Middle East feedstock advantages continue to support surge in petchem capacity

Feedstock advantages in the Middle East are fueling a powerful and continuing upsurge in ethane-propane cracking for petrochemicals.

Petrochemical feedstock costs in energy-importing countries such as the US and Japan are a function of the prevailing price of energy. Middle East feedstock supplies, on the other hand, are more typically priced on long term, low-price contracts.

These contracts, and the ethylene cash cost advantage they provide, are leading to national development and progressive petrochemical expansion in energy-exporting nations.

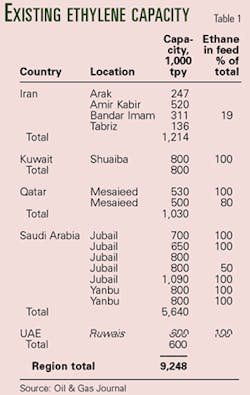

Existing ethylene industry

Table 1 shows existing ethylene cracking capacity in the Middle East. The majority of that capacity, except for Iran, is devoted to ethane cracking.

With more than 9 million tonne/year (tpy) of ethylene capacity, the Middle East is already established as a key world petrochemical hub.

Middle East petrochemical developments tend to use ethane and LPG feedstocks. Key Middle East countries such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and UAE have large gas industries and significant LPG exports. These industries have been the source for most ethylene feedstocks.

Naphtha has been relatively neglected in those countries but is emphasized in Iran, which produces relatively little LPG and has a less-developed gas industry. Consequently, existing ethylene production plants in Iran are mostly naphtha-based.

Using the lightest feedstocks is logical in the Middle East because heavier feedstocks such as naphtha have a greater market value and are easier to ship. The ethane in natural gas only has a fuel value, which is naturally low in the resource-rich Middle East.

Natural gas development

The past few years have seen a surge in natural gas developments in key Middle East countries; this surge will continue in the medium term.

Qatar has focused on LNG and gas projects. Saudi Arabia is more interested in expanding gas production to fuel its domestic industry and tends to see LNG or gas exports as competition for higher-valued oil. Iran seeks to monetize South Pars resources using a combination of many projects oriented towards LNG, domestic gas, GTL, and other areas.

Saudi Arabia's gas program has evolved considerably since its inception in the 1970s. Originally, Saudi Arabia sought to eliminate the flaring of associated gas in order to free up more oil for export.

The program was successful. By the mid-1980s, gas consumption had become so important that associated gas was insufficient to meet demand and nonassociated gas developments were required.

Saudi Arabia has recently expanded gas processing to recover more ethane for petrochemicals to achieve more added value compared to consuming ethane as fuel. Now Saudi Arabia is seeking more nonassociated gas resources, principally in the Empty Quarter with participation of private capital.

Iran's gas history is different. Whereas Saudi Arabia needed to find and develop new sources of nonassociated gas, Iran is blessed with the South Pars field.

The challenge with South Pars is not discovery but development. The pace of South Pars developments has been slower than proposed, but ultimately the field will provide enormous new volumes of ethane and LPG for petrochemical consumption.

Qatar's huge North field has been more successfully developed than South Pars. Qatar has emphasized North field development as an engine for national economic development. That program includes LNG development and expanded petrochemicals manufacturing.

Each of these countries initially focused on pipeline or LNG gas supply; they now seek to use natural gas production for low-cost petrochemical feedstocks. Gas produced in the Middle East is relatively wet and lends itself to economic feedstock extraction.

Capitalizing on the feedstock cost advantage, all three countries seek national development and a greater share of the international petrochemicals markets.

LPG

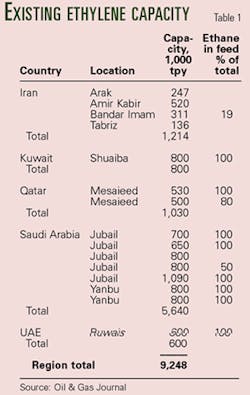

As with natural gas, Middle East countries are producing growing volumes of LPG (Fig. 1). Historically, LPG has been0 mostly exported. These materials are also attractive as petrochemical feedstocks, especially for the production of propylene and its derivatives, or methyl tertiary butyl ether.

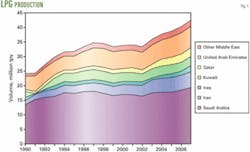

Middle East petrochemical developments consume ethane and the LPG components propane and butane. Petrochemical feedstock uses for those materials include olefins cracking and MTBE manufacturing.

Fig. 2 shows growth in Middle East LPG demand. Of the 11 million tpy of additional consumption since 1990, about 90% is devoted to petrochemical feedstocks.

Middle East countries generally find that exporting value-added petrochemicals is more attractive than exporting LPG. Although the region has produced increasing volumes of LPG, export growth has lagged and fallen at times.

There is a possible decline in LPG volumes during the next decade. The rise of Middle East petrochemical development, therefore, has a potential dark side for Asian LPG consumers who might need to look further afield to find sufficient LPG for residential and commercial consumption.

Some gas developments that provide ethane-propane feedstocks in the Middle East also tend to produce condensate that is supplementing naphtha availabilities in the Asian market. Middle East countries have been selling condensate to Asian consumers or splitting the material domestically.

Key production increases have occurred in Qatar due to LNG expansions, Saudi Arabia due to domestic gas developments, and Iran due to South Pars projects.

Middle East naphtha production is also rising. Middle East refiners are expanding production capacity. Part of the push for more Middle East refining has been the region's requirements for gasoline.

Naphtha converted to gasoline reduces the amount of naphtha available for petrochemical production. Other refineries and condensate splitters in the Middle East, however, are producing more naphtha, which contributes far more to petrochemical feedstocks in Asia than in the Middle East.

Although ethane, LPG, condensate, and naphtha all are readily available in the Middle East, we expect a continued focus on ethane, as the material has the lowest alternative value in Middle East markets.

Most Middle East countries have large surpluses of relatively wet natural gas. Using ethane as feedstock tends to increase the volume of gas produced, maximizes exports, and adds to the value of the available resources.

Feedstock price advantage

Shifts in the worldwide petrochemical feedstock cost relationships are benefiting Middle East petrochemical projects.

Most international petrochemical producers pay market prices for feedstocks. These producers are consequently subject to squeezed margins depending on the price relationships between feedstocks and petrochemical derivatives.

Middle East ethane consumers tend to receive feedstocks at far lower prices than many international petrochemical producers. These prices tend to be fixed or far less market-sensitive than naphtha or LPG prices.

Key petrochemical feedstocks are ethane, LPG, and naphtha. Ethane is not priced internationally because there is no liquid global market for it. Ethane is not widely shipped internationally and is usually consumed near the point of production.

Ethane prices in the Middle East can be set to achieve national economic objectives. The cost of ethane to Middle East producing countries depends on the value of natural gas. Middle East industrial consumers enjoy relatively low and unchanging natural gas prices; therefore, the value of ethane extracted from gas also is low. That has provided Middle East ethane consumers with an advantage in recent years—feedstock costs that are stable and low.

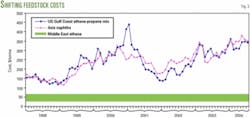

Fig. 3 shows prices for US ethane, Asian naphtha, and Middle East ethane during the past 5 years. The price of Middle East ethane is less transparent than other prices but varies across national boundaries; consequently, Fig. 3 shows these prices as a constant band.

Prices of Asian naphtha are indirectly related to the crude oil from which it is derived; they have risen since the crude oil price trough of 1998-99.

US ethane prices are a function of North American natural gas prices. In the US, ethane is extracted from natural gas. Prevailing ethane prices typically reflect the heating value of extracted ethane plus a margin sufficient to cover plant operating costs and a profit element.

Since 2000, the feedstock price advantage available to Middle East petrochemical producers vs. competitors in North America or Asia has expanded. That feedstock cost advantage overwhelms the extra cost of shipping petrochemicals to consuming markets and fuels the continued expansion of the Middle East industry.

In the North American market, ethane and ethane-propane mix have been the predominant feedstocks for many years. Although other feedstocks such as naphtha are used, low natural gas prices through the 1980s and most of the 1990s created the opportunity for low-priced ethane and ethane-propane mix. North American producers capitalized on that feedstock cost opportunity to rapidly expand capacity.

US natural gas surpluses have faded because gas developments have not kept pace with gas demand. The US has consequently entered a period of relatively high natural gas prices and is quickly developing LNG import projects to mitigate the possibility of gas shortfalls.

Canada—the source of about 20% of US natural gas supply—similarly has few prospects for export expansions; developers of new energy-consuming projects, such as oil sands projects, must be concerned about future energy supply and pricing.

North American gas shortfalls have translated into a more-expensive ethane and ethane-propane mix while Middle East producers' feedstock costs have remained essentially flat. That factor has contributed to a shift in the competitive balance in favor of Middle East producers.

Similarly, feedstock-cost relationships for Asia vs. the Middle East have shifted in favor of the Middle East producers.

In most Asian countries, the key petrochemical feedstock is naphtha. In Asia, LPG typically is too high priced to be cost competitive with naphtha for petrochemicals. Most Asia-Pacific locations have insufficient low-priced gas to develop an ethane-based petrochemicals business.

Naphtha prices, like all major refined products, are highly correlated to crude oil prices. Since 1999, OPEC's price-band policy and a series of serendipitous supply-and-demand side events have led to a considerable crude oil price increase vs. 1990s prices. Rising crude oil prices have also led to higher naphtha prices.

Although the basic underlying market reasons are different, the outcome for Asia-Pacific petrochemical producers has been the same as for those in North America. Both regions have lost competitive ground vs. the Middle East.

The Middle East's feedstock cost advantage translates into lower-cost ethylene. The ethylene cash cost measures the relative competitiveness of ethylene from different sources.

The cash cost advantage of Middle East ethylene was $100-160/tonne in 1998; more recently the cost advantage has been $200-330/tonne due to market-related feedstock cost increases outside the Middle East.

The Middle East has more feedstock potential than is currently used to manufacture petrochemicals.

Saudi Arabia has approved feedstock allocations for eight additional ethylene crackers and seeks to double its already impressive petrochemical capacity in the next 5 years. Until this capacity is installed, the potential added value of petrochemicals will be lost to Saudi Arabia.

Adopting a fixed-feedstock price strategy has advantages for stepping up petrochemical development. Prices throughout the Middle East are generally quite low, which provides for large margins. The policy of holding those prices constant despite rising world prices means that the margin risk associated with Middle East projects is far lower than that of developments elsewhere.

Petrochemical projects in consuming countries such as China must more carefully evaluate margin risk. Although investors in many Chinese petrochemical plants have been able to find suitable projects with rewards that are commensurate to perceived risk, margin risk is more worrisome in China than in the Middle East. Reduced risk leads to faster development than would otherwise occur.

Outlook

Any list of Middle East petrochemical projects would be incomplete currently because there are more opportunities triggered by feedstock availability and favorable cost. Also, the perception of improvements in the petrochemical cycle and expansive economic conditions around the world create interest.

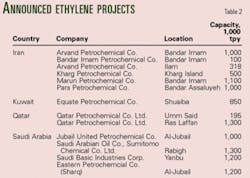

Middle East countries realize that more rapid and profitable petrochemical investments are possible when private-sector investors are involved. This combination of factors has led to existing Middle East projects (Table 2). Projects will be extended and expanded as conditions allow.

The speed of gas developments such as South Pars and the political uncertainties associated with the Middle East in general are constraining the pace of Middle Eastern petrochemical developments.

Some Middle East countries have some difficulty reconciling the goal of accessing external private capital with the traditional roles of the state and state enterprise. Countries that most rapidly find a suitable common ground with external investors, including the means to repay for resource development, will enjoy the earliest success in petrochemical development.

Ethane and ethane-propane mix availability is a function of gas development. Some gas development projects have been delayed due to contractual, financial, or political factors. These delays can cascade into petrochemicals slowing the entire development process.

Recent tensions in the Middle East also tend to delay developments. Groups that seek to undermine existing governments have found foreign workers in some countries to be satisfactory targets for political statements. Some of the goals of these groups are economic: they seek to prevent economic progress and development.

These actions result in deterring foreign workers from visiting the Middle East and create the perception of additional risk for investors. These difficulties will add to project delays unless a satisfactory resolution is found in the short term.

Middle East countries are still at a relatively early point in the petrochemical industry's development. South Pars and North field developments will proceed in the medium to long term and the ultimate scale of gas and petrochemical feedstocks production will be a multiple of what is produced today. As impressive as the recent gains have been, opportunities for low-cost feedstocks are far from exhausted.

Middle East countries are likely to seek continued private investment in the petrochemical sector to achieve the national goals of expanding value-added industrial development, capitalizing on available comparative advantages, improving industrial efficiency, accessing cutting-edge technology, and penetrating international markets that are familiar to the existing petrochemical firms.

The opportunities to produce low-cost petrochemicals for world markets will continue to attract foreign private-sector investors. These firms seek a competitive advantage and an enviable position on the cost curve with every new venture in the Middle East.

Middle East nations and their domestic and foreign private sector partners stand to profit from continuing petrochemical development.

The authors

John H. Vautrain is vice-president and director for Purvin & Gertz Inc., Singapore. Before joining Purvin & Gertz in 1981, he worked for Phillips Petroleum Co. and Union Carbide Corp. Vautrain was manager of Purvin & Gertz's Long Beach, Calif., office 1987-2000. Elected director in 1997, he has been based in Singapore since 2000. His Asian consulting activities include crude oil marketing, petroleum refining, LPG, natural gas, and LNG. Vautrain holds a BS in chemistry from the University of Texas and an MS in chemical engineering from the University of Utah. He is a member of the International Association for Energy Economics, SPE, and AIChE.

Kurt A. Barrow is a principal with Purvin & Gertz Inc., Singapore. Before joining Purvin & Gertz in 1997, he worked for ExxonMobil Corp. in its Baytown, Tex., refinery. In 2001, Barrow transferred to the Singapore office. He has expertise in refining, marketing, crude oil, LPG, and gas-related topics. Barrow holds a BS in mechanical engineering from Kansas State University and an MBA from the University of Houston. He is a member of ASME.