High oil prices not squeezing economic growth—yet

Conventional wisdom states that high oil prices lead to lower economic growth, cause inflation, and increase unemployment.

The US recessions of the 1970s, 1991, and 2001 were all associated with high oil prices, as shown in Fig. 1. The chart plots real oil prices vs. US real economic growth from the first quarter of 1973 to the second quarter of 2004.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, Fig. 1 indicates that the recent increase in oil prices has not affected economic growth in the US. The same conclusion applies to most countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and several states in Asia. Does the current situation contradict the conventional wisdom? Why is the current situation different from that of the 1970s? This article investigates these issues and answers these questions.

Oil-economy relationship

The relationship between oil prices and economic growth is difficult to understand. The nature of this relationship is murky at best, even in the academic literature.

Although data indicate that economic growth turned negative in the initial periods of oil price increases in 1973-74, 1980, 1982, and 1991, the economy grew at high rates even under high oil prices, i.e., during 1976-78 and 1999-2000.

While historical data show an inverse relationship between high oil prices and economic growth in the industrial countries, it is unclear at what levels or ranges oil prices start to affect economic growth and how. It is also unclear if a causality relationship exists or if it is a mere association. Even if a causality relationship exists, it is unclear why it exists in some countries and does not exist in others. Given the appropriate lag, it is unclear if the causality is in one direction or bidirectional, and why it is in one direction in some countries and bidirectional in others.

This article does not intend to focus on this "controversy" of causality and association. Rather, it investigates the applicability of the conventional wisdom to recent periods of high oil prices and economic recovery. It explains the factors that prevented oil prices from affecting economic growth in recent months.

Economic growth unaffected

Experts who warn that the recent increase in oil prices will slow economic growth, increase inflation, and reduce employment base their opinions on the results of numerous studies that focus on the experience of high oil prices in the 1970s and their aftermath.

While those experts focus on the similarities between the current situation and that of the 1970s, they ignore several significant differences. The recent increase in oil prices is different from all the price increases in the past, including that of 1990-91.

These differences play an important role in explaining how the impact of the recent increase in oil prices on economic growth is different from that of the past.1 These differences indicate that conventional wisdom is still correct—but under certain conditions. These conditions include rising interest rates, decreasing government spending, decreasing military expenditures, and semifixed exchange rates.

Since these conditions do not currently exist, conventional wisdom does not apply. The past 2 years are the only period in OECD history when oil prices, economic growth, government expenditures, and military spending all have increased at a time when interest rates and the value of the dollar have continued to decrease. In addition, OECD economies started from rock bottom after the terrorist attacks on the US on Sept. 11, 2001, which makes it impossible for high oil prices to reverse the upward trend in economic growth.

The depreciation of the dollar limits the effect of higher oil prices to the US. A combination of factors, including low interest rates and increased government spending, helped the US mitigate any negative impact that high oil prices might have on the economy. The following section will examine these factors more closely.

Dollar depreciation

Conventional wisdom states that high oil prices hinder economic growth in the industrial countries. This assumption is true if exchange rates are fixed or stay relatively the same. Under these conditions, all countries suffer proportionally from the increase in oil prices.

If exchange rates vary drastically, higher oil prices will not affect econo- mies with nondollar-appreciated currencies. Current high oil prices will not affect the economies of Europe and Japan as much as they did in the 1970s. Oil is priced in US dollars. Current oil prices are high only in dollar terms, not in euro or yen terms. The depreciation of the dollar against the euro by about 40% and by about 13% against the yen in the last 2 years has mitigated the effect of higher oil prices on the European and Japanese economies, despite the fact that they are more dependent on foreign oil imports than the US.

Even by historical standards, nominal oil prices in Europe and Japan are relatively low, while they recently hit record highs in the US. In England, for instance, recent oil prices in pounds sterling are lower than England's oil prices in 2000, and they are even much lower than oil prices that prevailed during 1980-85. In Japan, current oil prices in yen are similar to the oil prices in 1976, and lower than oil prices during 1979-85 and in 2000, as shown in Fig. 2, which shows oil prices in US dollars and Japanese yen between 1973 and May 2004.

Fig. 3 shows oil prices in US dollars and euros. The chart illustrates that, despite the fact that nominal oil prices denominated in US dollars almost reached records, Europeans paid about 10 euros less for oil in recent months than what they paid in summer 2000. Oil prices in Europe are still low even by historical standards. There is no reason to believe that the recent runup in oil prices will have an impact on European economies. The depreciation of the dollar has limited the impact of high oil prices to the US, but, as we will see next, several factors prevented such high prices from slowing the recovery of the US economy.

Government spending jump

Conventional wisdom, based on the experience of the 1970s, states that high oil prices hamper economic growth.

This conventional wisdom is correct if high oil prices are associated with a decrease in government expenditures. Unlike the past, the recent increase in oil prices was associated with a significant increase in government expenditures in OECD countries, especially on defense and security. The war on terrorism and the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq have continuously increased defense and security expenditures. It is well-known in the literature that increases in government expenditures increase economic growth. This growth may overcome the contractionary effect of high oil prices.

The recent period of increasing oil prices has two distinctive features. First, it is the only period in history when government expenditures have increased substantially as oil prices are rising. Therefore, we cannot draw parallels with the 1970s when government expenditures decreased. Second, this is the only time in the last 30 years when government expenditures increased substantially for this long.

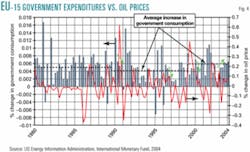

Fig. 4 plots percentage change in real oil prices vs. percentage change in government consumption expenditures in the 15 countries of the European Union (EU 15). The average increase in government consumption expenditures in the 1990s was around 0.4%/year. Since 2000, the average increase has grown to 0.6%/year. The chart shows that the recent period is the only period in the last 24 years when government expenditures in those 15 countries have increased constantly.

In the US, the recent period of high oil prices witnessed unprecedented increases in government expenditures, in both duration and size. Government expenditures have been steadily increasing in the last 15 quarters. On average, US government expenditures have been increasing at 1.66%/quarter in the last 3 decades. Since 2000, this average increased significantly to 5.45%, after declining at a rate of 0.8% in the 1990s. This average is even higher than the 1980s average, when the US budget deficit increased to historic levels, and much higher than the 0.06% average of the 1970s, when oil prices were rising.

To put this in perspective, the ratio of percentage change in real government expenditures to the percentage change in real oil prices was 0.67 in the 1970s, which indicates that the percentage increase in oil prices was higher than the percentage increase in government expenditures. The ratio declined to –356 in the 1980s as oil prices decreased and government expenditures increased. With slower growth in government expenditures in the 1990s to reduce the budget deficit, the ratio increased to –80. Since 2000, the ratio has averaged 182, a record high. This ratio indicates that the percentage change in government expenditures is 182 times higher than the percentage change in oil prices. With this massive stimulus, the recent increase in oil prices had a limited effect on the economy.

The period from 2002 to the present is the only period in history when government expenditures constantly increased as oil prices increased. When oil prices increased in late 1973, government expenditures were decreasing. Government expenditures decreased by more than 10% in third quarter 1973, just before the October oil embargo of that year. Government expenditures increased in 3 quarters in 1974 and in only 1 quarter in 1975. They decreased in all other quarters during that early period of oil price spikes.

During the increase in oil prices in 1979-80, government expenditures increased in 5 quarters out of 8. In 1990-91, despite Gulf War I, government expenditures increased in 3 quarters and decreased in 5 quarters. In 1996, government expenditures initially increased, but they decreased by more than 6% as oil prices increased during the summer of that year. During 1999-2000, oil prices increased significantly, while government expenditures increased in only 4 quarters out of 8.

The previous data of frequent ups and downs in US government expenditures highlight the significance of the increases in government expenditures in 15 consecutive quarters during the most recent period of increasing oil prices.

Role of low interest rates

Economists squabble over the impact of monetary polices on economic growth.

Regardless, the inverse link between interest rates and economic growth, under special circumstances, is well-established in the economic literature. Under certain circumstances, increasing the money supply and lowering interest rates stimulate economic growth. Such an increase may counter the impact of contractionary events such as an increase in oil prices.

Unlike any other period in history, the recent period is the only period when oil prices increased and money supply and interest rates were at historic levels. Nominal interest rates reached their lowest levels in 42 years, and real interest rates may have reached zero. None of the past episodes of higher oil prices witnessed a decrease in interest rates, let alone record lows. Fig. 5 plots US Discount and Federal Fund rates against oil prices. The chart illustrates that interest rates increased when oil prices increased in 1973, 1979, 1980, 1988, 1994, and 1999. It also shows that interest rates have fallen in the last 2 years when oil prices were increasing.

The conclusions of the 1970s about the inverse relationship between high oil prices and economic growth may not apply to recent events. Conventional wisdom is based on the experience of the 1970s, when high oil prices were associated with high interest rates. Therefore, conventional wisdom does not apply to the recent periods when interest rates decreased and oil prices increased simultaneously.

Real income-real oil price ratio

Conventional wisdom states that high oil prices stall economic growth as they did in the 1970s.

This conventional wisdom is correct if oil prices increase while income stays constant or declines. Real per capita income has increased at a higher rate than have oil prices, which makes the percentage of income spent on oil less than in earlier periods and increases Americans' buying power.

This "income effect" explains why Americans have not changed their behavior as oil and gasoline prices have increased in recent months. Real per capita income has increased consistently in the last 30 years, while real oil and gasoline prices relatively have decreased, as shown in Fig. 6. The chart shows real per capita income and real oil prices and their linear trends from 1973 to 2004.

Another way to illustrate this conclusion is to calculate the real income-real oil price ratio, i.e., how many barrels of oil an American can buy in a specific year. While the average was around 500 bbl during 1974-86, it doubled to 1,000 bbl during 1987-2003. With the recent sharp increase in oil prices, the average stands at more than 800 bbl, an increase of more than 60% over the buying power of the 1970s.

Conventional wisdom does not apply in this case: Higher oil prices at their level totay will not affect economic growth. The income effect is large enough to compensate for any negative effect of high oil prices.

Gradual increase in oil prices

Conventional wisdom states that higher oil prices negatively affect economic growth. This is true if the magnitude of the increase is considerable: Prices increase suddenly and significantly, as oil prices did in the 1970s after the October 1973 oil embargo, as well as they did after the Iranian revolution of 1979 and the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990.

Unlike the sudden and sharp increase in 1973, 1979, and 1990, oil prices have been increasing gradually since 2002. Such gradual increases have mitigated the effect of high oil prices on OECD economies. Within about 4 months, from October 1973 to February 1974, oil prices increased by fourfold. In less than a year, from March 1979 to February 1980, prices doubled. By March 1981, prices increased again by more than 20%. Even as the US prepared to invade Iraq, it took oil prices just 16 months to double before the war started.

From February 2003 to February 2004, oil prices stayed virtually the same. In the most recent runup, oil prices have increased by only 32% in the past 4 months. For a shock to take place and affect economic growth, the increase has to be sudden, large, and within a very short time. Therefore, conventional wisdom does not apply to recent periods of high oil prices. Conventional wisdom applies to situations where the magnitude of higher oil prices is very significant. The low magnitude of recent increase in oil prices made its impact on economic growth negligible.

Transportation sector role

Conventional wisdom states that an increase in oil prices will slow down economic growth.

This assumption is true if oil plays an important role in the economy, as it did in the 1970s when almost all sectors were dependent on oil. Unlike the 1970s, most of the impact of higher oil prices today is limited to the transportation sector.

Fuel used in the transportation sector represents less than 2% of gross domestic product, and all transportation-related activities represent about 11% of US GDP.

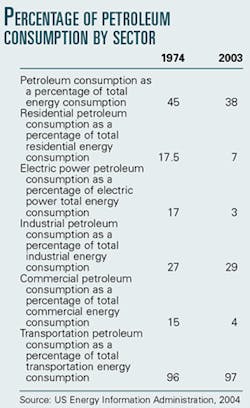

The table shows that while US petroleum consumption as a percentage of total energy consumption declined slightly, from 45% in 1974 to 38% in 2003, the decrease was not evenly distributed among sectors. Residential petroleum consumption declined from 17.5% to 7%. Electric power consumption declined from 17% to 3%. Commercial petroleum consumption declined from 15% to 4%. However, industrial and transportation consumption have remained virtually unchanged.

Other factors

Several other factors make the recent period of higher oil prices different from that of the 1970s. These factors include the timing and the duration of the increase, future expectations, and experience.1

The timing of the recent increase in oil prices relative to the business cycle was different from any previous period of high oil prices. This is the only time in history when oil prices increased after the economy hit rock bottom, which occurred soon after Sept. 11, 2001.

In all other cases, high oil prices hit the business cycle just before its peak (Fig. 1). When the economy starts from the bottom with a massive stimulus, it is impossible for high oil prices to reverse the trend.

The duration of the recent period of high oil prices is relatively short when compared with the 1970s. We are still talking about it in terms of months, while the 1970s' high oil prices lasted from 1972 to 1981. In addition, unlike the 1970s, when frequent reports indicated that the world was running out of oil and traders expected ever-increasing oil prices, most current traders and experts today believe that oil prices will decline in the future.

In fact, some experts attribute part of the decline in the US oil stocks to the backwardation in the futures market, where the forward curve exhibits a declining trend. Factories will not adjust their production lines, entrepreneurs will not invent new technologies, and consumers will not change their behavior unless high oil prices persist for an extended period of time and people expect that high oil prices will continue. A relatively short period of high oil prices accompanied by expectations of a decline in oil prices will not affect economic growth.

Unlike the 1970s, most traders and analysts expected the recent increase in oil prices.2 The possibility of the invasion of Iraq, turmoil in Venezuela, Nigeria, the Middle East, and Indonesia, increased terrorist activities around the world, and increased economic growth in China, the US, and other countries made traders and analysts forecast higher oil prices. This was not the case in 1973, 1979, 1990, or 1996. The prediction of recent higher oil prices mitigated the effect of high oil prices on the economy.

When oil prices increased suddenly in October 1973, the US had no experience on how to deal with the crisis, and it had only one oil economist. The recent increase in oil prices came after five incidents of high oil prices: in 1973, 1979, 1990, 1996, and 2000.

Previous experiences not only have prepared us psychologically but also taught us valuable lessons. For example, we have learned that price controls are among the worst policies used to mitigate the impact of high oil prices. Experience has helped mitigate the effect of high oil prices on economic growth and give investors and consumers some confidence in dealing with these issues. In fact, free oil markets could be one of the main factors that prevented an energy crisis in the US in the last 2 years, despite the numerous parallels between the oil market situation of the last 2 years and the situations in 1973 and 1979.

Summing up

Conventional wisdom states that high oil prices slow economic growth. This conventional wisdom does not apply to the recent period of high oil prices. The conditions surrounding the recent period of high oil prices are different from the conditions that prevailed in the 1970s and that helped form the conventional wisdom.

The conventional wisdom generally holds if all the variables other than oil prices and economic growth remain virtually constant. These other variables include exchange rates, government expenditures, military expenditures, interest rates, and expectations. Based on the conventional wisdom, the impact of high oil prices on the economy is worse when government expenditures decrease and interest rates increase, which was the case in the 1970s.

The current situation is different. The increase in oil prices in the 1970s was sudden, unexpected, and significant. People expected prices to continue increasing as several reports indicated that the world was running out of oil. The recent depreciation of the dollar relative to the euro and the yen limited the impact of high oil prices to the US. Several factors limited the impact of high oil prices on US economic growth. These factors include an unprecedented increase in government expenditures and an unprecedented continuous decrease in interest rates. Unlike the 1970s, oil prices have increased slowly and gradually. Traders and experts expected the increase. They also expect oil prices to decrease, which has created a backwardation in the market.

In fact, the past 2 years are the only period in OECD history when oil prices, economic growth, government expenditures, and military spending all have increased at a time when interest rates and the value of the dollar have continued to decrease.

One important factor that distinguishes the 1970s from the current situation that this article mentions but does not discuss is price control, which also contributed to lower economic growth and exacerbated the energy crises of the 1970s. Having had that experience, we have learned how to mitigate the impact of high oil prices and deal with them in other, more-productive ways. A relatively short period of high oil prices accompanied by expectations of a decline in oil prices will not affect economic growth.

High oil prices should not affect the economies of the industrial countries if recent macroeconomic trends continue. Although conventional wisdom does not apply at this time, it should serve as a reminder for politicians, policymakers, traders, and analysts that oil prices will strike back if the policies of the 1970s are repeated.

However, high oil prices may affect economic growth in the US as interest rates start to increase and government expenditures start to decrease. High oil prices will not hurt the economy on their own. But they will if they find the proper humidity, pressure, and temperature. F

References

1. For the similarities between the recent period and the 1970s energy crises, see Williams, L. Jim, and Alhajji, A.F., "Parallels with earlier energy crises underscore US vulnerability to oil supply shocks today," Oil & Gas Journal, Vol. 101, No. 5, Feb. 3, 2003.

2. Ibid. Also see Alhajji, A.F., and Williams, Jim, "Measures of Petroleum Dependence and Vulnerability in OECD Countries" Middle East Economic Survey, Vol. XLVI, No. 16, April 2003. Both studies predicted an increase in oil prices.

The author

A.F. Alhajji (a-alhajji@ onu.edu) is an associate professor of economics at the University of Northern Ohio at Ada, Ohio. He was a research assistant professor and visiting assistant professor at Colorado School of Mines during 1997-2001. He taught for 3 years at the University of Oklahoma, where he received his PhD in petroleum economics in 1995. Alhajji has published more than 300 articles and columns.