CPC, BTC pipelines make current Caspian area oil export capacity adequate

Traditionally oil production in the Caspian region has been constrained by a lack of export infrastructure. But with Caspian Pipeline Consortium's pipeline (CPC) operational since 2001 and Baku-Tblisi-Ceyhan Pipeline Co.'s pipeline (BTC) operational from 2005, this problem has eased considerably.

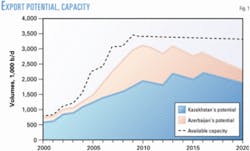

Wood Mackenzie Ltd., Edinburgh, expects that current export capacity in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan will be sufficient to handle forecast exports. Additional routes may still be constructed, however, if they offer economic, logistical, or political advantages.

In Kazakhstan, exports via the CPC pipeline have been lower than planned but will likely increase significantly in 2004 when transportation of Karachaganak crude commences. CPC capacity accounts for the bulk of Kazakhstan's usable export capacity over the medium term.

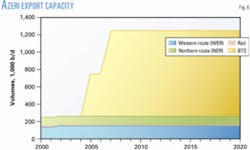

In Azerbaijan, the BTC pipeline is on course for completion in early 2005 when transportation of Phase 1 Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli (ACG) crude will commence. BTC will dominate Azerbaijan's export capacity for the foreseeable future and seems likely to transport volumes from Kazakhstan also (Fig. 1).

Considering both production potential and domestic demand has allowed Wood Mackenzie to calculate export potential. Kazakhstan has the potential to export 2 million b/d around 2010, and Azerbaijan 1.2 million b/d around 2009. Production in Kazakhstan is largely attributable to the key developments of Kashagan, Tengiz, and Karachaganak; production in Azerbaijan is dominated by the ACG development.

There are several future pipeline projects under discussion in the Caspian area, the highest profile one being the Kazakhstan-China pipeline. KazMunaiGaz has announced plans to start work on the Atasu-Alashankou section in mid-2004. Questions remain, however, over volumes that could be committed to the line and its economic viability.

Pipelines, export routes

The following examination of key export routes in the Caspian region includes rail and sea export routes as well as pipelines.

Kazakhstan

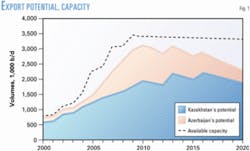

The 1,580-km CPC pipeline links the Tengiz field directly to a dedicated marine terminal at South Ozereika near Novorossiisk on the Black Sea. The route runs via Atyrau in Kazakhstan and Astrakhan, Komsomolsk, and Kropotkin in Russia.

In 2003, CPC transported about 310,000 b/d, an increase of 33% over 2002 volumes (Fig. 2).

Construction of facilities for CPC began in May 1999 following approval, by the Kazakh and Russian governments, of a feasibility study to construct the line. Actual pipe laying began in November 1999, and on official completion of the initial construction project in late 2002, CPC became fully operational.

CPC's operation under a "test regime" ended on Apr. 28, 2003, when the governments of Russia and Kazakhstan signed the last acceptance papers. This marked the official beginning of commercial operation.

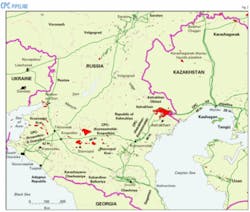

CPC shareholders (Table 1) are obliged to fill their throughput allocations or pay a waiver fee for the shortfall (providing that the technical capability to load the crude exists). Throughput in 2001-03 was below initial expectations but will increase markedly this year when substantial volumes of Karachaganak liquids will be supplied. The bulk of current CPC throughput comes from TengizChev-roil's Tengiz field.

Crude supplies from Karachaganak to CPC were to begin in September 2003 but were delayed by contaminants (caustic soda) in the newly completed link line from the field to Atyrau. Exports are now expected by midyear (OGJ Online, Sept. 25, 2003; Dec. 9, 2003).

Karachaganak will be the seventh shipper in CPC, with KazMunaiGaz in particular being quick to sign up volumes from its subsidiaries and joint-venture partners in 2003.

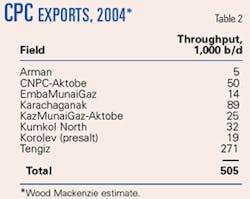

Table 2 presents estimates of 2004 exports.

CPC capacity expansions comprise the key element in the growth of Kazakhstan's export capacity, although the timing for these is uncertain. Kashagan crude is likely to fill any ullage in the medium-term after commercial production commences in 2008.

The line's initial capacity of 560,000 b/d requires 5 pumping stations. It was originally envisioned that ultimate capacity of more than 1.3 million could be achieved in four phases through the addition of the 10 new pumping stations.

Until completion of CPC in 2001, the Uzen-Atyrau-Samara crude oil pipeline was Kazakhstan's principal export line. It was put into operation between 1970 and 1978 and originally transported crude from the Uzen field to Russia.

Kazakhstan has an agreement with Russia allowing it to pump 340,000 b/d into the Transneft system via the Atyrau-Samara line in 2004 but may struggle to meet this target as Kazakhstan continues to increase exports via CPC.

Between Uzen and Atyrau the pipeline is 40 in. OD with a capacity of 500,000 b/d. The 210,000-b/d capacity of the 28-in. Atyrau-Samara section was previously the main technical constraint to Kazakh oil exports. Upgrading of the line's capacity to 300,000 b/d by adding a new pumping station and modernizing existing facilities was completed in November 2000 at a cost $37.5 million.

In November 2002, KazTransOil announced a $200-million project to reconstruct and expand the Atyrau-Samara section of the pipeline over three stages:

- Stage I. Addition of drag-reducing agents to the oil (2004) could raise capacity to about 340,000 b/d.

- Stage II. Refurbishing the current system (line and pumping stations) would increase capacity to 380,000 b/d.

- Stage III. Adding new sections of line will increase capacity to 500-600,000 b/d.

In addition to these key Kazakhstan export pipelines, capacity also exists in the Kenkiyak-Orsk and Karachaganak-Orenburg pipelines. The usable capacity of these pipelines has decreased, however, as more attractive routes have become available.

Completion of the Kenkiyak-Atyrau line has diverted volumes from the Kenkiyak-Orsk line, and completion of the Karachaganak-Atyrau link into CPC will similarly divert volumes from the Karachaganak-Orenburg line.

In addition, the 440,000-b/d Omsk-Chardzhev line has usable capacity only if the northern section were reversed to allow exports to the Omsk refinery (and beyond). This would be at the expense of supplies, however, that are currently swapped southwards to supply the under-utilized Pavlodar refinery and is thus thought unlikely.

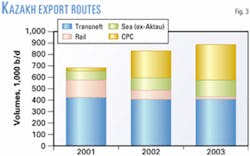

Rail and sea exports accounted for about 21% of total Kazakh exports in 2003, down from 32% in 2002 (Fig. 3). The reducing volumes are primarily due to reduced rail exports and increased use of CPC.

Use of Aktau as a conduit for exporting crude via the Caspian Sea has risen considerably over recent years and 145,000 b/d were exported in 2003. It is expected to continue to be well used in the future but would require substantial upgrading to handle additional volumes that could transit the port to Baku for transportation via BTC.

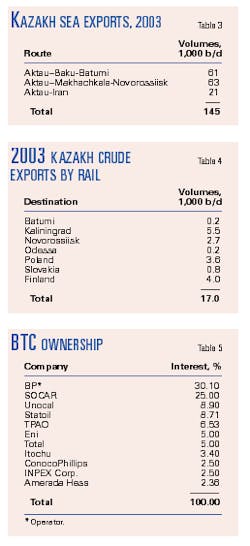

Table 3 presents marine exports of Kazakh oil; Table 4, rail exports. In 2003, Kazakhstan moved by rail about 17,000 b/d, via Russia, to seven key destinations.

Rail exports have fallen dramatically in recent years with the expansion of cheaper pipeline capacity. Rail exports totaled 57,000 b/d in 2002 but fell to 17,000 b/d in 2003. In 2003, Kazakhstan also exported 25,000 b/d of crude to China through the Druzhba station.

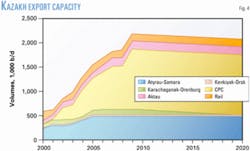

Fig. 4 shows the usable capacity available in Kazakhstan to 2020, split by export route.

Azerbaijan

The Baku-Tblisi-Ceyhan pipeline will transport ACG crude from Baku to Ceyhan, Turkey, via Tblisi, Georgia. The pipeline will be the primary route for exporting Azeri crude to world markets. Table 5 presents the BTC ownership distribution.

Construction on the BP-led project began in April 2003 with completion expected by yearend 2004. First volumes of ACG crude will move through the line in early 2005.

The 1,760 km, 34 and 46 in. pipeline will be buried to 1 m and, at full capacity, require 98 valve stations and 8 pumping stations (2 each in Azerbaijan and Georgia and 4 in Turkey).

Initial capacity will be 500,000 b/d in 2005, increasing to design capacity of 1 million b/d in 2006, following construction of the final pumping station. BP has said that capacity could be increased to 1.4 million b/d with use of drag-reducing agents and by a further 200,000-400,000 b/d by adding pump stations.

Wood Mackenzie estimates use of the BTC line to be 80-100% between 2008 and 2013 with Azeri volumes alone. The Shah Deniz consortium has announced it will produce condensate volumes of around 250 million bbl under Phase 1 development. Condensate exports from the field will likely peak at around 40,000 b/d.

Fig. 5 shows the export pipelines for Azerbaijan. The export capacity forecast for the country is that there is spare capacity in BTC for possible future exports from Kazakhstan, although space will be limited 2008-11, when ACG is at peak production.

Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan have already begun discussions on use of the BTC pipeline and a protocol was signed in September 2003 following a round of talks in Baku. Azerbaijan's President Heidar Aliyev has said that the inter-governmental agreement between the two countries could be signed this year.

Kazakhstan could export 200,000-400,000 b/d by tankers to Azerbaijan. It is likely that crude transported from Kazakhstan will include production from the Kashagan field when it begins commercial production in 2008. Total, Eni, ConocoPhillips, and Inpex Corp. together hold a 59% stake in Kashagan and 15% stake in the BTC pipeline.

Currently, however, no Kashagan volumes have been officially committed to the BTC line.

Some volumes of exported oil from Georgia and Turkmenistan could also use the BTC line, but these volumes are extremely small in comparison to Azeri and Kazakh exports.

The South Caucasus Gas Pipeline (SCP) will export Shah Deniz gas to Turkey and is being built alongside the BTC pipeline to realize cost savings for both projects. The BTC pipeline will be laid to the Georgia-Turkey border at which point the pipeline team will turn around and lay the SCP back to Baku.

The Western Export Route (WER) pipeline, operated by the Azerbaijan International Operating Co. (AIOC), is currently Azerbaijan's most important export route, transporting the majority of ACG crude to world markets via Supsa on the Black Sea. AIOC funded a rehabilitation project to put the Soviet-era pipeline back into operation in 1996.

Capacity on the 830 km, 21-in. OD Baku-Supsa pipeline was upgraded to 130,000 b/d from 115,000 b/d in early 2001 to maximize production from the ACG early-oil phase. Further expansion of the pumping stations increased capacity to about 140,000 b/d in mid 2002 and BP had plans to increase capacity further to 145,000-155,000 b/d in 2003.

WER is exclusively used by AIOC; there are unlikely to be export opportunities for third-party users in the short-to-medium term.

The 100,000-b/d Northern Export Route (NER) pipeline was extensively refurbished and upgraded and began transporting Azeri oil from Sangachal to Novorossiisk on the Black Sea coast of Russia from November 1997.

Within Azerbaijan, the route runs from the Sangachal terminal via Shah Kaya, Guzdak, Sumgait and Siazan to Shirvanovka and the border with Russia. Total length within Azerbaijan is 224 km. The existing 167 km, 28 in. pipeline from Sumgait to Shirvanovka has been refurbished and a metering station installed at the Azeri-Russian border.

In Russia, the route continues north to Shamkhal in Dagestan (308 km), then westwards, bypassing Chechnya to the east, and on to Tikhoretsk (571 km). A 226-km stretch connects Tikhoretsk with Novorossiisk.

Following the AIOC's transferal of its entire export stream into the WER in June 1999, the southern route has been left exclusively to crude exports by Azerbaijan's SOCAR (State Oil Co. of the Azerbaijan Republic). SOCAR moves 50,000 b/d of oil along this route and is likely to continue to use the line until commissioning of the BTC pipeline, when exports via NER may reduce.

In early 2004, Russia expressed interest in signing a 15-year agreement with Azerbaijan on the use of the NER. Azerbaijan, however, is reluctant to sign any long-term agreement due to the anticipated start-up of the BTC pipe- line. Fig. 6 shows the export capacity available in Azerbaijan to 2020, split by export route.

Export potential

Having considered the export capacity in both Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, this discussion must now examine the export potential of these countries to determine if sufficient capacity exists in the short and medium terms.

Export potential has been derived from Wood Mackenzie's field-by-field assessment of production potential and an evaluation of domestic demand.

Production potential

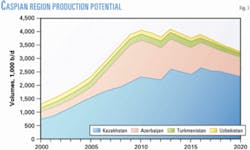

Despite expectations of significant production increases in Azerbaijan (primarily from ACG), Kazakhstan will still dominate the regional production picture for the next 20 years.

Peak production will be around 4.0 million b/d in 2010-14. Kazakhstan's peak production of 2.6 million b/d, expected in 2013, will offset the forecast initial decline from Azerbaijan (Fig. 7).

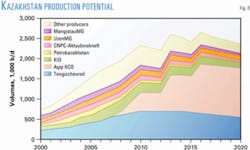

- Kazakhstan. Fig. 8 shows the production profile for Kazakhstan, split by key producing fields. From 2010 on, Kashagan and Tengiz production dominates the profile.

The primary constraint on liquids production in Kazakhstan is likely to be limitations on gas utilization. Limited local demand for associated gas production at key projects such as Tengiz, Karachaganak, and Kashagan could inhibit the pace and scale of field developments or expansions.

The Karachaganak partners have already indicated that the next expansion phase cannot take place until a secure gas-marketing option is in place. This alone could remove 130,000-160,000 b/d from the production forecast in 2006-11. In addition, further disputes between operators and government, such as those experienced at Tengiz and Kashagan, could lead to additional slippage.

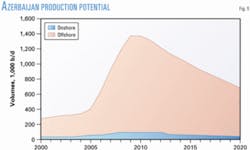

- Azerbaijan. Oil production in Azerbaijan has been increasing since 1995, reaching 315,000 b/d in 2003, of which the Chirag field produced 133,000 b/d. Continued near-term growth of oil production in Azerbaijan will largely reflect the pace of development on the Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli contract area.

Wood Mackenzie estimates Azeri production growing to about 1.4 million b/d by 2009 based on existing discoveries only. The Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli fields remain the only substantial proven oil reserves within this forecast.

Fig. 9 clearly illustrates that most of the oil production in Azerbaijan is now offshore (90%), while the onshore fields have maintained production at about 30,000 b/d for the past 10 years.

Although several foreign investors are focusing efforts on onshore developments, the scale of these projects is small compared with offshore and is therefore expected to become progressively less important to future Azeri oil production.

Future production in Azerbaijan relies on two key elements: the effective development of the Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli contract area (which itself depends on BTC being operational in 2005) and any significant exploration success in the major offshore prospects, although this is now unlikely.

Domestic demand

Kazakhstan's crude demand is currently about 200,000 b/d, most of which is consumed on the domestic market, although small volumes of oil products are exported.

Wood Mackenzie anticipates that domestic demand will increase by around 4%/year until 2007, slowing to 3%/year thereafter. It is assumed that continued improvements to the Kazakhstan economy will fuel demand in both domestic and industrial sectors (Fig. 10).

Azerbaijan's domestic oil consumption declined rapidly after the breakup of the USSR and the collapse of the industrial base. As a result of growing oil export revenues from 1997 onwards, however, the Azeri economy is slowly reviving. While this was dampened by low oil prices during 1998 and early 1999, growth in oil consumption revived in 2000. Domestic growth fueled by the increasing oil-export revenues will move consumption up by about 5%/year.

Additional routes?

Having considered both production potential and domestic demand, we have calculated export potential of 2 million b/d around 2010.

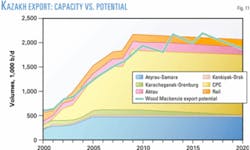

Fig. 11 shows Kazakhstan's export capacity vs. export potential. There appears to be a surplus of capacity for predicted exports, suggesting that additional routes are not needed. In reality, however, new routes could still be constructed, provided they can compete economically with existing routes.

Most producers in the Caspian favor multiple export routes because they could provide lower transport costs and potentially logistical and political advantages.

Wood Mackenzie expects that the much-discussed option to export Kazakh crude across the Caspian Sea and then via BTC could compete economically with existing routes, particularly against costly rail exports. It is therefore likely to be attractive to Kazakh producers as it is a large-scale, independent route that has some logistical and political advantages.

Most existing exports from Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan ultimately rely on tanker transport from Black Sea ports. In 2003, bad weather and new stricter legislation led to significant delays and disruption to exports via the Bosporus Straits. This has improved the competitive position of the "Bosporus bypass" options such as the BTC and Odessa-Brody pipelines (OGJ, Mar. 8, 2004, p. 64).

Other pipeline projects in discussion in the Caspian region include the Kazakhstan-China pipeline and the Kazakhstan-Iran pipeline.

The Kazakhstan-China pipeline in particular has received strong political support from both the Kazakh and Chinese governments. Massive investment will be required to construct the line, however, and questions remain over volumes that could be committed to the line and its economic viability.

Despite this, KazMunaiGaz has announced that it plans to start constructing the Atasu-Alashankou section in mid-2004.

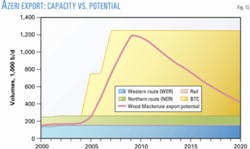

Exports in Azerbaijan will increase rapidly from 2005 as the Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli field development accelerates (Fig. 12).

Wood Mackenzie anticipates that Azerbaijan could be exporting more than 1 million b/d by 2009.

To facilitate this, it is assumed that the BTC pipeline project continues on schedule and will be operational from early 2005. If Azerbaijan is to retain its strong export potential, then significant new discoveries will be needed to maintain production beyond 2012-13, after Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli production begins to decline, but this now seems unlikely. F

The authors

Mark McCafferty (mark.mccafferty@woodmac. com) is an energy analyst for the Caspian region for Wood Mackenzie Ltd., Edinburgh. Since joining the firm, he has undertaken a wide range of research and consulting assignments across the independent states of the greater Caspian region. He specializes in the petroleum sectors of Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan and in assessing the impact of the petroleum and economic superpowers on the development of the Central Asian energy industry. Previously, McCafferty was a project executive with Scottish Enterprise's energy team in Aberdeen. He holds a BSc (honors) in technology and business from Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen.

Valentina Kretzschmar ([email protected]) is also an energy analyst covering the Caspian region for Wood Mackenzie Ltd. Since joining the firm at the beginning of this year, she has been involved with analyzing the upstream sector of the greater Caspian region. She specializes in the upstream and midstream industries of Azerbaijan and Georgia and has assumed responsibility for the ongoing development of our research products in the Caucasus region. Previously, Kretzschmar was a petroleum engineer with Edinburgh Petroleum Services Ltd. and research fellow in energy group at the University of Edinburgh. She holds an MSc in advanced mechanical engineering from Imperial College, London, and a BEng (honors) in engineering from the University of Edinburgh.