A counterintuitive notion: economic growth bolstered by high oil prices, strong oil demand

The standard comment that "high oil prices hurt economic growth" is totally undermined by real-world and real-economy trends.

Comparing oil and natural gas price averages in the US in late 1998 with price averages in late 2003, we find that crude oil import prices and bulk gas supply prices have risen more than 200%. Meanwhile, claimed economic growth of the US economy was running at more than 7% on an annual basis in late 2003.

It is therefore not difficult to argue that sharply rising oil and gas prices in fact increase economic growth rates, not the reverse.

Logically, low or suboptimal economic growth rates would tend to lower energy demand growth rates, which in turn would lower oil and gas prices. This has many "perverse," or apparently illogical, implications.

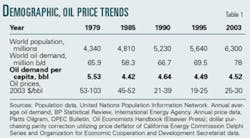

The worldwide economic mechanism that maintains oil demand growth at low levels when oil prices are low is complex and ramifying. The components of this simple fact of world economic history notably include the world average per capita, or "demographic," demand for oil, which reached its most recent peak when oil prices reached their most recent all-time high. In 1978 world average demand on a per capita basis was 5.5 bbl/year. Since the mid-1980s, it has been around 4.5 bbl/capita/year (bcy).

Because of this fact, any argument that higher oil prices—at least up to the point where they rise to perhaps $75-100/bbl—will or can result in a fall in world oil demand is doomed to failure when tested by real-world and real economic data. The major reason for "price inelasticity"—or in fact "reverse elasticity," which is demand tending to rise with rising prices—is that world economic growth tends to increase when oil prices rise.

Demographic demand, oil prices

World annual average demographic oil demand increased, regularly but erratically, through the 1970s, to a peak of a little more than 5.5 bcy in 1979 from about 4.7 bcy in 1970.

Since that time the demographic rate bottomed in the low oil price period of 1986-99 and has now started, slowly, to increase again. Table 1 shows how demographic demand has varied since 1979.

The term "oil shock" can have many meanings, but here we utilize what would be the essential element of the term: very large price changes in a short period of time.

On this basis, there have been at least four oil shocks since 1973—three upward price shocks (1973-74, 1979-81, and 1998-99) and one downward price shock (1985-86). None of these price shocks had an immediate, large impact on demographic demand.

The only price-elastic response that can be attributed to oil shocks would be the consistent (and large only in a cumulative sense) falls in demographic oil demand during 1980-85, with the demand rate of 4.42 bcy in 1985 being the lowest in the entire 1979-2003 period. Troubling still further the notion of a supposed price-elastic response or trigger for this fall is the fact that demographic oil demand had begun to decline by 1977-78.

Three essential points have to be mentioned. During 1973-79, after a 295% oil price rise in nominal terms through 1973-74, there was almost no effective reduction in the demographic demand rate. The price rise impact through 1973-74 can be called a "pause," rather than a major inflection or change of trend. After 1979-81, when oil prices briefly attained $103/bbl (in 2003 dollars), the decline in the demographic demand rate began to accelerate.

What is most notable, however, is that the demographic rate continued to decline after prices had fallen well below the highs of the 1979-81 period. As Table 1 shows, the 1995 demographic demand rate was almost unchanged from that of 1985, but oil prices had been more than halved in real terms. Perhaps most important to note is the third point: Since 1999, despite the "price shock" of 1998-99 (about 230% price rise in nominal terms), the demographic demand rate has continued to rise, if only slowly.

It is therefore unrealistic to affirm—and even harder to prove—that high oil prices (here defined as over $60/bbl in 2003 dollars) will or can have any immediate downward impact on world oil demand. Rather the converse: Higher prices tend to increase demand.

Higher oil prices' real impact

The real impact of higher oil prices, certainly up to the range of about $60/bbl, is to increase economic growth at the composite worldwide level.

This is the main reason why demographic oil demand during 1975, with oil prices at $40-65/bbl in 2003 dollars, was significantly higher than it is today. It should be clearly understood that if the demographic demand rate in 2003 was the same as in 1979, then world oil demand in 2003 would have been 95.4 million b/d. Relative to real total world oil demand at this time (about 78 million b/d), the additional capacity needed would be close to two times Saudi exports, more than three times Russia's export offer, or well above five times Venezuela's current export capacity.

There is no certainty at all that world oil supply would or could have been able to meet this demand.

Higher oil prices operate to stimulate first the world economy, outside the member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and then lead to increased growth inside the OECD. This is through the income, or revenue, effect on oil exporter countries, and then on metals, minerals, and agrocommodity exporter countries, most of them low income (per capita gross national product below $400/year). Almost all such countries have very high marginal propensity to consume. That is to say that any increase in revenues, due to prices of their export products increasing in line with the oil price, is very rapidly spent on purchasing manufactured goods and services of all kinds. During 1973-81, in which oil price rises before inflation were 405%, the New Industrial Countries (NICs) of that period—notably the so-called "Asian Tigers" Taiwan, South Korea, and Singapore—experienced very large and rapid increases in solvent demand for their export goods.

In easily described macroeconomic terms, the revenue effect of higher oil prices "greasing economic growth" was and is much stronger than the price effect on industrial producers.

NICs as a group or bloc of economies rapidly expanded their oil imports and increased their oil consumption as prices increased in 1974-81, because demand for their export goods had increased, due to the global economic impacts of higher oil and "real resource" prices. This has very strong implications for oil demand of today's emerging and giant NICs with large populations and immense internal markets: China, India, Brazil, Pakistan, and Iran.

For the much smaller NICs of 1975-85, their oil import trends during 1974-81 show dramatic growth only slightly impacted by the major price rises of the period. In general terms, the NICs Taiwan, South Korea, and Singapore increased their oil demand by about 60-80% in volume terms in this period of a 405% increase in nominal prices (Table 2).

Economic growth vital for future oil output

This macroeconomic mechanism of higher revenues for fast-spending poorer countries quickly levering up world economic growth (the very simplest type of Keynesianism, but at the global level) is rapidly and easily triggered by rising oil and other "real" resource prices.

This flatly contradicts the arguments by those who contend that higher oil prices "hurt poorer countries the most." What is more important is to consider how the investment need for assuring that future world oil, gas, coal and renewable energy supplies will be developed without higher oil prices and faster global economy growth.

Some idea of that need has recently been spelled out by ExxonMobil Corp. and by the International Energy Agency, which released its World Energy Investment Outlook report in November 2003, forecasting a need to spend an average of $103 billion/year for oil and $105 billion/year for gas through 2030. ExxonMobil has indicated (most recently in September 2003) that sustaining oil and gas production capacity itself requires the finding and development of 36 million b/d of replacement capacity by 2015.

Can this be done without higher oil prices? Higher revenues for many low-income oil exporter countries—notably for the special cases of Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and especially Iraq—may be the only short-term way to stop these countries from falling into civil strife, insurrection, or ethnic war, let alone making vast investments to maintain or expand their current export capacity. In the case of Iraq, increased oil revenues are a question of life or death because higher revenues might prevent the country from becoming ungovernable and might give it some potential for stability.

No immediate and instant recession can occur with oil at $50/bbl or even $60/bbl. Vastly higher oil prices than that would be needed to abort the worldwide mechanism of higher oil, energy, and real resource prices driving faster economic growth. Conversely, low oil and energy prices entraining low real resource prices, combined with rising population numbers, surely aggravate the cycle of poverty in low-income commodity exporter countries. Deprived of sufficient revenues, such countries can become "basket case" indebted countries, subjected to draconian conditions by the Club of Paris, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund for debt refinancing and restructuring. The ability and capacity for investing huge amounts of capital into oil, gas, and other energy production infrastructures by low-income, indebted countries is realistically very low or zero. Yet estimates for world investment needs of the oil and gas industry through the next 10-15 years extend into the range of several thousand billion dollars.

Without strong economic growth, it is unrealistic to expect that any "energy transition" can occur, for example, as predicated by the Kyoto Treaty on climate change. More critically, it also is unrealistic to expect that world oil supply can be increased at the rates required or as deemed feasible in such publications as the IEA's World Energy Outlook—that is a net average increase of about 2.25 million b/d/year during 2003-20 (raising capacity to about 115 million b/d), over and above replacement of capacity lost through depletion. These gigantic investment needs are very obviously dependent on strong and sustained economic growth. Without much higher and firmer oil prices, it is unlikely that global economic growth can be significantly increased from current low average annual rates for many key economies.

Demand shock

There is almost unlimited upward potential for world oil demand, and the price factor must be integrated in any forward analysis at the global or composite worldwide level.

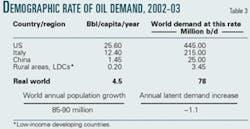

Current world oil demand trends range down from 25.6 bcy for the US to less than 0.2 bcy in rural areas of low-income developing countries (Table 3). While it is totally impossible that this could happen, the world's current 6.3 billion population consuming oil at US per capita rates would generate a demand of around 445 million b/d. At the other extreme, at 0.2 bcy world total oil demand would be telescoped to under 3.5 million b/d. The current 4.5 bcy world average is around one third the average in European Union countries but more than four times per capita average consumption in India and triple that of China—which soon will become the world's biggest industrial economy.

Annual increase of the world's population (which is continuing to fall as a percentage rate, and in absolute numbers) is now running at about 85-90 million. At a demographic demand rate of 4.5 bcy, the "latent" annual growth in world oil demand is itself about 1.1 million b/d, assuming no change in the energy economy, no fuel substitution, and no economic growth.

BP PLC's annual Statistical Review of World Energy in its 2003 edition notes the "surprising growth" of world energy demand since 2001 and 2002: about 2.6%/year compared with a so-called "10-year trend rate" of about 1.3%/year for oil alone.

Through 1975-79, with oil prices in today's dollars at $38-55/bbl, world oil demand growth easily achieved 4%/year, and most OECD countries achieved economic growth rates of about 3.75%/year on a real gross domestic product base. It is therefore easy to suggest the 10-year trend rate of 1.3% annual oil demand growth was an aberration—and that one of its determinants was cheap oil and gas during 1986-99.

Another was the continually falling rate of economic growth in the OECD countries, whose average annual economic growth rates fell by about 50% during 1975-95 and are now below 2%, on a real GDP basis.

The 10-year trend rate put forward by BP as having "surprisingly" disappeared in just the last few years was in fact already in the process of being replaced with a much higher rate during 1994-96, using BP data. As shown in Table 4, aggregate world oil demand trends changed from generally low, even negative (contraction) annual variations to consistently positive and often higher and firmer growth trends since, at the latest, 1994-96.

Restored or strengthened economic growth through oil price shock and due to the revenue and price effect of higher oil and energy prices also changes the type of growth towards more energy-intensive industrial and manufactured products and away from more service-based, less energy-intensive activities. This "perverse" factor itself increases oil intensity of world economic output and raises the "oil coefficient," or percentage increase in oil demand in proportion to percentage point growth in the economy for any country or region. Under a regime of higher oil and energy prices, world, regional, and national oil demand growth can therefore tend to be levered up. This, in turn, can then result in "surprisingly" firm demand for much more costly oil and gas.

Higher oil prices vs. future demand trends

Certainly one key reason for the recent jump in oil prices—and very much a more durable factor than headline war news—is that world oil demand growth is on a much higher track than apparent and superficial economic conditions would merit.

This especially concerns the OECD countries in many of which "surprising" oil and energy demand growth is taking place, for a large number of reasons. These include energy infrastructure renewal and replacement after many years of virtual negligence—that is to say, "catch-up" spending on maintaining and increasing energy supply systems. There also are economic and secular changes, which in combination produce increases in oil and energy intensity of economic output, after years of decline or no change.

On the supply side, despite large overhangs of surplus oil production capacity on paper, there is little or no physical and real surplus at this time, resulting in OPEC being easily able to maintain discipline. This was shown, in a negative way, by the extreme language utilized by a Wall Street Journal columnist on July 29, 2003, to qualify OPEC as "One Purely Evil Cartel" for deciding not to increase exports and thus enable oil prices to be talked down by the market.

The coming 4-5 years, in the absence of a major crash on world financial markets, will very likely see a continuation of this "demand shock," with growth rates well above 2%/year. About 2.25%/year could be considered the new paradigm, or longer-term trend.

It can be asked if oil demand stagnated through 2000-01 because of higher prices. More likely, this pause in growth was due not to oil price increases but simply to the severe, but slow contraction of equity numbers on all stock markets triggering an erratic and lengthy downturn in the real economy—but in no way changing the underlying trend of rising energy and oil intensity of economic activity. We have to note that global oil and energy demand growth from late 2002 and through 2003 continued on a 2-2.5%/year track—despite the supposedly "recession-wracked" economic conditions in several OECD economies—and at as much as 4-6%/year in much of the Asia-Pacific region.

This underscores the arguments of this article concerning the global economic mechanisms of energy price-triggered changes to the type and rate of economic growth.

One major reason for confidently projecting higher—but of course erratic—oil prices is as noted earlier: World oil per capita demand has almost unlimited upward potential, and higher oil prices themselves drive oil demand upward. It is no surprise, then, to find that the 10-year trend rate of 1.3%/year growth in world oil demand has almost certainly disappeared, as oil prices have responded to much more buoyant demand and have themselves generated faster economic growth, mostly outside the OECD bloc, that itself underpins world oil demand and therefore prices.

Understanding the mechanisms in play is vital to making accurate and realistic forecasts for future demand through the coming 4-5 years and beyond. This can be appreciated from Fig. 1 by comparing the actual trend rate of demand growth with official forecasts from elsewhere.

As Fig. 1 indicates, world oil demand can increase by as much as 7.5 million b/d in the next 54-60 months. By comparison, in the 72 month period of 1995-2001, world oil demand increased by only 6.7 million b/d (to 75.9 million b/d from 69.2 million b/d). Under these conditions of world demand growth, the "Iraqi wild card" becomes the most probable sentiment-shaping factor in future price trends—certainly through 2005-06. But real market supply determination will ever more depend on policies decided by, and events affecting, Russia and Saudi Arabia.

The unpreparedness in official circles relative to the demand shock discussed here can be judged by the fact that certainly until midyear 2003 (for example, the July 11, 2003, IEA monthly Oil Market Report), forecasts by many official sources for world oil demand by July 2004 were all limited to volume growth of no more than about 1 million b/d, raising world demand on an all-liquids basis to 79.08 million b/d by summer 2004.

This rate of average daily demand was already well exceeded by second half 2003. Furthermore, the growth rate applied (1.28%/year) is even less than that which BP still claims as the 10-year trend rate it contends applied during 1989-99 and should continue to apply, excluding "exceptional factors," notably growth of Chinese and Indian oil demand.

Under any scenario, it is very hard to understand why the No. 2 private oil corporation or the OECD's IEA would imagine that the rate of world oil demand growth should or could decline by nearly 50% in 1 year without massive economic recession.

The implications of underestimated growth combined with overoptimistic, and in fact fantasy, beliefs about how much oil Iraq can be forced or persuaded to produce and move to export terminals, together with very optimistic notions of Russia's capacity or willingness to continue increasing its export capacity, can be compared with any previous upward-price oil shock. That comparison entails supply reductions or cuts in the face of increasing demand.

The actual shortfall needed to enable upward price bidding to overcome the effects of all attempts to "inform" the market of large new supply potentials and possibilities is rather small: about 3-5%, or around 3.5 million b/d, through a few months.

On the basis of the growth trends shown in Fig. 1 and the persistent underestimates of demand growth by official and/or respected market analysts, the period in which prices can break out of the range below $35/bbl and increase to at least $50-60/bbl, is likely approaching very fast.

Observations

Cheap oil is seen by the decisionmaking elite in the richer nations as a necessary "passport" to economic growth. This is a pure fantasy. Only extreme oil prices (probably above $75-$100/bbl) will abort or cancel the global economy expansionary impacts of higher oil prices.

Since about 1995, demand shock has begun to operate in the world economy for a number of economic, social, or secular and technical reasons, leading to considerably higher underlying growth rates of world oil demand. Current demand trend growth rates for world energy and world oil are about 2.25%/year for oil and about 2.5%/year for energy.

Cheap oil and energy remain the essential base of conventional economic development and social progress anyplace in the world. This in turn is a powerful motor for continued and strong demand growth for fossil energy worldwide.

Upward potential for personal consumption of fossil fuels is essentially unlimited in this context.

Conventional or classic economic growth is enabled and facilitated at the world, or composite, level by oil prices rising to high levels. This also underpins, or even increases, world demand for fossil energy supplies, indicating that concerted international action is needed to plan for the effects of persistent underestimates of real demand growth trends.

The author

Andrew McKillop is an energy economist and journalist who recently edited a book on oil and gas depletion issues: The Final Energy Crisis (Pluto Press, London, September 2004). He has held a number of posts in national and international energy, economic, and administrative organizations and entities in Europe, Asia, and North America since 1975—among them the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries, Kuwait, Abu Dhabi, Papua New Guinea, Canada, British Columbia, the International Labor Organization, and the European Commission. A founding member of the Asian chapter of the International Association of Energy Economists, McKillop's most recent position involved conducting oil, gas, electric power, and coal policy analysis and energy conservation and renewables policy development and policy analysis for the EC. He also undertakes French-English technical, economic, financial, and business translation and is development manager for Sispeo.com, a Paris-based translation, marketing, and information electronic commerce business. McKillop has a BS in economics from the University of London and a diploma in cultural studies from Carlton University, Ottawa.