Iraq oil development policy options: In search of balance

IRAQ'S REEMERGENCE—1

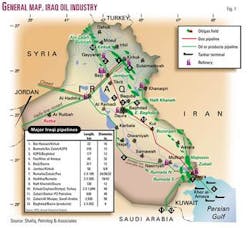

Iraq may prove to have one of the world's greatest endowed petroleum resource bases, with oil potential reserves in excess of 215 billion bbl and ultimate proved reserves of around 140 billion bbl of oil. Moreover, its finding and development costs are low, among the lowest in the Middle East (Fig. 1).

However, its historical maximum production rate in any year has not exceeded 3.5 million b/d, although its exploration and development history has stretched over eight decades.

The traditional slow-go approach of Iraq Petroleum Co. (IPC) and associated companies, their ability to shift their activities where it best served their interests and to strengthen their negotiating power, together with Iraq's politically driven decisionmaking and confrontational policy, as well as years of sanctions and unnecessary and destructive wars, have proven to be serious impediments to the development of Iraq's oil industry.

Today, its production facilities are either dilapidated or war-torn to the extent that last September its production rate sank to around 1 million b/d from a pre-war level of some 2.5 million b/d.

Hence, production capacity restoration to 2.5 million b/d and rehabilitation to 3.5 million b/d are the priority of the day.

Down the road, however, future exploration and capacity expansion require much time and homework in order to prepare a hydrocarbon law and the administrative and managerial organization that can cope with an accelerated production capacity expansion. This expansion would only be limited by market conditions and consumers' outlook, as Iraq's present proven reserves, as shown in this two-part article, can support a production rate of 10 million b/d.

The reserves are so fundamental to future planning that for this reason a review of past estimates was carried out. The results confirm the credibility of the figures cited here. The finding costs estimated for the three main areas ranged from 0.1¢/bbl in the south to 5.6¢/bbl in the northwest and 0.4¢/bbl in the northeast with a volumetric average of 0.26¢/bbl. Development costs ranged from $750/daily bbl in Kirkuk and surrounding areas to $1,570/daily bbl in the south and around Zubair and Rumaila, and $3,130/daily bbl for the smaller fields in the northwest, with an average of $1,040/daily bbl.

An examination was then carried out of the achievements, merits, de-merits, and impediments in each regime during the concessions and national exploration and development eras.

The scene was then set in order to be able to plan and cost the restoration phase to a pre-war level of 2.5 million b/d and the rehabilitation phase of producing fields to the pre-Gulf war and sanctions level of 3.5 million b/d, and finally, to consider the guiding policy and plans required in order to proceed with efficiency, transparency, and accountability taking into consideration the changes needed by way of administration and management organizations and capital and technical requirements.

Reserves and costs

Much has been published and debated in oil conferences and publications about Iraq's oil reserves, but little evidence has been given to back up the credibility of either a present proven reserve figure for Iraq of some 112 billion bbl, and particularly its additional future potential of 215 billion bbl, or its low finding and development costs.

This has given rise to speculation that the figures may be exaggerated from some quarters and cynicism from others.

Hence, since the size of oil reserves and their finding and development costs are so fundamental to the conclusions and guiding policy and plans advanced in this article, here is some detail to establish their credibility.

Proved and potential reserves

In 1966, Iraq National Oil Co. (INOC) carried out a study of potential oil reserves covering 215,000 sq km south of the horizontal line at the center of the country and to the south, but excluding the major producing fields Rumaila and Zubair. The information and data were derived from the records of IPC and its associated companies BPC in the south and MPC in the northwest.

A total of 301 anomalies were identified, mainly by gravity and some seismic surveys. Of these, only 135 anomalies were considered sufficiently credible. Aided by their geological settings and by probability analysis, the oil in place of the Tertiary and Cretaceous ages was estimated at 350 billion bbl and potential recoverable oil reserves at 111 billion bbl.

In 1994, the author presented a paper at a geological oil conference in Amman, Jordan, and developed it further a few years later for an oil conference at the Centre for Global Energy Studies (CGES) in London. It was based on an empirical relationship that relates the discovered oil in a geological basin to the exploration effort along a time scale.

It demonstrates that exploration effectiveness starts low at the initial phase, then picks up sharply and grows almost linearly until the bulk of the reserves are discovered, when it slows down as the ultimate reserves of the basin are reached.

In Iraq are some 530 structural anomalies that have been identified by geophysical means. Of these, only 114 have been drilled and, by 1994, oil was established in 73 structural anomalies.

I estimated the total ultimate oil reserves housed in these 73 enclosures to be in the order of 144 billion bbl, which is in conformity with published data and the experience of Iraqi experts.

With the use of size distribution and varying success ratios, the potential oil reserve was estimated to be in the order of 280 billion bbl to 360 billion bbl housed in 143 to 183 structural anomalies.

In a further joint study with CGES on Iraq published in 1997,1 the Petrolog & Associates team including myself and others among the most experienced petroleum engineers and geologists carried out an extensive analysis of Iraq's exploration potential, taking over 3 man-years.

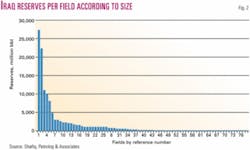

The proven ultimate oil reserves were estimated at 128 billion bbl, housed in 80 fields (Fig. 2), of which 124 billion bbl were housed in 43 discovered fields. The balance, 37 fields, have been discovered but not sufficiently delineated and were assigned only 100 million bbl each.

Iraq's potential reserves were estimated conservatively to be in excess of 216 billion bbl. These are large fields with as much reserves as in some of the discovered fields. The largest eight fields housed some 50 billion bbl, compared with 92 billion bbl housed in eight discovered fields.

Our estimate was based on conservative volumetric calculations, using average porosity, oil shrinkage, and a recovery factor not exceeding 31% for the oil reserves recoverable from 224 anomalies, among the total of 440 surface and subsurface identified anomalies sufficiently prospected to be included.

The potential proven reserve was estimated at 455 billion bbl, to which a success rate of 47.5% was applied (being the average of 70% terminating at 25% at the end of the exploration period), giving 216 billion bbl of proven reserves.

On the basis of the above results, we endorse estimates of an ultimate proven reserve of 140 billion bbl and a potential reserve of 215 billion bbl, as reported here.

Finding and other costs

In the joint 1997 study, past accounting records for IPC and associated companies were examined and tangible and intangible assets were analyzed and adjusted for inflation in order to reflect current costs at date of publication.

Finding cost. The average finding (exploration) cost for Iraq amounted to 0.26¢/bbl. IPC, BPC, and MPC revealed different costs for their respective concession areas.

The BPC area in the south had the lowest finding cost of 0.1¢/bbl, followed by a cost in the north to the east of the Tigris river of 0.4¢/bbl and northwest of the Tigris 5.6¢/bbl.

Clearly these costs reflect the relative richness of their respective areas and not different management or technical skills as the three companies shared a common management and shareholders.

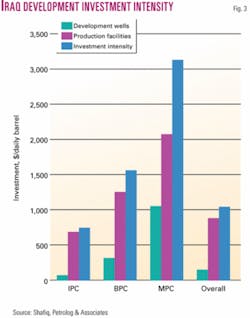

Development cost. The two major cost components, production facilities and wells, were assessed and the average development cost at the field boundary was derived.

Our assessments revealed that Iraq's overall average Development Investment Intensity (cost per a rate of 1 b/d) in the different areas amounted to an average of $1,040/daily bbl, which is made up of $750/daily bbl (IPC), $1,570/daily bbl (BPC) and $3,130 daily bbl (MPC) at the field boundary (Fig. 3).

It should be mentioned at this juncture that the future development cost will change to reflect lower well productivity, restricted natural water drive requiring full water injection, deeper wells, and in some areas more difficult drilling conditions and generally smaller fields to develop.

However, costs will remain at the cost level of Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. On the whole the finding cost should remain in the range of a few cents per barrel and the development cost around $5,000/daily bbl.

Lessons from history

History is there for the wise to consider, build and improve on, to consider the successes and avoid its failures.

This short review of Iraq's oil industry during the concession and nationalized eras highlights the impediments to its exploration and development.

Concession era

IPC acquired its first concession agreement over a limited area in 1925 and extended it in 1930 (MPC) and then in 1938 (BPC) to cover practically all of the country for 75 years, without relinquishment.

The concession agreements' history, however, goes back to World War I, when a victorious Britain took over concession rights in Iraq.

A significant point to note here is that while the First World War was not triggered by the struggle for oil, the victorious parties found oil concessions to be a valuable prize. And in a similar way, the gulf wars seem to have signaled the return to the Middle East of the multinational oil companies.

Long term exploration and production (E&P) agreements must be written and applied in good faith. The presence of the participation clause in the IPC agreement was so worded as to make it inapplicable. Participation was conditional on the IPC parents companies' issuing new shares, and since the IPC is a private company, no new shares might ever be issued if they so wished, as was indeed the case.

The participation clause became a major source of dissatisfaction and long disputes.

Agreements between the state and foreign oil companies need to be balanced and fair in order to reduce potential disputes and to be able to stand the test of time and, preferably, to permit reviews in the light of justifying changed circumstances.

The Revolutionary Government of 1958 could not accept the de facto powers of the companies. They made demands in connection with relinquishment and participation, which were not acceptable by the multinational IPC parent companies. To accept these demands they would have to pass them on to the rest of their concessions in Middle East.

They decided that freezing their activities in Iraq or losing their concession rights would be preferable to accepting Iraq's demands. Not only did exploration cease, but the multinationals used their power to switch supply to other areas, leaving little growth if any to Iraq.

As a result, Iraq legislated Law 80 in 1961, relinquishing unilaterally 99.5% of the concession areas, and worse including part of Rumaila field and all the discovered but undeveloped fields. In so doing the government ignored the realities of the oil industry's concession terms.

Law 80 became the cornerstone of Iraq's oil strategy to such an extent that, although the 1965 negotiations produced agreement terms that met the demands of the 1960 negotiations and improved on them, the politicians of the day thought otherwise. Political considerations and ideology took over economic realities, and Iraq pursued its confrontational policy with oil companies singly until 1972, when it nationalized the oil industry in phases over 2 years.

In so doing, Iraq was denied economic benefits acquired by the other OPEC members throughout these years and suffered a loss of production, capacity growth, and significant income and markets throughout the years 1961 to 1972.

The lesson is clear: Political decisions at the expense of economic reality can be very costly to the nation, indeed.

The IPC parent companies did not have the same interests in developing Iraq's oil industry. BP had greater interests in Iran and Kuwait, while Exxon's interests lay in Saudi Arabia. France's CFP was crude deficit, and Iraq was its sole source in the Middle East. As a result there was a lack of conformity of interest, which contributed to slow exploration and development.

The nationalized era

IPC and its associated companies developed the oil industry in Iraq over some five decades on the basis of sound technical and commercial principles and produced a generation of Iraqi oil experts and technocrats.

INOC took over seven producing fields, with a total production capacity of around 1.5 million b/d, and a host of discoveries.

INOC, established in 1964, did not begin operating until the early 1970s. It expanded exploration and development fairly swiftly. The 1970s witnessed a production capacity reaching 3.5 million b/d and the highest reserve growth in the world as the annual rate reached above 6 billion bbl, equivalent to the total growth rate in the rest of the world.

Prospective and proven formations, above and below the main producing formation, were tested in producing and discovered fields and delineated new structures. Some 40 prospective formations were logged. A number of these had been logged by the IPC and associated companies but were left insufficiently tested or neglected as long as they tested only a few thousand barrels a day.

The exploration drilling intensity increased from 1.5 wells/year during the concession era to 3 wells/year, while the overall success rate was maintained at 3 out of 4 wells. The total drilling intensity amounted to 10 wells/year in the 1960s, compared with 36 wells/ year in the 1970s and 92 wells/year in the 1980s during the years of the nationalized era.

In 1989, the nationalized oil industry drilled 178 wells and over 1 million ft of hole.

Clearly the nationalized oil industry demonstrated a high degree of success. Its engineers demonstrated ingenuity in making good what their authoritarian politicians allowed to be damaged or ruined in the three destructive wars. Their plans and performance were not only to achieve a target income but also to develop the most valuable assets in the country, as seen in their search to explore and test every oil potential formation vertically and horizontally.

Impediments to E&D

However, political decisions contributed to the impediments against progress and caused a substantial loss of income.

Iraq's politicians resorted to a confrontational strategy with the companies during the 1960s, when an alternative was available. Instead, Iraq could have achieved the same results with patience and better planning, through negotiations rather than legislation, and by working within OPEC rather than acting singly outside it.

The Iraqi regime also failed to develop oil institutions capable of running a modern oil industry with transparency and accountability. Scientific research was neglected. Staff changes were carried out for political reasons and were too frequent to permit continuity. Training was badly neglected.

Further, the former Iraqi regime's authoritarian and arrogant policies of the last three decades plunged Iraq into three unnecessary and devastating wars and savage sanctions. The wars consumed time and resources on repairs and reconstruction, and the sanctions contributed to maintaining already out-of-date reservoir management practices.

In addition, the absence of any separation between ministerial policy roles and the national oil company's operational and commercial functions only contributed to less transparency and accountability.

Next: The likely shape of restoration and rehabilitation of Iraq.