Study finds petchem cash margins out of sync with capex decisions

Petrochemical Prospects

Recent research confirms no correlation exists between cash margins and decisions of a large chemical producer to invest in a new plant; specific corporate priorities rather than a "trigger" point mechanism determine the timing.

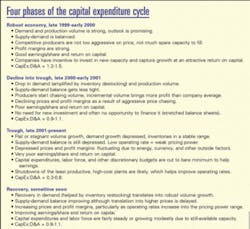

A popular theory, often asserted by chemical consultants, assumes that a decision to build a new commodity chemical plant is triggered when cash profit margins reach a so-called "reinvestment economics level."

Corporate management and boards theoretically spring into action once returns exceed the cost-of-capital benchmark. Everyone must be watching for that moment, therefore, that will signal the beginning of a new investment cycle.

The theory sounds fairly logical: One would decide to spend money after earning enough of it. Our research shows that this theory does not work.

This theory does not explain the capital-investment cycles of the major petrochemical producers: major oil companies, major US chemical companies, and participants in the largest Middle East and China projects. In fact, it is difficult to find chemical companies for which this theory does work—only small private chemical companies, clearly a minority in today's new capital investment market.

Reinvestment economics

In the typical consultant's chart there is a threshold typically corresponding to a 10% after-tax return on capital, after which presumably chemical producers decide to invest capital in construction of new plants.

Presumably it is therefore important to identify such point, if it does indeed help predict the beginning of a new investment cycle, which in turn will lead to overcapacity and decline in chemical profitability cycle.

We analyzed data for the past 10 years focusing on many chemical producers, which include most active companies in current and future chemical production: major oil companies, major US chemical companies, and state and private participants in the largest new projects in the Middle East and China.

If the traditional theory holds true, the timing of new capital investments should correlate with peak cash profit margins, a typical measure of profitability in asset-intensive commodity chemicals. Due to the need for environmental permits and other approvals, a large capital-expenditure investment typically lags a company decision by a year.

Although most companies in our study are large, global chemical producers, there is still a large difference in scale. ExxonMobil Chemical Co., for example, is 3-5 times larger than ChevronTexaco Corp.'s or Occidental Petroleum Corp.'s chemical divisions.

To make the comparisons across all companies easier, we used the ratio of capital expenditures to depreciation and amortization (CapEx:D&A) as a measure of new capital investment relative to the size of existing assets.

Petrochemical assets are often depreciated on 20 year, straight-line basis with a required maintenance investment of about 0.8 times the D&A. We consider that capital expenditures in excess of 0.8 times the D&A are needed for business expansion purposes. This is a rather crude rule of thumb because the actual ratios for a given company might vary, but it should help the analysis of major investment trends.

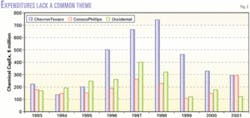

Table 1 clearly shows the absence of a common prevailing trend. Chemical investments seem to be driven by company specific, long-term corporate plans, rather than by the "trigger points" of the chemical profitability cycle.

In the late 1990s, well after the petrochemical profitability peak in 1995, some large integrated oil companies invested in their global chemical operations (Fig. 1).

They built large integrated complexes mostly outside the US: ExxonMobil and Shell Chemicals Ltd. in Singapore, ExxonMobil and Chevron in the Middle East, and BP PLC in Southeast Asia.

In contrast, Phillips Petroleum Co. (now ConocoPhillips) and Occidental maintained low and steady chemical investments (Fig. 2), roughly in line with depreciation.

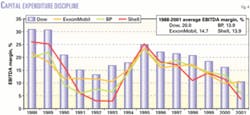

Ethylene plus polyethylene profits may be too crude a proxy for the chemical cycle for a large, diversified chemical portfolio. We also analyzed, therefore, the companies' reported earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) margin for 1988-2001. The EBITDA margin is a good proxy for cash margins.

The profit profile is slightly different for each company; however, the peaks (1988-89 and 1995) and troughs (1991-93 and the current) are clearly common for all major chemical producers.

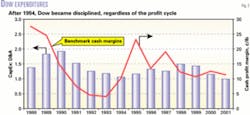

Higher profitability does not necessarily lead to higher chemical investments. For example, Dow Chemical Co. showed the highest cycle-average EBITDA margin, yet the company has held chemical investments at a fairly steady low level since 1994 due to a new capital investment discipline (Figs. 3 and 4).

To explain the lack of common trend, we compiled a comparative analysis of eight major groups in commodity chemicals (Table 2).

We ranked companies based on common features: size of current and future expansions, and vertical and horizontal diversification.

The companies do not make decisions to invest in new chemical projects in isolation from other factors, such as alternative investment projects, sources of financing, and expected returns.

Table 2 shows that only small public and private companies could potentially follow the reinvestment trigger rule because they rely on public debt and equity markets to finance large new projects.

Those companies, however, represent only a small share of total ethylene production, and a small share of new announced ethylene projects; they will play a much smaller role in the next decade.

The more ambitious companies with the largest new capacity additions (Middle East and China) will have a much more significant impact because they will account for more than 60% of new ethylene capacity in 2002-07.

Different factors, trigger economics not being one of those, will decide the timing of those start-ups.

China joint-venture projects have proven to be notoriously difficult to negotiate.

Those projects were initially targeted for 2001 start-ups but were delayed to 2005-06.

Middle East projects are easily financed due to the attractive economic returns that are based on inexpensive local ethane.

Local politics, therefore, is the primary factor in those decisions, and cyclical profitability has little to do with the decision's timing.

There are large differences in the investment factors among key players (see accompanying box). It is no surprise that consultants fail to identify a single common factor for investment decisions for the global chemical producers.

The alternative to a common "rule of thumb" is a systematic collection and analysis of all current and expected projects, considering raw materials costs, nature of project participants, location, and financing terms.

The authors

Sergey Vasnetsov ([email protected]) is a senior research analyst at Lehman Bros. Inc., New York City, with responsibility for covering the major US chemical companies. His experience includes 11 years of chemical research, both in academic and applied industrial areas. For the past 7 years, his research has focused on key fundamental drivers that shape the global chemical industry. Vasnetsov holds an MSc in chemistry from Novosibirsk University, Russia, and an MBA in finance from Rutgers University, Newark.

Zoya Kovenya is a graduate student at New York University, pursuing a PhD in economics. Her current research interests include regional trade and competitiveness, outsourcing trends, and the impact of energy and currency fluctuations on energy-consuming industries. She holds an MSc in economics from the College of Economics, Moscow, and a BSc in mathematics from Novosibirsk University, Russia.