2003 was a year of transition for the MTBE, fuels industry

The year 2003 was one of transition for the methyl tertiary butyl ether industry. A possible repeal of the oxygenate mandate that was signed into law in the early 1990s could result in supply outages, price spikes, and pollution problems in 2004 and later.

Year 2003 was mostly business as usual for refiners; however, several states announced decisions to ban MTBE from gasoline by yearend. This has begun to take its toll on MTBE production, economics, and distribution.

A new energy bill is still being debated in the US Congress that will have a significant effect on the fuels industry.

Events in 2003 have had significant effects, which include the fact that:

- Political compromise in the form of a renewable-fuels standard may reshape the fuels industry through the ethanol mandate. Fungibility and supply security are at risk.

- The complexity of the US fuel supply system may impede the industry's ability to shift fuel supplies efficiently from one geographic region to another.

- Steady growth in the US gasoline market, combined with a static supply situation, keeps plants running at capacity with little margin of safety to cover even temporary disruptions.

- There are, at most, 3 years of reserve US refining capacity to cover gasoline demand growth at recent rates.

- If MTBE is banned, the loss of 300,000 b/d of MTBE volume would use up 2 of those 3 years.

- The ethanol industry may be overbuilding capacity for mandated volumes that may erode profit margins and the ability to retire debt.

- New York and Connecticut switching to ethanol represents approximately 35,000 b/d of lost MTBE demand.

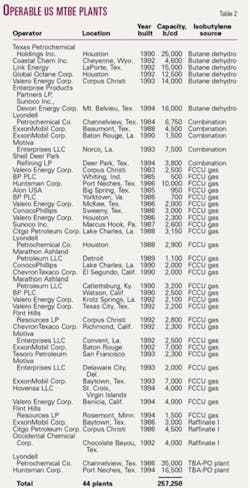

- The closure of Global Octanes Inc.'s and Link Energy LLC's plants in Houston as well as Coastal Chem Inc.'s plant in Wyoming for economic reasons represents a loss of 32,100 b/d of MTBE production capacity.

Renewable-fuels standard

This legislation has been the single most important and controversial development in the history of MTBE since the Regulation Negotiations in the early 1990s but for a different reason.

For more than 10 years, MTBE and ethanol have fought the equivalent of a turf war. For awhile, the two lobbies accepted their natural markets but were constantly looking to expand market share whenever opportunities arose.

The ethanol lobby did an excellent job of rallying farm support for fuel ethanol. MTBE supporters were secure in the fact that their product had a track record with refiners and shipped and performed well as an octane replacement for lead, benzene, and other products not conducive to maintaining clean air.

The renewable-fuels standard (RFS) resulted from political efforts to carve out a larger share of the oxygenate market. Farmers' associations and companies such as Archer Daniels Midland Co., which had interest in increased corn use, supported the ethanol portion of this movement.

The result was two versions of a bill intended to increase ethanol use and expand markets beyond farm states.

New energy legislation

In response to an initiative by the Bush administration, both houses of Congress produced basic energy bills. The Senate produced a bill that included:

*Installing an RFS mandating the use of 5 billion gal/year of fuel ethanol by 2012. This is nearly three times the present output of that industry. It would call for additions in stages beginning in 2004.

*Removing the reformulated gasoline (RFG) oxygen standard of 2%. This was intended to help ethanol with its summertime vapor-pressure problems.

*Allowing refiners that use more ethanol than mandated to sell credits to those not using as much ethanol.

*Providing a "safe harbor" provision to protect ethanol producers from lawsuits, but making no such provisions for MTBE.

*Placing the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in charge of the program, refinery by refinery. The EPA is an enforcement organization, not an operator; the feasibility of a program is not EPA's concern.

*Eliminating MTBE use in 4 years, but allowing individual states to take independent action earlier if they choose.

*Calling for studies of critical aspects of the program on a timetable that mandates action before the studies were completed.

The House of Representatives also produced a bill that was similar to the Senate version, but had some important differences. It includes:

- An RFS that mandates the use of 5 billion gal/year of fuel-grade ethanol by 2015.

- The removal of the 2% oxygen standard.

- A "safe harbor" provision for ethanol and MTBE.

- No ban of MTBE.

This process started in 2002 and fell apart several times due to some contentious issues in the bill. Drilling oil wells in the Alaskan National Wildlife Refuge, tax credits for natural gas pipelines and exploration, electricity generation, and control were just a few of the issues that divided Republicans, Democrats, and House and Senate members.

One of the most contentious issues was the topic of liability protection (safe harbor) for MTBE. The Senate version of the bill was a response to the contention that MTBE is a hazard to drinking water where it is used in gasoline.

MTBE opponents termed the product a potential human carcinogen and deemed it a "defective product."

Such labeling is the result of a series of lawsuits due to MTBE showing up in groundwater test wells. In most cases, the amount of product found in test wells was less than EPA's Drinking Water Advisory level.

The defective product lawsuits allowed water districts to sue MTBE producers when spills or leaks from underground storage tanks entered the water table.

MTBE proponents argued that the easy fix was to repair the leaking gasoline tanks or fine the party whose negligence caused the spill. A federal trust fund was created to assist local water districts with clean-up costs and help repair faulty facilities.

MTBE proponents have suggested a more aggressive use of this fund and fines to guilty parties, combined with liability protection for MTBE producers and blenders when not actively involved in actions that cause contamination or spills.

As of October 2003, ethanol supporters in the Senate threatened to filibuster any bill brought before Congress with a safe-harbor provision. GOP leadership and MTBE proponents said they would accept nothing less than their version of the bill that includes the drilling and safe-harbor provisions for MTBE.

Conference committee

In an attempt to help get the bill moving, a conference committee was formed in the summer made up of 53 Representatives and 11 Senators whose sole aim was to bridge the differences and produce the first comprehensive energy package the US has had in decades. Republican leadership in the House and Senate controlled this committee due to a slight Republican majority in both houses.

Conference leadership vowed to avoid past pitfalls by keeping the drafting of a final bill in the hands of a few staffers. They hoped, therefore, to speed the process by taking the writing of the bill out of the hands of politicians on so large a committee and avoid debate with every issue.

Future bill

On Nov. 18, 2003, the US House voted in favor of an omnibus energy bill, but the bill stalled in the Senate when MTBE supporters fell two votes short of ending a threatened filibuster (OGJ Online, Nov. 21, 2003). On Nov. 24, Senate leaders elected to drop the bill due to this lack of votes.

There is still a chance that an energy bill will pass in 2004 (see article on p. 59). Speculation from Washington insiders and contacts close to the action feel a bill could contain the following MTBE-related issues:

- There will be no MTBE ban.

- Producers will have limited liability protection.

- Ethanol will increase its mandated volume to 3.1 billion gal/year from 2.8 billion gal/year, beginning in 2005.

- The schedule for mandating 5 billion gal/year of ethanol will be accelerated from the 2012-15 dates provided in the initial versions of the bill.

- Language will address commingling issues, which will allow station owners some leeway.

- California will be immediately exempt from the oxygenate standard.

- Remaining states will receive exemption 270 days after California.

This assumes no last-minute deal making changes the mix. Democratic leaders have asserted that they can pass the ethanol portion of the bill as a standalone issue, so that they are reserving the right to filibuster and delay passage of the energy bill.

All congressional leaders are under pressure to produce an energy package. Recent price spikes in natural gas, power blackouts on the Eastern seaboard, and gasoline prices that have risen dramatically in certain regions have made passing an energy bill a political necessity. If an impasse occurs, legislators may remove MTBE and ethanol issues from the bill and deal with them separately.

With no oxygenate standard but an ethanol mandate in place, refiners will still have more freedom to blend fuels based on economics and best available blendstocks. The strategy that refiners will use to deal with the mandate will depend on the location of refineries, mix of products, and available budget to upgrade facilities, buy credits, etc. Some of the options are:

- Biodiesel. In some versions of the RFS, biodiesel can be counted against the 5 billion gal/year mandate.

- Ethanol credits. Refiners with multiple locations may be able to blend excess ethanol volume in the Midwest and use the credits in West Coast or East Coast operations. Others may choose to buy credits from other refiners.

- Legal action. California filed legal action with EPA to discontinue the use of MTBE. With the oxygenate standard removed, California has initiated a multimillion dollar study to determine if there is any connection between ozone and air pollution and the rise in brain cancer. This could result in a cause of action to declare ethanol a "defective product" as well, given all the ozone exceedances of the past year (OGJ, Oct. 6, 2003, p. 18).

- Low rvp gasoline. California has a plan for post-oxygenate gasoline. California lawmakers claim the state can have clean air without using oxygenates. This is theoretically true; however, many are not convinced that refiners can produce enough gasoline meeting California Air Resources Board specifications to satisfy current state demand.

The language of the final energy bill will clear up a lot of the questions in the marketplace. Whatever the outcome, the American Petroleum Institute, National Petrochemical & Refiners Association, ethanol supporters, and state governments will deploy strategies quickly if the final bill does not favor their needs.

US gasoline market

The US gasoline markets continue to show robust demand growth (Figs. 1 and 2). During the past year, automobile manufacturers have offered financing deals on new vehicles; sales of gasoline-inefficient sport utility vehicles (SUVs) and trucks have never been higher.

As state and federal restrictions on gasoline become more stringent; the strategies that refiners and importers use to satisfy increased demand become more complex.

Fewer companies now control more capacity than 10 years ago, with no new facilities built in the US during that time. Importers that normally fill the void are also having difficulties with the new specifications.

National energy policy

The new energy bill is unlikely to address the main problems concerning fuel consumption, energy independence, and who pays the bill. Americans have a love affair with the automobile and see accessibility to cheap and plentiful fuel as a birthright. Until now, therefore, the national energy policy has been based on:

- Environmental policies that restrict crude production from domestic sources, such as offshore areas and in Alaska.

- Environmental policies that prevent new refineries from being built in the US.

- Tighter fuel specifications that make it more difficult to produce or import. Gasoline blends are increasingly specific to a single region, and refiners have lost the advantages of fungibility.

- More consumers purchasing SUVs and recreational vehicles, thus raising consumption substantially.

Due to these policies, gasoline demand has increased steadily and refining capacity has decreased. Some refineries, most notably in California, have closed because they were uneconomic.

Current refinery utilization is about 95%; there are, at most, 3 years of potential growth to meet increased demand. Refineries overseas are finding it more difficult to supply gasoline that meets US requirements. With the recent high prices for crude and blendstocks, refiners have allowed stocks of gasoline and distillates to fall well below normal levels.

There is little margin of safety in the system; recent retail price scares in the Midwest and California demonstrate this fact. It would be catastrophic if a major pipeline shuts down, which happened in Arizona this summer, or if major refinery accidents occur.

Legislation requires the replacement of 300,000 b/d of MTBE with ethanol plants that have not been built yet.

Gasoline: a commodity market

US gasoline is a commodity and also an essential component in the daily life of consumers. Americans feel entitled to cheap, plentiful fuel and generally are unaware of the complexity of the fuel production and distribution system that supplies their needs.

From the consumer's standpoint, the fuel is completely fungible. One can drive anywhere in the country, use locally available fuel, and notice no difference in performance.

From the standpoint of the energy complex, however, fuels are now becoming more diverse and incompatible with one another. This reduces supply flexibility, increases the cost of production and distribution, and effectively reduces the margin of safety in a tight supply situation.

Requirements for a sound market

Gasoline demand is stable, predictable, and has not changed much due to the availability and flexibility of the distribution system. All of this may change, however, with mandates that force fuel components into regional markets that affect refiners' ability to shift supplies swiftly to regions where they are needed.

There are three basic requirements in this situation:

1. Market-makers must know the rules: What are the objectives and legal requirements? How does one accomplish these objectives in the real world?

2. There must be adequate supply source with enough spare capacity to overcome common disruptions, which occur occasionally. The supply system is running at nearly full capacity and already shows signs of incipient breakdown. Recently, a pipeline problem in Arizona caused shortages and price spikes that lasted for weeks.

3. Refiners can change gasoline supplied to one segment of the market to supplement needs elsewhere. This fungibility greatly simplifies the distribution of fuels to consumers and avoids problems with having material available at the wrong time and place.

Based on those requirements, the US could experience trouble on many fronts.

In California, the governor called for the elimination of MTBE by yearend 2002. About 11% of the state's already tight supply would be replaced with something else, presumably ethanol. But more than 75% of California gasoline is controlled by federal specifications.

The California Air Resources Board feels that some relaxation of the federal oxygen requirement would be needed for satisfactory blending with ethanol. After nearly 2 years, the federal government is still wrangling with an answer.

On the East Coast, New York and Connecticut voted to eliminate MTBE from RFG. This raises ethanol logistics issues and the possibility of dividing the market with many local custom blends.

Refiners, blenders, and importers of gasoline to this region are therefore faced with potential blend and distribution problems. Any incorrect assumption in demand can result in shortages and price spikes that will not easily or can quickly be solved.

Areas of the country that are contemplating a switch to ethanol will require special handling and segregated storage from MTBE-based blends. The East Coast in particular will have some problems.

The East Coast currently consumes approximately 1.1 million b/d of RFG or about 40% of the US total (Fig. 3). Of that amount, refineries in Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey supply about 55%, with the US Gulf Coast supplying an additional 29%. Imports make up the balance of the gasoline pool.

With New York and Connecticut administering a ban on MTBE, suppliers will face the dilemma of supplying reformulated blendstock for oxygenate blending to New York while blending MTBE in the rest of their distribution area. Such arrangements will mean separate storage, no product commingling, and an increased chance of product outages and price spikes.

US MTBE production

MTBE producers have come under extreme pressure during the past year. Production cost has become a major issue as natural gas hovered near $9.00/Mcf and butane and methanol prices have remained high.

The combination of high raw material costs, lawsuits, potential federal bans, and competition with foreign government-subsidized MTBE producers has made the market a hostile place for US producers. With no natural allies, a lack of margins, shrinking markets, and increased competition, many producers have shut down capacity.

null

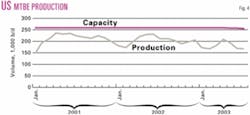

In 2003, Global Octanes and Link Energy (then EOTT) decided to cease production of MTBE in their world-scale facilities. Several smaller regional units have also had to cease or cutback production due to changes in state laws affecting MTBE usage (Fig. 4).

Although many plants have ceased production, they are still included on our list of MTBE facilities (Table 2). They are still capable of restarting; until they are dismantled, converted, or sold for another purpose they should still be considered as available capacity.

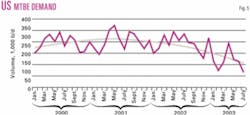

Overall MTBE demand has declined substantially as California refiners began switching to ethanol. MTBE production has slipped to about 64% of capacity in response to declining demand (Fig. 5).

US ethanol production

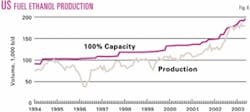

In light of these legislative attempts to mandate ethanol, it is not surprising that production has rapidly increased in 2003. Current active ethanol production has increased by more than 37% in 2003 alone (Fig. 6).

Plants currently under construction will increase supply by another 20% by yearend 2004. Another 1.3 billion gal/year of capacity is in the planning stage and potentially will be running by 2006 or earlier.

The ethanol industry has responded so quickly to the new opportunity that it may overbuild and overrun the new market's ability to absorb production. Ethanol producers may be able to meet the 5-billion-gal/year mandate well before 2012.

Currently there are 75 active ethanol plants in the US with a combined plant capacity of nearly 3 billion gal/year. This total nearly matches the mandated volume of 3.1 billion gal/year currently set for 2005.

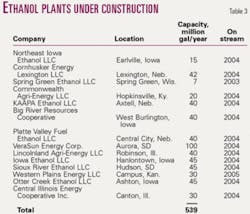

Table 3 shows that an additional capacity of 539 million gal/year is currently under construction; the majority will be available in 2004. There are currently another 39 projects announced with a total capacity of 1.3 billion gal/year.

Table 3 only lists the ones that have a reasonable chance of being built. There are many more that have been announced but are unlikely to secure financing. Most of the plants that have good financing are contemplating completion dates in 2005.

If these plants are built, the industry will have a total capacity of 4.8 billion gal/year by late 2005. Refiners will probably not find a place for this additional 1.7 billion gal/year of product without serious price concessions. The new plants may not be profitable in an oversupplied market.

Unless the US Congress develops an accelerated mandate program or other uses for fuel-grade ethanol, many of these plants may meet with less than favorable results in the marketplace. The potential oversupply could lead to price discounting that would substantially undermine these plants' ability to retire debt.

Based on a presentation to the 12th Annual DeWitt Global Methanol & Clean Fuels Conference, Oct. 28-30, 2003, Houston.

The author

Rich Lamberth is a vice-president with DeWitt & Co. Inc., Houston, responsible for managing DeWitt's MTBE/oxygenates and clean-fuels services. He has more than 27 years' management experience in the refining and petrochemical industries. Lamberth previously worked for Valero Refining Co. and Enron Capital and Trade Resources. He holds a BS in accounting and marketing from Northern Illinois University, DeKalb. He has served as vice-chairman on the Oxygenated Fuels Association's and American Methanol Institute's board of directors.