Large US independent petroleum firms emerging as viable competitors to majors

A group of the 10 biggest independent US petroleum companies has emerged as viable competitors to the world's major oil and natural gas firms.

The aim of this article is to identify the main features and assess the growing significance of these companies on the world oil and gas scene.

Comprising the group are Amerada Hess Corp., Anadarko Petroleum Corp., Apache Corp., Burlington Resources Inc., Devon Energy Corp., Kerr-McGee Corp., Marathon Oil Corp., Occidental Petroleum Corp., Unocal Corp., and Valero Energy Corp.

These companies are primarily active upstream, and their gas dimension is sometimes very significant, higher than the majors in relative value. These firms are experiencing growing globalization, generally focused on a few key areas.

Like the majors, they have adopted a dynamic external growth strategy, giving rise to significant increases in size. The analysis of their activities shows that these companies are full-fledged players, exercising the function of operator in many cases and relying on leading-edge technologies.

Few of these companies are integrated, and the existence of large independents downstream is possible but rare. The financial results of 2000-01 were exceptionally good, while those of 2002 are expected to register as a slump, due particularly to the weakness of gas prices in the US.

Measured by the yardstick of market capitalization, the 10 foremost oil companies worldwide, before the most recent mergers, were ExxonMobil Corp., Royal Dutch/Shell Group, BP PLC, TotalFinaElf SA, Chevron Corp., ENI SA, Texaco Inc., Repsol-YPF SA, Conoco Inc., and Phillips Petroleum Corp.1 For this analysis, we shall refer to these companies as majors, insofar as they are very big, integrated, and international.

Market capitalization also was the criterion by which we picked the 10 big independents for this analysis.2 These companies are active primarily in North America and represent players of significant size in this region. Their combined oil and gas reserves in 2001 amounted to five times those of Conoco and two and a half times those of Phillips. Note, however, that our analysis covers only a small part of the US and Canadian petroleum industry, insofar as this industry includes dozens of other smaller companies, attesting to the vitality of the oil and gas sector in this part of the world.

In fact, although US oil imports are higher than the production of Saudi Arabia, the US in 2001 was the world's No. 2 oil producer and No. 1 natural gas producer,3 and petroleum activity there is still very intense.

Presentation of the sample

Most of the companies examined here are old—some formed in the 19th century—and have participated in the US and international petroleum history.

The spectrum of their current activities accordingly stems from a long history, as well as the occasional more or less recent abandonment of areas deemed nonstrategic. The strong competitive environment of the last 15 years has led to drastic reassessments of the quality of assets and has led to major repositionings. For example, Unocal, which, shortly after having filed patents for the manufacture of reformulated gasolines—still today the subject of numerous legal battles in the US courts—decided in 1997 to sell its downstream division to Tosco4 Corp. in order to focus on the upstream oil and gas industry.

The 10 companies of our sample are not all, like the majors, integrated companies. Some of them have decided to be present only in a single sector and to develop a strategy of concentration. These include Anadarko, Apache, Burlington, Devon, and Unocal, which are active only upstream, and Valero, which focuses exclusively downstream. Others, such as Amerada Hess and Marathon, are both producers and refiners, while Kerr-McGee and Occidental also have chemical assets,5 in addition to exploration and production. However, upstream activity is generally predominant. Thus, for example, the distribution of capital employed by Amerada Hess in 2001 favors E&P, with more than 70% of its investments devoted to this segment.

Besides, some companies have activities downstream in the gas chain and sometimes produce electricity by cogeneration. Nine out of 10 of the companies covered in this article have a mainly upstream positioning; to varying degrees, these produce both oil and natural gas.

Independents vs. majors

If we compare the smallest of the current majors, ConocoPhillips, with the biggest independent, Anadarko, in terms of reserves and production and with Occidental in terms of net incomes, a large difference in size exists between them, as can be expected.

The reserves of ConocoPhillips amount to three and a half times the reserves of Anadarko and nearly three times its production. In terms of net income, Occidental, the independent with the biggest earnings in 2001, logged income that was a third the size of ConocoPhillips's. In terms of market capitalization, in May 2002, Anadarko's market cap was a third the size of ConocoPhillips's.

This leads us first to analyze the features of the nine companies currently active upstream. The world's leading eight oil firms (from ExxonMobil to ConocoPhillips) are primarily oil companies, although the proportion of natural gas in total oil and gas production is close to 50% for some of them. The same cannot be said of several companies of our sample, which are primarily gas companies.

Figs. 1 and 2 demonstrate that this is clearly the case for Burlington and Unocal, as well as Anadarko, Devon, and Apache to a lesser degree.

Global shift

A limited level of globalization, with an activity base strongly focused on North America, is a feature traditionally associated with the independents, although historically speaking, some of these companies have made significant discoveries outside North America (Occidental in Libya and Colombia, Unocal in Thailand).

However, some companies have oil and gas reserves located mainly outside North America (Amerada Hess, Unocal), and the general ongoing international orientation is clear if we consider the distribution of production zones (Table 1).

Amerada Hess, Kerr-McGee, and Unocal produce at least 40% of their oil and gas outside North America. The weight of oil production outside North America is significant for nearly all the companies,6 representing values of 20-75%.

Contrary to the status of the majors, which produce in a large number of countries, these companies have most of their international production in a given area: the North Sea for Amerada Hess (11 million tonnes of oil equivalent, or toe, per year, or 50% of the total company production) and Kerr-McGee (5 million toe/year, or nearly 40% of the total produced), Algeria for Anadarko (1.1 million toe/year, or a third of its international production), again attesting to the concentration strategy.

Only Occidental has a more diversified portfolio of activities (Qatar, Yemen, Russia, Colombia, Ecuador, Oman, Pakistan), but the quantities produced are generally small by country.

Because natural gas is an energy supply that is more difficult to market, the independents are less active abroad in this sector: Amerada Hess and Unocal, respectively, in the North Sea (4 bcm/year) and the Far East (8.5 bcm/year) are the two main players in this area. The globalization of the independents is hence quite genuine and would be even more evident if we analyze the areas where they conduct exploration activities, foreshadowing future production.

Full-fledged players

The independents are not just minority partners, leaving operatorship to the majors. Thus it is not rare to find independents in charge of operations (Unocal in Thailand, Occidental in Colombia).

Some companies also specialize in very technology-intensive niches, such as the deep water (Kerr-McGee is the operator of Neptune and Baldpate, US Gulf of Mexico fields located in more than 1,650 ft of water), the resuscitation of production in old fields through enhanced recovery (Occidental, Amerada) and natural gas from coal mines (Devon, Marathon).

Another illustration of these companies' growing stature is the participation of Occidental and Marathon in one of the natural gas consortiums in Saudi Arabia (Core Venture No.2).

Beyond their upstream weighting, it also appears that these 10 companies, while they may not have the world scale of the 10 majors, represent significant competitors in the areas of activity where they concentrate. This illustrates the relevance of the niche strategy that they have adopted and the name of superindependents that they are sometimes given.

Few independents are integrated

Although the group of 10 biggest US independents displays a strong upstream orientation, some of them are nonetheless involved in the downstream sector: Amerada Hess, Marathon, and Valero.

Thus with seven refineries, Marathon Ashland Petroleum (62% controlled by Marathon) accounts for nearly 6% of US refining capacity. Valero controls 12 refineries, while Amerada Hess has a smaller presence, since it holds interests in only two refineries (a 50% stake in the Hovensa complex in the US Virgin Islands and the Port Reading catalytic cracker in New Jersey). A look at their respective levels of crude oil production and refinery throughput shows that Valero and Marathon are exclusively or chiefly downstream companies, while Amerada Hess has a balanced structure.

Kerr-McGee, wishing to focus on its key areas, sold its refining and coal-related assets in the 1990s but retained the proprietary chemicals segment (pigments), which contributed in 2000 to about 10% of income from operations (7% in 2001). The same applies to Occidental, which has a significant chemical branch, focused on the vinyl chloride chain.

Moreover, some of the companies are integrating in different areas of the energy value chain: the presence in the gas logistics (midstream) and in the downstream gas sector through the installation of power generation and marketing structures, particularly by cogeneration. Thus Marathon recently acquired Enron Corp.'s delivery rights at the regasification terminal of Elba Island, Ga., and seeks to promote the installation of a gas pipeline from Norway to the UK.

Valero is the only company in this group that has specialized exclusively in refining and marketing. Its refineries in Texas, Louisiana, New Jersey, Oklahoma, Colorado, California, and Canada have a combined capacity of nearly 2 million b/d, and the company owns a marketing network spread over 34 states and Canada. Its refining capability is highly sophisticated, with considerable operational flexibility enabling it to process a whole range of heavy feedstocks and convert them to gasolines and diesels meeting the most stringent specifications, such as those of the California Air Resources Board. Valero has adopted a strategy of concentration—selling its natural gas business in 1996 for $1.5 billion—and intense external growth: Five years ago, it had only a single, 170,000 b/d refinery.

In 2001, moreover, Valero virtually doubled in size, following its acquisition of Ultramar Diamond Shamrock. Yet it is still the smallest company of our sample. Hence it appears more difficult for an independent to grow and survive downstream than upstream. It is very likely that the huge investments needed to manufacture high-grade products demanded by the US market penalize or jeopardize the existence of smaller companies in this sector. Besides, the margins are often narrow, and the rates of return on capital employed are generally much lower downstream than upstream.

Dynamic external growth strategy

The optimization of activity portfolios accordingly represents a significant concern of the independents. Thanks to abundant financial resources, large-scale projects have been completed, leading to major reinforcements: a doubling in size for Anadarko and sharp growth of Occidental in California and Texas, for example.

Most of the acquisitions listed in Table 2 illustrate the quest for reinforcement in areas where the companies are already active (North America) in order to benefit from new synergies, to spread fixed costs over a broader base, and to achieve critical size in certain regions. The possibility of acquiring assets that the majors abandon—for reasons of streamlining or because they are forced to do so in the US by the Federal Trade Commission—and the attraction of Canada as a natural area for expansion and growth, explain the numerous acquisitions of onshore reserves and refining assets.

Furthermore, since the number of interesting companies likely to be acquired is shrinking, the competition among the various players has led to a rapid succession of mergers and acquisitions. This was especially true in 2000 and early 2001 insofar as, thanks to the high prices of oil and natural gas, the financial situation of the companies was excellent, and many transactions were conducted not by trading shares but by cash outflows (Devon, Marathon in 2001). The many acquisitions should not obscure the fact that the amounts involved are large, often several billion dollars, representing large-scale operations for these companies.

It is also important to note that many disinvestments have taken place, in order to focus on the most promising assets and to release liquidities designed to minimize debt. Thus at their scale and in their field of activity, the independents appear to display the same behavior as the majors, in their wish for external growth and optimization of activities. Yet the financing of these mergers and acquisitions generally leads to a much higher debt level for the independents than for the majors.

Developments in reserves

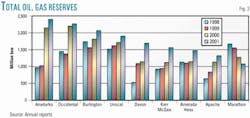

These overall acquisitions explain a good part of the growth in reserves of the companies in this analysis (Fig. 3). With the exception of Marathon, all the companies have increased their reserves very significantly in 4 years (threefold increase for Devon, doubling for Anadarko and Apache).

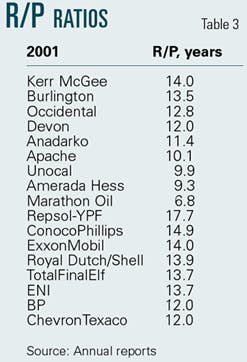

Table 3 shows the anticipated life span of the proved oil and gas reserves of the companies examined, at the present rate of production, and compares them with those of the majors. If we don't consider the specific cases of Repsol-YPF and Marathon, the R/P ratio of the majors generally is 12-15 years, while that of the independents displays a wider dispersion at 9-14 years.

Despite the sharp increases, the independent companies of our sample hence possess smaller proved oil and gas reserves than the majors, not only in absolute terms, but also generally in terms of life span.7

2001 Results

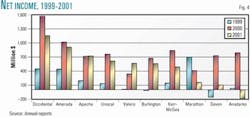

Financial results for 2000 and 2001 for the independents were exceptionally good.

In 2000, the companies benefited from the high prices of oil and natural gas, as well as higher refining margins for the companies active downstream. Prices fell in 2001, affecting the performance of certain companies.

However, the increases in production often helped to offset the price effect. Thus the results for 2001 for our group of independents are often comparable to those of 2000, despite the 15% drop in oil prices from the year before and in the 20% decline in gas prices in the US.

The rise in production in 2001, often associated with mergers and acquisitions, of Amerada Hess (+16%), Anadarko (+78%), Apache (+32%), Devon (+12%), and Unocal (+8 %) explain the trend in the results of these companies. The price-hedging operations of some of these companies conducted on forward markets also diminished the impact of the lower prices.

The comparison of results between companies must nonetheless be made with caution, insofar as the accounting methods employed are not always rigorously comparable. Two methods of accounting for exploration expenditures and (dry development wells) exist in particular and are accepted by the US Securities and Exchange Commission: the successful-efforts method and the full-cost method. The former considers geology, geophysics, and dry well expenditures as expenses, while successful wells are capitalized and depreciated according to their production rates. By contrast, with the full-cost method, all exploration expenditures (geology, geophysics, and drilling) are capitalized and depreciated. Both approaches are justified. The first naturally treats as expenses any unsuccessful exploration, which effectively has no value for the future.

The second amounts to interpreting the entire exploration activity as an investment that must therefore be depreciated. Anadarko, Apache, and Devon use the full-cost method. while Amerada Hess, Burlington, Kerr-McGee, Marathon, Occidental, and Unocal employ the successful-efforts method.

Moreover, depending on the conditions in which a merger is completed, it was possible, until June 30, 2001, to consider the transaction from an accounting standpoint as a pooling of interests or as an acquisition (purchase method). We saw earlier that the independents completed several mergers and acquisitions in recent years, and these differences in accounting make comparisons difficult over several years and could require retreatment, in order to make a detailed analysis of performance. US accounting authorities now require all mergers of operations to be considered as acquisitions (Statements of Financial Accounting Standards No. 141), which will introduce more uniformity in the presentation of the financial statements.

Fig. 4 shows that Occidental was the leading independent in terms of net earnings during 1999-2001. In 2001, Occidental's chemical operations posted a loss, so its entire profit that year was derived from its upstream activities. Through its size and the variety of countries where it produces, the company resembles the majors, but it retains a feature of the independents, namely its very strong US involvement (60% of its oil and gas production). Occidental's good performance is explained by a sharp growth in its upstream operations earnings (associated partly with the acquisition of Altura Energy Ltd., which significantly boosted its oil production in the US).

For reasons of an accounting nature, net income figures can be dramatically affected by the short-term volatility of oil and gas prices. In fact, at the end of each quarter, the companies have to evaluate their oil and gas reserves using the price on the last day of the quarter. If the discounted value of future production is lower than the accounting value of the assets, a provision must be set aside for depreciation (impairments). This is an exceptional nondisbursable accounting expense that has no impact on cash flow but reduces net income. The latter may therefore not faithfully represent the performance for the year.

In 2001, this was the case for Anadarko, which posted an accounting loss of $188 million vs. net income of $1.389 billion without this provision, and for Devon, whose net income in 2001 dropped sharply for the same reason. These two companies, as we showed earlier, made acquisitions in recent years and valorized them in their books in accordance with accounting rules by using "fair value" of the reserves estimated on the basis of price forecasts that the management considers realistic over the medium term. Due to sharp recent fluctuations, the closing prices of certain quarters in 2001 were substantially lower than the values employed and hence led to the setting aside of these provisions. It is conceivable that, in a context of high price volatility, with depressed or exaggeratedly high prices, this accounting necessity could affect the faithful image of the accounts, leading to an underestimation of the value of the company's reserves.

In terms of performance and excluding special items, the No. 2 company in the group is Anadarko, a company that has slightly bigger oil and gas reserves than Occidental.

Also, through its external growth strategy and efforts to accelerate production of its reserves, Anadarko has the largest oil and gas production (27 million toe/year) of our sample, followed by Unocal and Occidental.

Marathon recorded exceptional expenses in 2001 associated with the separation of parent USX Corp.'s oil and steel businesses.

Without these one-time items, Marathon would have been the third-ranked company in terms of results, thanks in particular to the excellent contribution from refining-marketing (about 50% of income from operations).

The only downstream independent of our sample, Valero, also significantly increased its profits, while the two mainly gas companies Unocal and Burlington Resources were affected by the drop in North American gas prices.

Market capitalization

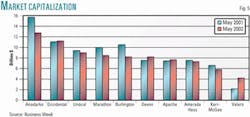

Our sample consists of the 10 US companies trailing the (now) 8 international majors, according to the yardstick of market capitalization.

The world contains many other oil companies that are bigger in terms of market cap but that are in some cases fully or mainly owned by public capital and are not listed on stock exchanges. Some public companies have part of their capital listed, and their market value is estimated by publications such as Business Week and London's Financial Times. Considering the companies selected by these two publications and the private non-US companies, the following companies and their estimated market cap in billions of dollars, can be added between the 8 majors and the 10 independents in our sampling:8 Petroleo Brasileiro SA (27), Statoil ASA (18.9), OAO Yukos (18.7), OAO Gazprom (17.4), BG Group (15.3), EnCana Corp. (14.7), and Norsk Hydro ASA (13.4). Anadarko Petroleum, the first company of our sample, then falls to 16th position in terms of market capitalization worldwide, but it is clear that this type of classification has its limits with regard to the evaluation of certain companies (for example, Gazprom), which is sharply biased by the fact that their floating capital (listed on the stock exchange) is very limited.

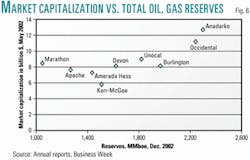

The drop in crude prices in second half 2001 reduced the market values but did not change the overall rankings. Anadarko thus takes first place in terms of market value, trailed far behind by Occidental in second place (Fig. 5).

Fig. 6 shows the positions of the nine companies active upstream. It clearly shows a group of independents bunched together (Apache, Amerada, Kerr-McGee, Devon) with a significant difference in reserves from the more gas-intensive companies of our sample (Burlington in the US, Unocal in Southeast Asia) and two companies that stand out sharply: Anadarko and Occidental. Marathon stands slightly apart due to its smaller reserves, with a market capitalization that results from its deep engagement in refining and distribution.

2002 results

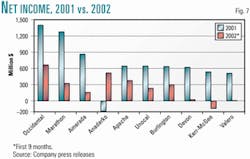

Performance of the independents group in 2002 fell below that of 2001, due to the low prices at the start of the year (Fig. 7). Crude prices rose during the year, while natural gas prices remained substantially below their 2001 levels.

The companies present in the refining sector (Amerada Hess, Marathon, Valero) have suffered from small refining margins. Some exceptional expenses (associated with the depreciation of assets as impairments) also tended to reduce the net income of Amerada Hess, Devon, and Kerr-McGee.

So due to a less favorable price and margin environment, the financial results of our sampling of companies were likely to be slightly lower in 2002, following 2 exceptional years. The companies generally hoped for a recovery of natural gas prices in the US to stimulate their results in the coming years.

Their performance in 2003 will also obviously depend on the price of crude, which is at a relatively high level today due to international pressures. This level is not necessarily sustainable over the long term, but the invasion of Iraq, if it materializes, could bring new pressures to bear on short-term prices.

Conclusion

This analysis of the 10 largest independent US petroleum companies clearly illustrates their importance in the global petroleum market.

Even if these companies are significantly smaller than the majors, they are large enough—and specialized enough— to be significant players in the segments on which they have chosen to focus.

In contrast to the majors, which seek to be world leaders in their core business, these companies generally concentrate on a narrower range of activities in a smaller number of countries. As we have seen with these companies, the upstream oil and gas sector is generally very favored, with a strong base in the US but with an openness toward the international scene that is rapidly expanding for some companies.

This strategy of targeting certain sectors of the market or certain geographic locations gives independent companies the critical mass necessary to be profitable and competitive directly with the majors. These independents can thus offer host countries a credible alternative to the major companies. They also offer the possibility to monetize some acreage in areas geopolitically or politically too risky or too mature to interest the largest companies, which, given their size and visibility, could have higher structural costs or may not wish to be present in certain politically controversial countries.

The growth strategy of these large independent companies is similar to that of the majors and usually relies on permanent optimization of their assets and identification of opportunities for external growth. Many of these companies have grown significantly in the last few years, making them less vulnerable to hostile takeover.

Independents thus have many characteristics in common with the majors. However, the independents have carved out noteworthy niche markets, assuring them a distinct role in the oil and gas world, contributing to the diversity of its players, and sustaining a high level of competition. Their flexibility is the gauge of their sustainability in a constantly changing environment.

References

1. These companies were discussed in a previous article, published in September 2001 in Cahiers de l'Economie, No. 46, Institut Français du Pétrole.

2. In fact, the 10th US independent company by market capitalization is EOG Resources Inc. and not Valero Energy. We nonetheless decided to select Valero for its downstream positioning and its merger with Ultramar Diamond Shamrock Corp., which will lead to a significant increase in its size. EOG Resources is active only upstream.

3. BP Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2002.

4. The same Tosco was acquired by Phillips in 2000, demonstrating the constant recomposition of the American petroleum landscape.

5. Kerr-McGee's chemical operations are in fact almost exclusively concerned with the production of a specific product, titanium dioxide, which is a base for pigments. Kerr-McGee is the world's third biggest producer of titanium dioxide.

6. With the exception of Burlington Resources, which is nearly exclusively a gas company tightly focused on North America.

7. Some companies have abnormally high or low figures for the life of their reserves, due to the opposing variations during the year in the level of their reserves and their production. This applies in particular to Repsol-YPF, which registered a 20% increase in its reserves in 2001 with a concomitant drop of 3% in its production. Marathon registered a drop in its reserves over the last 4 years, explaining its low R/P ratio.

8. Market capitalization as of Apr. 1, 2002, according to Business Week, for Statoil, BG Group, EnCana, and Norsk Hydro. Market capitalization as of Jan. 1, 2002, according to Financial Times for Petrobras, Yukos, Gazprom.

The authors

Jean-Philippe Cueille is director of studies at the Center for Economics and Management at the IFP (Institut Français du Pètrole) School. He is a chemical engineer with an MS in economic and corporate management from the IFP School—a program he currently manages. Prior to that, Cueille was in charge of the petroleum economics and management program organized jointly with the Colorado School of Mines, Texas A&M University, and the IFP School. Before that, he conducted seminars on petroleum economics at various oil companies.

Luis de Castro Pinto Coutinho has a degree in mechanical engineering from Instituto Superior Técnico, Lisbon, and an MS in economics and corporate management from the IFP School. He is a former consultant for Accenture, where he held responsibilities in the customer relationship management service.

Jesus De Miguel Rodriguez works as a controller in the financial department at French automaker PSA Peugeot Citroen. He has a degree in mechanical engineering from the Centro Politecnico Superior de Zaragoza in Spain and an MS in economics and corporate management from the IFP School.