Here is shape of restoration, rehabilitation for Iraq oil

IRAQ'S REEMERGENCE—2

This is the second of two parts on Iraq's exploration and development history and the outlook for restoration of production and rehabilitation of facilities in the post-Saddam era.

Staged development

There would appear to be a majority legal opinion that legitimizes the reconstruction or repair of Iraq's key infrastructure under UNSCR 1483. This would include either the "restoration" of Iraq's oil facilities to its pre-war level of 2.5 million b/d and perhaps its "rehabilitation" to an original production capacity of 3.0 million b/d to 3.5 million b/d.

However, the same resolution stresses "the right of the Iraqi people to determine their own political future and control their own natural resources."

Since Iraq is under occupation and oil E&P contracts are of a long-term nature and not vital to the needs of the nation at the present time, they should be deferred until a legitimate sovereign government is democratically elected and recognized by the international community in accordance with international law.

Restoration, rehabilitation

The Ministry of Oil and its oil operating companies have had repeated experience in dealing with the reconstruction of war-torn and dilapidated oil production facilities with diligence and ingenuity, with or without the services of international engineering contractors.

Having to adjust to sharing the task with the CPA in Iraq and its counterparts in the US, a lack of law and order and acts of looting and sabotage have taken their toll in terms of the loss of time and frustration and the loss of billions of dollars in revenue resulting from loss of oil export and the cost of importation of products for local consumption.

A realistic cost estimate could only come from those on the scene who have details of the condition of the infrastructure, wells, and their productivity. Most published estimates in the past have been higher than Petrolog's. Petrolog's estimates have been based on past investment records, and it is difficult to make a comparison with other published estimates without the data to justify them.

Therefore, based on these results, with adjustments for reduced well productivity and inflation, the investment expenditure at the field's boundary per 1 million b/d expansion of production capacity should be on the order of $1.9 billion in the south and $950 million in the north, where North and South Rumaila fields in the south and Kirkuk field in the north remain to contribute the bulk of production.

Additional capital required for the repair of pipeline pumping stations and the gulf terminal is not included in the above estimates.

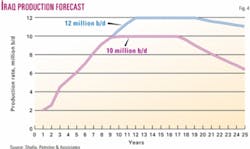

It must be emphasized at this juncture that Iraq's present proven reserves can support a production of 10 million b/d and beyond at 12 million b/d as new potential reserves are plowed in (Fig. 4).

Expanding capacity

Iraq, like the rest of the major oil producers in the Middle East, has been producing oil reserves at a depletion rate of around 1%.

The practice was inherited from the concession era, when the multinational majors had the oil reserves to produce multiples of the market demand. The companies then, however, had virtually a monopoly over the oil-integrated operations, and in order to maintain a stable crude oil price they had to adopt a low depletion rate. They also had to satisfy all their host countries and hence adopted low depletion rates in each country.

The nationalized era seems to have inherited the practice and took on itself a policy of crude oil stabilization with the aid of OPEC by regulating production. In the meantime, the multinational oil companies and their partners in the non-OPEC countries had to go into much higher depletion rates in order to enhance pay back and return on their investment, particularly, in view of investing in higher cost oil countries.

The 2001 depletion rates of the major producers were: North Sea UK 18% and Norway 8%, the Russian Federation 5%, and North America (US) 9%, Canada 11%, and Mexico 5%.

Adopting a depletion rate for Iraq of 4-5%, which is well within good reservoir management practice for large fields, would permit increasing Iraq's production rate to a peak of 10 million b/d, maintaining it for 9 years, and then allowing a natural decline. At the end of 25 years, the production rate would be 6.4 million b/d, but the reserves would have declined to 42 billion bbl from its current level.

On the same basis of maintaining a depletion rate of 4-5%, Iraq can lift the 10 million b/d plateau to 12 million b/d and maintain it for 8 years provided that 60 billion bbl additional new discoveries are added. This represents only 28% of the likely potential reserves. The plateau could be maintained for 8 years as new reserves are plowed in at the rate of 3 billion bbl/year starting in the seventh year. By the end of the 25th year, production would have reached 11 million b/d with 88 billion bbl remaining.

- With the world's annual incremental increase in consumption in the order of 1 million b/d, it would take Iraq a good many years to require a production capacity as high as 10 million b/d. As a result exploration for new potential could very well be deferred.

Clearly exploration for additional reserves is second priority to the urgently required restoration and rehabilitation priorities of the day, followed by production capacity growth at rates commensurate with market forces and Iraq's need for capital for its economic and social development.

- Under optimal conditions Iraq has sufficient pipeline carrying and export capacity (Fig. 1).

The north export system has some 3 million b/d feeding the Mediterranean, split almost equally between the Ceyhan terminal in Turkey, the Banias terminal in Syria, and the Tripoli terminal in Lebanon.

Its pipeline carrying capacity in the south is 2.8 million b/d, divided between 1.6 million b/d at Mina al-Bakr and 1.2 million b/d in Kor al-Amaya. Additionally, the pipeline system in the south can feed the Red Sea at a rate of 2.15 million b/d in Saudi Arabia to the Yanbu Terminal. At the present time, however, Saudi Arabia is out of reach and Syria's system requires rehabilitation to be brought into operation. In the medium term the pipeline and export system would not be a restrictive factor.

A strategic pipeline connects the northern and southern pipeline systems. It has a northern flow capacity (to the north) of 1.5 million b/d and a southern flow capacity (to the south) of 800,000 b/d.

Technological limitations

Iraqi experts have demonstrated high capability and competence under the severe working conditions of an authoritarian regime, sanctions, and three devastating wars.

The replacement of wells and repairing or replacing of damaged equipment and other production facilities in the old and new producing fields may not take more than 2 years in order to restore production to its pre-war level of 2.5 million b/d and to rehabilitate to presanctions levels of 3 to 3.5 million b/d, law and order permitting.

There is, however, strong evidence that the major two producing fields, Kirkuk and Rumaila, have suffered reservoir damage, which would lead to a serious loss of recovery unless remedial action is taken. It is a matter of urgency that each field requires assessment with the aid of bottomhole measurements and surface seismic surveys. The data obtained therefrom, together with past records, should allow for a diagnosis of the nature and size of damage and enable remodeling of the reservoir formation and the planning of production management techniques and procedures, in order to ensure optimal recovery.

However, it is indeed very sad that too few Iraqi experts are left in Iraq today to cope with the huge task at hand. They are a rare resource, and none should be laid off or discriminated against because of what might be their political conviction.

The authoritarian regime and long years of sanctions have also taken their toll on the training and updating of Iraqi oil experts, required to keep up with fast growing pace of technological advancements.

It is, therefore, most vital to remedy this and it is a task that should go hand in-hand with industry rehabilitation and production capacity buildup, and it is one that should not be belittled or ignored.

Long-term E&P plan

Delineation as semiexploration has limited risk and, therefore, it is logical for the national effort to prioritize the programming of the discovered but not delineated anomalies in partnership with the international companies on the basis of a suitable contractual regime whereby the partner provides the necessary capital and state-of-the-art technology.

It is helpful to recall that Iraq's proven reserves are housed in 80 fields, the bulk of which are housed in 43 fields, and that the remaining 37 have been allocated only 100 million bbl each, simply because these have not been delineated and as such were assigned only a small nominal figure.

Also, there are some 530 structural anomalies, according to semiofficial reports, but that some 440 in our estimate are sufficiently prospective to permit inclusion. Of the above, only some 115, which fall mainly outside the western desert, have been drilled to date, leaving 325 to 415 structural anomalies to explore.

Market limitations

Restoration and rehabilitation to reach a production capacity of 3 million b/d to 3.5 million b/d could be achieved by 2005, assuming return of law and order, with expansion to a production capacity of 5 to 6 million b/d perhaps by 2010. That would imply that Iraq manages to export at an annual incremental growth of around 500,000 b/d, which amounts to around 50% of the world's annual growth.

While this is possible, there are three factors to consider.

Firstly, which is a cause for optimism, the oil fields of the major oil producing countries can continue to produce at their maximum plateau well into this millennium, while other oil fields of the major oil producing regions of the rest of the world would have peaked. The consuming countries, especially from the major consuming areas of Asia, the Far East, and the US, would become more dependent on Middle East oil. Meanwhile, the cost to these countries and especially to Iraq remains low, which in other producing countries would rise due to the requirement for secondary and tertiary recovery and the search into deeper horizons.

Secondly, again a cause of optimism, geopolitics is likely to change in the medium term in favor of the Middle East and particularly Iraq. This implies that dependence on Russian oil and the expensive Caspian Sea would be reduced.

Thirdly, an optimistic or pessimistic note depending on OPEC's future policy, OPEC, the swing producer, has lost considerably its market share to non-OPEC producers. With continued market loss or stagnation, OPEC must rethink its strategy. No doubt, OPEC has served profoundly its members and world oil market stabilization, but non-OPEC members should also be made to recognize the cost of lower prices to their budgets, as well as the threat of closure of high cost oil areas and regions.

On the other hand, OAPEC, as a family of Arab and neighboring nations, should seriously consider accommodating Iraq, which has lost sizable markets and whose people have suffered considerably.

Indeed, OPEC must reconsider.

Iraq's oil resource is of the order of 330 billion bbl. It would take Iraq 300 years to exhaust its rehabilitated production of 3 million b/d, 180 years at 5 million b/d, and 90 years at 10 million b/d.

Keep in mind that the share of petroleum as an energy source is of the order of 40%, which may decline in the face of competition from other sources (hydrogen cell in the main) and for environmental reasons, and that the petroleum era is estimated to last some 40 to 50 years.

Finance limitations

Future expansion derived from the main fields (Rumaila North and South and Kirkuk), in almost equal increments at the field's boundary, should be on the order of $1.9 billion/1 million b/d and $950 million/1 million b/d in the North.

Grassroots production capacity of other discovered fields, with well productivity in the region of 1,500 to 2,500 b/d/well, would cost $3-4 billion/1 million b/d, and it should not exceed $5 billion/1 million b/d. There are, however, semiofficial reports that place the capital investment cost at $5-6 billion/1 million b/d.

An investment cost by the national oil company of the order of $5,000/ daily bbl would be recovered in 7 months of production at a price of $24/bbl.

Under normal conditions, the necessary capital could be borrowed from financial institutions. Production capacity would be built in stages in such a way that the capital inflow pays for the investment and original debt along a predetermined time scale.

It must be fairly feasible to have an Iraqi national oil company, organized in the future on a commercial basis, with authority to obtain loans. The oil industry elsewhere has been built on some 80-90% loan basis, and there is no reason for Iraq's industry not to consider as one way to proceed.

An alternative is for the national oil company to enter into a contractual regime with the international oil companies to expedite the process of rehabilitation and future production capacity expansion instead of paying out cash payments to service companies.

Such arrangements would provide the state-of-the-art technology, training, and investment capital. Such arrangements could take the form of buyback service or production sharing contracts and, if needed, with, perhaps, the added incentive of a future exploration contract on a production sharing basis.

The logical approach is to have a balanced combination of both as circumstances dictate.

You will note that I have excluded privatization as a means to raise capital or provide benefits, for the following reasons:

- Privatization of the upstream oil industry, whether partially or 100%, is equated today with denationalization. Iraq's economy is almost totally dependent on its oil export income. With decisionmaking for exploration, production, and exports in the hands of multinationals, Iraq's economy and its government's decisions would be at the mercy of the multinationals, whose interests naturally are firstly to their shareholders.

This would the case in addition to the numerous disadvantages of the kind discussed above, mainly possible incompatibility with the national interest under future conditions and the potential use of their power to slow activities or to switch supply to other countries when it best serves their interests.

- No particular advantage is gained by way of investment capital, technology, or efficiency that cannot be obtained from other contractual arrangements.

- Decisions made over a resource system depend not only on economic or technological criteria but also on political, historical, and cultural considerations, in addition to the characteristics of the deposits and their environment.

- Finally, denationalization runs against the grain of almost every Iraqi; this is a significant consideration in any future democratic Iraq.

Guiding policy

Here is a set of suggested guiding principles:

The national oil industry should be given a pivotal role to play without, however, excluding a positive role for the international oil companies, with the right balance, at the right time, and under the right contractual arrangements, and laws and regulations.

- Iraq's interests would be better served by separating the Ministry of Oil from the national operating companies. The ministry could then focus on policymaking and have a supervisory role over resource management and the negotiating and issuing of licenses.

- The national oil company should form the state pivotal enterprise, whose function is to implement government policy for exploration and production, in order to accomplish predetermined objectives. It should be established as an independent commercial company in accordance with prevailing laws and regulations.

It should have sufficient capital and the right to borrow and enter into joint ventures or associations with others in accordance with approved contractual regimes. Its board should be appointed by the government and from among leading experts in oil, finance and related skills. Above all, it should be so organized as to ensure efficiency, transparency, and accountability.

Clearly, the restoration and rehabilitation of the oil industry should take priority. In the mean time, a process of evaluation and reassessment of the petroleum resource and its management should be started urgently. Setting priorities is vital. This may need to begin with attitudinal change so that consultation and consensus are encouraged as the means to arrive at optimal oil policy, planning, and organization.

Production capacity expansion and growth should be based on a composite master plan that takes into consideration the country's development and economic needs. It should be based on the optimal use of the proven reserves housed in numerous locations, with an alternative option to cater for future additional potential reserves.

Market capacity, investment capital and the capacity and role of each of the national oil companies, and the complimentary role of the international oil companies, as well as administrative, legislative, and regulatory needs should be simultaneously assessed and integrated in the plan.

Petroleum law should state, amongst other matters that:

1. Petroleum resources are the property of the state and should be managed in the best interests of the nation, in accordance with a legislative and regulatory system capable of making open and transparent decisions.

2. The preservation of the petroleum resource and environment be upheld and accordingly gas flaring should be stopped (in stages) in order to preserve gas and to protect the environment.

3. The Ministry of Oil should ensure that exploration, development, and exploitation operations be efficient and in accordance with the best good oil industry practices.

Reference

1."Oil Production in the Gulf Vol. IV," study by Petrolog & Associates and Centre for Global Energy Studies, 1997.

The author

Tariq Ehsan Shafiq (tshafiq4 @aol.com) has worked in the oil and gas industry worldwide in various capacities for 50 years and as a petroleum consultant for more than 30 years. The latter role has involved examining upstream oil production policy, evaluating and negotiating petroleum agreements, and carrying out technical and economic feasibility studies on oil and gas discoveries, refineries, and pipelines for private and government major clients. These included Petromin and the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Oil, the Libyan National Oil Co., National Petroleum Corp. of Jordan, the Libyan Ministry of Industry, Esso, Petrol Rico, and C. Itoh, Toyo Engineering, and Marubeni of Japan.

In Iraq, he was a founder and director of Iraq National Oil Co., of which he served as vice-chairman and executive director in 1964-67. Before this, he served 10 years with Iraq Petroleum Co. in various technical capacities in Iraq and London in 1954-64, including as head of petroleum engineering in 1963-64. He also worked with M.W. Kellogg Corp. on construction of the Dora refinery in 1953-54. He has a BS in petroleum engineering from the University of California-Berkeley and an honorary masters degree from Oxford University.