WoodMac: Acquisitions drive value creation, loss

Acquisitions remain an important driver for growth for most upstream companies, especially if these companies have failed to meet market-anticipated production goals. But acquisitions don't always create value—strategies must be employed to ensure the creation of value, according to Edinburgh-based consultant Wood Mackenzie Ltd. in the recently released report, "Value creation through acquisitions."

The report is a sequel to a study WoodMac released last February on creating value through exploration.

In the megamergers of the late 1990s, for example, many companies sought to add value through acquisitions, both by replacing reserves and by reducing costs.

"For some companies the need to replace reserves that have been produced and to be able to achieve a sustainable growth in production has underpinned their level of acquisition activity," WoodMac said.

But for some companies, study author David Black said, deals might not always bring value with them.

"Although acquisitions have delivered a step-change in growth, even for some of the biggest players in the upstream industry, it has, to date, been less clear whether these deals have created value for the purchaser," Black noted.

The acquisitions

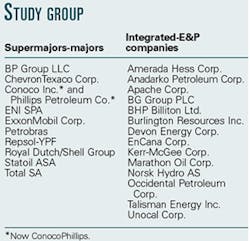

In evaluating the acquisitions of 25 companies that made acquisitions during 1996-2000, WoodMac studied nearly 170 international and Gulf of Mexico deals, excluding Canada and onshore US Lower 48 deals (see table).

WoodMac said the companies acquired more than 65 billion boe of commercial reserves during the study time frame, and 12 companies overall achieved value creation through acquisitions, while replacing reserves at the same time, according to the report.

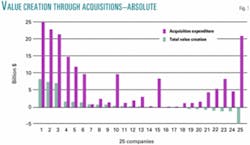

Researchers found that the companies' total investment of $140 billion—equivalent to about $180 billion in net present value (NPV) terms—resulted in the creation of $23 billion in net value, generating a 12% rate of return. So value was created for some of the companies making acquisitions. Of these, 16 created value through acquisitions, but 9 acquired assets that now are worth less in NPV terms than the company paid for their acquisition, Black said (Fig. 1).

"In absolute terms, the companies with the biggest acquisition spending have seen the largest value creation and, paradoxically, some of the biggest value erosion," Black noted.

Six companies made a 14% nominal or better return on investment, Black reported. "This is an excellent performance and will allow these companies to maintain a strong return on their capital employed. Nine companies have not achieved a 10% rate of return on their acquisition expenditure. Most of these companies probably are, however, at least exceeding their cost of capital, and internally they may perceive value creation through their acquisitions, where we show value erosion on a more demanding 10% nominal discount rate hurdle."

Black said that the difference between assets valuation at the time of the deal and the actual purchase price—the deal premium paid to acquire assets—accounted for $9 billion of the value erosion (in NPV terms). Some of these losses resulted from companies in bidding environments overpaying large premiums for fear of losing the intended acquisition.

Acquiring reserves

The oil price, in aggregate, was by far the most significant value driver, accounting for $25 billion of value creation (in NPV terms), Black said. "It is difficult to know to what extent companies making acquisitions, particularly when oil prices were low, had a countercyclical strategy," Black said. "For some, the ability to use relatively highly rated equity to acquire lower-rated target companies may have been a key factor in their deals. For the brave, the benefits have been considerable, despite the risks," he added.

Discoveries from assets acquired accounted for about $4 billion, and another $2 billion resulted from cost reductions and changes to the value of the assets acquired through increased reserves. Many companies have added significant commercial reserves through their acquisition strategies. The companies' acquired reserves gave "a commercial reserves replacement ratio of 160%," with 20 of the companies having commercial reserves replacement ratios of more than 100%. These include both those with small international production and some large companies through megamergers.

The acquisition margin

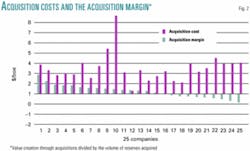

Cost comparisons between deals based on the price per barrel of oil equivalent do not give the true value of the reserves acquired.

Some seemingly high-cost deals may actually deliver better value for the purchaser because of the acquisition margin.

"This is the value creation through acquisitions divided by the volume of reserves acquired—in essence, the NPV added by each barrel acquired (Fig. 2)," Black explained.

Volume vs. value

The ideal objective is to create value through acquisitions, and there may be other motives for making acquisitions, such as the simple desire to expand the company, to prevent a competitor from acquiring the asset, or as a defensive ploy to avoid becoming a tempting target oneself.

However, there are limits to the strategy of increasing acquisitions to offset production slowdowns and a lack of reserves, Black said. "A company may simply not be able to identify acquisition targets worth pursuing, or have the cash flow to fund them—and there will often be competition with other potential purchasers."

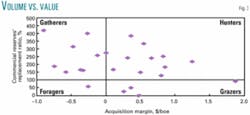

The 25 companies studied employed different strategies in acquiring assets and obtained different results. WoodMac has placed them into four categories for purposes of identifying their commercial reserves replacement ratios through acquisitions (Fig. 3).

In Fig. 3, the axes cross at an acquisition margin of $0/boe and the commercial reserves replacement ratio through acquisitions of 100%, said Black. "This allows us to define a universe of four quadrants based on the results achieved by the companies." He said the companies were depicted as

- "Hunters"—Companies creating value and replacing reserves—the ideal position.

- "Gatherers"—Companies replacing reserves but having negative acquisition margins.

- "Grazers"—Companies creating value through acquisitions but not replacing reserves.

- "Foragers"—Companies combining eroding value through acquisitions and failure to replace reserves. They are very dependent on their exploration strategy.

The companies assessed employed different acquisition strategies, Black said, some being aggressive bidders that paid premium prices. Others leveraged skills to create value from increasing their reserves and cutting costs on acquired portfolios. Many benefited from the recent strength in oil prices, particularly those that were prepared to be countercyclical when others were more cautious.

From these strategies, 12 companies have attained value creation through acquisitions and simultaneously replaced their production with acquisitions of commercial reserves. "If exploration is an enigma, acquisitions are an amalgam," Black said. "Premiums are out and upsides are in. Knowing how to avoid paying for some and having strategies for capturing others are the keys to value creation through acquisitions."