Tanker trade will benefit from Caspian, Black Sea events

Conditions in the Caspian and Black seas continue to create problems as well as opportunities for the world's petroleum shipping industry—but not always in expected ways, according to analyses released last month by New York-based shipping consultant Poten & Partners Inc.

Frequent bottlenecks for crude oil moving by tanker through the Bosporus Strait, says one analysis, will force adjustments to movements of crude oil from West Africa, the Caribbean, and the North Sea and likely lead to more Persian Gulf crude oil supplying Atlantic Basin refineries. Panamax, Aframax, and Suezmax tankers will benefit from such adjustments.

Tanker trade will benefit—not suffer, says another analysis, from completion of the Baku-Tiblisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline, scheduled for 2004. More vessels will be needed from Ceyhan to Mediterranean refineries, first of all, as well as to Northern Europe refineries to replace declining production from North Sea fields.

Bosporus bottleneck

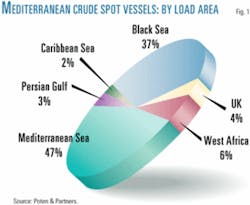

The Suezmax and Aframax markets, according to Poten & Partners, saw rate hikes in late 2003 driven partly by unplanned delays of up to 20 days in the Bosporus.

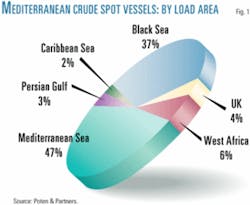

Fig. 1 shows how rates were affected; Fig. 2 shows how Black Sea crude exports were up on the spot market in each of the last 3 years.

Black Sea crude oil carried in spot-market tankers over the same 5-week period totaled 5.4 million tons in 2001, 7.7 million tons in 2002, and 7.9 million tons last year.

"This is an impressive rate" of growth of 21%/year, says the Poten & Partners' analysis, although crude exports in 2003 were "not that much ahead" of those in 2002.

But the growth of Black Sea exports will likely cause more, not less, congestion in the Turkish Strait. Tankers longer than 200 m must move through the strait only in daylight, under Turkish law. Limiting tanker traffic reduces the chances of an oil spill from collision or grounding but also caps the number of tanker transits.

"As system capacity is approached, it doesn't take that much of a delay to cause an impressive queue of tankers U triggered by more fog than usual for this time of year," says Poten & Partners.

At the first week of December, for example, 53 tankers longer than 200 m were awaiting northbound transit and 16 tankers longer than 200 m were awaiting southbound transit through the strait.

Table 1 shows approximate waiting times for passing through the Turkish Strait, according to the analysis.

Black Sea crude in the Med

Fig. 3 shows the shipping distribution of Black Sea crude in the Mediterranean, where most Black Sea crude has been destined: More than a third of Mediterranean crude activity comes from the Black Sea.

Because bottlenecks in the Bosporus seriously affect crude oil supply, other sources—such as West Africa, the Caribbean, and North Sea—must be tapped to supply Mediterranean refineries. Panamaxes, Aframaxes, and Suezmaxes, says Poten & Partners' analysis, benefit when replacement oil comes from the Atlantic Basin, increasing voyage length.

Most Atlantic Basin crude is already dedicated to North American and northern European refineries. Crude diverted to satisfy Mediterranean requirements makes replacement crude necessary for US and UK refineries.

The net result of the "Bosporus bottleneck is a larger number of cargoes" from the Persian Gulf to supply Atlantic Basin refineries.

BTC pipeline

The consultant also believes that completion of the BTC pipeline, set for later this year, may pose less of a threat to shipping interests than many fear.

In fact, Caucasian crude oil that will initially move through the line may be headed—by tanker from Ceyhan—to Europe to replace North Sea crude production that "is showing the first signs of a long-term decline." Asian markets are also possible destinations for Caucasian crude oil.

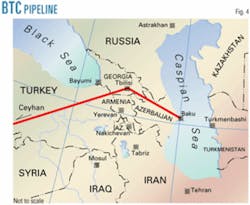

The BTC pipeline extends 1,760 km from Baku (Azerbaijan) to Tiblisi (Georgia) then to Ceyhan (Turkey) on the Mediterranean Sea, terminus also of the Iraq-Turkey pipeline (Fig. 4).

BP PLC leads the consortium of owners building the pipeline, which is to be operating by next year. The pipeline was to be 40% completed this month, but estimates at the time of Poten & Partners' analyses in December were that the pipeline was only 25% complete with about one-third of the Georgia portion complete.

Events in Georgia have complicated completion of the $1.8 billion financing, according to the analysis. Georgia lacks oil resources and is the focus of attention in the world of oil and tankers, says Poten and Partners, as two pipelines cross the nation.

One carries Azerbaijan crude to the Georgian Black Sea port of Supsa. The other is or will be BTC.

The situation in Georgia at yearend 2003, however, threatened to roil progress toward the pipeline's completion:

Popular anger at Georgia's President Eduard Shevardnadze forced him to resign in late November after his Nov. 2 reelection was widely perceived as rigged. Shevardnadze was a strong proponent for the BTC pipeline passing through the country rather than via a shorter route through Armenia, which would have been challenged by Azerbaijan.

Georgia's new provisional government faces continued fragmentation of the country by the autonomous regions of Abkhazia, Ajaria, and South Ossetia, which are being courted by the Russians, according to Poten & Partners.

As a counterweight, the new regime is trying to move closer to the West; the US announced an intention to aid the provisional government financially and provide security assistance. This is complicated, however, by remaining Russian military bases in Georgia.

Completion of the BTC pipeline will likely remain a priority of the Georgian government as a source of revenue through transit fees to help alleviate the grinding poverty of the nation and stabilize the current regime, says Poten & Partners.

Tanker implications

The BTC pipeline could be interpreted as negative, says the analysis, because Caucasian crude has the potential to displace Persian Gulf oil in the Atlantic Basin, decreasing ton-miles by cutting back on the key Cape of Good Hope VLCC trade.

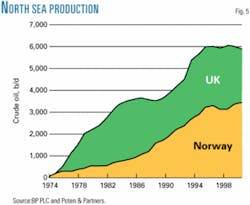

But Caucasian crude will actually be needed to replace North Sea crude, says the analysis. Rising production in the Norwegian sector is offsetting declining production in the UK sector (Fig. 5), but further oil discoveries and development of known fields cannot keep up with the depletion of existing fields, it says.

Aggregate North Sea production will begin a long-awaited decline in the next few years, says Poten & Partners. And—here's the point—every 250,000 b/d of North Sea crude replaced by Caucasian crude from the Ceyhan terminal will provide employment for nearly six Suezmaxes or three VLCCs.

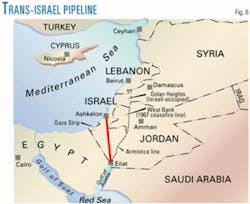

Moreover, says the analysis, completion of the BTC pipeline when coupled with the reversal of the 1.2-million-b/d Trans-Israel pipeline (Fig. 6) will benefit tanker trade and Asian refiners.

"Once the availability of Caspian crude blossoms in the eastern Med, some [oil] can be transported to Ashkelon through the Trans-Israel pipeline to Eilat on the Red Sea for transport to Asia. Crude can be shipped from Eilat in VLCCs," says Poten & Partners.

For Asian nations highly dependent on the Persian Gulf to satisfy their growing imports, Caucasian crude, like West African crude, is highly desirable as a means of reducing pollution and diversifying crude supplies. Incremental demand for substituting 250,000 b/d of Caucasian for 250,000 b/d of Persian Gulf crude as imports to China, however, will provide incremental employment for only one VLCC continuously, says the analysis.