the decline of Cantarell field. Deepwater resource development is a commercial imperative for Pemex and a fiscal imperative for the Mexican government (OGJ, Mar. 1, 1993, p. 43).

Pemex in deep water

Pemex E&P is the largest offshore oil producer in the world; nevertheless, upwards of 90% of Pemex production is in fields in 100 m or less of water. Pemex upstream managers harbor no illusions that a do-it-yourself approach to deepwater development is realistic.

Work in more than 200 m of water has to date not fulfilled the company's hopes. Pemex made a discovery in the Ayín-1 well in the 1990s but has conducted no further drilling in the area. It is rumored to have drilled at least one exploratory well in deep water with a contracted rig but to have found no commercial hydrocarbon deposits.

In late June Mexican Sen. Demetro Sodi told an energy trade delegation led by Texas Railroad Commissioner Charles Matthews that the Senate was considering a bill to allow Pemex to enter into associations with private companies for plays "that were difficult or beyond Pemex's technological capabilities." Since then, the only public document mentioning strategic associations for deepwater development has been the one included in the list of 30 reforms disclosed in Houston.

A private indication of progress in this area came in an invitation-only meeting Sept. 28 during the Society of Petroleum Engineers annual convention in Houston. There, Pemex's Ramírez Corzo encouraged about 30 industry executives to believe in the existence of substantial hydrocarbon deposits in deep water off Mexico and said progress was being made in finding a mechanism for strategic associations between Pemex and private companies.

Government challenges

One falsely perceived hurdle to the formation of strategic associations is the Mexican Constitution. For years, supporters and opponents of private participation in Mexico's upstream oil industry have argued that Articles 27 and 28 of the Constitution need to be respected or changed. The articles say that hydrocarbons belong to the nation, that only the nation may exploit them, and that the oil industry has strategic importance for Mexico.

Industry observers point out that state ownership of hydrocarbon resources is standard worldwide outside the US. It is therefore only the so-called secondary laws and their regulations that need changing, not in Constitution.

Another challenge is the transformation of Pemex, which is not so much a professional oil company as it is a government-administered oil supply agency and the source of a third of the federal government's budget. A dozen outside government agencies plus the energy ministry have involvement in the day-to-day operations as well as in the strategic planning of the company. The most influential of them is the finance ministry.

Few international oil companies would want to make a joint venture with Pemex and an unlisted number of state agencies and ministries, each with a scope of authority that is, at best, insufficiently documented in the public domain. For example, the Office of the President of Mexico—not the CEO of Pemex—has the authority to name and replace corporate vice-presidents of the operating units, as well as selected lower-level officials such as the director of public relations. There is no public accountability for such decisions, and Pemex's board of directors has no independent authority.

For a decade, Pemex executives have, in bureaucratic terms, expressed the need to allow the company to work as a real, state-owned oil company. The transformation would require a change in laws governing state-owned companies, foreign investment, and government procurement. Changes also would be needed in implementing regulations. In the view of many, a new independent upstream regulatory authority is urgently needed—in addition to the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), which is dedicated to midstream issues relating to gas franchises and permits but without the staff or desire to take on upstream issues. One of the benefits of an upstream regulator would be that Congress could delegate oversight authority that, in the Fox administration, it has arrogated to itself in matters relating to upstream energy policy.

Congress would have to define its own role in a strictly oversight capacity, not over specific contracts but over law, its compliance, and the political culture and rhetoric in which oil matters are discussed. To implement the idea that deepwater, strategic associations need approval of Congress (as proposed in the list of 30 reforms) would be to continue an antimarket tradition of oil-sector management.

Prospective operators have proposed a series of enhancements to the bidding procedures. A single sentence of bidder requirements in a public tender for deepwater operations would reduce the list of prospective bidders to a half-dozen companies. The procurement process applicable to Pemex's major projects should be changed to a best-value procurement methodology, one which allows the sponsor of a tender to take into account qualities of the plan, team, schedule, safety program, and other factors (see related story, p. 22).

Needs of IOCs

The Mexican government must find a clear and straightforward way to respond to the basic requirements of international oil companies (IOCs) for deepwater operations in Mexico. These requirements include the posting of discoveries to the reserves account of the operator, a compensation mechanism that responds to market conditions, an equitable fiscal regime, and the full support of the law and political culture.

Although Pemex publishes Mexico's oil and gas reserves statistics, it is not the owner of reserves, which by law and constitution belong to the state. In the development of a transboundary resource, the matter of "whose oil?" needs special attention, if only from a fiscal perspective. Worldwide, IOCs operate on the basis that the host company owns oil reserves. But this fact does not restrict the companies from being credited with the discovery of new reserves. That an IOC posts its discoveries on its account does not subtract these volumes from Mexico's account: the reserves on the Mexican side of the border still belong to Mexico.

Prospective operators believe that the mechanism for unit cost recovery as used in the multiple service contracts (MSCs) that have been awarded for gas projects in the Burgos basin is wholly inappropriate for deepwater operations. Prospective strategic associates must receive some market-based compensation in return for the investment of their financial, technological, human, and intellectual capital.

The fiscal regime must leave a competitive share of "profit oil" or its equivalent on the table for the IOCs, where "competitive" is what is found worldwide in comparable circumstances. From the perspective of the host government, payments to the IOCs are part of development costs.

Requiring the "full support of the law" in a country in which the expression "sí pero no (yes but no)" has wide currency will be difficult but certainly not impossible. Strong forces in the Congress oppose the MSCs, not for the details of the contract but for the principle that international oil companies have any role in Mexico. The Fox administration has been stingy in its investment of political capital to change public perceptions on this point.

Support for this change in perspective in Mexican political society toward the IOCs would be gained by the creation of an upstream regulatory authority, perhaps modeled on that of Norway. The energy ministry in Mexico has studied this issue—if not to death, at least to the exhaustion of the patience of many who would ask its committee to come out with a proposal for a regulatory agency that would stand between Pemex and the IOCs.

The greatest challenge of all, however, will be in the definition of the selection process by which Pemex's strategic partners are chosen. The method must allow for public oversight, while, at the same time, avoiding the costly simplifications and distortions inherent in traditional public tenders.

Deepwater priority

While the ballpark figure of a 30-billion bbl potential may have been around for a decade, only during in the first 4 years of the Fox administration have sustained efforts and budgets been committed to this frontier. What was little more than a guess in 1993 has been established as a plausible estimate with a decade of additional geoscience. Know-how also has moved forward, and clastic deepwater reservoirs have a 50-60% recovery rate with today's technology.

It is clear that Pemex needs the financing, technology and expertise that the leading deepwater oil companies offer. But it and the government must answer a range of questions: How to select specific partners? Following which criteria? Who decides? These are questions that can be answered only once the table has been set for invited guests.

It is doubtful that Pemex will find deepwater drilling contractors willing to work for an inexperienced operator in a production mode; the risks are too high for the contractor's image worldwide. Hence, the do-it-yourself model of commercial development is impracticable.

No "association" agreement will be attractive to a qualified oil company unless—and in addition to commercial issues like reserves recognition and market-based compensation—its political and legal viability is assured. None of this will be easy.

Given the historical and ideological baggage that Pemex is forced to carry, the commercial tables of prospective strategic associations are slightly tilted toward those deepwater-qualified companies that are or have been wholly or partly state-owned. Companies in this category include Statoil, BP, and Total. Two companies still owned by governments, Petróleo Brasileiro SA and Statoil, are alike in that their governments developed upstream regulatory authorities of the type needed in Mexico. Perhaps for this reason, Mexican executive and legislative officials have visited Brazil and Norway repeatedly during the Fox administration.

While support for reforms that include attention to deep water is important, it comes from 100 members of a Congress that has 500 members in its lower house and 128 in its Senate. Having 100 supporters is enough to get press attention but not enough to change law, policy, or political culture.

Still, the deepwater future of Pemex is clear and inevitable—it's only the present moment that is confusing. The confusion would be substantially reduced if the Fox administration would commit itself outright to a deepwater agenda for Pemex or, at the very least, push for an upstream regulator and a best-value procurement system for Pemex and the CRE. Passing the torch to the next administration on these vital issues will be judged as a failure of leadership.

The author

George Baker is a petroleum analyst and director of Mexico Energy Intelligence, an industry newsletter service based in Houston. He is the author of Mexico's Petroleum Sector (PennWell, 1984), articles listed at www.energia.com, and numerous articles since 1981 for Oil & Gas Journal and its affiliate Spanish-language magazine, Oil & Gas Journal Latinoamerica.