A new report from the UK government warmly embraces the idea of moderating emissions of carbon dioxide with projects that raise oil production. It also raises a question: Will environmental interest groups make it a group hug? The answer will say much about motives in controversies over global warming.

So far, environmental groups have stayed quiet about the use of captured CO2 for enhanced oil recovery. A 1999 study by Greenpeace addressed injection of the greenhouse gas into subsea aquifers, a technique Statoil ASA has employed at Sleipner gas and condensate field off Norway and plans to repeat. In that report, chiefly about CO2 sequestration in oceans, Greenpeace expressed concern about the potential of the injectant to escape reservoirs possibly unsuited to its containment. But neither it nor any of the other major environmental groups has loudly protested injection as a way both to dispose of a gas suspected of raising average global temperature and to increase recovery of oil and gas. Yet.

Established technique

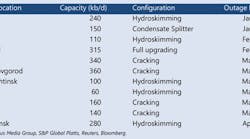

Injection of CO2 for EOR is not new, of course. In the US, mainly in the Permian basin of Texas and New Mexico, operators at the beginning of this year were producing 206,000 b/d of oil beyond primary and secondary output via CO2 injection (OGJ, Apr. 12, 2004, p. 45). While most schemes use purchased CO2 from natural deposits in Colorado and New Mexico, the number of projects injecting waste gas that otherwise would be vented is growing. Also growing is interest in injection of CO2 into coal beds for sequestration of the injectant and mobilization of methane.

A practice well established as a way to improve oil and gas recovery thus has gained serious and growing attention as a method for mitigating the atmospheric build-up of CO2. The Society of Petroleum Engineers and US Department of Energy, for example, included a session on CO2 sequestration in their biennial symposium on improved oil recovery this month in Tulsa.

A study released before that meeting by the UK Department of Trade and Industry updates a governmental effort to bring the marriage of CO2 sequestration and EOR to the North Sea. It also documents doubts within industry about the idea. Producers surveyed by DTI don't think dual-purpose CO2 injection makes economic sense in the North Sea under current conditions. They also don't think credits available at expected values under the European Union's Emission Trading Scheme would make the technique commercial.

"If EOR is to be deployed broadly in the UK North Sea," the study observes, "additional market changes will be needed." The change mostly likely to come from government would be tax incentives for EOR. A separate study just beginning on mature North Sea fields will cover tax changes, the study added.

Citing "the low level of interest shown by key stakeholders"—power generators and equipment suppliers as well as producers—DTI decided against early implementation of the full-scale demonstration project considered by its study. But the ambition endures. DTI concluded that a demonstration of CO2 capture and storage (CCS) "should be done as part of an overall strategy for the development of near to zero emission fossil fuel technologies."

The message is clear. DTI wants something that the market, without tax subsidies, does not. The official push no doubt comes from strong political pressure in Europe for action on global warming. Subsidies that producers consider essential to CO2 injection in the North Sea thus may come about.

A dilemma

Besides raising prospects for EOR tax breaks in the North Sea, DTI's study underscores strong governmental acceptance of a role for CO2 floods as tools of resistance to climate change. This creates a dilemma for environmental groups biased against oil.

"CCS would enable the continued use of fossil fuels, thereby giving a longer timeframe to achieve a transition to a fully sustainable energy system," DTI says in its study. Will environmental groups stand for anything less than the quickest possible rejection of oil?

The answer depends on whether they want mainly to limit CO2 emissions as a precaution against worst-case possibilities of unpredictable climate change, or whether they just want to engineer energy use in defiance of market forces and consumer preference. On this issue no less than any other, motive matters.