Shell's reserves revision: A critical look

Shell's downward revision of its worldwide reserves early this year created a big fuss among investors. Negative publicity surrounding the reserves revision forced the resignation of Shell's Chairman Sir Philip Watts and Vice-Chairman Walter van de Vijver.

The company is now reviewing its governance structure,1 and more senior-level management changes may be in the offing at this writing in late March. Reserves management procedures are also under review.

While part of Shell's reserves revision can be attributed to the inherent subjectivity in reserves booking, and is perhaps understandable, there appears to be little justification for most of the revision.

To the extent that the investors were misled, and their share prices on the stock market suffered, the investors' fury was well founded.

Nonetheless, Shell deserves credit for taking the initiative, albeit belatedly, to disclose the misstatement of reserves. Some of the "lost" reserves marked by revision have already been recovered, and the rest stand a high chance of being booked in coming years. Shell's reserves debacle has exposed an underlying industrywide problem in reserves booking.

Reshuffling of resources

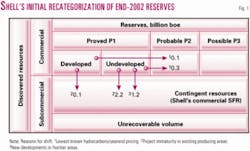

Shell first announced its reserves revision on Jan. 9, 2004, followed by some clarification on Feb. 5.2 A total of 3.9 billion boe of proved reserves, representing 20% of proved reserves booked with SEC (US Securities and Exchange Commission) as of Dec. 31, 2002, were reclassified into other categories of resources. Fig. 1 shows this initial reclassification based on data released by Shell.

In a subsequent announcement on Mar. 18, Shell reduced the end-2002 reserves by an additional 250 million boe.1 This brought the total end-2002 revision to 4.150 billion boe, or 21% of previously booked reserves.

Because little information was released on the later revision, it is not shown in Fig. 1. The Mar. 18 announcement also indicated a downward revision of end-2003 reserves (yet to be filed with SEC) by 220 million boe. The latest figures are preliminary. The total revision at present stands at 4.37 billion boe.

The terminology shown in Fig. 1 is that adopted by SPE, AAPG, and WPC (World Petroleum Congress). Contingent resources, in contrast to reserves, denote recoverable volumes from known accumulations that, under current conditions, do not fulfill the requirement of commerciality. This category is analogous to Shell's "Commercial Scope for Recovery" (SFR). Under SEC rules, only proved reserves are bookable.

From Fig. 1, the initial reserves revision involved:

A.2.3 billion boe in existing producing areas, e.g., Nigeria and Oman, moved to contingent resources due to concerns on "project maturity." Of this amount, 0.1 billion boe is developed reserves, and the other 2.2 billion boe is undeveloped.

B.1.2 billion boe in frontier areas, mainly in West Australia, Norway, and Kazakhstan, moved to contingent resources due to uncertainty with new developments. The reserves are undeveloped.

C.0.4 billion boe moved to probable reserves due to the LKH (lowest known hydrocarbons) limitation and yearend pricing. Of this amount, 0.1 billion boe is developed reserves and 0.3 billion boe undeveloped.

Thus, initially 3.5 billion boe was moved to contingent resources and 0.4 billion boe to probable reserves. Developed reserves, at 0.2 billion boe, comprised 5% of the total.

The additional 250 million boe revision (for end 2002) comprises largely proved undeveloped reserves in nonproducing fields, primarily in Northwest Europe and Australasia, presumably all offshore.

Shell did not disclose (and evidently had not at this writing decided) whether these reserves would be shifted to contingent resources or probable reserves.

Judging the revision

First to be noted is the fact that, although reserves estimates are dynamic and are subject to revision and reclassification as new information becomes available, Shell's reserves revision was not normal, in particular considering the size of revision. It represented retrospective debooking, which should have been avoided by greater attention to and stricter compliance with SEC rules at the outset.

Whether there were some mitigating circumstances for the revision depends largely on the circumstances under which the reserves were improperly booked in the first place.

According to some press reports,3 4 some 1.3-1.5 billion boe of debooked reserves are located in Nigeria, and the reports said Shell was reluctant to lower its Nigerian reserves for fear of damaging its business relationship with the government there and jeopardizing bonus payments it received as an incentive to add new reserves. Nigeria, which denied these reports, has different reserves booking rules than the SEC.

There also have been press reports that overstatement of the reserves may have been related to executive compensation at Shell—which issue, Shell has said recently,1 it is now addressing.

Clearly, to the extent these allegations are true, Shell's overstatement of its reserves vis-à-vis SEC cannot be condoned.

Putting these issues aside, Shell's reserves revision has also exposed a fundamental problem with reserves booking: the judgmental aspect. SEC rules, arguably with good reason, are not clear cut and are subject to interpretation.

It is possible for different estimators or auditors to interpret compliance with SEC rules differently, and assessing compliance with SEC rules is basically a call for judgment.

This is an industrywide problem, and Shell, quite unintentionally it seems, has brought this problem to the forefront. In this respect, Shell can claim a measure of mitigating circumstances in its reserves revision.

To give an example, a key SEC requirement for resources to be classified as proved reserves is the presence of "reasonable certainty" that the resources under consideration will be recovered under existing economic and operating conditions.5 This is an ambiguous requirement, and not everyone can agree on what is "reasonable certainty."

A decision as to compliance must take into account not only technical uncertainties and technology but also prices, costs, contractual milestones, transportation and marketing arrangements, ownership and/or entitlement terms, and regulatory requirements.

Thus an assessment of both volumetric uncertainty and economic risk is involved. This entails a good deal of judgment.

SEC has not issued a particular confidence level for booked reserves, though it refers to SPE's requirement that there be at least 90% confidence for proved reserves when probabilistic methods are used for reserves determination.

Investors can also find a measure of solace in the fact that Shell's reserves revision was not prompted by errors in reserves calculation. The estimated volumes remain unchanged, except that some are now recategorized. Furthermore, ultimate recoveries associated with debooked reserves will in all likelihood remain unaffected.

Another mitigating factor is that only a small portion of reclassified reserves were in the developed subcategory. This means relatively small adverse effect on future net earnings.

On the downside, one obvious effect of the reserves revision was loss of credibility at Shell's top management. For a company that projects a conservative image, loss of credibility is a serious blow. An immediate negative consequence was a sharp decline in the company's share prices in the stock market, resulting in big losses for the stockholders.

On a longer term basis, a more serious setback for investors will be a likely delay in production of some of the recategorized reserves. It is difficult to judge the extent of delay, but a negative impact on investors' returns seems unavoidable.

On long term, investors may also assign a higher equity risk-premium to E&P shares in general,6 affecting the market.

Shell has estimated that its initial reserves reclassification translates into a 10% reduction in the standardized measure of discounted future cash flows as disclosed to SEC. This is less than the 20% reduction in proved reserves, as the large majority of reclassified reserves are undeveloped. On the other hand, and as Shell points out, due to premises used in calculations, e.g., yearend oil prices, the standardized measure does not provide a realistic estimate of future cash flows from proved reserves.

A closer look

Looking at the details of initial reserves revision, reclassification of 2.3 billion boe of booked reserves in existing producing areas (Shell's "heartlands") into the contingent category (footnote 2 in Fig. 1) is undoubtedly the most difficult-to-understand aspect of revision.

According to Shell, reclassification was prompted by concerns regarding "project maturity." The company has not clarified what this term specifically means. It may refer to lack of commitment to project development for reasons such as lack of host government support, change in capital spending priorities, etc. It may also refer to aggressive booking linked to technical uncertainties, e.g., booking presence or downdip limit of hydrocarbons based on seismic without adequate well control. For reserves downgraded in Nigeria, this is probably the likely reason.

While Shell has not made the distinction, the additional 250 million boe revision announced on Mar. 18 for end 2002 appears to be also a "heartland" problem associated with project maturity.

Reclassification of 1.2 billion boe of booked reserves in frontier areas into the contingent category (footnote 3 in Fig. 1) seems much less serious. The main fields containing these resources are Ormen Lange gas field in the North Sea off Norway, Gorgon gas field off Western Australia, and Kashagan oil field in the Caspian Sea off Kazakhstan. These are undeveloped fields.

Remote locations, harsh and environmentally sensitive operating conditions, and unsecured market positions (for gas) obviously posed challenges to development of these fields. The reclassification was prompted by lack of development commitments as of end 2002.

It needs to be noted, however, that due to agreements signed in 2003 and 2004, Ormen Lange and Kashagan development commitments are now in place,7 and reserves for these fields will be rebooked in 2003 and 2004, respectively. Negotiations to proceed with Gorgon development—where ChevronTexaco is the operator—are also at an advanced stage, and Gorgon reserves may well be booked in 2004 or 2005.

Thus for investors, debooking of 1.2 boe of reserves in frontier areas should not be as serious a setback as it first appears.

Reclassification of 0.4 billion boe of proved reserves into the probable category (footnote 1 in Fig. 1) also appears not to be a serious breach of investor confidence. One reason for debooking was lack of well penetration data for fluid contacts. In such situations, it is an established procedure in the industry to use pressure data (if consistent) to extrapolate fluid contacts below LKH in the reservoir. Shell must have had such pressure data. But under strict SEC rules, resource volumes below LKH, if not penetrated in well, are not bookable.

The other reason for this type of debooking was cost-oil adjustment for yearend oil prices as called for in production sharing contracts, with high prices leading to reduction in cost-oil entitlement—and in bookable reserves. This is effectively an accounting adjustment and probably could not have been foreseen at the time of booking. When yearend oil prices are low, bookable reserves would increase, providing a compensatory effect.

Lastly, it is not readily clear why Shell reclassified a large portion of debooked reserves into the contingent category (Fig. 1). In consideration of commerciality (e.g., Kashagan declared commercial by partners already in 2002), some of these resources could have been placed in the probable reserves category. This would not have affected the volume of debooked reserves, but it would have taken away some of the psychological sting of recategorization. Probable reserves imply a higher degree of confidence and investor comfort than contingent resources.

Furthermore, Shell appears to have been too conservative in debooking Kashagan reserves (380 million bbl for first-phase development). In 2002, there was arguably "reasonable certainty" that this supergiant field, thought to contain 11-13 billion bbl of ultimately recoverable oil, would be commercially developed. Plans were already under way to bring the field onstream in 2005 (now postponed to 2008). In this context, one wonders how other Kashagan partners treated this field's reserves. One partner, Total, apparently booked Kashagan reserves in 2002 and does not intend to debook.8

Ormen Lange field also highlights differences among partners for treating reserves. Shell had initially booked 109 million boe for this field, which was debooked by the Jan. 9 and Feb. 5 announcements. The intention was to book Ormen Lange reserves to the tune of 256 million boe for 2003.

The company's Mar. 18 announcement, however, indicated that, due to too-aggressive use of seismic data earlier, only 90 million boe would be booked for 2003. Two other partners for Ormen Lange, BP and Norsk Hydro, appear to have booked roughly 4 times more reserves per unit equity.9 A fourth partner, Statoil, on the other hand, was evidently on par with Shell as far as reserves booking.

The larger issue

Shell's reserves revision has exposed a fundamental problem in the E&P sector: reliability or consistency of booked reserves.

Setting aside any possible deliberate act, Shell's reserves debacle seems to be rooted at least partly in the subjectivity of the reserves booking process. While some companies, since Shell first announced its reserves revision, have come forward to express or imply their differences with Shell on the question of booking reserves, others have steadfastly claimed their bookings were proper and not subject to revision.

The fact is, without a thorough, independent audit, no company can claim a high ground on reserves booking.

Reserves revisions by a suite of independents,6 e.g., El Paso, after Shell's initial reserves announcement indicates that further restatement of reserves in the sector could be in the making. A tightened enforcement of SEC rules and guidelines could prompt more companies to restate reserves.

Reserves booking is an intricate process that involves: (a) reserves estimation and (b) reserves classification.

SEC rules do not prescribe how to estimate reserves. They only prescribe what reserves are bookable, and some of the issues in this connection are discussed elsewhere in this publication.10 Reserves estimation is much more of a daunting job than is reserves classification, but both involve considerable subjectivity.

This is where the interpretive and judgmental aspects come in that could cause different estimators to come up with different bookings based on the same data.

Industry representatives tried to resolve some of the interpretive differences in reserves booking with SEC engineers, but little consensus between the two sides emerged.11

What is the solution? It has been suggested8 that a standardized approach should be devised to estimate reserves. While a standardized approach would bring a degree of uniformity to reserves estimation and would facilitate the audit process, it is highly doubtful whether it would give more accurate results.

The industry's track record of correctly estimating reserves, in particular at the pre-production stage, is dismal12 13 (and so, it is not surprising that most of Shell's recategorized reserves pertain to undeveloped fields), and this is partly due to inadequacy of commonly used reserves estimation methods.

Errors associated with dependencies and aggregation of reserves, for example, may creep in unsuspected during reserves estimation. These errors have the potential to be more severe with majors that lump reserves from different reservoirs in different fields in different countries.

Furthermore, it would be impractical to write and follow strict reserves estimation guidelines to cover a bewilderingly large number of possibilities. Reserves estimation is fraught with inherent uncertainties, and no amount of standardization will remove subjectivity from the process.

Certification of reserves estimators14 would help and would bring a higher degree of public confidence to booked reserves. There also should be clearer guidelines, better training, peer reviews, and other internal controls within companies.

In the final analysis, however, reliability of reserves estimation much depends on the experience, competence, and integrity of the estimator.

Regarding reserves booking, the author feels that SEC's reserves definitions and guidelines, in concert with those of SPE, are adequate and necessary to protect investors' interests. Judgment necessarily plays a role in reserves booking.

If there is one valid criticism of SEC, it is that proved reserves do not allow the investor to get a fuller picture of a company's reserves strength. Reporting of probable and even possible reserves along with proved reserves, as is now being done in Canada,10 would largely alleviate this problem.

An alternative is to report the expectation or mean value of reserves in addition to proved reserves. For in most instances, it is the expectation of reserves, not the proved values, that are used in project screening in field development. Only risk-averse companies use proved reserves for screening, and they are rarely the ones that realize significant economic returns.

Conclusion

While Shell can show little justification for overstating its reserves, the problem it has raised is not unique to Shell. Setting aside improper conduct, there exists an industrywide problem rooted in the subjectivity of reserves booking.

For investors, some adverse effects from Shell's reserves revision are unavoidable; but on a longer term the downside appears to be less than gleaned from first indications. In some respects, Shell seems to have been overcautious in its reserves recategorization.

Shell is currently under investigation by the SEC and the US Justice Department. Interestingly, most of Shell's ill-fated reserves were booked before 2001, when the sacked chairman and his deputy assumed their positions.

References

1. Royal Dutch/Shell media release, Mar. 18, 2004.

2. Royal Dutch/Shell media releases, Jan. 9 and Feb. 5, 2004.

3. New York Times, Mar. 19, 2004.

4. Reuters News Service, Lagos, Mar. 21, 2003.

5. SEC oil and gas reporting rules and guidelines, e.g., July 25, 2000; Mar. 31, 2001.

6. OGJ, Mar. 22, 2004.

7. OGJ, Dec. 23, 2002, Aug. 25, 2003, Oct. 7, 2003, and Feb. 25, 2004.

8. Comments by Total CEO Thierry Desmarest, Times Online, London, Feb. 21, 2004.

9. Reuters News Service, London/Oslo, Mar. 19, 2004.

10. Reporting and various commentaries in OGJ, Jan. 19 and Feb. 2, 2004.

11. Harrell, D.R., and Gardner, T.L., "SEC, Industry Discussion Illuminates Reserves Reporting Issues," OGJ, June 23, 2003.

12. Demirmen, F., "Reliability and Uncertainty Assessment of Field Reserves: A Dismal Industry Record and How We Can Improve," abs., AAPG Annual Convention, San Antonio, April 1999.

13. Demirmen, F., "Reliability and Uncertainty in Reserves: How the Industry Fails, and a Vision for Improvement," abs., Landmark City Forum, Houston, April 2002.

14. Harrell, D., "The Time Has Come to Certify Reserves Evaluators," OGJ, Mar. 15, 2004.

The author

Ferruh Demirmen (ferruh@ demirmen.com) is an independent petroleum consultant in Houston. He has 36 years of international experience on the E&P side of the oil industry. He retired from Shell Internationale Petroleum Mij. in 1994 and currently deals with reserves evaluation, subsurface risk mitigation, and developments in Iraq and Turkey. He holds a PhD in geology from Stanford University.