FERC Hackberry decision will spur more US LNG terminal development

A significant shift in US regulatory policy has occurred as a result of the US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission's decision late last year to allow US LNG import terminals to operate without complying with open-access requirements and to charge market-based rates.

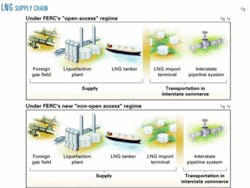

In its "Preliminary Determination on Non-Environmental Issues relating to the Hackberry LNG Terminal, L.L.C." ("Hackberry Decision"), the FERC acknowledged that LNG import terminals are actually the end point of the LNG supply chain, not the starting point of the US interstate transportation infrastructure (Fig. 1).

The new "nonopen access" policy should encourage development of new LNG import terminals in the US, and thereby provide alternative sources of supply, promote market competition, and reduce prices and price volatility.

After more than a decade of deregulation during which open-access requirements were strictly applied by the FERC to almost every link in the natural gas transmission chain, including LNG import terminals, the commission's fears that industry participants may seek creative ways to circumvent the FERC's open-access requirements have substantially abated.

Now, the process of deregulating the natural gas industry has reached maturity, and open access to the nation's interstate transmission infrastructure is widely accepted among industry participants. What seems clear from the FERC's Hackberry decision in December 2002 is the FERC's recognition that times have changed. Whereas the process of deregulation once required strict enforcement, the FERC now seems willing to review proposed proprietary facilities on a case-by-case basis.

Background

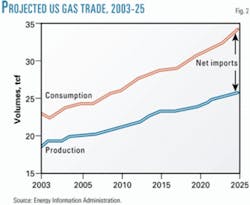

Natural gas has become the fuel of choice for new US electricity generation and is quickly replacing oil as the primary fuel for heating purposes. Over the next 2 decades, natural gas will be the fastest growing component of the world's energy consumption, but there is increasing awareness that the dwindling domestic supply of natural gas from traditional Midcontinent fields cannot keep up with this growing demand (Fig. 2).

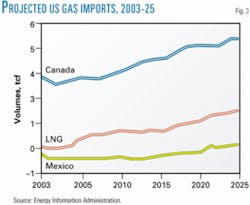

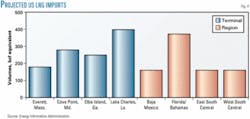

The potential growth of the market for natural gas has focused serious attention on increasing natural gas supply from all available sources, including imports from Canada, Mexico, and elsewhere, the latter supply coming in the form of LNG (Fig. 3).

Until recently, two chief factors limited continued development of an infrastructure necessary to allow LNG to be efficiently marketed in the US.

First, the economic environment has not supported a substantial increase in natural gas imports for almost 20 years. As natural gas prices have generally moved higher in recent years, however, LNG project developers have once again begun to propose development of LNG import terminals in the US.

Second, the FERC's open-access policy requirement for LNG import terminals had created substantial risk for LNG project developers. This policy required LNG project developers to offer capacity in their LNG import terminals through an open-season process without favoring affiliates.

Compliance with this policy created tremendous uncertainty for LNG project developers. After spending large sums to acquire supply and develop LNG facilities upstream of the import facility, the developer was unable to ensure capacity to land the LNG in the US, due to the strictures of the open-access policy. This limitation took needed certainty away from developers looking to complete the costly LNG supply chain, thus effectively limiting the capital expenditure commitments necessary to develop new LNG markets.

With project development costs in the billions of dollars, the risks created by the FERC's open-access regime limited development of new LNG supplies to serve the growing US natural gas market.

After hearing of this concern in private meetings with LNG producers and in a public conference, the FERC on Dec. 18, 2002, adopted a new "nonopen access" policy with respect to LNG import terminals. This new policy allows LNG suppliers to:

- Exclusively use, whether by itself or through an affiliate, the entire capacity of an LNG import terminal, if necessary, without complying with open-access requirements.

- Charge market-based rates for LNG terminaling services.

In the Hackberry decision, the commission reasoned that LNG import terminals should not be subject to an open-access policy nor required to maintain cost-based tariff and rate schedules relating to their terminaling services.

This critical change in LNG facility permitting policy may well prove to be the salvation for the US natural gas market.

Development of open-access policy

The FERC's open-access policy developed out of deregulation of the US natural gas industry beginning in the late 1970s. Under the former regulated environment, an interstate pipeline company provided "bundled services" to a local distribution company's customers.

The pipeline would purchase natural gas from producers and transport such supply to the city gate where an LDC would purchase the gas at a "bundled" price that reflected the sale, transportation, and balancing of the gas supply. Pipelines were considered to be providing merchant services, rather than operating as a mere transportation system between buyers and sellers.

Throughout the 1970s, natural gas shortages severely disrupted the US and led to a growing belief that a permanent depletion of natural gas resources was imminent. As a result, the federal government began to deregulate the natural gas industry as participants in the natural gas industry aggressively sought out alternative gas supplies, including LNG imports.

In 1978, Congress passed the National Energy Act, which included the Natural Gas Policy Act. NGPA created certain price categories that effectively stimulated domestic production and increased the supply of natural gas. Conservation efforts resulting from the nation's concern over natural gas shortages influenced consumers to curtail their use of natural gas and decreased demand.

By the early 1980s, an unexpected surplus of natural gas emerged and prices fell dramatically.

During the period of perceived shortages, many pipelines and LDCs had entered into long-term "take-or-pay" contracts with producers in order to ensure a steady supply of natural gas for utilities and other needs, while also ensuring a steady cash flow to producers for agreeing to dedicate their reserves to the pipelines and LDCs.

When prices fell, many pipelines and LDCs realized that continuing to purchase gas at higher prices under these long-term contracts was uneconomical. In the early 1980s, the FERC came to the rescue of the LDCs, allowing them to purchase gas at the prevailing lower market prices despite their long-term contracts with pipelines.

In an effort to provide some relief to pipelines, the FERC issued Order 319 in 1983 that allowed pipelines to transport gas for industrial consumers and other users, in addition to distributors. Many pipelines, however, continued to force distributors to purchase gas under the long-term contracts.

In response, the FERC issued Order 380 in May 1984, eliminating "minimum bill" requirements in gas-purchase contracts. LDCs were freed thereby to purchase lower-priced gas on the spot markets without complying with the minimum-take requirements under their higher-priced supply contracts with pipelines.

Pipelines, however, remained locked into long-term take-or-pay contracts with producers at higher prices. From the pipelines' perspective, they were required to purchase high-priced gas under long-term contracts even though they would be unable to sell the gas to their customers because of Order 380.

The FERC attempted to remedy the take-or-pay problems, while also pursuing its ultimate goal of making the transportation of gas a separate business function, by issuing:

- Order 436 in 1985, which required pipelines to provide gas transportation services on an open-access and nondiscriminatory basis.

- Order 500 in 1987, which attempted to deal with the take-or-pay problem by allowing pipelines to credit transportation services against former take-or-pay liabilities with a given producer.

In 1992, the ultimate solution came in the issuance of FERC Order 636, which completed the "unbundling" of the "bundled" pipeline merchant service.

Order 636 allowed for each of the transportation, gathering, balancing, and storage services to be contracted on a market basis. Furthermore, Order 636 required interstate pipelines to provide transportation services in an open access and nondiscriminatory manner.

The intention was to eliminate the "middle man" and move the nation's interstate pipeline infrastructure to service as transportation facilities only between the genuine market participants (i.e., buyers and sellers).

Open access applied to LNG terminals

The FERC's open-access policy became applicable to LNG import terminals as a natural consequence of development of three of the four US LNG import terminals. Each of the Cove Point, Md., Elba Island, Ga., and Lake Charles, La., import terminals were developed and built by interstate pipeline companies, albeit prior to adoption of the open-access regime.

During development of each of these projects, applications were filed with FERC's predecessor, the Federal Power Commission, stating that these facilities would be employed in the interstate transportation of natural gas. Consequently, these LNG import terminals came to be regulated in the same manner as interstate pipelines.

When the FERC adopted its open-access policies, through Orders 436, 500, and 636, these LNG import terminals fell within the scope of such policies by virtue of their status as interstate transportation facilities. Thus, the LNG import terminal was viewed as the beginning link of the interstate transportation supply chain.

The Everett Marine Terminal in Massachusetts enjoys a different history. When Distrigas of Massachusetts Corp. filed its application to construct the Everett facility, the company took the position that its proposed LNG import terminal would not be engaged in interstate commerce (i.e., by transporting natural gas across state lines) but would instead be engaged in foreign commerce as the last link in the LNG supply chain.

As the proposed facility would not be involved in the interstate transmission of natural gas, Distrigas argued, the facility should not be subject to Section 7 and Section 4 of the Natural Gas Act. Section 7 of the NGA gives the FERC, then the FPC, the authority to approve the development and construction of facilities to be used in the interstate transportation of natural gas. Section 4 gives the FERC the authority to regulate the rates and terms and conditions of service for those facilities.

Initially, the FPC agreed with Distrigas and did not subject its LNG import terminal to Section 7 and Section 4 jurisdiction. When Distrigas later conceded that portions of its imported LNG would be resold in interstate commerce, the FPC reversed its position because Distrigas was proposing new and increased jurisdictional sales outside the states of importation.

In US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, Distrigas challenged the FPC's new position over whether the FPC's Section 7 and Section 4 jurisdiction should apply .

The matter was ultimately resolved through a settlement agreement between Distrigas and its customers that was approved by the FPC on June 14, 1977. Distrigas submitted to Section 7 and Section 4 jurisdiction but did not submit to be regulated like an interstate pipeline. Therefore, when the FERC adopted its open-access policy, the Everett Marine Terminal did not become subject to the open-access requirements.

Despite the exemption of the terminal from complying with open-access requirements, uncertainty remained over the application of open-access requirements to LNG import terminals. On one hand, three of the four LNG import terminals are treated as facilities engaged in the interstate transportation of natural gas. Open-access requirements, therefore, should be applied because these terminals are simply the beginning of the interstate transportation system.

On the other hand, LNG import terminals are a necessary final component of the LNG supply chain. In this respect, these terminals are no different from gathering systems that aggregate domestically produced natural gas supplies for introduction into the US wholesale gas markets.

Cost-based rates

LNG import terminals have generally employed a cost-based rate calculation to determine the applicable rates for their terminaling services. Making this calculation involves aggregating its costs, including the costs of formation, construction, operation, and maintenance, and distributing them over the useful life of the terminal. To this cost basis, an additional amount is added to provide for a reasonable return of and on capital to the LNG project developer.

In this manner, the terminal's rate base is not subject to prevailing market forces because these rates are tied to the actual cost of the terminal itself, and such rate base will only increase in accordance with additional capital expenditures and decrease through depreciation of the terminal.

Because one of the goals of deregulation was to separate the transportation service from the "true" market participants, this cost-based rate structure is an efficient tool preventing transportation service providers from using the well-developed interstate transmission infrastructure in the US as market power over customers which are "captive" to its interstate transportation services.

Unless pipelines and terminals can show that they do not have market power, they are not allowed to charge market-based rates for these essential facilities. To allow pipelines and terminals with market power to do so would defeat the intent behind deregulation of the natural gas industry.

Shift from open access

The FERC's shift in policy late last year in allowing LNG import terminals to operate without compliance with open-access requirements resulted from a well-reasoned decision by the commission.

First, the FERC analyzed the actual process of introducing natural gas derived from LNG into the domestic natural gas markets. It stated that:

"The sale of natural gas from [LNG import terminals] would occur at, or downstream of, the tailgate of the LNG plant, where re-vaporized LNG would be delivered into Hackberry's pipeline. These sales of natural gas would be made in competition with other sales of natural gas produced in the Gulf Coast region in a deregulated competitive commodity market. The terminal's cost would be part of the costs of producing and delivering LNG to the Gulf Coast natural gas marketplace, and would be received only through the sales of natural gas in these or downstream markets."

In recognizing that the "true" introduction of LNG supplies into the marketplace would be at the tailgate of the LNG import terminal, the FERC was able to view the LNG supply chain as essentially being equivalent to onshore production of natural gas. Thus, the LNG supplier would simply be an "alternative producer" in FERC's eyes.

As an alternative producer, the LNG supplier is a market participant and not an interstate transmission facility that should be subject to open-access requirements.

In addition, the commission received extensive comments from industry participants in support of proprietary LNG import terminals and no comments in opposition. Significantly, the FERC noted, "Participants...argued that investors in a 'full-supply-chain' LNG project needed the assured access to terminal capacity that could not occur under open-season bidding...."

As noted, the capital investment required for LNG projects is in the billions of dollars. Foreign natural gas producers financially capable of exporting LNG are compelled to develop the entire supply chain in order to ensure their ability to deliver sufficient volumes of LNG to the US.

In this scenario, LNG projects simply do not become economic alternatives to domestic natural gas supplies unless large volumes of LNG can be introduced into the market. The benefits that may be realized through these economies of scale require development of the entire supply chain to ensure capacity will be available to the LNG supplier at every link in the chain, including capacity at the LNG import terminal itself.

The FERC's open-access policy put a potential LNG supplier in the untenable position of deciding whether to fund the development of the LNG supply chain, including an LNG import terminal, only to offer up its terminal capacity to third parties through the open season process.

Therefore, even though the result was unintended, the open-access policy effectively deterred investment in new LNG infrastructure in the US.

Further, the FERC acknowledged "many foreign governments would not approve LNG export projects without clear and certain access to the markets." In most foreign countries where substantial hydrocarbon production is occurring, the host governments rely on the royalties and taxes received as a result of the export of hydrocarbons, including LNG.

These governments often place destination restrictions on producers to ensure the exportation of their native resources will yield the desired levels of royalties and taxes. Consequently, the uncertainties created by the open-access regime may have influenced such host governments to forbid exportation of LNG to the US and insist instead that their LNG be exported to more acceptable markets.

The FERC referred to the amendment to the Deepwater Port Act (i.e., the Maritime Transportation Act of 2002), which allowed offshore LNG facilities to be operated without compliance with open-access restrictions. The impetus behind the amendment was the increased concern after Sept. 11, 2001, for national security.

Congress believed that LNG facilities 30 miles offshore posed "a lower threat to coastal communities in the event of a catastrophic emergency at the facility than the current practice of locating LNG facilities onshore." The commission ultimately determined that the same policy should be applied to onshore LNG facilities because "onshore LNG facilities should be at competitive parity with offshore facilities."

Finally, the FERC's decision to allow LNG import terminals to operate without complying with open-access requirements appears to be consistent with several of the FERC's stated goals for the natural gas industry.

- The shift away from open access provides a new incentive for, or rather eliminates a disincentive to, LNG project developers to engage in the development of proprietary LNG import terminals, creating an alternative supply of natural gas. This incentive furthers the commission's goal of promoting new sources of gas supply.

- New LNG import terminals should ease congested market areas by allowing pipelines to deliver gas from more-efficiently located import terminals. This new ability will advance the commission's goal of enhancing the efficiency of the pipeline infrastructure in the US.

- Development of new proprietary LNG import terminals will enhance market competition in the natural gas industry, a long-time goal of the FERC. This increase in market competition should reduce prices to natural gas consumers and help mitigate the effects of price volatility.

Consequently, the FERC's shift in policy will not only provide much needed alternative sources of supply at a critical point in time for the national security of the US, but also will enhance the overall market conditions of the US natural gas industry (Fig. 4).

Market-based rates

Another significant shift in policy is the FERC's decision to allow LNG import terminals to charge market-based rates for terminaling services.

Under the FERC's former policy, cost-based rate structures were applied because the predominant thinking was that this structure more accurately reflected the use of pipeline and terminaling facilities in the interstate transportation of natural gas.

In the Hackberry decision, however, the FERC noted that market-based rates would be more appropriate for the new Hackberry terminal because it would be solely bearing all risks associated with bringing the LNG to market.

The former cost-plus tariff structure should not apply, therefore, because "No captive customers bear any of the costs or the cost of recovery and the recovery of fixed costs of LNG terminaling can be accomplished only through the sales of LNG at competitive prices."

Notably, several industry participants who supported the FERC's shift away from its open-access policy did not agree with the application of market-based rates to LNG import terminals. These companies argued that Hackberry would be able to exercise market power over its terminaling services, and cost-based rate protection should therefore be applied to the Hackberry terminal.

The FERC disagreed, stating that application of cost-based rate protections to LNG import terminals would essentially provide that protection to the international LNG trade, and this was not the intended effect. The goal of cost-based rate protection was to protect the US wholesale gas market from the use of essential interstate transmission infrastructure for merchant activities.

Underlying the FERC's decision is:

- A belief that LNG project developers are really providing alternative natural gas supplies.

- A laissez-faire position that LNG project developers willing solely to take the risk to develop and construct LNG import terminals should be allowed to compete in the wholesale gas marketplace at prices sufficient to recover their costs and make a profit.

The author

James Vallee is an associate at the international law firm, Jones Day, and a member of the firm's energy specialized industry practice. His practice focuses on the representation of domestic and multinational energy companies in mergers and acquisitions, project development and finance, commodity supply and transportation arrangements, mezzanine finance, e-commerce, securities, and general corporate law matters. Vallee is a member of the Energy Bar Association, the State Bar of Texas, and the Houston Bar Association. He holds a bachelors of applied arts and sciences (summa cum laude) from Lamar University, Beaumont, Tex., and a JD from Texas Tech University School of Law (cum laude).